![[ADRN Special Report] Ups and Downs of Direct Democracy Trends in Asia: Country Cases](/data/bbs/eng_special/20221101134931043485800.png)

[ADRN Special Report] Ups and Downs of Direct Democracy Trends in Asia: Country Cases

Special Reports | 2022-10-31

Asia Democracy Research Network

Asian democratic countries are incorporating mechanisms and ideas of the direct democracy into their political system. Still, there is a need to improve the quality of citizen engagement and to harmonize it with representative democracy system. In order to examine diverse background and trends of direct democracy within Asia, the Asia Democracy Research Network (ADRN) has been conducting research on Direct Democracy based on country cases since 2021. As a part of this research, EAI launched a special report series composed of seven special reports, covering the cases of Indonesia, India, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Mongolia, and Malaysia.

Francisco A. Magno [1]

DLSU Institute of Governanace

Direct democracy includes people’s initiatives, referendums, and plebiscites where citizens vote on specific policies instead of electing candidates. There are scholars who limit the scope of direct democracy to mechanisms where secret balloting is conducted. However, others acknowledge citizen assemblies and public participation in government planning and budgeting as equally important forms of direct democracy. The broader view of direct democracy that encompasses referendums, recall voting of elected officials, and citizen participation in the budget process is taken in a set of studies conducted under the Asian Democracy Research Network.

The nature and characteristics of direct democracy were examined in seven Asian nations, namely India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mongolia, Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. Each of the country studies specified the direct democracy mechanisms and the contexts that shaped their emergence. The key mechanisms identified are referendums, recall of public officials, and people’s initiatives. Various authors examined the claims for or against these mechanisms, and identified the actors, demographics, and levels of government that were involved in their implementation. They also looked into the effectiveness of direct democracy mechanisms in fostering reform and improving the overall quality of democracy. Finally, they considered the new trends, including the use of digital technology, that are coming out in the exercise of direct democracy.

The evolution of direct democracy in Asia can be better understood by looking at their underlying historical contexts. For instance, the rise of vote-based direct democracy mechanisms can be linked to the international surge of democratization in the 1980s and 1990s. The Philippines provides an interesting case for the institution of direct democracy mechanisms following the removal of an authoritarian government in 1986. A new Constitution that provides the framework for democratic governance was passed in 1987. Among its key provisions is the people’s initiative which is one of the modes for amending the Constitution upon a petition of at least twelve percent of the total number of registered voters with the Commission on Elections, of which every legislative district must be represented by at least three percent of the registered voters there. The Philippine Initiative and Referendum Act of 1989 is an enabling law which allows voters to directly initiate the passage of laws and to call for national and local referendums.

In Thailand, the referendum was used as a mechanism to get the people’s approval of Constitutional changes, including those made in 2007, and in the latest revisions drafted in 2016. The issues surrounding the Constitution were not fully discussed prior to the referendum as the military government curtailed debates and stifled any form of opposition against the proposed charter. Under the new constitution, the prime minister does not need to be an elected member of the House, and would be chosen by the full Parliament, including the 250 members of the Senate who are appointed by the military. The current Constitution of Thailand, officially promulgated in 2017, provides a system of people’s initiatives to recommend legislation and recall elected officials.

In Indonesia, the referendum was authorized as a means of amending the 1945 Constitution under Law Number 5/1985. However, this rule is no longer valid after it was revoked in 1999. A notable example where the referendum was conducted concerned asking the residents of East Timor whether they wanted to stay as a province of Indonesia or become an independent state. The referendum was carried out following a United Nations resolution calling for the right to self-determination of the East Timorese people. The economic crisis and political reforms in Indonesia facilitated the government’s decision to hold the May 1998 referendum in East Timor under UN supervision.

The provision on people’s referendum is found in Article 24 of the 1992 Constitution of Mongolia. The 1995 Law on People’s Referendum specified that the authority to initiate a national referendum belongs to the President and the Parliament. The law has several drawbacks, including restrictions on citizens’ rights to initiate a referendum. It also lacks clarity on the preconditions for holding a referendum. Since its adoption, not a single referendum was held in the country. In 2016, the Law on People’s Referendum was amended to make it consistent with the Law on General Elections that adopted automated election tools.

A Westminster parliamentary structure was introduced in Sri Lanka in 1944. The institutions established under this structure were governed by Commonwealth parliamentary traditions, in addition to the constitution that was in force at the time. Among these Commonwealth parliamentary traditions was the ability for citizens to directly engage in government through instruments such as Private Member Bills, Public Petitions, and Parliamentary Questions. However, there are challenges in accessing and being able to meaningfully use these mechanisms.

Aside from referendums, the recall of public officials, and people’s initiatives on policy reform, citizen participation in planning and budgeting especially at the sub-national level have become an important feature of direct democracy in Asia. In India, the 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendment Acts enacted in 1992, made provisions for Gram Sabhas, an assembly of the electorates, and Ward Committees. Both the Acts elaborated the functions of Gram Sabhas and Ward Committees respectively, which included participation in planning and monitoring of all local development work.

In the past two decades, Philippine civil society organizations (CSOs) have become critical players in ensuring the integrity of public service delivery. Formal and informal spaces for citizen participation are now available in the areas of public financial management. The Philippines developed a decentralized system of government with the passage of the Local Government Code of 1991. Local development councils in every province, city, municipality, and barangay determine the use of the local development fund which represents 20 percent of the Internal Revenue Allotment from the national government. Under the law, a quarter of the seats in these councils and other local special bodies are occupied by CSO representatives.

In the case of Thailand, participatory budgeting was discussed in the Thai Development Strategic Plan of 2008–2012. In Strategy 2, the participatory planning and budgeting strategy of the Ministry of Interior emphasized the importance of strengthening local communities through the people’s budget. There are local governments that adopted participatory budgeting, such as Amnat Charoen Province, Yala Province, Ko Kha Subdistrict Municipality, and Lampang Province.

In Indonesia, various CSOs provided technical assistance and training at the local level on planning and budgeting issues. This became especially significant as the national government implemented the Village Law in 2015 to accelerate poverty alleviation in the country. Under this policy, villages have the authority to manage their own resources for development purposes. There were concrete results from the implementation of programs such as the establishment of various basic infrastructures in many villages. However, the number of cases of misuse of village funds by village heads showed that there were still serious problems in the governance of program implementation and accountability.

In Mongolia, a Law on Deliberative Polling was ratified in 2017. It stipulates that executive and legislative organizations at all levels can hold deliberative polling to identify issues and consult with citizens on policy priorities. The deliberative polling comprises a random and representative sample of the population to engage in dialogue with experts using carefully balanced briefing materials and questionnaires. This deliberative polling process is a requirement in making authoritative decisions such as amending the Constitution, selecting projects to be funded by the local development fund, and the planning of cities and green facilities in public spaces.

The use of digital technology and online engagement platforms have gained significant attention as direct democracy mechanisms in Asia. In India, several governmental initiatives have tried to leverage technology for soliciting public consultations in public policy planning and monitoring. For example, Mobile Vaani is a mobile-based voice media platform of Gram Vaani. It has a unique model wherein it enables people to call up from their basic analog mobile phone to a designated phone number and register their complaints in their local dialect. Another example in India is Jandarpan which is an initiative of Samarthan – Centre for Development Support working in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh since 1995 on participatory governance. The Jandarpan platform was developed during the pandemic to facilitate the migrant workers the access of benefits from the public programs.

The role of social media in Malaysia has evolved to fill the gap in political literacy. Social media has helped boost movements like “Wednesday Vote” (Undi Rabu) and “Let’s Go Home to Vote” (Jom Pulang Undi) which were devised by netizens and CSOs to encourage the citizens to get out and vote. Many first-time voters gained basic knowledge regarding the state of national politics, voting, and voters’ rights from these platforms. In Thailand, the use of social media and websites like www.change.org, have become tools through which citizens send a signal to the government, especially on important issues in the country. Citizens in Indonesia also use digital technology to access information and monitor public accountability with the help of open government partnership programs.

The E-Governance program in Mongolia introduced 25 types of E-services. Since 2013, a call center provides a platform to get citizens’ feedback, and this was expanded in 2019 to a Government Public Communication Center which receives feedback and provides referrals to relevant government agencies. The deployment of civic technology in the Philippines contributes towards enhancing citizen participation in monitoring public service delivery. The DevLIVE is a mobile application developed by the United Nations Development Programme. It has been adopted by the Department of the Interior and Local Government to become an online platform for collecting citizen feedback on the quality of local infrastructure projects.

The key direct democracy mechanisms such as referendums, recall of public officials, and people’s initiatives are formally available in the legal systems of the majority of countries in Asia covered by the study. However, these mechanisms have not been widely applied in practice. Many initiatives at the national level have faltered, while a few cases of successful implementation were seen at the sub-national level. While the principle of democratic governance is extolled in the Constitutional provisions that authorize these mechanisms, there are significant practices that use referendums, recall of public officials, and people’s initiatives to undermine democracy and promote authoritarianism.

There are encouraging trends in the emergence of formal and informal governance avenues for integrating citizen participation in local planning and budgeting, as well as utilizing digital platforms to foster social accountability. However, there is still a need to enhance the quality of citizen engagement as there are tendencies for the direct democracy mechanisms to yield limited results due to the token nature of civil society participation. There is a tendency for elected officials under the dominant system of representative democracy to look down on the mandate of non-elected stakeholders in the policy decision-making process. This dilutes the effectiveness of direct democracy that is supposed to provide voice mechanisms to sectors that are excluded in voting processes that focus on candidates. In this sense, it is important that representative democracy and direct democracy mechanisms are both attuned in efforts to foster democratic values, institutional frameworks, and practices that genuinely support the promotion of democratic quality in the various countries in Asia. ■

[1] Senior Fellow and Founding Director, DLSU Institute of Governance

Examining Direct Democracy in Indonesia

Devi Darmawan [1] , Sri Nuryanti [2]

Indonesian National Research and Innovation Agency

Abstract

As a country with a representative democratic system, Indonesia once had regulated the referendum mechanism to amend the constitution and implemented referendums as part of direct democracy practices. However, the referendum practice on East Timor’s case worsened the political situation at that moment, which affected the government decision to permanently revoke the law on referendums. The feasibility of executing another referendum in order to amend the constitution is hardly impossible. Accordingly, the trend of implementing other direct democratic practices remains wide open, including citizen initiatives to deliberate active public participation at the local level. Based on that proposition, this paper tries to examine referendum practices in Indonesia, their impact, and feasible ways to sustain more direct democratic mechanisms to foster public participation and engagement with the government agenda to strengthen democracy. The result of this paper illustrates the possibility to utilize direct democracy at the local level by considering the opportunity provided by the Village law as well as the growing digital technology that created a new public sphere for better engaging the society.

Keywords: Referendum; Direct Democracy; Indonesia

1. Introduction

Democratic regimes are now fragile, easily backsliding into authoritarian regimes. The global democracy index has illustrated the pattern of democratic decline across countries worldwide. However, there is hope of sustaining democratization due to the broad support that exists for deepening democracy globally. Based on the survey conducted by Pew Research Center in 2017, roughly a majority of nations support both representative and direct democratic systems. Only nations with less education and higher levels of dissatisfaction with the way democracy is currently working in their country are more willing to consider non-democratic alternatives such as government by military rule (Wike et al. 2017). The survey finds that there is support within Indonesia for military rule as a way to govern, although the country transitioned to a democratic regime in 1999 (Wike et al. 2017). The country has varied between a representative democratic system and a direct democratic system.

However, some democratic scholars have indicated concern about Indonesia’s direct democracy practices. They seem to worry about the capacity of citizens and their competency to decide critical policy issues. In other scenarios, democratic governance may make it likely that the elite could manipulate their participation into passing harmful policies (Matsusaka 2004, 186). Consequently, this generates criticism of direct democracy practices. One of the most prominent criticisms of direct democracy is that voters lack the competence to make policy decisions. Indeed, decades of survey research have shown that most voters are uninformed to the point of ignorance about public policy, politics, and government in general. In other words, the lack of competence among voters appears as the lack of information itself. In any case, the argument that voters are incompetent and uninformed would seem to cut against democracy in general, rather than against direct democracy alone (Matsusaka 2004, 198).

Another criticism mentioned is that voter ignorance and apathy allow organized and wealthy special interests to use the tools of direct democracy for their own benefit and to the detriment of the public. This would have a damaging effect on policies. Oftentimes, direct democracy mechanisms are seen as a tool that empowers populist authoritarians. However, in fact direct democracy mechanisms have their own advantages and disadvantages when it comes to real politics. The advantages of direct democracy practices can depend on the feasibility of mass gatherings which require voters to gather in one place, and include enabling specific issues to be discussed and debated directly, ensuring inclusiveness by engaging society to influence the decision making process, allowing majority support to be considered and win out, facilitating community meetings to assign or appoint government officials who hold administrative posts, and allowing voters to submit legal drafts as well as propose amendments the constitution based on community support.

However, there are also disadvantages of direct democratic practices that can endanger future democratic consolidation. Recent studies have shown that direct democracy has the tendency to expand authoritarianism by empowering populists to rise and make use of the popular vote, such as by using referendums to be an effective mechanism to get into power (Collin 2019). In fact, direct democracy is a normal feature of healthy democratic systems, rather than a bug that endangers liberalism. Referendums may function as part of the system of institutional checks and balances that maintain liberal order, or they can undermine it (Collin 2019). Hence, it was critical to arrange such institutional constraints on referendums to prevent them from working against democratic notions.

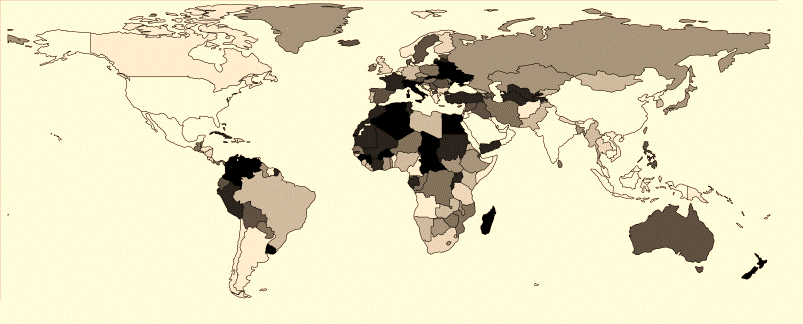

Despite the existing criticisms toward direct democracy practices, direct democracy continues to be implemented in waves. As the number of countries with representative democratic systems has increased, a similar trend occurred with direct democratic system’s implementation. Recent studies have illustrated a growing number of direct democracy practices around the world because they influence government in a better way (Matsusaka 2004, 201). The spread of such practices was triggered by the rapid development of technology that enables citizens to access information and participate directly in policy decisions or policy processes through referendums or initiative mechanisms. Mechanisms of direct democracy (MDDs) have been used in both dictatorships and democracies; in presidential and parliamentary regimes; in poor, developing, and rich countries; in federal and unitary states; in both the south and the north; at the local, regional, and national levels of government; in times of joy and in times of trouble. Almost every imaginable political subject has been put forth for public consideration at one time or another (Larry 2020, 141). The regions with the highest level of direct democracy practices are Eastern Europe and Central Asia, followed closely by the so-called developed world (Western Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand). The least direct democratic regions in the world are the southeast. The Asian continent is certainly weak in any aspect of direct democracy, be it a referendum or an initiative (Altman 2015, 17).

Unfortunately, Indonesia has been considered at the lowest end of the spectrum of direct democracy practices due to its straight implementation of a representative democratic system. In fact, in the trajectory of the country’s democratic transition, Indonesia has held referendums as a direct democratic mechanism. This paper aims to examine the direct democracy mechanisms available in Indonesia, with a specific focus on implementing referendums. The paper is broken into three subsections. First, we reflect on referendum practices in Indonesia. Second, we examine the current trends of referendum practices in Indonesia, and finally we explore the feasibility of sustaining direct democracy practices in Indonesia.

1.1. Problems and Significance

This article evaluates the existing direct democracy mechanisms and the feasibility of adopting and developing direct democracy practices in Indonesia, both through referendums and initiatives. This study aims to contribute to the political discourse and prevent democratic erosion. Further, it aims to highlight the importance of public engagement in influencing public policies or political decisions by assessing the compatibility of direct democracy mechanisms in Indonesia.

1.2. Literature Review

Democracy is a system that is completely responsive to all its citizens. While there are various definitions of democracy, we describe democracy as a system of government with four key elements: ⅰ) a system for choosing and replacing the government through free and fair elections; ⅱ) active participation of the people, as citizens, in politics and civic life; ⅲ) protection of the human rights of all citizens; and ⅳ) a rule of law in which the laws and procedures apply equally to all citizens (Diamond and Morlino 2004, 22). However, when it comes to the democratic practices of today, the concept of democracy has many variants. Even though direct democracy is often seen as conflicting with representative democracy, both democratic systems have supporters across the globe. Representative democratic systems have been more widely adopted in comparison to direct democratic systems.

According to Pew Research’s survey, at least 38 countries show a preference for committing to representative democracy (Wike et al. 2017). This high number shows that countries support democratic representation as well as direct democracy by considering some advantages of well-functioning democracy. Proponents of direct democracy argue that it has two main virtues (Matsusaka 2004). First, direct democracy allows voters a way to circumvent representative institutions that may have been captured by elites or other special interests. Second, compared with meetings, elections allow a greater number of citizens to participate directly in political decision making, and this increased participation may enhance the legitimacy of political decisions, even if the decisions themselves do not change (Lind and Tyler 1988).

Essentially, direct democracy and representative democracy differ in the context of public deliberation. Direct democracy roots in the idea of giving citizens the chance to actively participate in the decision-making process of their country. In contrast, representative democracy gives citizens the opportunity to participate in decision making through elected representatives. This main difference is sometimes considered a constraint for representative democracy, since it limits the degree to which public engagement or public participation in decision making is activated. Representative democracy oftentimes focuses its concerns on primary elections and how to increase public participation through voter turnout. Ultimately, active public participation should manifest as more than just casting ballots, since every person has their own opinion on particular issues in their region. This gap has been filled by direct democratic mechanisms such as referendums or initiatives that provide a pathway for citizens to deliver their voices to influence or amend public decisions.

“Referendum” is the term given to a direct vote on a specific issue. This is in contrast to votes cast during elections, which are made in relation to parties or individual candidates and generally reflect voters’ preferences over a range of different issues. Referendums may be held in relation to particular circumstances (e.g., to amend a country’s constitution) or in relation to particular political issues (e.g., whether or not to join an international organization), but are in general held in relation to issues of major political significance.

“Initiatives” are put forth by citizens to provide for the inclusion of constitutional or statutory proposals on the ballot during an election if enough signatures are collected in support of the proposal. The number of signatures required to place an initiative on the ballot varies, but is usually a proportion of the number of voters who voted in the most recent election, or a fixed number of registered voters. Depending on the design of the initiative process, if the ballot measure is passed by voters, it may become part of the state or country’s law. The initiative process therefore provides citizens with an opportunity to directly frame the laws and/or constitution under which they live (Bulmer 2017, 6). Thus, the referendum is a process that allows citizens to approve or reject laws or constitutional amendments proposed by the government. Meanwhile, the initiative is a process that allows ordinary citizens to propose new laws or constitutional amendments via petition. The main difference between initiatives and referendums, therefore, is that citizens can write the former whereas only government officials can draft the latter (Matsusaka 2004).

1.3. Methodology

This study employs qualitative research methods to explore the practice of direct democracy mechanisms in Indonesia. In the process, this research collects data through literature studies on how direct democracy has been held in Indonesian politics. Subsequently, literature and documents such as laws and regulation related to referendum as part of direct democracy mechanisms, article or publication about democratic transitions, and research on public engagement as part of political discourse will be covered in this paper.

2. Indonesia and its Direct Democratic Mechanism Practices

According to Freedom House, Indonesia has made impressive democratic gains since the fall of the authoritarian regime in 1998, establishing significant pluralism in politics and the media and undergoing multiple, peaceful transfers of power between parties (Freedom House 2021). However, the country continues to struggle with challenges including systemic corruption; discrimination and violence against some marginalized groups; tensions related to the independence movement in the Papua region; and the politicized use of defamation and blasphemy laws. In recent years, authorities have responded to recent mass protests against the controversial 2020 omnibus law with violence and repression. During the transition to democracy, Indonesia has implemented a representative democratic system whereas every citizen can vote for their president and representatives directly. However, in its democratic trajectory, Indonesia has combined the direct democracy mechanism into its democratic system by implementing referendums to manage specific critical political decisions for the sake of the people. A referendum was held to decide whether to amend the 1945 Constitution and another to allow East Timor province to vote on their affiliation with Indonesia (Pereira 2006). Indonesia previously had a regulation concerning referendums, Law No. 5/1985. However, this regulation was revoked in 1999 and is no longer a valid legal foundation for future referendums.

Although the legal framework for referendums no longer exists, Indonesia has implemented direct democracy in the past in the form of referendums. As mentioned above, one notable example is the referendum held by East Timor province to vote on their affiliation with Indonesia (Pereira 2006.). During the referendum, the people of East Timor were asked to determine their citizenship status (Soares 2003). East Timor voters were asked whether they would like to remain affiliated with Indonesia or become independent. The East Timor area was historically annexed by Indonesia during Soeharto’s presidency back in the New Order period. The referendum was a consequence of UN resolutions calling for the right to self-determination (Pushkina and Maier 2012). The 1997 Indonesian economic crisis and political reforms in May 1998 facilitated the Indonesian government’s decision to hold a referendum in East Timor under UN supervision. In other words, Indonesia practically has only held one referendum as the amendment of the Indonesian constitution has been held without a referendum process behind it.

Based on Indonesia’s experiences in amending the constitution, the amendment was established four times within 4 years starting from 1999, 2000, 2001 to 2002. The amendment process was ruled out by the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) to respond to the demands of mass protesters from various levels of society to conduct a reform. In this regard, the demands were among others motivated by the practice of administering the state during the centralized authoritarian Suharto regime by using the Constitution as an instrument to perpetuate its power. Therefore, the regulation about referendums in Indonesia was only implemented once in the East Timor referendum on self-determination. It was never a legal framework to generate an amendment for constitutional reform since the political decision to amend the constitution has been passed without a referendum mechanism. Thus, even though there was a regulation on law 5/1985 on referendums, the four times amendments for constitutional reform in 1999-2002 were held in the absence of referendum process and performing based on the people power demands in May 1999. In addition, soon after the loss of Timor Leste after the referendum in August 1999, the regulation was revoked.

Since the law on referendums was revoked, recently a number of people have demanded another referendum in order to amend the constitution, particularly to expand the time limit of presidency in Indonesia. These demands have come from political scientists, political elites, political parties, and non-governmental organizations. Based on their motives to reinstate the referendum mechanism, It is hard to say that these demands stem from public preferences or are rooted within the best interest of the public because it was coming to enable incumbent to run for the next election in 2024 and leverage the chance of incumbent to get in power for three times of presidency period. The other demands to establish referendums ranged from strengthening the bicameral system in Indonesia, rearranging the authority of state institutions of Indonesia, and regulating state policy guidelines (GBHN) into the constitution. The current official government responded to this demand by ruling out any possibility of holding a referendum, stating that a referendum could not be held because it had no legal basis and only existed in the past.

The public response to these calls for referendums to amend the constitution was divided into two opposite groups. The first group was made up of those who were willing to amend the constitution and fully support the referendum, believing constitutional reform would improve the quality of the political and democratic system. The second group felt that the constitution should not be amended through any mechanism because they believed that there was no need to do so (Maiwan 2013). The supporters of the referendum proposal were not victorious, and it does not appear that there is sufficient momentum to implement a referendum in the near future. However, demand for reinstituting referendums is still high, especially from political parties and political elites who support constitutional amendment regarding specific issues.

2.1. The Legal Perspectives of the Referendum in East Timor

Presidential Decree No. 5 issued in 1985 laid out the requirements for amending the 1945 Constitution, stating that such an amendment would only be allowed through a referendum. In this decree, a referendum was defined as an activity to directly ask whether the people agree with the wishes of the People’s Consultative Assembly (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat/MPR) to amend the 1945 Constitution. The decree stated that public opinion must be conveyed in the form of a statement by the People’s Opinion Giver, where The People’s Opinion Giver is a citizen of the Republic of Indonesia who meets the requirements set out in the law. The proposed amendment to the 1945 Constitution was as follows.

The MPR resolves to uphold the 1945 Constitution, does not intend and will not make changes to it, as stated in the MPR Resolution of the Republic of Indonesia Number I/MPR/1983 on the MPR Rules of Procedure, and MPR Resolution of the Republic of Indonesia Number IV/MPR/1983 on the referendum. However, the MPR will implement Article 3 of the MPR Resolution of the Republic of Indonesia Number IV/MPR/1983 on the referendum, and therefore it is necessary to establish a law in governing the referendum. Referendums are held through direct, public, free, and secret public opinion polls. Public opinion is polled using the people’s opinion letter. The decree further stated that the public would be declared to agree with the wishes of the MPR to amend the 1945 Constitution if the results of the referendum as referred to in Article 17 showed that at least 90% of the total number of registered Public Opinion Givers have exercised their right to give public opinion, and at least 90% of the People’s Opinion Givers who exercise their rights express agreement with the will of the MPR to amend the 1945 Constitution.

2.2. The Historical Background of Referendum in East Timor

Timor-Leste is located in the eastern part of the island of Timor with an area of 15,007 km2, and was previously a colony of Portugal known as Portuguese Timor. Due to the struggle of the Revolutionary Front for an Independent Timor-Leste (Fretilin), the region declared independence from Portugal on November 28, 1975. Under the leadership of Soeharto, Indonesia carried out a military invasion that ended in the annexation or forcible incorporation of Timor-Leste into Indonesian territory. Soeharto gained this momentum by taking advantage of the situation in Timor-Leste, which was divided between left and right-wing groups. East Timor was declared the newest province of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia. Indonesia attacked Timor-Leste with a military operation known as Operation Seroja, the largest military operation ever carried out by the Indonesian army. Thousands of troops were mobilized to invade Dili City. They captured and destroyed Fretilin. Around 15,000 Indonesian troops were deployed to secure the second largest city, Baucau. On July 27, 1976, Indonesia officially declared East Timor its 27th province (Handoyo 2014).

The changes in global and domestic politics in Indonesia have implicated the Indonesian policy on Timor-Leste. When Habibie became president, the autonomy of East Timor became a crucial issue. Demands were made by countries beyond Europe and ASEAN for Indonesia to carry out political reforms and particularly to help Timor-Leste determine its own destiny. In this regard, Portugal, as a former colonizer of Timor-Leste, demands the Indonesian government jointly determine the future of Timor-Leste. As a result, Indonesia and Portugal concluded an agreement on May 5, 1999 in New York under the UN corridor (Braithwaite et al. 2012). The agreement laid out a procedure for hosting public opinions in a confidential, direct, and universal manner.

2.3. The Referendum of Timor Leste

The significance of the change in East Timor began in January 1999 when President Habibie announced a “second option” for East Timor to choose between regional autonomy or independence. Habibie asked the then Secretary-General of the United Nations, Kofi Anan, to bridge the disagreement between Indonesia and Portugal over East Timor. An agreement was reached to use the popular opinion poll in consultation with the East Timorese community (Agussalim 2019). At the suggestion of the United Nations, President Habibie held a referendum on August 30, 1999, under the supervision of the United Nations Mission for East Timor (UNAMET) that was attended by the people of East Timor. The police and Indonesian military (Tentara Nasional Indonesia/TNI) accompanied UNAMET, which was the UN mission formed based on UN Security Council Resolution No. 1246 dated May 5, 1999, to carry out the task of polling in Timor-Leste. The climax of the referendum was on August 30, 1999 (Puspita 2008). Simultaneous polls were held throughout and outside Timor-Leste. In the referendum, the people of East Timor answered two questions (Anderson 1993):

a. Do you accept special autonomy for East Timor within the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia?

b. Do you reject the proposed special autonomy for East Timor, which will lead to the separation of East Timor from Indonesia?

The results were announced in Dili on September 4, 1999. A total of 451,792 East Timorese attended the event where the results were announced. Out of a total of 438,968 valid votes, 344,580 (78.5%) people voted for independence, while 94,388 (21.5%) chose to remain with Indonesia. The participation rate in the referendum was very high, with 451,792 people representing 98.6% of all registered voters. The results of the referendum led to the official separation of East Timor from Indonesian control, and the territory was temporarily placed under the authority of the United Nations.

A total of 78.5% of the population of East Timor rejected the special autonomy offered by Indonesia, choosing independence instead. After the referendum results were announced, riots broke out in East Timor. Armed militia groups supported by the TNI went on a rampage and burned the city of Dili and other places (Crouch, H. 2003). Records show that around 1,400 people died and 300,000 people fled to Atambua. This also tarnished Indonesia’s credibility in the eyes of the international community, since the Republic of Indonesia had guaranteed security during the referendum. On October 19, 1999, the results of the East Timor referendum were approved by the MPR, which confirmed that East Timor was no longer Indonesian territory. Historical records reflect that Timor-Leste separated itself from the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia on August 30, 1999 through the implementation of an independence referendum. On May 20, 2002, Timor-Leste was officially declared an independent and sovereign country. The leader of the liberation struggle, Xanana Gusmao, was elected the first president of East Timor.

2.4. The Impact of the Referendum in Timor-Leste on Indonesia

By holding a referendum on East Timor, President Habibie opened a new chapter for democratization in Indonesia. The decision taken by Habibie placed him in a conflicting position. At the national level, Habibi’s image received less sympathy due to the separation of East Timor. On the contrary, on the international side, Habibi’s decision had a positive impact and managed to lift the image of Indonesia, since the country used a direct democratic mechanism to solve conflict and uphold the political preference of locals with regard to East Timor. At that time, the referendum affected national political stability and created massive turmoil in various regions in Indonesia. In other words, the referendum as a feature of direct democracy worked positively for the freedom and self-determination of local citizens in East Timor. However, at the same time, it indeed created a high risk threat for national unity and stability.

3. Current Trends of Referendum Practices in Indonesia

As mentioned above, theoretically, referendums may be held in relation to particular circumstances (e.g., to amend a country’s constitution) or in relation to particular political issues (e.g., whether or not to join an international organization) but are in general held in relation to issues of major political significance. Indonesia previously had a regulation governing referendums as a direct democracy mechanism in the political system. In 1985, Indonesia acknowledged law Number 5, Year 1985 to amend the 1945 Constitution through a referendum. The referendum decreed that it would be held within a maximum of one year from the commencement of the registration of the People’s Opinion Giver until the results of the referendum were submitted to the president as stipulated in the Law Number 5 Year 1985. Article 7 of Law Number 5 Year 1985 stated that the people’s opinion poll was to be conducted simultaneously in one day in all territories of the Republic of Indonesia. The implementation of the referendum would be led by the president. To implement the law, the president should appoint a committee to conduct the referendum, which was to be chaired by the Minister of Home Affairs.

To carry out the referendum, a Referendum Implementation Committee was formed at the provincial, regency/municipality, sub-district, kelurahan/village level, and at the representative of the Republic of Indonesia abroad. For this purpose, the governor, Regent/Mayor, sub-district head, village head, and head of representative of the Republic of Indonesia abroad, due to their respective positions, served as the chair of the Referendum Executive Committee. The Referendum Implementation Committee consisted of elements of the government. To help the implementation of the referendum, a Referendum Supervisory Committee was established. The composition, duties, functions, working procedures, and other matters concerning the Referendum Implementation Committee and the Referendum Supervisory Committee fell under government regulation. To exercise their right, the People’s Opinion Giver had to be registered in the People’s Opinion Giver Register. To be registered in the Register of Public Opinion Givers, the following conditions must be met:

a. Not be a former member of a prohibited organization of the Indonesian Communist Party,

b. Be of sound mind,

c. Possess the right to vote.

A People’s Opinion Giver who, after being registered in the List of People’s Opinion Givers, no longer meets the requirements, is unable to exercise the right to give the people’s opinion. Citizens of the Republic of Indonesia who are former members of prohibited organizations of the Communist Party of Indonesia, including mass organizations of the Indonesian Communist Party, cannot be registered in the People’s Opinion Register. Immediately after a people’s opinion registration ends, a people’s opinion poll is held at the people’s polling place. The People’s Opinion Giver may be present to count the ballots. The results of the count are submitted to the referendum committee. The Referendum Implementation Committee collects the results from each level committee in their designated areas. This referendum practice depicted how the process of direct democracy once lived in Indonesian politics despite the unpleasant results that caused the Timor Leste to be separated from Indonesia.

4. The Feasibility of Sustaining Direct Democracy Practices in Indonesia

4.1. Digitalization and Technology Development to Help Citizens Participate in Politics

The trauma of the political loss in the referendum over East Timor should not be a reason for removing direct democracy practices in Indonesia. There is another direct democracy mechanism that could be established to allow ordinary citizens to express their views about public decisions utilizing digital technology. Technological development has given rise to a new public sphere in cyberspace created as internet penetration expanded. Many scholars have shown the impact of internet penetration in changing social or political interactions between members of the public and their democratic representatives (DiMaggio 2001, Margetts 2013). The internet has facilitated the participation and engagement of individuals with the government agenda at the national and local levels. Nowadays, society can rely on open internet access to acquire information and influence public decisions. The public can utilize apps and social media and join online communities to express their views, raise awareness, recruit activists, and organize protests against specific government policies. Furthermore, they can use social media platforms to promote voting drives and other community engagement initiatives. This recent development of using digitalization to improve citizen participation in democratic processes is often called digital democracy. However, digital democracy is a term filled with political aspirations which emphasize the idea of democratization through technology. A central common idea of these configurations refers to the use of communication technologies for implanting direct-democratic elements into representative democracy.

In other words, digitalization provides new channels and opportunities for sharing information and engaging citizens in policy and legal initiatives and design. In this sense, technology can contribute to revitalizing democracy, enhancing participation, openness, transparency, inclusiveness and responsiveness. Thus, digital democracy implies various new notions of democratic governance. These notions include initiatives for open government (Noveck 2015) to make policy processes more responsive and transparent. By empowering citizens to directly engage with government administrations, policies can be tailored more closely to their needs. The concept of open democracy extends to all levels, from local to nationwide collaborations. In the Indonesia context, digital democracy is available at every level of society, making it possible to scale up alternative mechanisms to address initiatives and engage with the government at the national or local level (province, municipality, or village level). These initiatives could start from planning and budgeting issues.

In fact, initiatives have been implemented by various non-government organizations to provide training and assistance to the public so that they can work together to deliver their opinions to influence local government planning and budgeting. Some of the NGOs that have taken on this role at the national level include associations for election and democracy (Perludem), Indonesian Corruption Watch (ICW), and others. In addition, rapid changes in technology can reduce the gap between government and society. The public can access information through digital technology and participate in creating initiatives to give input to the government. The public can also monitor government accountability in public decision making through Indonesia’s open government partnership program. Moreover, people can create or support petitions to track and tackle the most important topics that affect their lives.

Despite the flourishing of citizen initiatives through digital technology, there are still a few things to be considered with regard to digital participation. The first is the inequality of digital infrastructure. This ultimately lies at the core of the issue with digital participation. Not every citizen has a smartphone, computer or even a stable connection to the internet. For instance, individuals who live outside Java might not have a stable internet connection. Individuals in rural areas often lack the digital infrastructure necessary to boost their digital participation. Many scholars have stated that this is an inevitability of digitalization. There will always be inequality produced in every layer including availability and quality of internet access, ability to use the internet, and the way people use the internet, such as whether they participate and engage the government agenda or get updates on news, etc. This inequality of the digital public sphere translates into a digital divide across society. Second, many people affected by inequality (Dimaggio 2001) themselves lack the technical knowledge or desire to engage with the government digitally. While digital citizenship is visible in several democratic countries, its influence in Indonesia is still debatable. In Indonesia, generally only people with political backgrounds or affiliations use the internet to politically participate and engage with the government agenda. These people are part of the same element as the political activists that exist in society. Recently, several publications have questioned the effectiveness of the online community and bloggers in influencing public views. Ironically, they found that the online community and bloggers tend to spread disinformation and create more polarization. As long as these people exist, there must be non-digital methods of political participation that intertwine along the way with digital participation.

Miguel Moreno states that digital technology can harm or undermine democracy if it is controlled by too few (Anderson and Rainie 2020). He explains that there is a clear risk of bias, manipulation, abusive surveillance and authoritarian control over social networks, the internet and any uncensored citizen expression platform, by private or state actors. In some countries, there are initiatives promoted by state actors to isolate themselves from being criticized by citizens by claiming that they were acting to reduce the vulnerability of critical infrastructure to cyberattacks to the government. Indeed, this has serious democratic and civic implications. In countries with technological capacity and a highly centralized political structure, favorable conditions exist to obtain partisan advantages by limiting social contestation, freedom of expression and eroding civil rights (Anderson and Rainie 2020). In Indonesia, the government limited citizen engagement in Papua by intentionally shutting the internet down when Papuans protested massively over racism against a Papuan student studying in Surabaya, East Java in August 2020. The government tried to shut the internet down through the Ministry of Information and Informatics to reduce the turmoil caused by the mass protesters (CNN Indonesia 2020). This is an example of authoritarianism in the digital sphere. To avoid this negative consequence of increased digital democratic participation, demand for strong regulation to push against authoritarian control in digital participation is urgently needed.

4.2. Village Law Provides Access to the Public to Execute Initiatives in Local Politics

Democratization processes have been established at not only the national context but also at the local level. In the reformation era, Indonesia centered the democratic process within the national government. However, since then the center of democratic development has shifted to the local level to invite more public participation and public engagement in local provinces. The national government established a new regulation to support local governments in implementing democratic governance. This regulation is called the Village Law (UU No. 6/2014). Through this law, the government initiated a village fund program in order to accelerate poverty alleviation in the country by allocating a certain budget for every village. Since 2015, the Indonesian government has implemented the program and specifically allocated funds to every village in Indonesia. The fund is to be managed by each village in the framework of village development. As mandated by Law Number 6 of 2014, villages have the authority to manage their own resources for village development. The implementation of the Village Fund program quickly gave rise to some concrete results such as the establishment of a variety of basic infrastructure in many villages.

However, the number of cases of misuse of village funds by village heads has shown that there were serious problems with program governance and accountability. In many cases, this is due to the ineffective participation of the village community in implementing the programs. There is often no community participation at all, and even if the community participates, their inability to support the weak village governments in managing village funds properly has resulted in the ineffective implementation of programs and uncontrolled corruption. In this regard, there is a strong correlation between the level of competence and public education and the effectiveness of community participation. A better level of community knowledge will not only increase the level of community participation in the process of policymaking and the implementation of the program, but also the quality of the policies made and the results of programs that affect the community to participate more in democracy.

It is highly likely that village law alone will not be enough to facilitate public initiatives to execute direct democratic practices in local provinces. The implementation of such programs accommodated by the Village Law needs to come along with the assistance of the local government and local NGOs to reshape citizen capacity to address their needs, views, and ideas as inputs to the government and participate in local politics and the government agenda, especially in the fight against local corruption. In other words, citizen initiatives in the local context remain open, and the regulations in the Village Law have created a formal way to accommodate public participation and initiatives to their local governments.

5. Conclusion

Various literature has revealed the advantage of direct democracy in meeting public demand and achieving satisfaction by providing the means for the public to participate more directly in shaping political decisions. The most common mechanisms in direct democracy are the referendum and citizen initiatives. In this regard, referendums might be an alternative pathway to urge constitutional reform or respond to issues of major political significance.

In Indonesia’s political trajectory, the direct democracy mechanism was implemented in East Timor to allow residents to determine whether they wished to remain part of Indonesia. Unfortunately, the referendum on East Timor heated up the political instability in Indonesia. After two decades of Reformasi, there was a growing demand to reinstate referendums in order to manifest public needs to change the constitution. However, some academicians and politicians have in doubt to conduct a referendum by emphasizing the risk or its potential to threaten democratic transition. These views emerged since the rising issues to be addressed by the proposed referendums are harmful for democratic institutionalization, such as allowing the president to serve three terms instead of two. Such propositions show the potential for referendums to be a means to sustain authoritarian regimes in Indonesia’s political system. Therefore, the most feasible direct democracy mechanism to prevent democratic recession is to implement citizen initiatives at the local level by considering the Village Law and the emergence of digital technology that has created cyberspace as a new public sphere for ordinary citizens to engage with the government agenda. However, implementation of direct democracy through the accommodation of Village Law and the usage of the internet has encountered its problems. To solve these challenges, the public should be supported by local NGOs to enhance their capacity and knowledge to actively and effectively participate in democracy.

To conclude, the democratic transition in Indonesia has shown the potential for initiatives to be an effective direct democracy mechanism at the local level. This potential is supported by the Village Law and digital transformation which has allowed ordinary citizens to access information and engage with public decision making. The strengthening of direct democratic practices is thus deemed a democratic institution to ensure the functioning of civil society organizations and other interest groups to engage in policy decision making. Ultimately, these direct democratic practices have successfully bolstered Indonesia’s resilience from democratic setbacks. At the same time, there is a need to fight back to reduce the attempts to use direct democracy mechanisms as a means to promote populist policies. ■

References

Agussalim, Agussalim. 2019. “Rekonsiliasi Indonesia–Timor Leste terhadap Kes Pelanggaran Hak Asasi Manusia Pasca Referendum.” PhD diss., Universiti Utara Malaysia.

Altman, David. 2010. Direct democracy worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

______. 2015. “Measuring the Potential of Direct Democracy Around the World (1900-2014).” V-Dem Working Paper 2015: 17. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2701164

Anderson, Benedict. 1993. “Imagining ‘East Timor’.” Arena Magazine (Fitzroy, Vic) 4: 23-27.

Anderson, Janna, and Lee Rainie. 2020. “Concerns about democracy in the digital age.” Pew Research Report. February 21. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/02/21/concerns-about-democracy-in-the-digital-age/

Braithwaite, John, Hilary Charlesworth, and Adérito Soares. 2012. Networked governance of freedom and tyranny: peace in Timor-Leste. ANU Press.

Berg, Sebastian, and Jeanette Hofmann. 2021. “Digital democracy.” Internet Policy Review 10, 4. DOI: 10.14763/2021.4.1612. https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/digital-democracy

Bulmer, Elliot. 2017. “Direct democracy.” International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 3 (2017). https://aceproject.org/ero-en/the-global-passport-to-modern-direct-democracy/view

Butler, David, and Austin Ranney. 1994. Referendums around the World. Washington D. C.: American Enterprise Institute.

CNN Indonesia. 2020. “Kronologi Blokir Internet Papua Berujung Vonis untuk Jokowi.” https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20200603150311-20-509478/kronologi-blokir-internet-papua-berujung-vonis-untuk-jokowi.

Collin, Katherine. 2019. “Populist and authoritarian referendums: The role of direct democracy in democratic deconsolidation.” Brookings policy brief, Democracy and Disorder.

Crouch, Harold. 2003. “The TNI and East Timor Policy.” Out of the Ashes: Destruction and Reconstruction of East Timor: 141-167.

Dhakidae, Daniel. 2003. Cendekiawan dan kekuasaan dalam negara Orde Baru. Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

Diamond, Larry, and Leonardo Morlino. 2004. The Quality of Democracy: An Overview. Journal of Democracy 15, 4: 20-31. doi:10.1353/jod.2004.0060.

DiMaggio, Paul, Eszter Hargittai, W. Russell Neuman, and John P. Robinson. 2001. “Social Implications of the Internet.” Annual Review of Sociology 27: 307–336. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2678624.

Dutton, William (ed.). 2013. The Oxford Handbook of Internet Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 421-437.

Freedom House. 2021. “Freedom House on The Net Country Report 2021.” https://freedomhouse.org/country/indonesia/freedom-net/2021

Halperin, Morton, Joe Siegle, and Michael Weinstein. 2009. The democracy advantage: How democracies promote prosperity and peace. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Handoyo, Sri. 2014. “A Brief History of the Boundary Mapping Between Indonesia and Timor-Leste.” In History of Cartography, 165-180. Berlin: Springer.

Kosasih, Ade. 2018. “Menakar Pemilihan Umum Kepala Daerah Secara Demokratis.” Al Imarah: Jurnal Pemerintahan dan Politik Islam 2, 1.

Lake, Silverius CJM, and Frederikus Fios. 2021. “To Become Indonesian: Experience, Perception, and Hope of East Timor Refugees after Referendum (1999-2009).” BINUS Joint International Conference 2018.

LeDuc, Larry. 2020. “The politics of direct democracy.” In The Politics of Direct Democracy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Liddle, R. William. 2000. “Indonesia in 1999: Democracy restored.”

Maiwan, Mohammad. 2013. “Wacana Amandemen Kelima Undang-undang Dasar 1945 Sebagai Langkah Mewujudkan Arsitektur Konstitusi Demokratik.” Jurnal Ilmiah Mimbar Demokrasi 12, 2: 68-83. http://journal.unj.ac.id/unj/index.php/jmb/article/view/6286/4548 (in Bahasa Indonesian)

Matsusaka, John G. 2004. “Direct Democracy: New Approaches to Old Questions.” Annual Review of Political Science 14, 7: 463-482.

______. 2005. “Direct democracy works.” Journal of Economic perspectives 19, 2: 185-206.

Munhanif, Ali. 2020. “Democratization and The Politics of Conflict Resolution in Indonesia: Institutional Analysis of East Timor Referendum in 1999.” In ICSPS 2019: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Social and Political Sciences, ICSPS 2019, 12th November 2019, Jakarta, Indonesia, p. 23. European Alliance for Innovation.

Nugroho, Rahmat Muhajir, and Anom Wahyu Asmorojati. 2019. “Simultaneous Local Election in Indonesia: Is It Really More Effective and Efficient?” Jurnal Media Hukum 26, 2: 213-222.

Pereira, Celestino Boavida. 2006. “Kesepakatan tentang referendum di Timor Timur.” PhD diss., Universitas Gadjah Mada.

Pushkina, Darya, and Philip Maier. 2012. “United Nations Peacekeeping in Timor-Leste.” Civil Wars 14, 3: 324-343.

Puspita, Nina Yudhi. 2008. “Upaya United Nations Transitional Administration In East Timor (Untaet) dalam Menjaga Keamanan Perbatasan Indonesia-Timor Leste (2000-2002).” PhD diss., Universitas Airlangga.

Qvortrup, Matt. 2017. “The rise of referendums: Demystifying direct democracy.” Journal of Democracy 28, 3: 141-152.

Soares, Dionisio Babo. 2003. “Political developments leading to the referendum.” In Out of the Ashes, edited by James J. Fox and Dionisio Babo Soares, 53-73. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

Tahir, Amirullah, Syamsul Bachri, Achmad Ruslan, and Faisal Abdullah. 2015. “The Local Election and Local Politic in Emboding the Democracy.” Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization 44: 138-146.

Wike, Richard, Katie Simmons, Bruce Stokes, and Janell Fetterolf. 2017. “Globally, Broad Support for Representative and Direct Democracy.” Pew Research Report. October 16. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2017/10/16/globally-broad-support-for-representative-and-direct-democracy/

Zurbuchen, Mary Sabina, ed. 2005. Beginning to remember: The past in the Indonesian present. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

[1] Researcher at Research Center for Politics, National Research and Innovation Agency

[2] Senior Researcher at Research Center for Politics, National Research and Innovation Agency

Can Public Participation Online Strengthen Direct, Deliberative, and Participatory Democracy in India?

Kaustuv Kanti Bandyopadhyay[1]

Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA), India

Acknowledgements: This article draws on the findings of a research study titled “Institutionalizing Online Citizen Consultation for Public Policymaking in India.” The study was undertaken by Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA) with support from the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL). The author was the principal investigator for the research study.

1. Introduction

Most modern constitutional democracies govern themselves through representative forms of democracy. This representation is determined by fair, regular, and competitive elections. However, the limitations of representative democracy are well documented (Jayal 2009; Hirst 1988). To address these limitations, several innovations have been put in place by governments, civil society, and citizen associations, variously known as direct, deliberative, and participatory democracy. In spite of their common goal of complementing representative democracy, the theoretical underpinnings, trajectories, and practices for direct, deliberative, and participatory democracy, as elaborated elsewhere, are quite distinctive (Leib 2006; Carson and Elstub 2019).

Direct democracy is understood to incorporate those rules, institutions, and processes that enable the public to vote directly on proposed constitutional amendments, laws, treaties, or policy decisions. The most important forms of direct democracy are referendums and initiatives (Bulmer 2017). By contrast, deliberative democracy incorporates the participation of the public in deliberations and decision-making as a central element in democratic processes. In deliberative democracy, the public deliberation of free and equal citizens is the basis of legitimate decision-making (Joseph and Joseph 2018). In deliberative democracy, the emphasis is on deliberation, not voting, which is the focus in direct democracy. The promotion of participatory democracy exhibits a prioritization of public engagement in both formal activities, such as consultations, committee hearings, and participatory budgeting sessions, as well as in less obviously political actions such as spontaneous protests, volunteering, and in decision-making (Dacombe and Parvin 2021). Many scholars have studied, critiqued, and questioned the efficacy of direct democracy (Lupia and Matsusaka 2004), deliberative democracy (Owen and Smith 2015), and participatory democracy (Parvin 2021) in their theoretical constructs and their practical approaches.

A key expectation for a regime of democratic governance is the formulation of policies that promote equity and ensure justice. Public participation in policymaking is the cornerstone of a mature and consolidated democracy. Public policymaking that affects millions of citizens cannot rely on representative and procedural democratic mechanisms alone. It must embrace direct, deliberative, and participatory mechanisms and practices.

This paper describes the practice of public participation in the promotion of direct democracy and dives deeper into questions of potential and actual barriers to online public participation, especially with reference to policymaking. It maps existing interventions in online public participation and suggests improvements to existing approaches. After gaps in the present discourse are identified, recommendations are made to develop the most meaningful and inclusive ways to engage in public consultation online when making public laws and policies.

India, although it is the largest democracy in the world, often relies more on procedural democracy and has created very little space for direct public consultation in its national, sub-national, and local policymaking at a substantive scale. The emergence of institutions of local governance in the early 1990s has created significant spaces for public participation in decision-making related to local development. The 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendment Acts, passed in 1992, made provisions for Gram Sabhas (an assembly of all the electorates within the territory of a Gram Panchayat[2] ) and Ward Committees (made up of elected or nominated members in a municipal ward and that are to be constituted in municipalities with a population of more than 300,000). These acts broadened the functions of Gram Sabhas and Ward Committees, including participation in the planning and monitoring of all local development work. Although they form the only institutionalized space for direct participation, the experience for Gram Sabhas has been mixed. The experience of Ward Committees, for their part, has been generally disappointing, as most state governments and municipalities have not formed or activated these committees.

Over the last decade, many public programs have emphasized the importance of public participation for the effective implementation and monitoring of these programs. A few ministries and departments of both union and state governments have occasionally solicited comments, suggestions, and objections with regard to proposed policies or plans. However, in the absence of a robust mechanism and coherent laws that require mandatory public consultation, such initiatives have often been short-lived and have dissipated before they could accomplish their goals (Arora and Bandyopadhyay 2022).

In the absence of an institutionalized space for public participation in the planning and monitoring of public policy, several civil society organizations and citizen associations have used a social accountability approach and tools to promote public participation, engaging in participatory data gathering and analysis, sharing of findings with public authorities and the media, and negotiating with the public institutions responsible for the implementation of a program or policy. The civil society organizations have used many tools, including citizen report cards, community score cards, and social audits. Such initiatives have amplified citizen voices but have fallen short of institutionalization and scaling up public participation (Bandyopadhyay 2015). In cases where social audits have been institutionalized, such as in the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS), implementation has fallen far short of expectations due to the lack of alacrity on the part of public institutions and the insufficient capacity of local governance institutions.

Over the past few years, as technological innovations progressed, several governmental initiatives have leveraged technology to solicit public consultation in public policy planning and monitoring. On several occasions, ministries and departments have invited members of the public to share their concerns, comments, and suggestions regarding a specific policy or program initiative online. However, the lack of a legal framework for organizing online consultations with members of the public and affected persons in making public laws and policies undercuts the government’s efforts to place citizens at the center of policymaking. The practice of public consultation in developing public laws and policies has been sporadic, subject to whim, and inadequate. In several cases, in which suggestions, comments, and feedback have been sought from citizens on draft bills or draft rules, the government was under no obligation to close the feedback loop by disclosing specifically what feedback had been the public was considered, what was or was not included, and why this was done or not done (Arora and Bandyopadhyay 2022). However, a few civil society groups have leveraged online technology to channel public concerns and suggestions in public policymaking.

This paper pursues the following research questions: What lessons can be drawn from the online mechanisms and practices currently used by governments to consult members of the public in making laws and policies? How do civil society organizations influence policymaking using online public participation? What principles can be suggested to make online public consultations more reliable, inclusive, and ongoing?

To assess examples of governmental and civil society initiatives that promote online public participation, this paper uses a simple yet meaningful framework: Inform, Listen and Consult, Consolidate and Prioritize, and Feedback.

Inform: Communicate the details of the program or policy under consideration directly to the public. Raise public awareness and educate them about the initiative. Prepare them to engage by conveying what the institution expects from them as part of developing a program or policy and why public participation is critical.

Listen and Consult: Engage with the public by asking questions and listening to their responses. Ask specific questions to obtain quality information on the issues and ideas relevant to the program or policy under consideration.

Consolidate and Prioritize: Collect, analyze, and evaluate public responses on an ongoing basis. Different methods will require the use of different tools, but analysis will uncover important trends for various aspects of a program or policy.

Feedback: Communicate findings to the public to keep them informed. This will ensure that the public is aware of how their participation is influencing the program or policy.

2. Promise of Online Technology for Promoting Direct Democracy through Public Participation

In the last decade, as digital and information technology has developed its usefulness in all spheres of human activity, copious work is being undertaken to make development, democracy, and governance more inclusive through such technologies. Champions of a tech-driven development community often advocate the range of virtues associated with digital and information technology for promoting public participation, including:

Ease of participation–Online technology enables communication and participation between multiple actors, both state and non-state, in multiple arenas.

Scaled-up outreach despite limited resources–Constraints on the resources available to reach people collectively and en masse can be overcome with the use of online platforms. The public and other non-state actors use multiple social networking sites and online meeting platforms for communication with each other across geographies, as well as for communicating with state actors in some cases, allowing a higher degree of outreach at a larger scale.

Access to decision-makers–Multiple experiments and initiatives using online technology have provided members of the public with the ability to access decision-makers remotely, without having to encounter the bureaucratic hierarchy physically.

Integration of information from multiple ministries–Online portals have enabled the integration of information from multiple departments and ministries or across silos of domains and jurisdictions together, such that it is not necessary to spend time physically going to look for information from a certain source or to meet the exact government official in one department or another.

Artificial intelligence (AI)-based labeling and sorting for ease of analysis and decision-making–AI technology has the potential to sort and analyze a vast and diverse quantity of information using predefined labeling that otherwise would have been cumbersome and daunting to handle manually.

3. Barriers to Online Public Participation

Online public participation, especially in the Indian context, is not without limitations. The following are the most prominent barriers to scaling up online public participation.

Digital divide–The fundamental challenge for India in this area remains access to the internet and the availability of technology for all. While access and inclusivity have improved enormously in recent years, continuous, high-speed internet connectivity is still limited to pockets of the population. Many groups continue to face exclusion from access to high-speed internet access and technology, which further impacts their access to technology-based services and continues the existing gender inequality (Sheriff 2020). However, there are other chronic inequalities as well, based on intersecting factors such as income, language, literacy, disability, caste, and religion. The infrastructural challenges here include the unstable supply of electricity or power cuts in many parts of the country, poor telecom service provider signals or networks, the higher price of high-quality devices that have higher storage capacities (for which the pricing depends upon the manufacturer), and the higher price of high-speed internet broadband plans or mobile data plans (where the pricing depends on the internet service provider), among others.

Polarization of information due to predesigned algorithms–The information and news that internet users receive comes to them thanks to predesigned algorithms that provide information that is increasingly tailored to and influenced by their searches and browsing histories. This creates a cycle of polarized opinions, as a multiplicity of voices and opinions is often less tolerated and accounted for. This has contributed to a deep-seated polarization of political views and opinions among the residents of India. Thus, echo chambers or information cocoons are a growing phenomenon, in which similar views and opinions are recycled and thereby reinforced. The algorithms in play block out the diversity of perspectives.

Majority takes all–In a majoritarian democratic state and culture, there is the risk that important minority voices may be overlooked or ignored. These could be the voices of marginalized people or unpopular opinions that do not have sufficient traction or prioritization. Interactions to influence different interest groups or perspectives and facilitating a shared agenda is not easy using online consultations alone. Trust in online consultations without an offline relationship is thereby obstructed.

Untrained staff–Efforts are underway to enhance individual and organizational capacity for using technology in the functioning of governance institutions. However, these capacities vary across levels of government machinery and at present are the weakest at the district, city, and block levels. Most staff members are not trained to facilitate public participation using technology.

Sense of a safer space–Public policymaking is intrinsically political. Discussions on social media are often full of threats, trolling, and abuse, which may reduce the motivation to engage online. This poses a huge barrier to building a positive culture of participation and civic discourse. A safe space requires mutual trust and respect, especially to allow marginalized people and groups to share and communicate their vulnerabilities and lived experiences. Online modalities may not enable deep listening to alternative points of view, which is an important aspect of creating a safe space.

Obtaining relevant responses can be difficult–Promoters of public participation will likely face the challenge of receiving disparate and mixed responses based on a range of personal experiences, opinions, perceptions, evidence, and so on. This may increase the challenge of finding relevant responses. Seeking pointed and objective responses might also be subject to the biases of the institution that is seeking public participation. This is particularly relevant to the case of online responses, where opportunities to probe deeper and seek additional clarification are limited.

Extractive nature of information gathering–Information gathering exercises, even in non-digital modalities, are largely extractive in nature, such that communities and respondents are not informed how their data will be used. A similar trend is seen in digital modalities. A growing awareness of data privacy is linked to this concern.

4. Use of Technology in Public Participation–A Typology of Purposes and Mechanisms