Introduction

Although South Korea achieved economic development and democracy in a short period of time, Koreans’ evaluation of their own politics has been negative. Koreans are particularly concerned about what they perceive as a growing polarization between liberal and conservative political parties. Indeed, this perception has been verified by previous studies, which have shown that South Korea’s two major political parties are now characterized by high levels of internal ideological homogeneity and have increasingly diverged from one another over time. [1] In this way, the South Korean situation meets the definition of political polarization, which can be defined as loss of the capacity for inter-party dialogue and compromise and the recurrence of hostile confrontations and deadlock. [2]

Since roll call data were released from the second half of the 16th National Assembly, scholars have studied political polarization within the National Assembly using the Nominal Three-Step Estimation (NOMINATE) method. [3] However, this approach only measures the outcome of votes on bills, not how polarization arises and affects the legislative process in detail. We can analyze the polarization between the two camps by analyzing the speeches of political elites in the National Assembly. Politicians imbue message into language and actively utilize it in their political activities to stimulate the imagination and emotions in the service of forming an ideological or conceptual system.

Among the languages of politicians, the subcommittee meeting minutes reflect the active, competitive use of language in the legislative process because these minutes show how politicians from across the political spectrum use language to gain advantages in debates over bills. We can focus primarily on the second subcommittee of the Legislation and Judiciary Committee because it examines the wording of all bills that have been reviewed by other committees. Natural language processing (NLP) model learns the political language of 20-years’ worth of whole subcommittee meeting minutes except for the second subcommittee of the Legislation and Judiciary Committee, and it examines the minutes of the second subcommittee of the Legislation and Judiciary Committee from the 17th to 20th National Assembly. In this way, we can quantify changes in political polarization over time.

The classification model of the NLP technique using bidirectional encoder representations from the transformers (BERT) model learns sentences and words belonging to the two classes, and the trained model classifies the target text and measures its accuracy. [4] The logic of text classification is as follows. Text classification refers to the process of receiving a sentence (or word) as input and classifying where the sentence belongs between pre-trained (defined) classes. That is, in advance, by classifying the sentences or words to be learned into binary (conservative vs liberal), the NLP model learns through the learning process (training process), and the target text is input and classified. The degree of this accuracy is the result of measuring the polarization of political language.

Elite Polarization from the 17th Assembly to the 20th Assembly

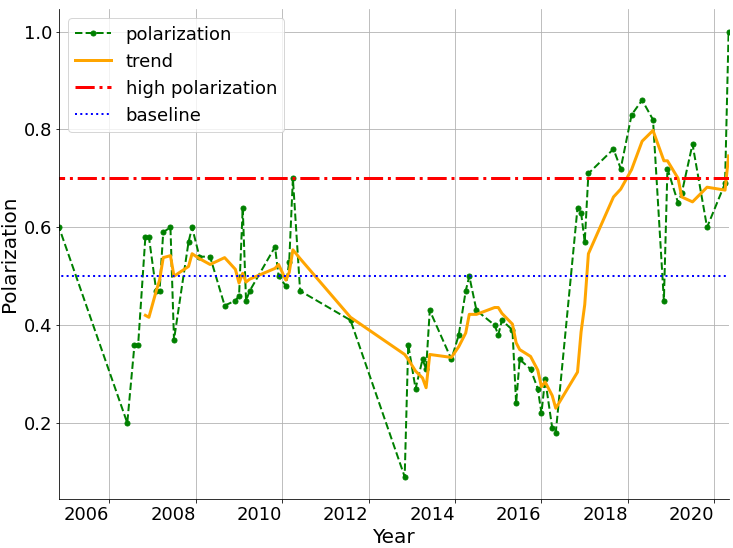

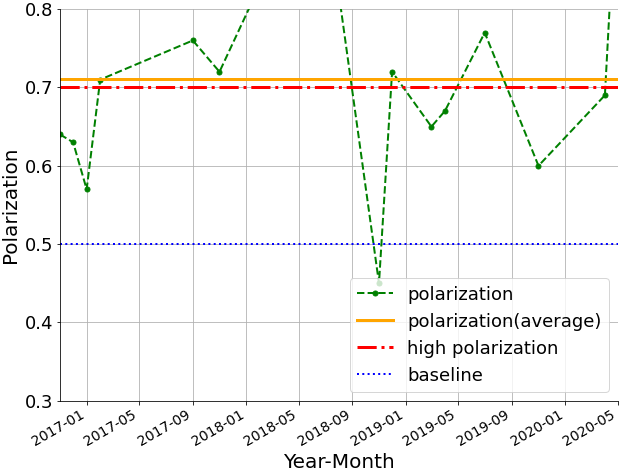

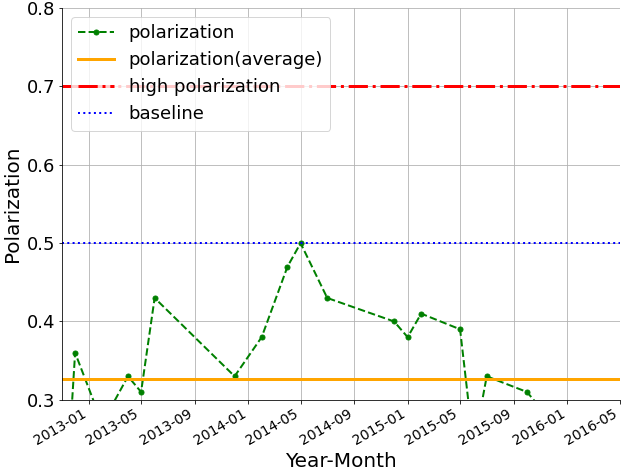

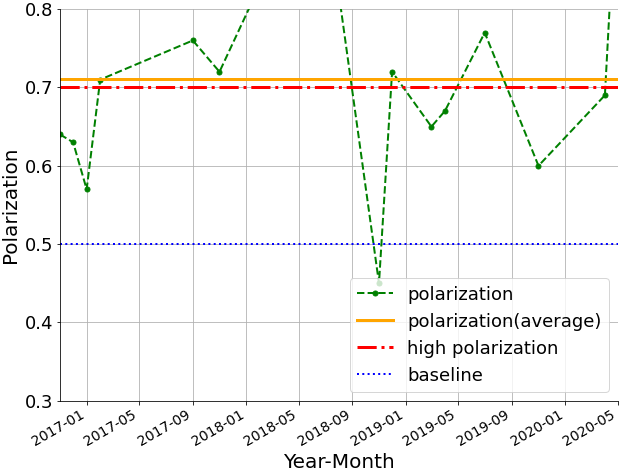

Figure 1 shows that there is a trend toward increasing political polarization. Although polarization remained relatively steady between 2004 and the early 2010s, and even decreased between 2011 and 2014, it rebounded during the first half of 2014 and has risen sharply and remained high since late 2016. This means that the more polarizing the language used in meeting minutes, the more polarized politics becomes.

.

.

Figure 1. Political polarization, 2004–2020

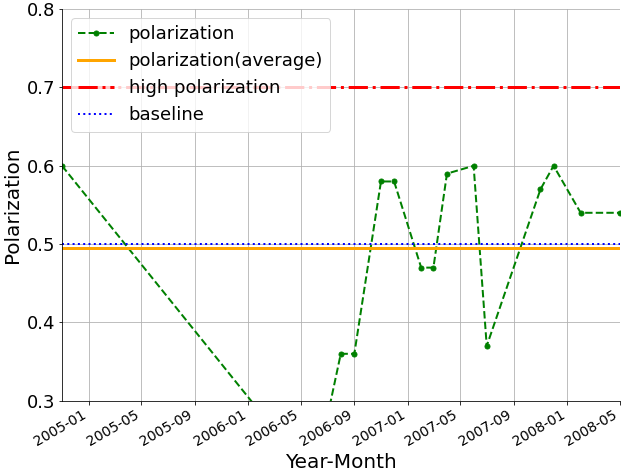

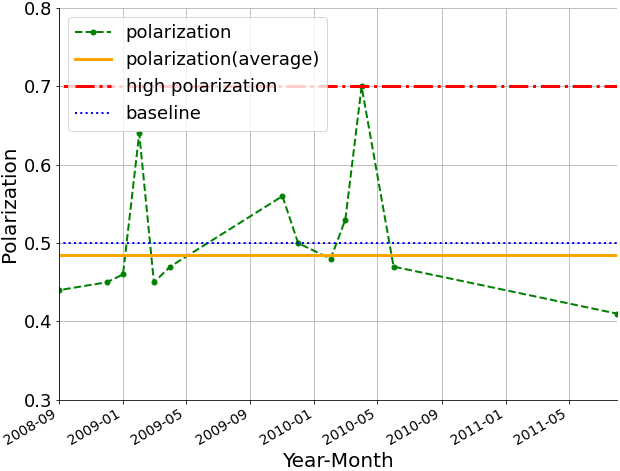

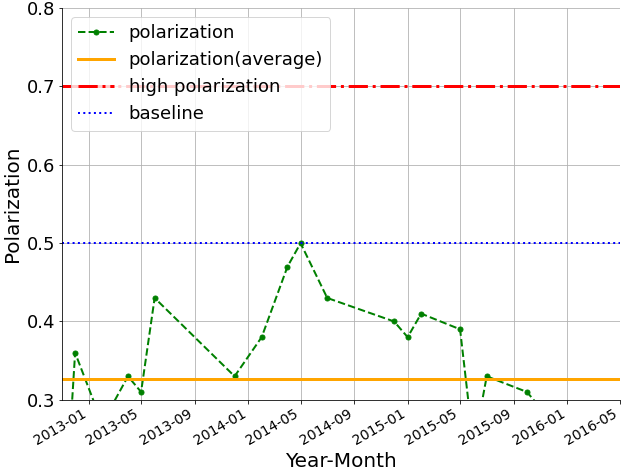

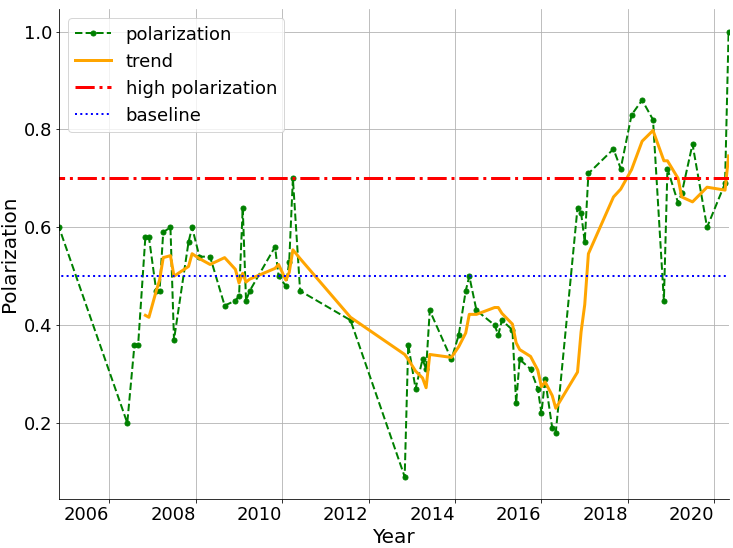

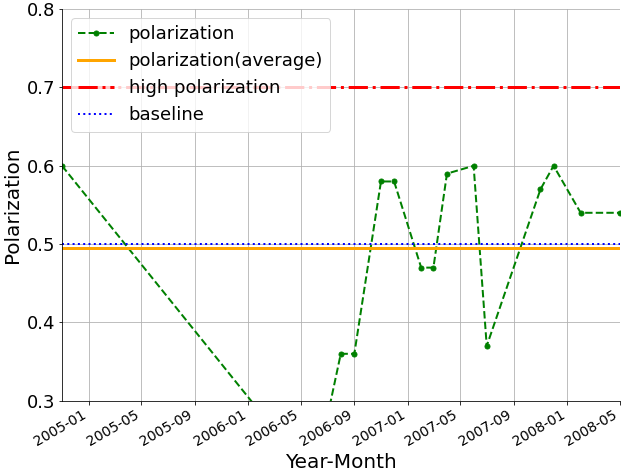

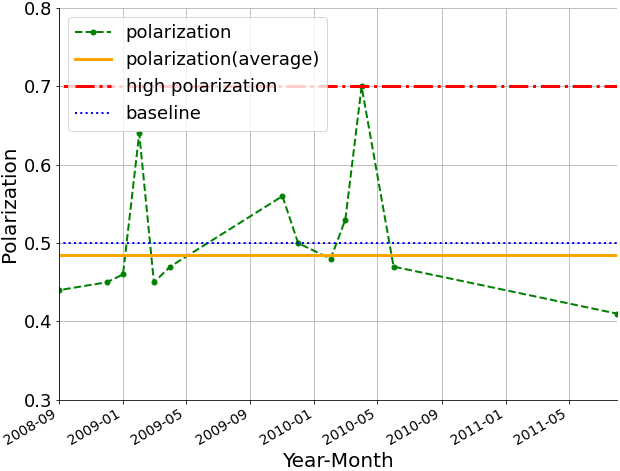

Figure 2 displays changes in political polarization between 2004 and 2020, by National Assembly. The figure indicates that the average degree of polarization was similar in the 17th (0.4953) and the 18th (0.485) National Assembly. Polarization waxed and waned during the 17th National Assembly; while it rose sharply in April of 2010, and it then trended downward for the rest of the 18th National Assembly. The average degree of polarization during the 19th National Assembly was 0.3265; it rose during April and May of 2014 and then began to decline. Polarization was most severe during the 20th National Assembly, in which the average degree of polarization was 0.7043. The data indicate that polarization rapidly escalated in February and March 2009, April 2010, June 2013, May 2014, and November 2016. Although it usually decreased after these escalations, polarization has remained very high since 2016.

|

(a) 17th National Assembly (2004–2008)

|

(b) 18th National Assembly (2008–2012)

|

|

|

|

|

(c) 19th National Assembly (2012–2016)

|

(d) 20th National Assembly (2016–2020)

|

|

|

|

Figure 2. Political polarization, 2004–2020, by National Assembly

From a data-intuitive perspective, the rise and fall may be attributed to the noise in the data. However, remaining high should be interpreted in a different context. This finding implies that polarization is becoming more intense over time rather than returning to normal or exhibiting the wax and wane pattern of previous National Assemblies. Given that this model captures wider political differences beyond particular legislation, this study interprets pre-2016 cycles in polarization as reflecting regular politics and debate. It also considers the high level of post-2016 polarization as a growth of a more enduring set of ideological differences between ruling and opposing parties.

There may be several reasons behind the post-2016 polarization increase, but the impeachment of President Park undeniably looms the largest among them. After President Moon Jae-in was elected following the impeachment, his administration promoted investigations which framed the previous two conservative administrations (Park Geun-hye administration and Lee Myung-bak administration) as corrupt and untrustworthy. These included the creation of a special committee to confiscate the illegitimate proceeds earned by former president Park Geun-hye. The Moon Jae-in administration’s core and public focus on correcting the mistakes and injustices of previous governments formed by the opposition party has had a lingering and polarizing effect on Korean political discourse. Although these policies nominally aimed to restore and improve South Korean democracy, they have instead made Korean politics so polarized that party politics became nearly impossible. There have been no joint efforts between the two parties to create an inclusive, good-faith, post-impeachment regime in the public interest, and this has led to a culture of slander and personal attacks.

Unfortunately, the politicians who made up a large part of the conservative party opposed or denied the impeachment, and ironically disparaged and rejected the democratically constituted Moon Jae-in administration. On the other hand, the faction that led the impeachment regarded the opposition faction only as an object of reform and did not accept it as an object of cooperation, driving parliamentary politics into a hostile confrontation. Following the impeachment, Park’s party – the People’s Power Party – conducted political activities outside of parliament, such as the Taegeukgi street rallies. These rallies turned violent and, in turn, damaged the legislative process and the prospect for effective parliamentary politics. Conflicts between two factions persisted throughout the 20th National Assembly, and the findings above can be interpreted as reflecting the language of conflict in the process of legislation.

Implications

The findings demonstrate that political polarization in South Korea has been fluctuating since the 17th National Assembly. Polarization in South Korean society is not a recent phenomenon; however, as of the second half of 2016, political polarization rose sharply, and has remained high throughout the 20th National Assembly.

Political polarization (elite polarization) presents important implications regarding the role of the legislature. A certain level of tension between political parties according to the ideological position is a natural phenomenon in modern politics and is also necessary for better policy formulation. However, if political polarization is extreme and persists for a long period of time, it would have a negative impact on the society as a whole. Under extreme political polarization, compromise becomes difficult because the polarized political language, or political polarization itself, will nearly eradicate the common ground among options favored by each political faction. As a result, bills closely related to the lives of the citizens bearing little ideological nature (bills for people’s livelihood) may not be properly reviewed, with the possibility of deadlock in the process of legislative deliberation and last-resort negotiation. As a result, the quantity and quality of bills passed may decrease, adversely affecting people’s lives. Indeed, the 20th National Assembly has had the lowest bill passage rate of any National Assembly, at approximately 36%. Furthermore, political polarization could undermine other important functions of the National Assembly, such as confirmation hearings.

Above all, the polarization of elite politics reduces the scope of consensus between the opposing factions , making it difficult to legislate policies that the majority of the society can support. As a result, each political faction maintains a policy geared only toward its supporters, which could divide society as a whole and cause political polarization across society. In a polarized political environment, citizens tend to view their society as characterized by a dichotomy of good and evil and regard others as enemies to overthrow rather than partners for coexistence. Political polarization throughout society will in turn intensify the polarization of elite politics, resulting in a vicious cycle of political polarization.

Can we change the trend of deepening elite polarization in Korean politics and restore the politics of dialogue and compromise? If political leadership plays a role, politics of dialogue and coexistence would be possible. It is more necessary than ever to reform the party system and lead dialogue and communication in order to overcome elite polarization and restore productive politics. As formerly stated, politicians imbue meaning into language and actively utilize it in their political activities to stimulate the imagination and emotions in the service of forming an ideological or conceptual system. Therefore, political polarization can be alleviated through more dialogue between parties. ■

[1] Ka, Sang Joon (가상준). 2014. “한국국회는 양극화되고 있는가?” [Has the Korean National Assembly been polarized?] 의정논총 [Journal of Parliamentary Research] 9 (2): 247–272; Park, Yun-Hee, Min-Su Kim, Won-ho Park, Shin-Goo Kang, and Bon Sang Koo (박윤희 김민수 박원호 강신구 구본상). 2016. “제20대 국회의원선거 당선자 및 후보자의 이념성향과 정책태도” [Ideology and Policy Positions of the Candidates and the Elects in the 20th Korean National Assembly Election]. 의정연구 [Korea Journal of Legislative Studies] 22 (3): 117–158.

[2] McCarty, Nolan, Keith T. Poole, and Howard Rosenthal. 2006. Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches. Cambridge: MIT Press.

[3] Poole, Keith T., and Howard Rosenthal. 1985. “A Spatial Model for Legislative Roll Call Analysis.” American Journal of Political Science 29 (2): 357–384; Jeon, Jin-Young (전진영). 2006. “국회의원의 갈등적 투표행태 분석: 제16대 국회 전자표결을 중심으로” [A Study of Members’ Conflictual Voting Behavior in the 16th Korean National Assembly]. 한국정치학회보 [Korean Political Science Review] 40 (1): 47–70.; Lee, Kap-Yun, and Hyeon-Woo Lee (이갑윤 이현우). 2008. “이념투표의 영향력 분석: 이념의 구성, 측정 그리고 의미” [A Study of Influence of Ideological Voting: Scope, Measurement and Meaning of Ideology]. 현대정치연구 [Journal of Contemporary Politics] 1 (1): 137–166.; Lee, Nae Young, and Hojun Lee. 2015. “Party Polarization in the South Korea National Assembly: An Analysis of Roll-Call Votes in the 16–18th National Assembly.” Journal of Parliamentary Research 10 (2): 25–54.;

[4] Devlin, Jacob, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. “BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding.” Proceedings of the NAACL-HLT 2019, June 2–7, 2019, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

■ Seungwoo Han is a Adjunct Lecturer at the Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey and a Consultant at the Social Protection & Jobs Global Practice World Bank.

■ Typeset by Jinkyung Baek Senior Researcher

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 209) | j.baek@eai.or.kr

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Elite Polarization in South Korea: Evidence from a Natural Language Processing Model](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2022101213540630141651.png)

.

.

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20240419123938102197065(1).jpg)

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2024032815145548472837(1).jpg)