1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Recent socio-economic and political shifts in Mongolia depict a concerning trajectory of diminishing democratic values. The once-promised democratic systеm, deeply rooted in transparency, accountability, and justice, now appears under threat. Like many emerging democracies, Mongolia confronts a multitude of challenges. Central to these challenges is the delicate balance of institutional design and its operation, with horizontal accountability emerging as a pivotal concept. This principle ensures that state institutions keep each other in check, preventing power abuses and guaranteeing operations within legal bounds.

These challenges are evident in the annual unveiling of corruption scandals involving substantial embezzlement of public funds that shake the foundation of Mongolian society. Furthermore, the country’s legal foundation has witnessed considerable changes. Since 2000, the Mongolian Constitution — the bedrock of its democratic systеm — has undergone four amendments. Remarkably, three of these changes occurred between 2019 and 2023, spearheaded by the Mongolian People’s Party and often carried out with limited public consultations. Historically, the robust constitution of Mongolia has been celebrated as a pillar of democracy in Central Asia, ensuring a balanced distribution of power among the executive, legislative, and judiciary branches. However, recent sentiments indicate growing concerns. As reported in 2023, the individuals entrusted with upholding the Constitution now appear to be undermining it (Tumurtogoo 2023). The post-2019 amendments have generally curtailed presidential authority, bolstered executive power, and imperiled the foundational balance of power across the branches. While rationalized as measures to augment state policy ownership, ensure stability, and heighten accountability within the executive branch, these changes pose risks to the power balance between the executive, legislative, and judiciary branches.

In these times of declining public trust and legal changes present the debate surrounding the role and power of the judiciary and oversight institutions in Mongolia. On one side, there are increasing concerns about institutional inefficiency and potential biases among these institutions and a push to decentralize, reduce funding, and staffing of the judiciary and oversight bodies due to waning trust. Conversely, on the other side, there are arguments that robust and well-resourced judiciary and oversight institutions are foundational for maintaining checks and balances, especially in overseeing the executive branch. Empowering these bodies is crucial not just for governance but also for restoring public trust.

As such, this paper contributes to the ongoing debate by assessing the judicial and oversight institutions’ independence, responsiveness, and capacity. In particular, the Independent Authority Against Corruption Agency was focused among the judicial bodies. In order to measure the accountability level of judiciary, its trust level, independence and impartiality, and responsiveness and timeliness will be key elements of accountability questions.

In answering the questions, the paper will rely on the review of secondary and publicly available information retrieved from media, news and public hearing testimonies published. Furthermore, the paper examines opinions from international bodies, NGOs that have closely followed the selected corruption case and the commentary and analyses of experts and scholars. Public perception survey results as well as international indices were used to provide contextual and historical information about the Judiciary and horizontal accountability.

2. Description of Corruption Scandals

In 2017, the “60 billion tugrugs (MNT)” (25 million USD) deal ahead of the presidential election was exposed when voice recordings of high-level officials’ plan to rearrange government positions for set bribery were released. In 2019, after the Speaker of Parliament M. Enkhbold was dismissed in relation to the MNT 60 billion case to sell key government offices in exchange for election financing, several ruling party members were sentenced to four-year imprisonment by the district court. However, at the appellate at Capital City Court, the decision was dismissed (Шүүхийн шийдвэрийн хураангуй 2019). An independent media source exposed the ‘SME embezzlement’ corruption scandal in 2018. The district-level courts also made decisions to prosecute affiliated officials in 2020. One former member of parliament (MP), B. Undarmaa, was sentenced to two and a half years of imprisonment but was released on the grounds of ‘poor health.’ A new scandal called ‘Coal Mafia’ arose in December 2022. These cases show that even today, there were no clear court decisions and prosecutions against the ruling party members and their affiliates involved in corruption scandals. The scale and depth of the scandal were unprecedented, allegedly reaching MNT 40 trillion (more than one billion USD) (Davaabazar 2022).

Since its beginning in February 2023, the ‘Development Bank’ case encompasses 80 defendants and 460 individual lawsuits (S. Undarmaa 2023). The state-run Development Bank of Mongolia (DBM) is grappling with a substantial bond repayment of approximately 800 million USD due by the close of 2023. Despite this, the bank has been under continuous examination for issues since its foundation in 2012, especially regarding sizable enterprises that have secured long-term project loans from the DBM over the years. Due to a recent economic downturn and overly rosy forecasts, 69 companies have reportedly lagged in their repayments. By early 2022, the DBM’s non-performing loans surged to 500 million USD. Few years ago, the government initiated a corruption probe, which led to a criminal investigation focusing on several debtors, including prominent legislators. Several politicians from the Mongolian People’s Party and one member from the opposition HUN Party were involved in the case for ‘abuse of power and money laundering’ (Adiya 2022).

The aftermath of each scandal typically sees a surge of public outrage, often culminating in mass protests and significant media scrutiny (Adiya 2022; Bayartsogt 2018; Bekmurzaev 2023; Dierkes 2022; Lkhaajav 2017). These widespread demands for accountability often go disregarded, with tangible results rarely materializing.

It should be noted that prior corruption scandals, such as the Chinggis Bond under the Democratic Party’s majority, have also occurred. However, for the sake of relevance and timeliness, this paper narrows its focus to the most prominent and publicly recognized cases from the past eight years.

3. Horizontal Accountability Trends in Mongolia

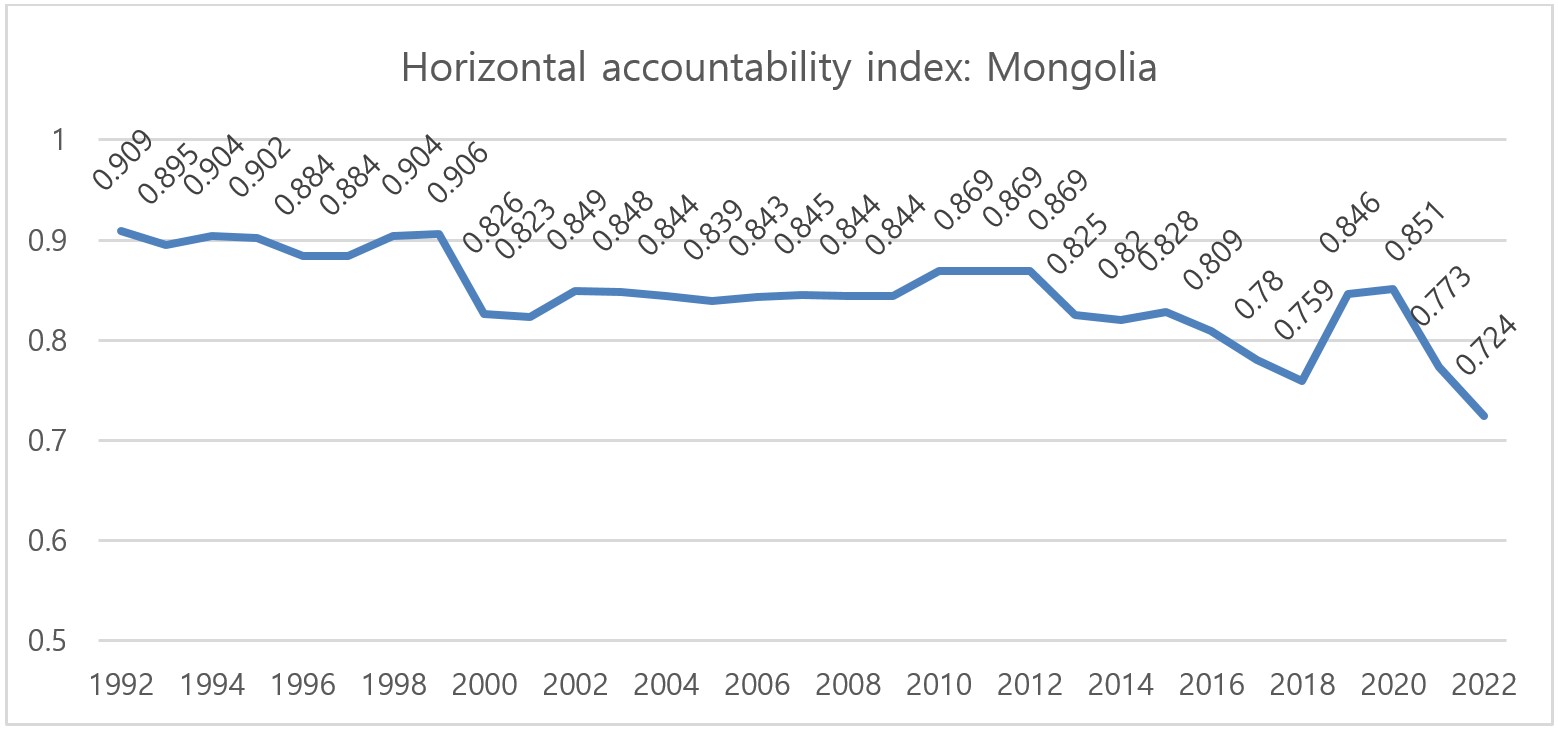

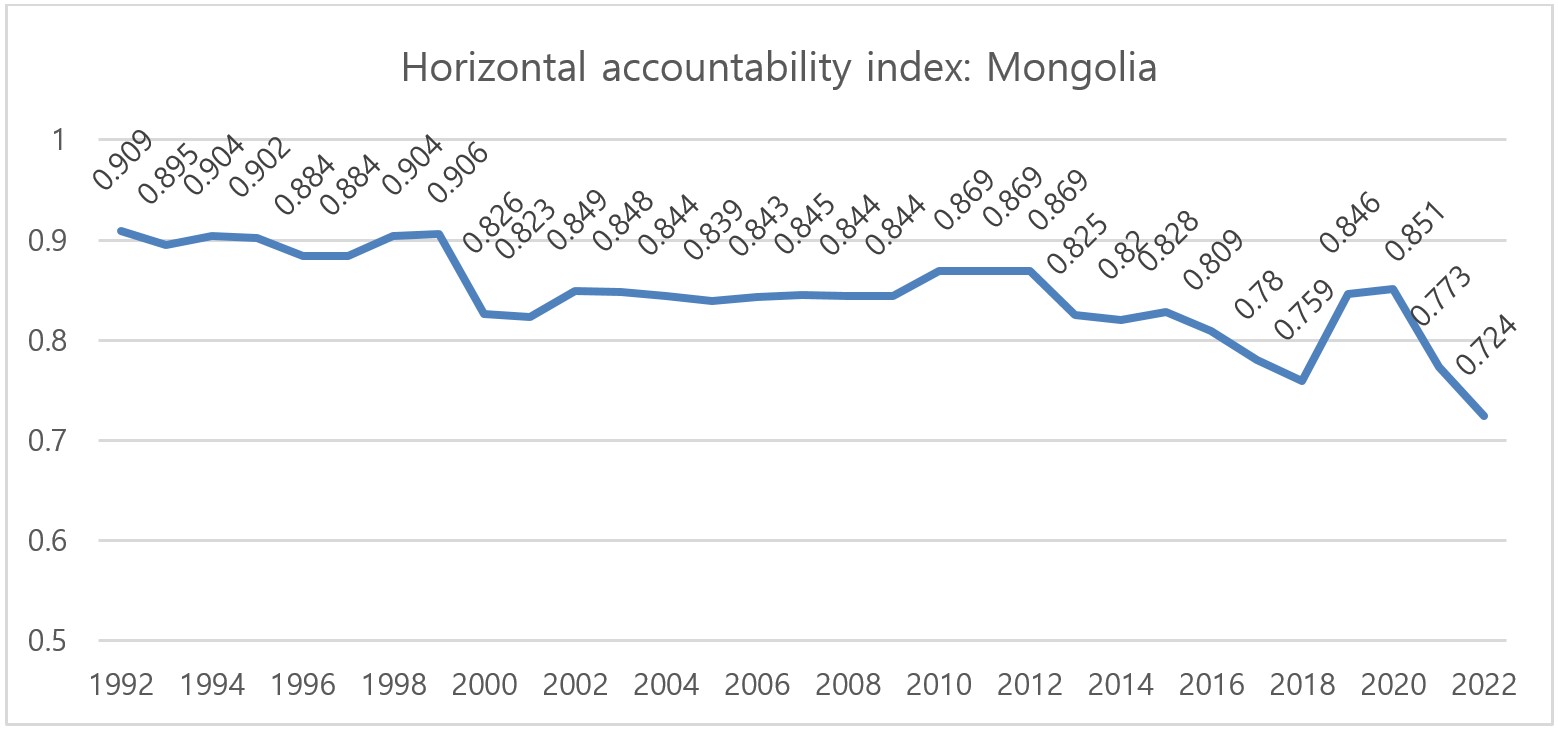

The Horizontal Accountability Index from V-Dem provides an empirical metric to measure the extent to which state entities in a country can hold one another accountable. Analyzing the data for Mongolia from 1990 to 2022 reveals interesting trends and fluctuations that offer insights into the country’s evolving governance structure and democratic practices.

Figure 1. V-Dem Horizontal Accountability Index: Mongolia 1992-2022

Source: V-Dem 2023

• Initial Surge (1990-1992): Beginning with a score of 0.686 in 1990, there is a sharp rise to 0.909 in 1992. This period corresponds with Mongolia’s shift towards democracy, and the spike suggests rapid institutional reforms aimed at introducing checks and balances.

• Stability and Marginal Fluctuations (1993-1999): Post the initial surge, the index stabilizes in the high 0.8 to low 0.9 range. This period reflects a consolidation phase, with Mongolia striving to maintain a balance of power among its state institutions.

• Decline at the Turn of the Century (2000-2005): Starting in 2000 was a noticeable dip, which reached a low of 0.839 in 2005. This downward trajectory could indicate challenges in sustaining institutional checks, possibly due to political or economic factors.

• Relative Stability with Mild Resurgence (2006-2012): The period sees the index oscillating in the mid-0.8 range with a slight rise to 0.869 by 2012, suggesting efforts to re-strengthen horizontal accountability mechanisms.

• Dips and Peaks (2013-2020): This period is marked by significant fluctuations, from a dip to 0.825 in 2013 to a resurgence in 2019-2020. Such fluctuations indicate political changes and institutional reforms impacting the balance of power.

• Recent Decline (2021-2022): A concerning decline has been observed in the last two years, with the index dropping to 0.724 in 2022, the lowest in the dataset. This drop suggests recent challenges or setbacks in ensuring horizontal accountability.

Over three decades, Mongolia’s Horizontal Accountability Index has seen notable shifts. While the 1990s reflected a promising start in institutionalizing checks and balances, subsequent years presented a mix of challenges and recoveries. The most recent decline signals a potential need for a renewed emphasis on bolstering mechanisms that ensure state entities remain accountable to one another. Analyzing whether these trends and the varying public trust in institutions central to horizontal accountability—especially in terms of how the judiciary and oversight bodies address corruption scandals—would be insightful.

3.1. Public Trust in Institutions

While public perceptions don’t directly measure the judiciary’s capacity to hold the executive accountable, they can, especially when grounded in tangible events, offer valuable insights into its performance. The implications of these high-profile corruption scandals and the delayed and unclear court decisions have resulted in public distrust in the court. However, distrust in the judicial systеm has been high since the democratic transition more than three decades ago.

• According to a 1994 survey conducted by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation and the Academy of Sciences, court was the second most corrupt institution at soum levels (Mont 2002).

• In 2005, a public opinion survey conducted as part of the ‘Judicial Reform Program’ found that 90 percent of the respondents believed court decisions favor wealthier and more influential individuals over ordinary ones (Чимид 2006, p. 157).

• In 2008, the Open Society Foundation surveyed professionals in the judicial systеm and found that 54 percent of the participants believed ‘conditions for impartiality and independence are not met in Mongolia’ (White 2008, p. 15). To the statement ‘interference of other organs of the state and politicians is high,’ 42 percent agreed and 38 percent said not sure. The research also collected anecdotal evidence from anonymous judges on how prominent political figures directly attempted to interfere in their decisions.

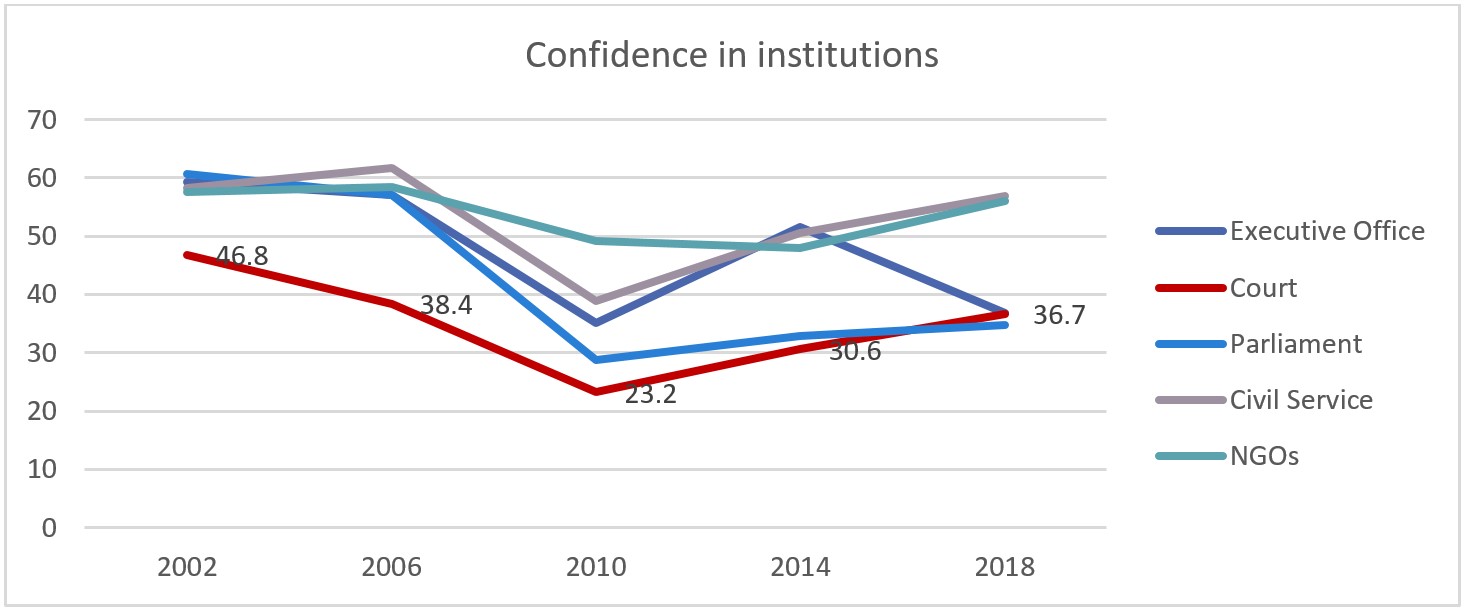

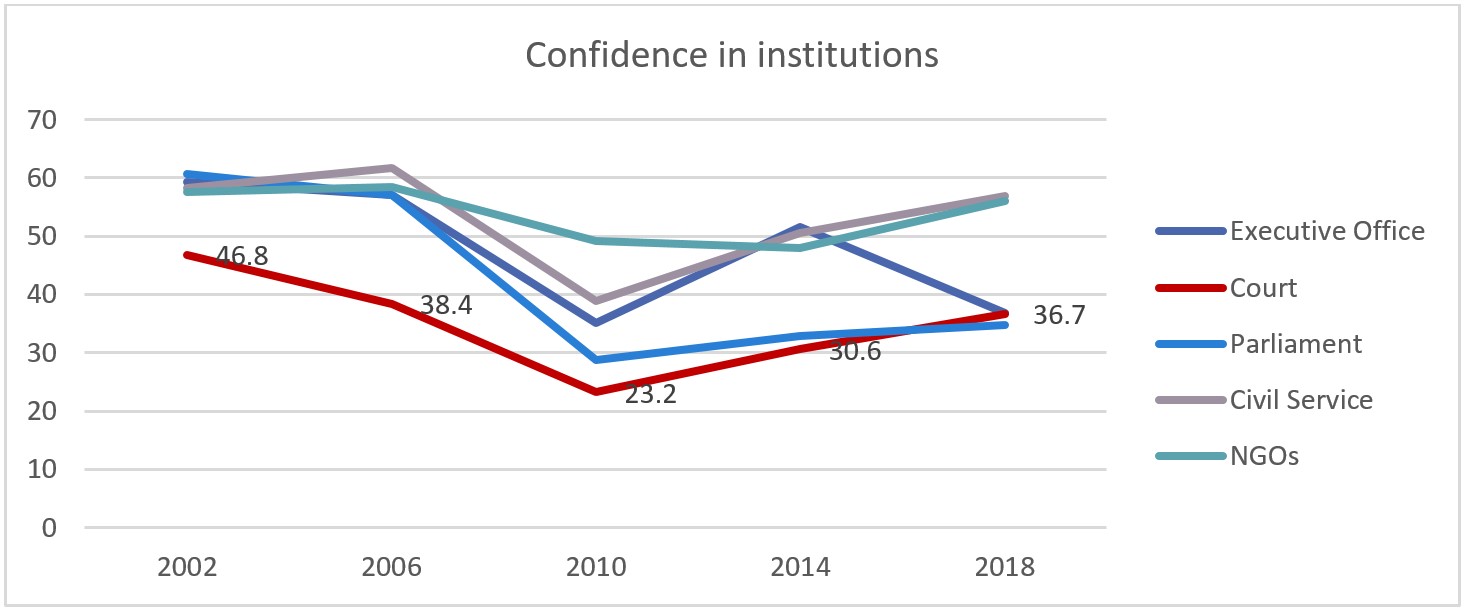

• The Asian Barometer Survey in 2018 found that the proportion of respondents saying they trust the Courts was 36.7%, slightly higher than trust in parliament (34.7%) and much lower than trust in the president and prime minister (68.0%). Figure 2 shows that trust in the courts has been lower than in other institutions (Asian Barometer Survey).

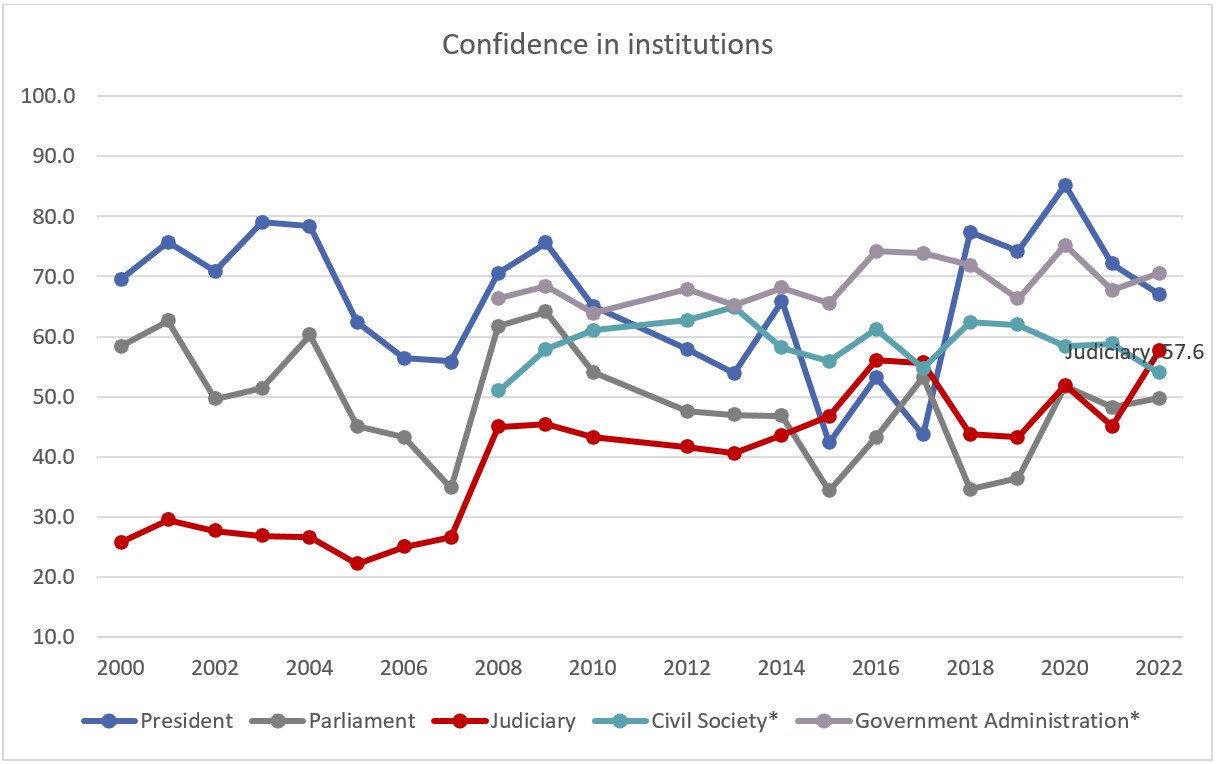

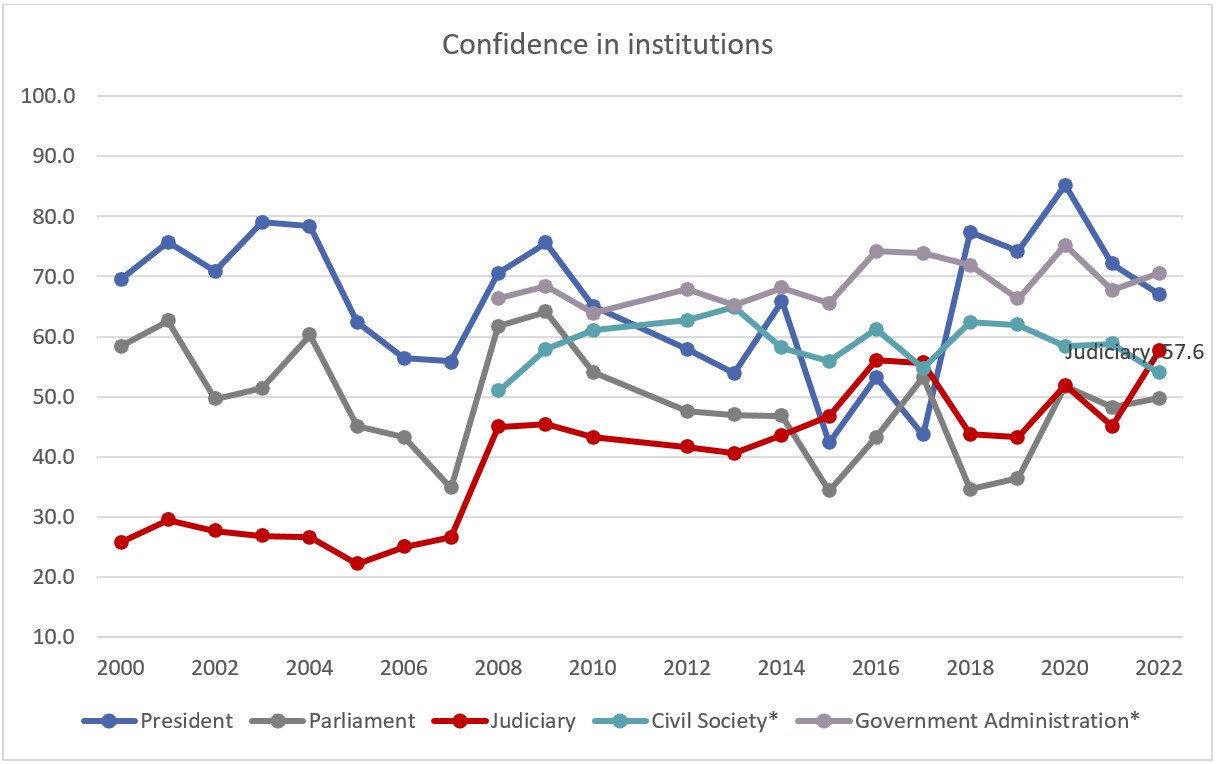

• As the Sant Maral Foundation’s public opinion surveys between 2007 and 2022 show, the proportion of respondents indicating trust in the courts is higher than those reported in the Asian Barometer Survey mentioned above. However, a similar trend of lower levels of trust in the courts compared to other institutions is observable.

Figure 2. Proportion of respondents answering ‘trust or trust a lot’ in different institutions, ABS 2002-2018

Source: Asian Barometer Survey, author’s calculation

Figure 3. Confidence in institutions 2000-2022

Source: Sant Maral Foundation, 1992-2022

4. The Judicial Branch’s Independence

To assess the judicial branch’s independence, we look at the factors that affect it, including legislation and structure of the judicial systеm, budget allocation, selection and dismissal procedure of judges, and ethical and disciplinary proceedings of the judges.

Table 1. Legal and institutional capacity of the Judicial Branch (2017-2022)

|

Key capacity areas

|

Status

|

|

Legislation

|

Constitution of Mongolia (1992) stipulates the independence of court and impartiality of judges.

Laws: The organization and operations of courts and the Judicial General Council are regulated by law. Law on the Judiciary (2021); Law on Judicial Admіnistration; Law on the Legal Status of Judges; Law on the Legal Status of Citizens’ Representatives in Court Trials; and Law on Mediation.

|

|

Structure

|

Three-tiered systеm: Supreme court, provincial and capital city courts (appellate), and soum/inter-soum and district courts (first instance).

Courts: Courts of Ordinary Jurisdiction (civil and criminal cases); Admіnistrative Court (admіnistrative cases) and Constitutional Court (constitutional disputes and cases)

|

|

Budget allocation (% of total government expenditure)

|

Courts are financed by the State. Between 2012-2022, on average 0.70% of the government expenditure was spent to finance judicial sector. The highest was in 2015 reaching 0.85% and the lowest in 2018 at 0.62%.

|

|

Selection and dismissal procedure of key persons

|

Judicial General Council is responsible for selection.

President of Mongolia is in charge of appointing.

|

The Constitution of Mongolia (1992) assures the structure and independence of the judicial systеm in Articles 48-55. Mongolia’s three-tiered judiciary comprises the Supreme Court, aimag (provincial) and capital city courts, and soum and district courts. As stated in Article 48, courts operate based on specific laws, receive financing from the state budget, and the state guarantees their economic operations. The Law on Courts (2012) governed these institutions until the Law on the Judiciary superseded it in 2021. Other pertinent legal documents include the Law on Judicial Admіnistration, the Law on the Legal Status of Judges, the Law on the Legal Status of Citizens’ Representatives in Court Trials, and the Law on Mediation.

4.1. Independence and Impartiality of the Judiciary

An understanding of the historical and legislative context is required to understand whether the Judiciary branch has handled the Development Bank of Mongolia and other prominent corruption cases with independence and impartiality. Article 49.2 of the Constitution asserts, “Judges shall be impartial and bound only by the law. Interference in the judges’ duties by any individual or official—including the President, National Parliament members, Government officials, political party representatives, or members of other voluntary organizations—is prohibited.” The Judicial General Council plays a crucial role in safeguarding judicial independence, overseeing the selection of judges, and protecting judges’ constitutional rights (Article 49). However, the practical implementation of Article 49, beyond mere rhetoric, remains questionable.

Political figures influence the selection of judges. While the Judicial General Council conducts preliminary selections and proposes candidates, Parliament nominates them. Ultimately, it is the President of Mongolia who appoints them. Some scholars posit that since the Judicial General Council conducts the initial presentations, this ensures a degree of independence for judges from political sway. However, opposing views, including those from the OSCE (2021), emphasize the President’s considerable influence over aspects such as court organization, judges’ statuses, appointments, and dismissals.

In 2019, legislative amendments granted the National Security Council, comprising the president, prime minister, and the speaker of parliament, authority over judge appointments and dismissals. These amendments led to the removal of 17 judges in June 2019. Many civil society organizations, including Transparency International, voiced their disapproval, highlighting significant threats to the rule of law (Transparency International 2019). Nonetheless, the reformed Law on Judiciary in 2021 provided clearer guidelines on judicial appointments and bolstered measures to ensure the judiciary’s independence (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022).

The Judicial General Council’s autonomy has historically been in question. The specifics of its organization remain ambiguous in the Constitution. Ex-Member of Parliament Lundendorj, referencing the 1992 Constitution draft, revealed that the UN Human Rights Council had cautioned about a nebulous Judicial General Council structure, warning of potential dominance by the ruling parliamentary party (Лүндэндорж 2021). Over three decades, the Judicial General Council’s structure underwent five notable shifts:

• 1992-1996: Dubbed the ‘President- Judicial General Council’ phase. The President appointed 10 out of the 12 council members, with the Council selecting its chair.

• 1996-2002: A ‘Ministry of Justice-President’ hybrid era saw the Ministry’s amplified role. Given the period’s parliamentary instability, the Council experienced turbulence; the Judicial General Council Chair switched five times in six years, highlighting the Council’s political susceptibility.

• 2002-2012: Termed the ‘President – Self Governance of Judges’ phase. Of 14 members, 57% were judges chosen by aimag/capital city judges’ assemblies.

• 2012-2020: Essentially evolved into an ‘Extension of the President’s Office’. All Judicial General Council members were presidential appointees, sidelining representatives from the Ministry of Justice and Parliament, which underscored the President’s accruing power. A survey revealed 44 percent of 144 judges felt the president overly dominated the judicial systеm (Мөнхсайхан, Цагаанбаяр, Алтансүх 2015). Notably, 13 out of 173 judges claimed unjustified presidential rejections for various appointments.

• 2021 onwards: The ‘Self Governance and Parliament’ era commenced. A pivot toward parliamentary inclusion took place to mitigate the president’s outsized role. Subsequent amendments mandated that half of the Judicial General Council members were to be chosen by the Judges’ General Assembly and the rest by parliament (Law on the Judiciary of Mongolia, Article 76.2, 2021). The OSCE’s 2021 evaluation of this Law recommends excluding top executive officials and MPs from potential membership, a stipulation not yet incorporated, which might perpetuate concerns of undue executive and political influence on the Judiciary (OSCE 2021).

Numerous international monitoring bodies have underscored the importance of improving Mongolia’s judge selection and appointment procedures to exclude political entities, particularly the president and parliament. Yet, the modifications to the structure of the Judicial General Council and the judge selection process suggest enduring political sway. It is interesting to note that prior assessments of Mongolia’s judicial reform, including its independence, have highlighted both political party influence and the co-opting of donor-funded judicial reform initiatives by the country’s judicial elite (White B. T. 2009).

4.2. Responsiveness and Timeliness

Assessing the timeliness and responsiveness of the judiciary, especially in the context of a corruption case, requires a keen focus on the duration, efficiency, and adaptability of judicial proceedings.

A 2018 assessment by Transparency International showed that only 24 percent of corruption cases in Mongolia were prosecuted, while 76 percent were dropped by prosecutors. Mongolia should eliminate any interference by the National Security Council in the independence of the anti-corruption agency and establish a well-resourced and specialized anti-corruption court (Merkle 2018). The Development Bank corruption case shows that lawsuits related to corruption cases generally take significant time to resolve. Some disputes have been pending in court for 69 months.

5. Conclusions

The assessment of horizontal accountability in Mongolia, particularly focusing on the judiciary’s role in combating corruption scandals, highlights several critical points. The analysis of Mongolia’s V-Dem Horizontal Accountability Index shows recent declines suggesting a need for renewed emphasis on reinforcing mechanisms for state entities to hold each other accountable. Public perceptions provide valuable insights into the judiciary’s performance, high-profile corruption scandals and delayed and unclear court decisions have contributed to public distrust in the judiciary. This distrust is not a recent phenomenon, as it has persisted since Mongolia’s transition to democracy more than three decades ago.

Assessing the timeliness and responsiveness of the judiciary in corruption cases underscores the need to focus on the efficiency, duration, and adaptability of judicial proceedings. The delays in lawsuits related to corruption cases call for enhanced efficiency and effectiveness in the judicial systеm.

While the Mongolian Constitution and subsequent legislative amendments assert the impartiality and independence of the judiciary, the practical application of these provisions suggests significant political influence, especially from the executive branch. This influence is evident in the appointment process of judges, the structure and evolution of the Judicial General Council, and the considerable sway of political figures over judicial decisions and reforms. Despite international concerns and recommendations, political interference in Mongolia’s judicial sector persists, and the judiciary’s autonomy remains questionable.

Addressing Mongolia’s horizontal accountability challenges demands comprehensive reforms to enhance the independence, capacity, and transparency of its judiciary. These reforms should prioritize reducing political influence in the judiciary, improving efficiency in handling corruption cases, and fostering public trust in the judicial systеm. Furthermore, the potentials for establishing a specialized anti-corruption court should be carefully examined to combat corruption and bolster judiciary’s capacity to hold the executive accountable. ■

References

Adiya, Amar. 2022. “Backlash over Development Bank of Mongolia Exposes Social and Political Tensions.” Mongolia Weekly, April 27. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://www.mongoliaweekly.org/post/backlash-over-development-bank-of-mongolia-exposes-social-and-political-tensions

Asian Barometer Survey. (n.d.). Datasets from the Asian Barometer Survey Wave 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. Asian Barometer Survey.

Bayartsogt, Khaliun. 2018. “A scandal in Mongolia: heads roll in government after US$1.3m SME fund embezzlement.” South China Morning Post, November 6. Accessed June 10, 2023. https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/east-asia/article/2171965/scandal-mongolia-heads-roll-government-after-us13m-sme-fund

Bekmurzaev, Nurbek. 2023. “Mongolia embroiled in a major corruption scandal over the allocation of educational loans.” GlobalVoices, May 29. Accessed June 10, 2023. https://www.scribd.com/article/649063238/Mongolia-Embroiled-In-A-Major-Corruption-Scandal-Over-The-Allocation-Of-Educational-Loans

Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2022. BTI 2022 Country Report — Mongolia. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung. Accessed April 16, 2023. https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-report/MNG#pos4

Davaabazar, B. 2022. “ТООЦООЛОЛ: 40 их наяд төгрөг яаж гарсан бэ?” ikon.mn, December 9. Accessed June 10, 2023. https://ikon.mn/n/2qpk

Dierkes, Julian. 2022. “Mass Protests in Mongolia Decry ‘Coal Mafia,’ Corruption.” The Diplomat, December 6. Accessed June 10, 2023. https://thediplomat.com/2022/12/mass-protests-in-mongolia-decry-coal-mafia-corruption/

Guarnieri, Carlo. 2003. “Courts as an Instrument of Horizontal Accountability: The Case of Latin Europe.” In Democracy and the Rule of Law, ed. J. M. Maravall and A. Przeworski, 223-241. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Law on the Judiciary of Mongolia, 2021 Article 76.2.

Lkhaajav, Bolor. 2017. “Ahead of Presidential Election, Mongolia Corruption Scandal Has a New Twist.” The Diplomat, June 19. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://thediplomat.com/2017/06/ahead-of-presidential-election-mongolia-corruption-scandal-has-a-new-twist/

Merkle, Ortrun. 2018. “Mongolia: Overview of Corruption and Anti-Corruption.” Anti-Corruption Helpdesk. Transparency International. Accessed April 16, 2023. https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/assets/uploads/kproducts/Country-Profile-Mongolia_2018.pdf

Mont, Robert La. 2002. “Some Means of Addressing Judicial Corruption in Mongolia.” Policy Documentation Center. Accessed April 8, 2023. http://pdc.ceu.hu/archive/00002274/01/Judicial_Corruption_in_Mongolia.pdf

OSCE. 2021. Opinion on the Law on the Judiciary. Warsaw: Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/1/8/509672.pdf

S. Undarmaa. 2023. “Хөгжлийн банкны 460 гаруй хавтаст хэрэг, 257 оролцогч.” News.mn, February 15. Accessed June 10, 2023. https://news.mn/r/2627570/

Sant Maral Foundation. 1992-2022. Politbarometer Dataset. Ulaanbaatar: Sant Maral Foundation. https://www.santmaral.org/publications

Transparency International. 2019. “Rule of Law and Independence of Judiciary Under Threat in Mongolia.” July 4. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://www.transparency.org/en/press/rule-of-law-and-independence-of-judiciary-under-threat-in-mongolia

Tumurtogoo, Anand. 2023. “A charter under siege.” Asia Democracy Chronicles, February 15. Accessed June 10, 2023. https://adnchronicles.org/2023/02/13/a-charter-under-siege/

Varieties of Democracy. 2023. Country Graph: Mongolia Horizontal Accountability Index. https://www.v-dem.net/data_analysis/CountryGraph/

White, Brent T. 2008. Report on The Status of Court Reform in Mongolia. Ulaanbaatar: Open Society Forum.

______. 2009. “Rotten to the Core: Project Capture and the Failure of Judicial Reform in Mongolia.” East Asia Law Review 4, 209-275.

Лүндэндорж, Н. 2021. “ШЕЗ-д нэртэйгээр нь намайг оруулахгүй гээд журамдаа биччихгүй яасан юм бол гэж инээд хүрч сууна.” ikon.mn, Accessed April 6, 2023. December 13. https://ikon.mn/n/2ep5

Мөнхсайхан, О., Цагаанбаяр, Г., Алтансүх, Ж. 2015. Монгол улс дахь шүүхийн захиргааны загвар: тулгамдсан асуудал, шийдвэрлэх арга зам. Улаанбаатар: ННФ.

Чимид, Б. 2006. Монгол Улсын Шүүхийн эрх мэдлийн стратеги төлөвлөгөөний биелэлтийг зохион байгуулсан нь. Улаанбаатар.

Шүүхийн шийдвэрийн хураангуй. 2019. Capital City Court of Civil Appeals. Accessed March 6, 2023. https://appealcourt.mn/site/huraangui/

■ Tamir Chultemsuren is the Vice Dean of the National University of Mongolia’s School of Arts, Sciences and Social Sciences, and holds a doctoral degree in Sociology. Dr. Chultemsuren is one of the co-founders of the Independent Research Institute of Mongolia (IRIM) and has been Chairman of the Board of IRIM since 2011. Having attended various academic seminars and functions across the U.S., Ireland, Hungary, Portugal, Turkey, Finland, Kazakhstan, Austria, the United Kingdom, and South Korea, Tamir has diverse and in-depth experience in engaging partners in cross-cultural settings. His areas of expertise are social research—civic participation, mass protest, and public perception; policy research—education policy and institution strengthening, monitoring, and evaluation; and project management.

■ Dolgion Aldar is a research professional focused on promoting evidence-based policy-making and social cohesion in Mongolia. She spent five years as CEO of the Independent Research Institute of Mongolia (IRIM), one of the first organizations to promote independent and third-party research in the country. Dolgion is currently working with the Asia Foundation in Cambodia as Program Director for Ponlok Chomnes Data and Dialogue for Development. Prior to this role, she served in UNDP in Timor-Leste as a Socio-Economic Expert. She currently serves as a Secretary of the Research Committee on Social Indicators of the International Sociological Association. She is a member of the Social Well-Being Research Consortium in Asia and the Asia Democracy Research Network. Dolgion holds a master’s degree in Political Science from the University of Manchester, and both a master’s and a bachelor’s degree in Sociology from the National University of Mongolia.

■ 담당 및 편집: 박한수_EAI 연구원

문의: 02-2277-1683 (ext. 204) hspark@eai.or.kr

![[ADRN Working Paper] Assessing Horizontal Accountability in Mongolia: Weak Judiciary Combatting Corruption Scandals](/data/bbs/kor_workingpaper/2023091323165176354522.jpg)

![[한국 민주주의 퇴행 진단 시리즈] ⑤ 한국 민주주의 위기와 ‘아래로부터의 퇴행’?](/data/bbs/kor_workingpaper/20250515144319733110491(0).jpg)

![[한국 민주주의 퇴행 진단 시리즈] ④ 한국 정치엘리트와 민주주의 퇴행](/data/bbs/kor_workingpaper/20250515143956733110491(0).jpg)