![[ADRN Working Paper] Horizontal Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅰ)](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20240305162413775004648.jpg)

[ADRN Working Paper] Horizontal Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅰ)

| Working Paper | 2024-03-05

Asia Democracy Research Network

Checks and balances between state institutions are crucial for holding the government accountable, and preventing executive aggrandizement and corruption. Recognizing the significance of horizontal accountability in achieving robust and sustainable democracy, the Asia Democracy Research Network (ADRN) has conducted research to evaluate the current trends and trajectories of horizontal accountability in the region, as well as proposing key reforms for the future. As part of this research, EAI launched a working paper series comprising seven final reports, covering the cases of Indonesia, Mongolia, Pakistan, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, and Thailand.

In 2022, Asia Democracy Research Network (ADRN) selected horizontal accountability by the ability of state institutions to hold the executive branch accountable, and vertical accountability through elections, parties and citizens’ participation, as the requirements to accomplish robust and sustainable democracy in Asia.

Against this background, ADRN published this report to evaluate the current state of the trends and trajectories of horizontal accountability in the region by studying the phenomenon and its impact within countries in Asia, as well as their key reforms in the near future.

The report investigates contemporary questions such as:

● What are the constitutional and legal institutional mechanisms that hold the executive government accountable?

● To what extent have the constitutional and legal mechanisms of horizontal accountability fulfilled their expected functions to constrain the actions of the executive members?

● What are the determinants of horizontal accountability performance?

● What should be done to improve the state of horizontal accountability performance?

Drawing on a rich array of resources and data, this report offers country-specific analyses, highlights areas of improvement, and suggests policy recommendations to fulfill methods of horizontal accountability in their own countries and the larger Asia region.

Horizontal Accountability in Indonesia

Devi Darmawan[1], Sri Nuryanti[2]

National Research and Innovation Agency

1. Introduction

As a new democratic country of the third-wave democratization, it is compelling to observe the performance of Indonesia’s government in sustaining horizontal accountability, especially after amending the constitution. In the early reformation era, Indonesia inserted the checks and balances principles into the Constitution in order to generate horizontal accountability between executive, legislative, and judicial power. Therefore, the constitution is also critical to measure the configuration of the horizontal accountability mechanisms by highlighting the constitutional executive, legislative, and judicial powers.

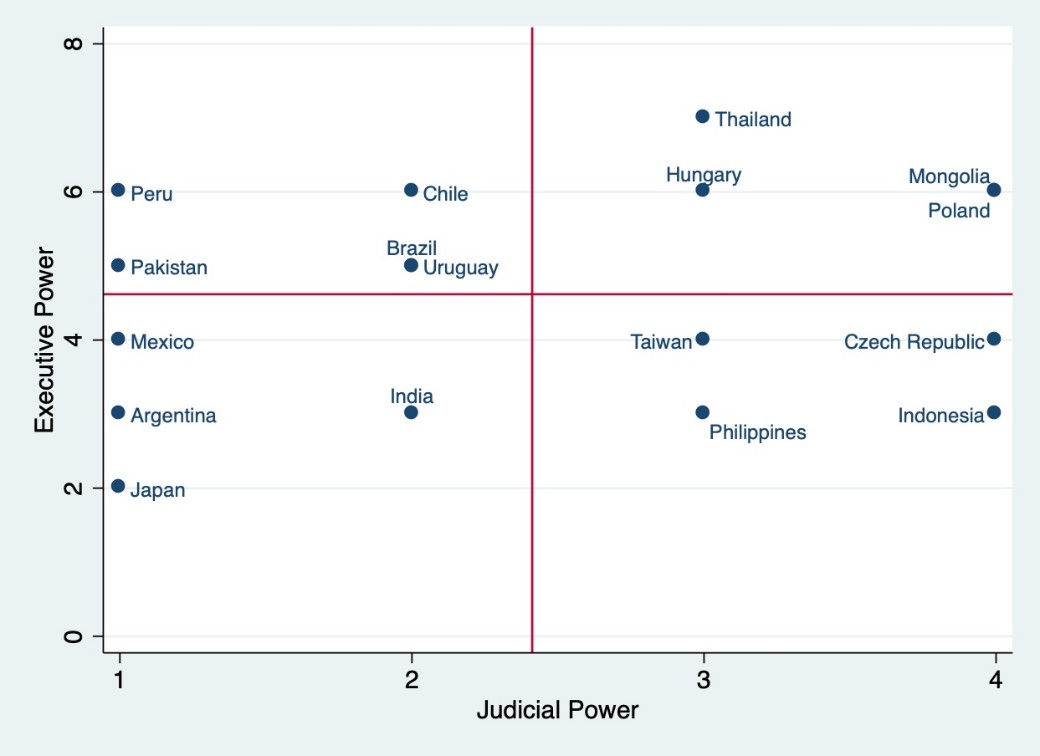

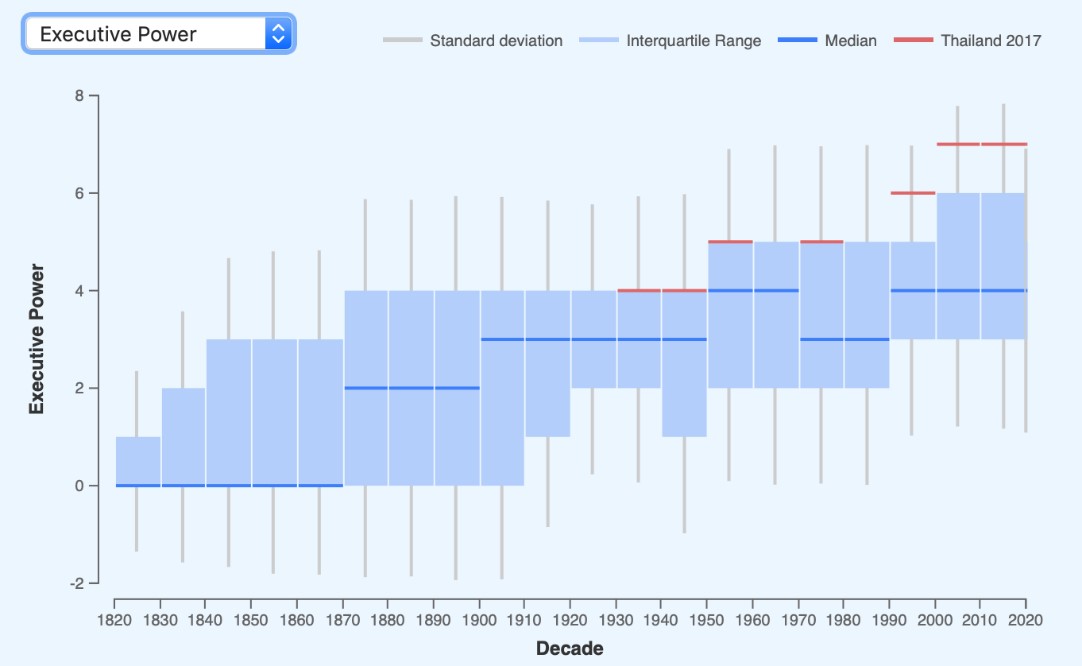

There are a variety of empirical indicators to measure executive, legislative, and judicial powers in order to describe Indonesia’s de jure horizontal accountability. First, for executive power or constitutional endowments of executive actions, we utilized the ‘executive power index’ from Constitute, which ranges from 0 to 7 and captures the presence or absence of seven significant aspects of executive law-making: (1) the power to initiate legislation; (2) the power to issue decrees; (3) the power to initiate constitutional amendments; (4) the power to declare states of emergency; (5) veto power; (6) the power to challenge the constitutionality of legislation; and (7) the power to dissolve the legislature. The index score is the mean of the seven binary elements, with higher numbers indicating more executive power and lower numbers indicating less executive power (Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton 2023). Based on the data provided by Constitute, Indonesia’s executive power index score is 4, which reflects its constitutional provisions of (1) the power to initiate legislation,[3] (2) the power to initiate constitutional amendments,[4] (3) the power to declare states of emergency;[5] and (4) veto power.[6]

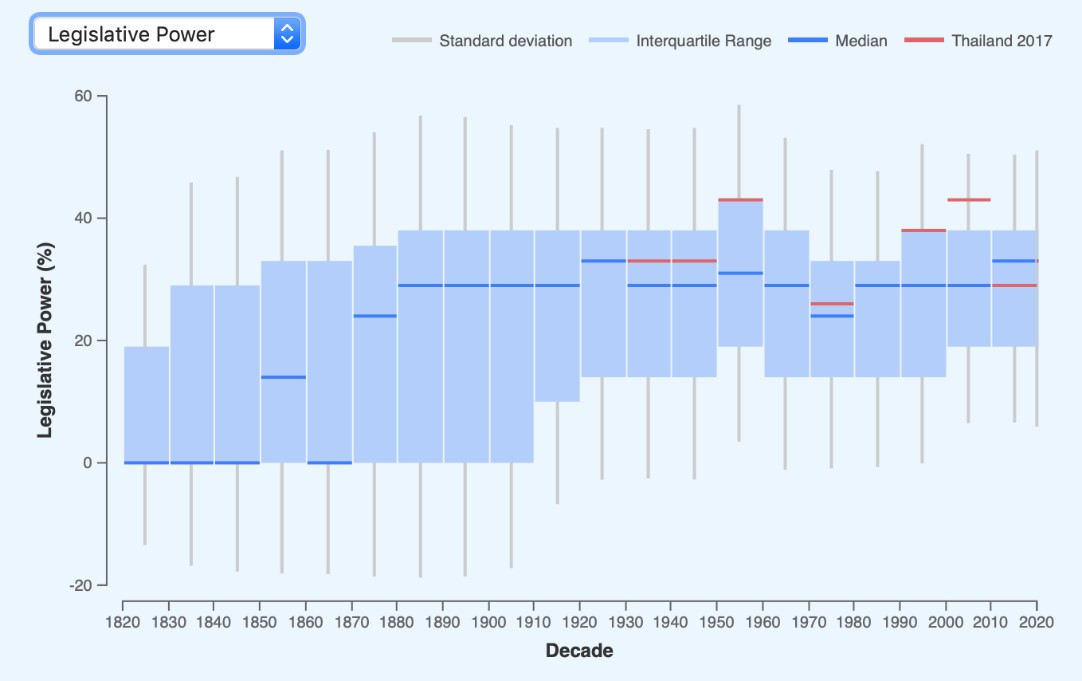

Second, for legislative power, the measurement used the data legislative power index provided from a survey developed by M. Steven Fish and Mathew Kroenig in The Handbook of National Legislatures: A Global Survey (Cambridge University Press, 2009), which ranges from zero (least powerful) to one (most powerful) to reflects a legislature’s aggregate strength. The index score is simply the mean of the following thirty-two binary elements, with four main focuses (influence over executive, institutional autonomy, specified powers, and institutional capacity). Thus, the total accumulation with higher numbers indicating more legislative power and lower numbers indicating less legislative power (Fish and Kroenig 2009). Based on the survey result conducted in 2006-2007, Indonesia’s legislatures power score is 0.56, which means legislative power in Indonesian presidential democracy is still influential despite the overpowering presidency.

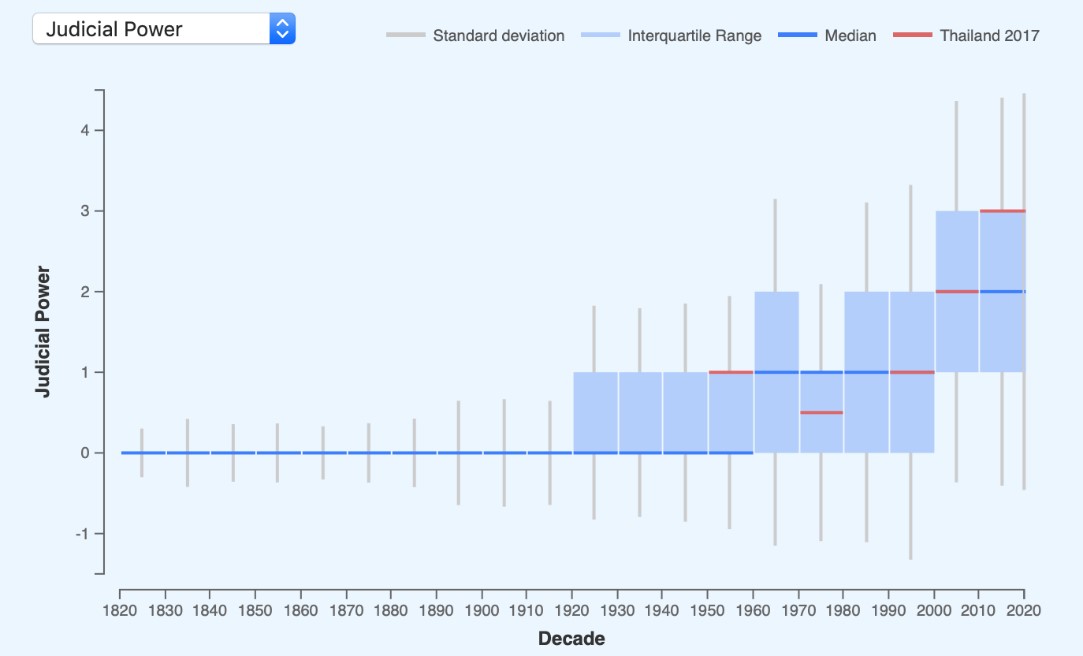

Third, for judicial power, the data to measure utilized the “judicial power index” from Constitute which ranges from 0 to 6 and captures the presence or absence of features of judicial power. There are six features to construct the score, including (1) whether the constitution provides for judicial review; (2) whether courts have the power to supervise elections; (3) whether any court has the power to declare political parties unconstitutional; (4) whether judges play a role in removing the executive, for example in impeachment; (5) whether any court has any ability to review declarations of emergency; and (6) whether any court has the power to review treaties. Based on Indonesian Constitutions, the score of judicial power rest in 1 point that is the judicial ability to remove the executives mentioning in the feature number (4) whether judges play a role in removing the executive, for example in impeachment.[7] This score of judicial power showed that the judiciary has less power to constraint on executive actions.

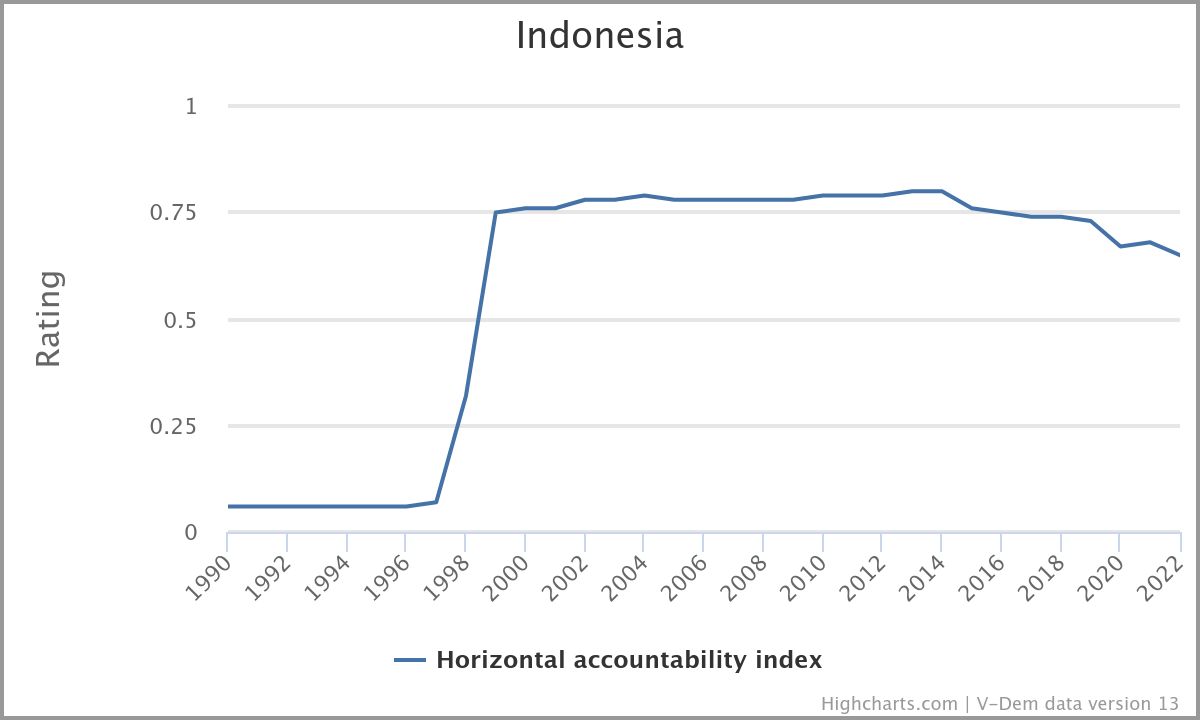

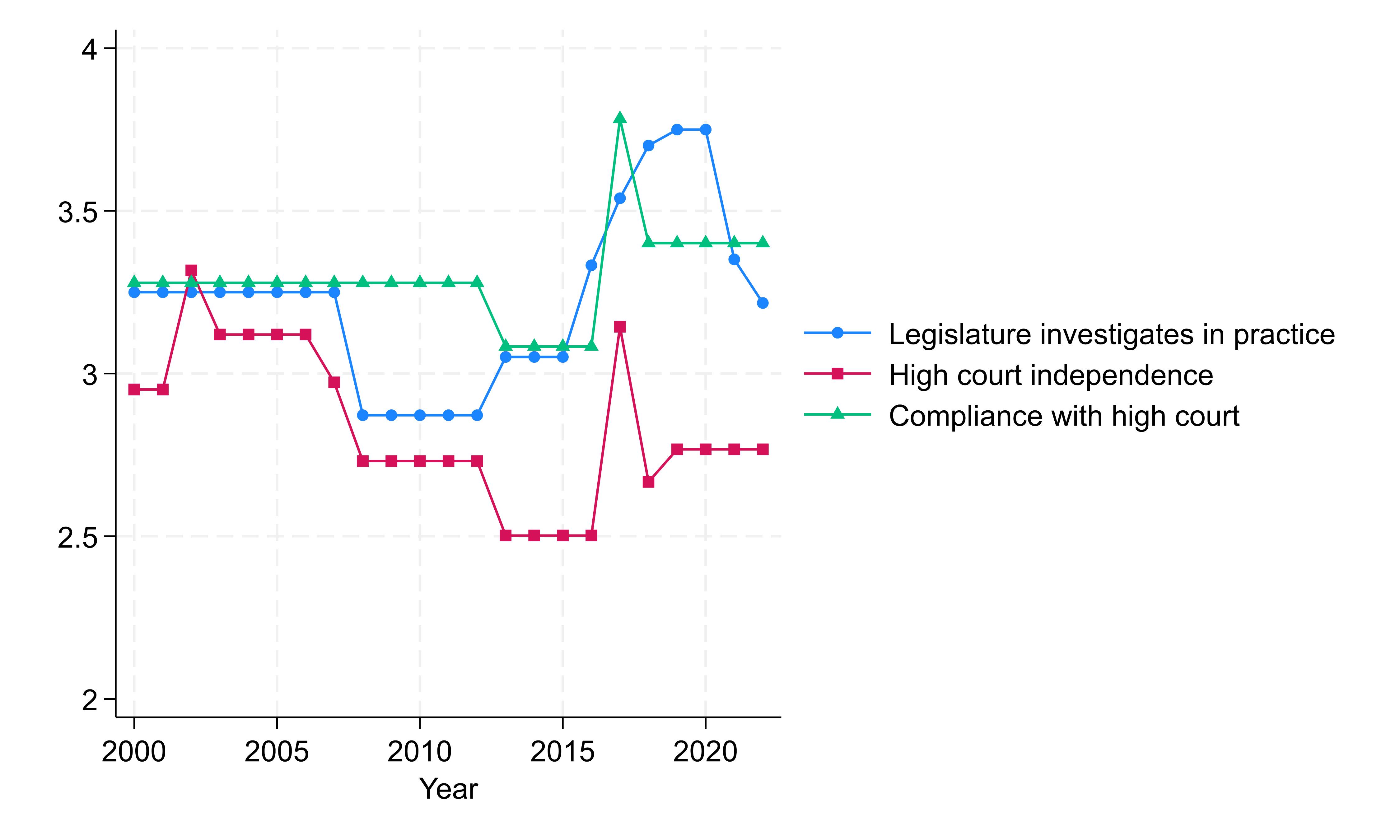

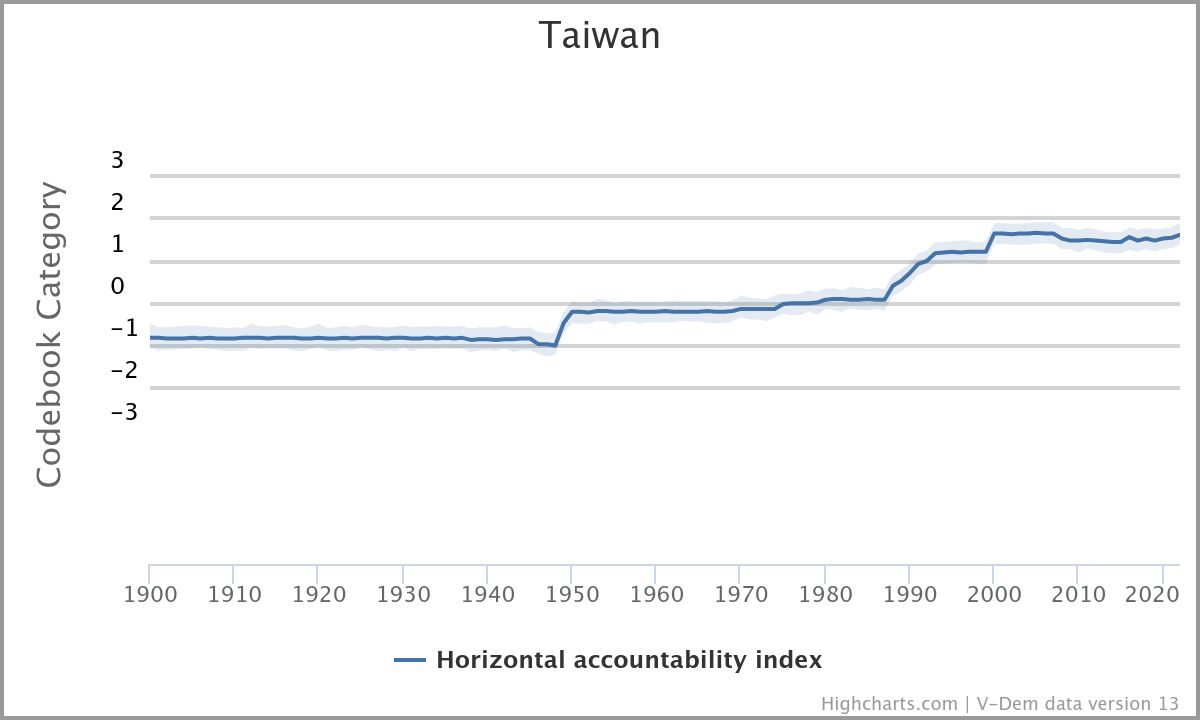

Unfortunately, two decades after reformation, the horizontal accountability has slightly decreased. Based on V-Dem datasets on horizontal accountability index,[8] the graphic shows that the horizontal accountability rate rose around the year 2000 in time when the reformation took place and the new phase of democratization started. However, it slightly decreased in recent years.

Figure 1. V-Dem Horizontal Accountability Index: Indonesia 1990-2022

This trend of decreasing horizontal accountability index signaled the problem of implementing horizontal accountability and checks and balances mechanisms to prevent the wrongdoing of public officials. If the trend persists, the decreasing horizontal accountability will be followed by the same decrease in other accountabilities both vertical and diagonal which all simultaneously will cause the democratic decay from within (Sato et al. 2022). It means that election and other public participation toward government will no longer be meaningful to progressing democratization when horizontal accountability is in absence.

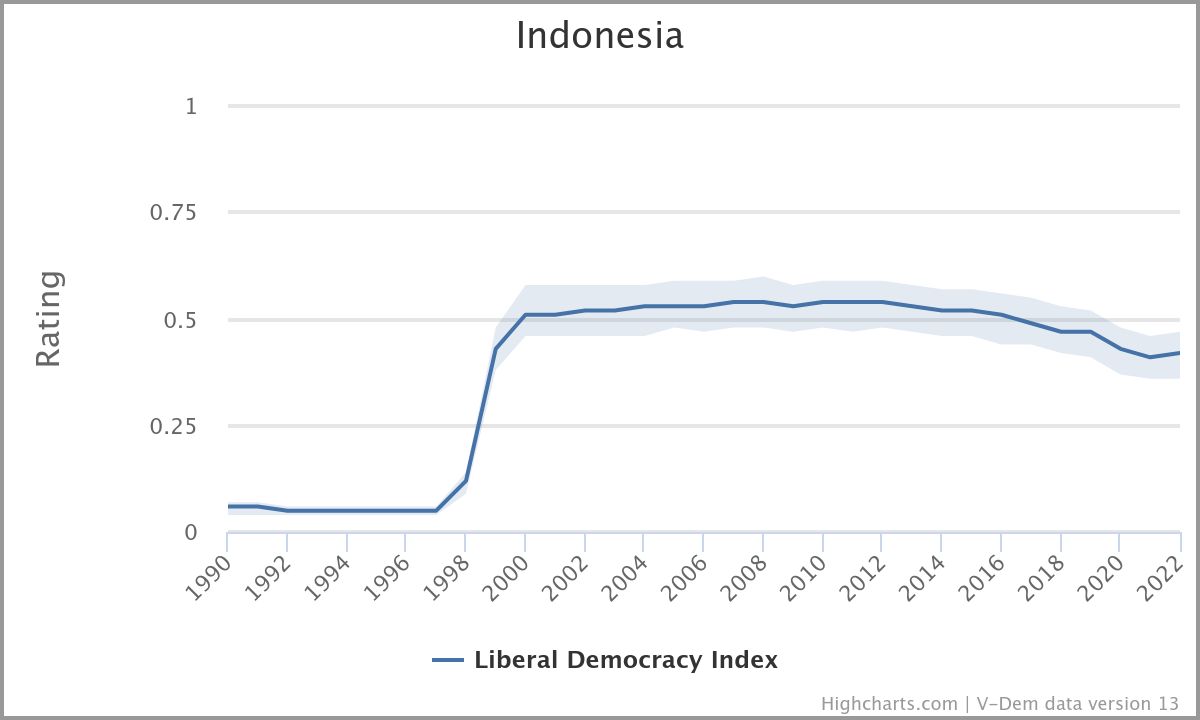

The influence of the horizontal accountability deficit in Indonesia could explain the reason why Indonesia experiences democratic decline. This argument is confirmed by the data of the democracy index provided by Freedom House. According to Freedom house, Indonesia has made impressive democratic gains since the fall of an authoritarian regime in 1998. However, the democratic index shows the decreasing progress of Indonesian democracy. Recent update from Freedom House in 2022 states that Indonesia democracy index remains partly free with the score range 59/100 (no longer free). Roylance (2015) argued that once a country achieves the status of Free, it should be solid and reliable to combat backsliding to authoritarian states and advancing progress to implement good governance with accountability. Unfortunately, the case of Indonesia shows an incremental process in sustaining democratization caused by the absence of checks and balances among state branches as democratic institutions. Further, V-Dem stated that Indonesia’s score has decreased over the past 10 years substantively and at a statistically significant level as illustrated in the liberal democracy index (LDI) 2022 below.

Figure 2. V-Dem Liberal Democracy Index: Indonesia 1990-2022

Based on the graphic above, the symptom of democratic decline in Indonesia seems to be influenced by the horizontal accountability deficit. Despite being commendable for successfully holding regular elections at both the national and local levels, the progress of democratic transition in Indonesia appears less promising due to the lack of horizontal accountability. The failure to sustain horizontal accountability may lead to democratic setbacks where state institutions could become corrupt and violate democratic principles. Consequently, the absence of horizontal accountability would leave unmeaningful elections as the only remaining institution representing democratic countries. Considering Indonesia’s democratic practices, the efforts to apply horizontal accountability and achieve the principle of checks and balances among state branches remain problematic due to the unequal power to hold the president accountable. This condition needs to be critically examined, specifically to assess the ability of the new democratic government to perform its checks and balances amongst state institutions.

The research about the checks and balances to manifest horizontal accountability is particularly relevant nowadays, as Indonesia is experiencing democratic stagnation and the weak function of its checks and balances mechanism. Democratic scholars have argued that the state of democracy should institutionalize the checks and balances principles to push back against backsliding into authoritarian regimes in order to preserve democratic consolidation. Otherwise, democratization could remain stagnant, distinguished by the domination of the elite shadowing the democratic process within Indonesia’s political stage. Considering this condition as background, this paper aims to explain about the embodiment of horizontal accountability in Indonesia and the gap between the rules and the practices of sustaining checks and balances toward the president as head of executives.

2. The Discourse of Horizontal Accountability’s Conceptualization

The presence of accountability determined the quality of democracy and the effectiveness of the governance. Although consensus about accountability definition is hardly to be sustained among scholars, conceptually, accountability has two key features, that are answerability and responsibility of public officials. Within this conception, there are two kinds of actors who can provide political accountability. First, elected public officials are accountable to voters. Second, many state agencies are formally charged with overseeing and/or sanctioning public officials and bureaucracies. The first is about vertical accountability, and the latter is about horizontal accountability, or as Mainwaring called it, intrastate accountability. In democratic countries, horizontal accountability tends to be more fragile than its vertical counterpart since authoritarian institutional virtues are more challenging to transform than organizing free and fair elections (De Almeida Lopes Fernandes et al. 2020). Nowadays, embodiment of horizontal accountability in some democratic states remains problematic (O’Donnel 1998).

Horizontal accountability is necessary to prevent corruption and improper state encroachment because conceptually horizontal accountability refers to actions “with the explicit purpose of preventing, cancelling, redressing and/or punishing actions (or eventually non-actions) by another state agency that are deemed unlawful, whether on grounds of encroachment or of corruption” (O’Donnell 2003, p. 35). In the same line, Ziegenhain (2015) explained further about horizontal accountability that refers to the capacity of governmental institutions to check abuses by other public agencies and branches of government. In addition, other independent state agencies, which control and scrutinize government actions, are also often necessary to safeguard horizontal accountability. These institutions working as agencies of restraint, such as independent electoral commissions, auditing agencies, anti-corruption bodies, and ombudsmen, also contribute to horizontal accountability (Ziegenhain 2015). Therefore, the existence of such institutions is a key for establishing accountability.

The relation of accountability in democratic states consists of the checks and balances mechanism that derives from the interaction between the institutions mentioned above. However, the list of institutions that acted as actors of accountability varied between parliamentary democracy and presidential democracy. The actors of accountability are determined by the principal-agent relationship wherein the voters play as principal, and the public official as agent who was elected through legitimate election. The fundamental difference between presidential and parliamentary democracies is that the hierarchical connection between voter-principals and the executive authority is not mediated through the legislative majority in a presidential systеm as it is in a parliamentary systеm. That is, whereas parliamentary democracies are based principally on nested hierarchies of vertical accountability, presidential systеms are built on the interaction of horizontal exchange and vertical accountability. This fundamental distinction has serious consequences for legislative incentives in presidential systеms (Shugart and Haggard 2001), and, in turn, for how well horizontal accountability functions to align the incentives of actors in the various branches with the interests of the ultimate principal, the citizenry.

As a presidential democratic country, the horizontal accountability in Indonesia is exercised only by state actors within the state by different state agencies, if necessary, against the president as the highest powers of the state to prevent any legal transgression. Most scholars argued that the relationship between state institutions and oversight bodies is crucial to the functioning of a systеm of horizontal accountability. Therefore, the exercise of horizontal accountability specifically rests on the performance of the elected public officials from the executive and the legislative branch since both of them had acquired mandates from the voters to execute their authorities. Thus, the other state actors such as Judicial court, Ombudsman, Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) will be the oversight agency that hold responsibility to request explanation and sanction the president and member of parliament as elected public officials for their acts and omissions in accordance with the law and constitution.

Unfortunately, horizontal accountability faces a challenge from within state actors by a scourge of “the accountability trap.” Slater accused this condition occurs due to exerting cartel politics to secure the power sharing among political parties (Slater 2004). Moreover, cartel politics, perpetrated by the absence of an opposition party in the government, hampers a dynamic equilibrium between major state actors, which is important for horizontal accountability. Horizontal accountability will never function properly if one actor can dominate the others, indicating that the democratic regime is in danger of becoming unconsolidated and prone to authoritarian rule. Without effective institutions that can provide credible restraints in presidential democracy, particularly on powerful executives, the quality of democracy tends to stagnate or regress.

3. The Constitutional and Legal Institutional Mechanisms of Horizontal Accountability

With reference to the conceptualization of horizontal accountability, the agent of accountability in presidential democracy is not only president, but also member of parliament because both of them are elected officials and hold the mandates from the voters. However, the exercise of horizontal accountability delimits its scope only to the highest authority in presidential democracy, president, as the head of states and governance. Indonesia has institutionalized the horizontal accountability mechanism to hold the president responsible for his/her performance that was written in the constitution and regulated among various acts, to prevent president from legal violations. There are two important dimensions to establish a horizontal accountability mechanism: the answerability and sanctions. Firstly, the accountability of the president is ensured through the oversight of members of parliament (state legislature), as outlined in article 20a of the constitution. Therefore, the state legislature has the right to ask and demand an explanation on a particular case or public policies made by the president to redress the possible wrongdoings. Secondly, there are provisions for sanctions when the president is accused of violating the law. According to the Indonesian Constitution, specifically UUD 1945, sanctions are outlined in cases where the president commits legal transgressions such as corruption and bribery. The sanction ranged from providing explanation and the possibility of removal from the office or impeachment as it mentions in article 7a, 7b, and 7c of UUC 1945. This impeachment process involves the roles of state legislature and Constitutional Court (MK).

As described above, O’Donnell defined horizontal accountability as “the existence of state agencies that are legally enabled and empowered, and factually willing and able, to take actions that span from routine oversight to criminal sanctions or impeachment in relation to actions or omissions by other agents or agencies of the state that may be qualified as unlawful.” Thus, the list of state actors who can execute relationship of accountability toward president includes not only the state actors that have sanctioning capacity of judicial branch, but also the oversight agencies without necessarily having capacity to impose sanctions but expected to refer possible wrongdoings to actors that can impose sanctions; this indirect sanctioning power suffices to characterize a relationship of accountability, such as ombudsman and commission of eradication corruption (KPK). In this regard, the state actors that can establish accountability relations toward the president include the oversight state agencies and also the highest court from the judiciary branch to monitor the president in performing his/her power. Further, the oversight state agencies comprehend KPK and Ombudsman whereas the judiciary branch comprises MK and MA. All of these listed state actors are regulated by particular national acts to establish accountability relationships to check the president accountable.

3.1. State Legislatures (member of parliaments)

The Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia has established the President as the holder of executive power and the People’s Representative Council (DPR) as the holder of legislative power. The president’s authority is contained in Article 4 paragraph (1) of the 1945 Constitution while the DPR authority can be found in Article 20 paragraph (1) of the 1945 Constitution which states clearly that the power to make laws is in the hands of the DPR. In addition, the Article 20 paragraph (2) of the 1945 Constitution shows the relation between DPR and the president in legislation especially in the president involvement in drafting laws and regulations and also in giving joint approval with the DPR on the bill that has been discussed.

In addition to the lawmaking process, relations between the president and the DPR can also be seen in the process of forming Government Regulations in Lieu of Laws (Perpu). Government Regulations in Lieu of Laws (Perpu) are regulations made by the President in “forced matters of urgency”, therefore the process of their formulation is different from that of laws. Generally, laws have always been formed by the President with the approval of the House of Representatives or formed by the House of Representatives and jointly approved by the House of Representatives and the President. However, the Government Regulations in Lieu of Laws (Perpu) are formed by the President without the approval of the People’s Representative Council because of a “compelling urgency” that requires fast-track of the lawmaking process to overcome the pressing crisis.

If the Government Regulation in Lieu of Law is approved by the DPR in a plenary session, it shall be stipulated to become an Act. On the contrary, if the Government Regulation in Lieu of Law does not obtain the approval of the DPR in a plenary meeting, it must be revoked and declared null and void followed by action from the DPR or the President submitting a Draft Law on Revocation of Government Regulations in lieu of law. Based on these schemes, the relation between president and DPR can be seen within the legislation process. Although both the president and DPR have legitimate delegation from voters as the principals of accountability, their relationship portrayed the checks and balances that constitutes the horizontal accountability in the legislative process. Regardless that the legislature does not have capacity to impose sanctions, the constitution gives the right to DPR to demand answerability from the President in case there is accusation of legal transgressions committed by the President. Moreover, DPR can continue to request the Constitutional Court to conduct an examination toward the President as part of impeachment procedure or ask other state agencies such as Indonesian Republic Attorney General, Commission of Eradication Commission to execute law enforcement and give sanction in case the President is involved in any legal transgression.

3.2. Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK)

The Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) has been institutionalized since 2002, not long after reformation took place. KPK has the authority to monitor the adm?nistration of state government, supervise state agencies authorized to carry out the eradication of criminal acts of corruption. Based on its authority, KPK has not acquired direct sanctioning capacity to impose President or other public officials, but it can supervise and investigate the allegations of corruption and took the rest to the court to proceed the judicial process. In general, KPK can investigate all state actors if they were suspected of corruption. However, in recent years, KPK has been weakened by the government through the revision of its institutional position. Since the law of KPK No. 30/2002 has been revised by emerging the new Law in 19/2019, the KPK has no longer be independent institution, but being responsible to President as the head of executives. Consequently, KPK would hardly be possible to investigate any corruption case that potentially carried out by the president. In the context of sustaining horizontal accountability, the position of KPK has changed from the state actors that can monitor all legal transgressions toward president or member of parliament or any state actors to become the agents of accountability itself. KPK had been chosen by the president and by this means that president is the principal who can demand the answerability and give sanction to KPK. In other words, KPK can only touch the member of parliament and control the wrongdoing of state legislatures.

3.3. Ombudsman of the Republic of Indonesia

The Indonesian Ombudsman is a state institution that has the authority to supervise the implementation of public services whose funds come from the State Budget (APBN) or Local Government Budget (APBD). Institutionally, the formation of the Indonesian Ombudsman, which was originally established through Presidential Decree (Keppres) Number 44 of 2000 concerning the National Ombudsman Commission, was enhanced with the enactment of Law (UU) Number 37 of 2008 concerning the Ombudsman of the Republic of Indonesia. The Indonesian Ombudsman has strategic functions, duties and authority, especially in supervising the implementation of public services. In Law Number 37 of 2008, it is determined that the Indonesian Ombudsman functions to supervise the implementation of public services organized by state and government adm?nistrators, both at the center and in the regions, including those organized by State-Owned Enterprises (BUMN), Regional-Owned Enterprises (BUMD), and State-Owned Legal Entities (BHMN), as well as private entities or individuals who are tasked with providing certain public services. The Indonesian Ombudsman also has the task of receiving, examining and reading reports regarding alleged maladm?nistration in the implementation of public services; has the authority to ask for information and make summons, as well as make recommendations regarding the completion of the report (including recommendations for paying compensation and/or rehabilitation to the injured party). The Indonesian Ombudsman currently not only has the authority to approve public reports, but also has the authority to carry out investigations on his own initiative; They can even impose sanctions through recommendations that are final, binding, and must be implemented by the recipient of the recommendation.

In carrying out its duties to prevent maladm?nistration, the Ombudsman is given the authority to provide advice to the President, DPR/DPRD, regional heads or heads of state adm?nistrators to improve and perfect the organization in terms of service procedures and laws and regulations in order to prevent maladm?nistration. For reports that are proven to be mal-adm?nistrative, the Ombudsman does not provide legal sanctions like the Judicial Institution (magistrate of sanctions) which can impose penalties and fines. As a state institution that has the authority to monitor and take action against violations of public services, the Ombudsman can impose sanctions in the form of adm?nistrative sanctions on the reported party and his superiors who do not implement recommendations. Meanwhile, criminal sanctions are imposed on anyone who obstructs the Ombudsman in carrying out an examination imposed by a judicial institution where the examination of the party obstructing is submitted on the basis of a report from the ombudsman. The supervisory capacity to obtain horizontal accountability between fellow state institutions owned by the ombudsman is limited to the right to obtain answers. Although the ombudsman’s capacity as “a sanctioned giver” for state institutions that commit maladm?nistration in public services, is limited to adm?nistrative sanctions, the ombudsman can still carry out a good supervisory function over state adm?nistrators at large. Because in Law no. 28 of 1999 concerning state adm?nistrators who are clean and free from corruption, collusion and nepotism (KKN), the definition of state adm?nistrators refers to all state officials who carry out executive, legislative, judicial functions and other officials whose main functions and duties are related to state adm?nistration.

3.4. Judiciary Branch: Supreme Court (MA) and Constitutional Court (MK)

According to UUD 1945, Indonesia constitution, Judicial power in Indonesia is exercised by the Supreme Court and subordinate judicial bodies as well as the Constitutional Court. As the highest court in the rule of law systеm, the Supreme Court has authority to supervise and oversee all judicial processes over the high courts and district courts, as it mentioned in the law No. 3/2009 concerning the Supreme Court. It also stated in Article 24A paragraph (1) of the 1945 Constitution that the Supreme Court has the authority to adjudicate at the cassation level, examine statutory regulations under the law against the law and has other powers granted by law. Furthermore, according to the 1945 Constitution, the obligations and powers of the Supreme Court include giving consideration to the President concerning granting clemency and rehabilitation. Based on these authorities, it is impossible to list the Supreme Court to have accountability relation with president or other elected officials since it does not have capacity to demand answerability of the president or even the member of parliament. Despite that, the role of the Supreme Court is legitimate as monitoring state institutions to control public officials because of its role to uphold justice and rule of law in Indonesia, specifically when the public officials are committed to an unlawful act in general, corruption, bribery, and other criminal behavior.

Another existing judicial actor is the Constitutional Court (MK) which was constituted based on the mandate of Article 24C of the UUD 1945. Normatively, MK has the authority to make final decisions on law reviews against the Constitution, decide on disputes over the authority of state institutions whose powers are granted by the Constitution and on the dissolution of political parties and also to settle disputes about the results of general elections. In spite of that authorities, MK is the only court which has capacity to impose sanctions toward the president when the president and/or vice president are suspected of violating the law and no longer meet the requirements as president and vice president. Therefore, the accountability relationship between MK and president is strong enough to control the president to remain responsible and accountable. If the accusation of the president’s wrongdoings is proven, MK can decide to remove the President from office and establish the impeachment.

3.5. Attorney General’s Office

The Attorney General’s office is a non-ministerial government institution in which the top leadership of the office is held by the attorney general. The position of the attorney general as a state institution is similar to ministries in the presidential cabinet. In other words, it is placed at ministerial level so the attorney general’s office is not responsible hierarchically under any ministry. In this regard, the attorney general leads the attorney general’s office which is divided to some extent into legal areas starting from the provincial level (high prosecutor’s office) to the district (state prosecutor’s office) throughout Indonesia. In other words, the Attorney General is a state official who acts as the leader and the highest person in charge of the attorney general’s office and as the controller of the duties and authority of the high prosecutor’s and state prosecutor’s office in Indonesia. In carrying out the duties of judicial power and as part of government institutions, the prosecutor’s office is directly responsible to the president because the Attorney General is appointed and dismissed by and is responsible to the president as stated in Article 19 of Law no. 5/1991 concerning the Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Indonesia. Considering its role, the attorney general is significantly contributing to monitor and control the legal transgressions from the President or any other public officials. Not only that, the attorney general has the capacity to impose sanctions in the law enforcement systеm whenever the president or other state officials violate the existing law. Therefore, these roles directly refer to the horizontal accountability relationship between attorney general’s office and state actors, including the incumbent president.

4. The Performance of Horizontal Accountability

The mapping of key institutions in horizontal accountability that comprise the judiciary branch and oversight agencies in Indonesia has been written in the constitution and also in the specific regulation. However, the fact of deficiencies of horizontal accountability portrayed in the data of horizontal accountability index in the figure 1 indicates that the performance of each key institution has a challenge to address.

4.1. The Performance of Constitutional Court

The key institution within the judicial branch to minimize executive aggrandizement is the Constitutional Court, as the Supreme Court and Judicial Attorney’s Office primarily focus on law enforcement within the general justice systеm. Since MK was formed in 2003, the performance of MK has gained public trust toward governance. However, in the late Jokowi’s presidency, the public trust toward the Constitutional Court decreased tremendously. The nomination of the president and vice-president candidate to run in the election 2024 has been the political reality to destroy Constitutional Court dignity. In other side, this proves executive aggrandizement, as scholars suspected there was a political scenario to push Gibran Rakabuming Raka, the son of President Joko Widodo, to run for the presidential and vice-presidential election, even though Gibran failed to meet the age requirement to run as a vice-presidential candidate.

4.2. The Performance of Oversight Agencies (Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) and Ombudsman)

The key institution to establish horizontal accountability toward the president as the head of government is the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) because the Ombudsman only deals to control the public officials in providing direct public services to society. However, the attempts to weaken the KPK successfully inhibited this oversight agency from maximizing its roles in monitoring President involvement in corruption. The deterioration of these oversight agencies began with the revocation of KPK’s authority and placed the institution under the presidential power. In this scenario, KPK has become the government’s agent of accountability that is responsible to the president, not the oversight agencies to monitor any President wrongdoing. This power arrangement of KPK has worsened by the very head of KPK, Firli Bahuri, who has committed bribery and corruption. Consequently, this political reality depicted how KPK is not performing in a positive direction to enhance horizontal accountability.

5. The Gaps between” De Jure and De Facto” of Sustaining Horizontal Accountability

Despite being strongly regulated in the constitution and various acts, the principle of check and balances is hard to implement. The challenge of each institution to perform the checks and balances toward one another is influenced by domestic politics. Indonesia adopts the presidential systеm combined with a multi-party systеm. This combination tends to create political deadlock if the president fails to accommodate diverse political parties’ interests. Therefore, the elected president tried to create a strong coalition with the political parties to create effective and solid government and reduce the possible opposition to occur. Thus, the favorable political accommodation chosen by the president determined the coalitional relation with the political parties, including with the state legislature who was also the member of existing political parties. In practice, the state legislature’s performance depended on the policy of political parties and their elites. Then the checks and balances model in the Indonesian government is more determined by the relation between the President and the state legislatures, and their affiliate political parties since there were no significant opposition parties to balance and control the president and his supporting coalition.

The president’s focus on maintaining relations with both the coalition and the opposition in parliament leads to the marginalization of the roles of other state institutions. According to Lili Romli (2021), this notion ultimately leads other state institutions such as the DPD as a second chamber and judicial institutions such as the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court to be incapable of performing their control roles both in legislative functions and in law enforcement. This practice eventually undermines the role of the judiciary, which tends to be a tool to support executive power or support DPR policies in performing their functions. The absence of the coalition as the final hope to institutionalize the checks and balances function has also contributed to the degradation for the quality of democratic governance in Indonesia. This condition is exacerbated by the design of a representative institution that places a second chamber with limited functions, solely in matters of legislation. As a result, under this condition it is obvious that the implementation of horizontal accountability is almost non-existent. In addition, there is an imbalance of function and authority between the first and second chambers in the parliament, leading to the absence of internal checks and balances in the parliament. This highlights the paradox of horizontal accountability resulting from unequal power among state actors. Moreover, the continued dominance of the DPR in coalition with the government tends to eventually produce transactional and compromising legal products. Thus, the checks and balances in Indonesia are determined by the President as head of the executive branch and the political parties and their MPs in the legislative branch. Therefore, this section will focus on the relationships between DPR and the president and between the Judiciary and the president at the national level to convey how horizontal accountability works in Indonesian governance.

5.1. The Relation of DPR and President: Coalition Hinders the Horizontal Accountability

The political phenomena that occurred in Indonesia, especially considering the implementation of the direct presidential election, sent a message that coalitions are always built by the incumbent President, both at the beginning of the election and during the adm?nistration of a government, to maintain power and political stability. However, the formation of a coalition including almost all political parties in the parliament became known as the fat (gemuk) coalition.

The trend of forming a ‘gemuk’ coalition manifested after elections in the Reformation era. It was obviously seen after the 2004 elections, as at first, the Presidential Adm?nistration of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY)-Jusuf Kalla (JK), which was in office from 2004-2009, had a minority coalition in parliament where the vote obtained was only 7.45%, which meant that there were only 56 seats or 10.26% in the DPR (Fitra Arsil 2017: 215). This minority condition in parliament certainly made the SBY-JK Adm?nistration feel insecure; therefore, a gemuk was formed in the DPR where almost all parties joined together to form a coalition, except the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-Perjuangan), which played the role of opposition. The 2009 presidential election resulted in the SBY-Boediono Adm?nistration, which held office from 2009-2014 and again led to a fat coalition forming in the DPR. The coalition that succeeded in securing SBY’s government for two terms resulted in the next presidential leadership preserving the culture of fat coalitions as a step towards the success of governance. Jokowi, in his first and second terms following the election of 2014 and 2019, also built a coalition following the fat frame in the government, namely during the Jokowi-JK Adm?nistration from 2014-2019. Even for the second 2019-2024 term, the Jokowi-Ma’ruf Advanced Indonesian Cabinet brought in figures who were leaders of the opposition party as ministers.

The explanation of how the President formed the above coalition indicates that there currently exists no opposition strong enough to hold the President responsible for horizontal accountability. The formation of these coalitions is based on cartel politics and has led to the accountability trap. This condition reflects what Slater has mentioned about the accountability trap that hinders democratization in governing the state at the national level. Meanwhile, until almost two decades post-reform, non-party and extra-parliamentary circles performed the role of the opposition, which was sporadic and unusable as a barometer of control over an effective government. As a result, instead of becoming a sphere for a healthy democratic life, Indonesia is currently trapped in an oligarchic practice due to its positioning of the interests of a few above those of the masses. The interests of a group of people close to power often manipulate government policies intended for the people. The interests of a group of people close to power often manipulate government politics meant for the people. Democracy tends to be artificial, thus allowing the government to reap the results without effective opposition. The failure of the institutionalization of the opposition indicates that the president is not being subject to checks and balances by the parliament. The opposition only exists before the election in the context of electoral contestation marked by the union of all ranks of the leaders of the opposition parties to the elected president. The existing opposition is not based on program conflicts, differences in political views, or ideologies, hence indicating no practice of checks and balances to balance the president’s executive power.

5.2. The Relation Between President and MK as The Judiciary: Impeachment Barely Possible

Indonesia’s judicial institution, the Constitutional Court (MK), has the authority to handle the impeachment process to hold the executives accountable, especially in the case that the president and/or vice-president is suspected of having violated the law or no longer fulfils the requirements for president and/or vice-president. The procedure for impeaching the president and/or vice-president is essentially a series of long processes and requires the involvement of several high state institutions other than the Constitutional Court itself, including the People’s Representative Council (DPR) and the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR). In this case, the initiation of the impeachment process can be submitted only by the DPR, which must submit it to the MPR. However, the DPR can only submit a request to the Constitutional Court with the support of at least 2/3 of the total number of DPR members present at a plenary meeting attended by at least 2/3 of the total number of DPR members. This requirement is difficult to fulfil because the majority of DPR members come from the election-winning party and its coalition partners. Consequently, the DPR cannot arbitrarily submit a request for the impeachment of the president and/or vice-president without the support of at least 2/3 of its members. After the submission, if the Constitutional Court decides that the president and/or vice-president has violated the law, the DPR holds a plenary meeting to submit the proposal to dismiss the president and/or vice president to the MPR. The MPR Plenary Session should be attended by at least 3/4 of the members and approved by at least 2/3 of the members present, after which the president and/or vice-president has the opportunity to present their explanations at the MPR plenary session. Thus, the MPR’s decision ultimately determines whether or not impeachment can proceed.

In practice, the impeachment issue has occurred once against President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) that arose related to the investigation into the Century Bank case. The results of the temporary conclusions of the DPR special committee regarding Century Bank show that the government received support from two factions, namely the Democratic Party and the National Awakening Party (PKB). Seven other political parties, PKS, Golkar Party, PDIP, Gerindra, Hanura, PPP and PAN, conversely stated that granting Bank Century bailout funds violated the law. In the beginning, false accusations were aimed only at monetary authorities and assistants to the President. Still, as development progressed, political parties began to emerge, although not in a “vulgar” direction towards the president, as they too were considered partly responsible for how the government was running, especially regarding the bailout process for Century Bank. However, based on the regulation on the impeachment process, it seems that the conditions for impeaching the president are not easy to fulfil; based on the results of the presidential election, the Democratic Party, which supports SBY and Boediono, has received genuine support from more than 60% of its constituents. Therefore, the requirement of support by 2/3 of the number of DPR members is also not easy to achieve because the majority of DPR members come from the Democratic Party with the support of their coalition partner political parties. Of course, the Democratic Party and its coalition will try their best to thwart the impeachment efforts of their political opponents. Measures taken towards impeachment are currently difficult to attain because DPR is mostly part of the fat coalition and is allied with the president.

Finally, the attempt to do presidential impeachment is not easy to accomplish because the mechanism required to enact it is quite long, with conditions that are also not easy to satisfy. The challenge to oversee the president to be accountable leads to the paradox of horizontal accountability, because accountability is almost non-existent since the Constitutional Court should review the president’s case based on a parliamentary decision.

6. Conclusion

Before the constitutional amendment, the power-sharing arrangement of the Indonesian government was still unclear because it contained elements of both a parliamentary and a presidential systеm. In this systеm, the President was elected and appointed by the MPR as the highest state power holder. Therefore, the President’s role is mandated by the MPR, making the President responsible to the MPR. In other words, a parliamentary feature is visible through the MPR roles, but on the other hand there are also characteristics of a presidential systеm in which the President has double roles as the head of state and the head of government. The changes to the 1945 Constitution therefore clarified the Indonesian government systеm with the adoption of the Direct Presidential election systеm to eliminate the superior role of MPR.

Beside the vague condition of the government systеm, President Soeharto benefited by the centralized power-sharing arrangement in the executive branch. It is written in the constitution wherein based on 37 articles stated in the 1945 constitution, 13 articles of them regulate the authorities of the president (Article 4 to Article 15 and Article 22). In addition, the President also exercises statutory powers, and holds powers related to law enforcement such as the right to give abolition and amnesty. Moreover, almost all legal products were legalized and enacted with the direction of the President or aimed to strengthen the President’s power. This condition happened due to the absence of checks and balances that could be carried out by the legislative and judicial branches to balance the role of the president as the executive. Even though in the Constitution before the amendment, there was a parliamentary character where the President had to consider the MPR and needed the approval of the DPR to form a law, in reality, during the New Order era, no laws were enacted from the initiative of the DPR since all initiatives originated from the executive. In other words, the DPR only had to pass them whether they liked it or not. So that satire often appears against the DPR whose role is to be “stampers as yes man institution.”

The experience of amending the 1945 Constitution in the 1999-2002 generated a fundamental change in Indonesia. The change of the constitution was purposely aiming to implement checks and balances between state branches. However, the checks and balances arrangement in Indonesia differs from the general conception of checks and balances mechanism that mainly root into the separation of power between each state branch. In Indonesia, the executive, legislative, and judicial branch works with coordination in performing their authorities, for instance, in the national policy making process, parliament would always work together with the president. Indonesian scholars referred to the systеm of checks and balances in Indonesia as the adoption of a diffusion of power arrangement in the government. Moreover, another reason for constitutional change in Indonesia is to strengthen the presidential systеm, as Indonesia has a mixed government systеm that combines parliamentary and presidentialism. Constitutional amendment thus has implications for changes in the overall government systеm to induce government accountability. There are at least three points of institutional change regarding the constitutional arrangements.

First, changes to strengthen the presidential government systеm clarified the division of power between executive, judicial and legislative authority. However, to avoid power centralized more into the President as the head of state and head of government, the new power arrangement was made to reduce the president’s authority only in the range of executive division. This new model of power sharing arrangement has been improved compared to the one existing in the previous regime wherein the president once had the extra-power overrun into legislation and to interfere with law enforcement. Second, modifying the MPR’s position from the highest state institutions to become a state institution with very limited authority equal with other existing institutions at the national level. This repositioning of the MPR resulted in equality between state institution from all branches so that horizontally they have capacity to control and balance one another. Thus, the function of checks and balances can be implemented. Third, changes to strengthen the role of the DPR in the field of legislation and to oversight executives. The three reasons mentioned as the background of constitutional amendment shows the seriousness of the newly formed post-reform government to implement horizontally checks and balances mechanisms in state institutions. Therefore, the new constitution after the fourth amendment emphasized the adoption of the presidential systеm and also emphasized the application of the checks and balances’ principle between the state branches including executive, judicial and legislative.

However, the performance of each branch of government showed there was a challenge to establish both horizontal accountability and checks and balances mechanisms. The condition occurs due to the weakened position of KPK and the weak opposition in Indonesia political systеm. These conditions generated the paradox of accountability resulting from the inequality of power and resources between actors. To resolve this paradox, ideally, both parties should form relatively autonomous agencies that do not stand in a relation of formal subordination or superiority to one another. In other words, horizontal accountability presupposes a prior division of powers and a particular internal functional differentiation of the state. In the case of Indonesian politics, the unequal power between the executive, legislative, and judiciary branches is the result of formal and informal institutions. The legislative has unequal authority to check the president’s accountability because it has been weakened by cartel politics seen as necessary to form a coalition with the government before and after the election. Meanwhile, the judiciary has a similar dilemma where the presidential impeachment requires the provision and convention of parliamentarians co-opted by the government coalition. This condition even further leads to an accountability trap.

Consequently, the absence of opposition as the last resort to institutionalize horizontal accountability from the legislative branch toward the president has also contributed to the degradation of the quality of democratic governance in Indonesia. The design of a representative institution that places a second chamber with limited functions solely in terms of legislation has exacerbated this condition. As a result, under this condition, it is obvious that the implementation of horizontal accountability is almost non-existent. In addition, there is an imbalance of function and authority between the first and second chambers of the Parliament, leading to the absence of internal checks and balances within the parliament. This condition evidences the paradox of horizontal accountability by resulting in unequal power between state actors. ■

References

Adserà, A, Boix, C. and Payne, M. 2003. “Are you being served? Political Accountability and Quality of Government.” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 19, 2: 445-490.

Ambardi, K. 2008. The making of the Indonesian multiparty systеm: A cartelized party systеm and its origin. The Ohio State University.

Arndt, Christiane and Oman, Charles. 2006. Uses and Abuses of Governance Indicators, Development Center Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Arsil, Fitra. 2017. Teori Sistem Pemerintahan: Pergeseran Konsep dan Saling Kontribusi Antar Sistem Pemerintahan di Berbagai Negara (Government Systеms Theory: Conceptual Shifts and Mutual Contributions Between Government Systеms in Various Countries).

Buehler, M. 2010. “Decentralisation and Local Democracy in Indonesia: The Marginalisation of the Public Sphere in Aspinall.” in E., & Mietzner, M. (Eds.) 2010. Problems of Democratisation in Indonesia: Elections, Institutions and Society. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Choi, E., & Woo, J. 2010. “Political corruption, economic performance, and electoral outcomes: A cross-national analysis.” Contemporary Politics 16, 3: 249-262.

Coppedge M, Gerring J, Lindberg SI, Skaaning S, Teorell J, Altman D, Andersson F, Bernhard M, Fish SM, Glynn A, Hicken A, Knutsen CH, Marquardt KL, McMann K, Mechkova V, Miri F, Paxton P, Pernes J, Pemstein D, Staton J, Stepanova N, Tzelgov E, Wang Y, Zimmerman B. 2016. 2016 V-Dem Dataset Version 6.2. Varieties of Democracy V-Dem Project.

De Almeida Lopes Fernandes, Gustavo Andrey, Marco Antonio Carvalho Teixeira, Ivan Filipe de Almeida Lopes Fernandes, and Fabiano Angélico. 2020. “The Failures of Horizontal Accountability at the Subnational Level: A Perspective from the Global South.” Development in Practice 30, 5: 687-693.

Freedom House. 2022. “Freedom in the World 2022: The Global Expansion of Authoritarian Rule.” https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2022/global-expansion-authoritarian-rule (Accessed January 29, 2024)

Hagopian, F. 2016. “Brazil’s Accountability Paradox.” Journal of Democracy 27, 3: 119–128.

Hamid, Sandra. 2012. “Indonesian Politics in 2012: Coalitions, Accountability and the Future of Democracy.” Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 48, 3: 325-345.

Hidalgo, D. F., J. Canello, and R. Lima de Oliveira. 2016. “Can Politicians Police Themselves? Natural Experimental Evidence from Brazil’s Audit Courts.” Comparative Political Studies 49, 13: 1739–1773.

Jones, G.W. 1992. “The Search for Local Accountability.” in S. Leach (editor). Strengthening Local Government in the 1990s. London: Longman, 49-78.

Katz, Richard S., and Peter Mair. 1995. “Changing Models of Party Organization and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party.” Party Politics 1, 1: 5-28.

Kenney, Charles D. 2003. “Horizontal Accountability: Concepts and Conflicts.” Democratic Accountability in Latin America 165: 55.

Khotami, Mr. 2017. “The Concept of Accountability in Good Governance.” In International Conference on Democracy, Accountability and Governance (ICODAG 2017), 30-33. Atlantis Press.

Kristiansen, Stein, Agus Dwiyanto, Agus Pramusinto, and Erwan Agus Putranto. 2009. “Public Sector Reforms and Financial Transparency: Experiences from Indonesian Districts.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 31, 1: 64-87.

Lindberg, S. I. 2009. “Accountability: The Core Concept and Its Subtypes.” Africa Power and Politics. Working Paper No.1.

Lührmann, Anna, Kyle L. Marquardt, and Valeriya Mechkova. 2020. “Constraining Governments: New Indices of Vertical, Horizontal, and Diagonal Accountability.” American Political Science Review 114, 3: 811-820.

Mainwaring, S. and Welna C. 2003. Democratic Accountability in Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Melo, M. A., C. Pereira, and C. M. Figueiredo. 2009. “Political and Institutional Checks on Corruption: Explaining the Performance of Brazilian Audit Institutions.” Comparative Political Studies 42, 9: 1217–1244.

Mulgan, R. 2000. “Accountability: An Ever-Expanding Concept?” Public Adm?nistration 78, 3: 555-573.

O’Donnell, G. 1998. “Horizontal Accountability in New Democracies.” Journal of Democracy 9, 3: 112-126.

______. 2003. “Horizontal accountability: The legal.” Democratic Accountability in Latin America, 34.

Praca, S., and M. M. Taylor. 2014. “Inching Toward Accountability: The Evolution of Brazil’s Anticorruption Institutions, 1985–2010.” Latin American Politics and Society 56, 2: 27–48.

Rodan, Garry, and Caroline Hughes. 2014. The Politics of Accountability in Southeast Asia: The Dominance of Moral Ideologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Romli, Lili. 2021. “Bicameralism: Strengthening Political Representation at National Level.” Election Team Report – Center for Political Studies. Unpublished, Jakarta.

Roylance, Tyler. 2015. “Freedom Isn’t Always Forever.” Freedom House. January 29. https://freedomhouse.org/article/freedom-isnt-always-forever (Accessed January 29, 2024)

Said, Muhtar, Ahsanul Minan, and Muhammad Nurul Huda. 2021. “The Problems of Horizontal and Vertical Political Accountability of Elected Officials in Indonesia.” Journal of Indonesian Legal Studies 6: 83.

Sakib, N. H. 2020. “Horizontal Accountability to Prevent Corruption.” Global Encyclopedia of Public Adm?nistration, Public Policy, and Governance, 1–6. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3930-1

Sato, Yuko, Martin Lundstedt, Kelly Morrison, Vanessa A. Boese, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2022. “Institutional Order in Episodes of Autocratization.” V-Dem Working Paper 133. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4239798 (Accessed January 29, 2024)

Schedler, Andreas. 1999. “Conceptualizing Accountability.” in Marc F. Plattner, Larry Diamond, and Andreas Schedler, The Self- Restraining State: Power and Accountability in New Democracies. Boulder: Rienner Publishers, 13-29.

Schmitter, Philippe and Terry Karl. 1991. “What Democracy Is and Is Not.” Journal of Democracy Summer 1991: 103-109.

Schmitter, Philippe C. 1999. “The Limits of Horizontal Accountability.” in Marc F. Plattner, Larry Diamond, and Andreas Schedler, The Self-Restraining State: Power and Accountability in New Democracies. Boulder: Rienner Publishers, 59-62.

Shugart and Haggard. 2001. “Institutions and Public Policy in Presidential Systеms.” In Haggard and McCubbins, eds. Presidents and Parliaments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Slater, Dan. 2004. “Indonesia’s accountability trap: Party cartels and presidential power after democratic transition.” Indonesia 78: 61-92.

V-Dem Institute. 2023. “Democracy Report 2023: Defiance in the Face of Autocratization.” https://v-dem.net/documents/29/V-dem_democracyreport2023_lowres.pdf (Accessed January 29, 2024)

Williams, A. 2015. “A Global Index of Information Transparency and Accountability.” Journal of Comparative Economics 43: 804-824.

Ziegenhain, Patrick. 2015. Institutional Engineering and Political Accountability in Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Zúñiga, Nieves, Matthew Jenkins, and David Jackson. 2018. Does more transparency improve accountability? Transparency International.

[1] Researcher at the Research Center for Politics, National Research and Innovation Agency

[2] Director of Regional Research and Innovation Policy, National Research and Innovation Agency

[3] Article 5 Paragraph 1: The President shall be entitled to submit bills to the DPR. and Article 20: (1) The DPR shall hold the authority to establish laws. (2) Each bill shall be discussed by the DPR and the President to reach joint approval. (3) If a bill fails to reach joint approval, that bill shall not be reintroduced within the same DPR term of sessions. (4) The President signs a jointly approved bill to become a law. (5) If the President fails to sign a jointly approved bill within 30 days following such approval, that bill shall legally become a law and must be promulgated.

[4] Article 37: (1) A proposal to amend the Articles of this Constitution may be included in the agenda of an MPR session if it is submitted by at least 1/3 of the total MPR membership. (2) Any proposal to amend the Articles of this Constitution shall be introduced in writing and must clearly state the articles to be amended and the reasons for the amendment. (3) To amend the Articles of this Constitution, the session of the MPR requires at least 2/3 of the total membership of the MPR to be present. (4) Any decision to amend the Articles of this Constitution shall be made with the agreement of at least fifty percent plus one member of the total membership of the MPR. (5) Provisions relating to the form of the unitary state of the Republic of Indonesia may not be amended.

[5] Article 12: The President may declare a state of emergency. The conditions for such a declaration and the subsequent measures regarding a state of emergency shall be regulated by law. And Article 22: (1) Should exigencies compel, the President shall have the right to establish government regulations in lieu of laws. (2) Such government regulations must obtain the approval of the DPR during its next session. (3) Should there be no such approval, these government regulations shall be revoked.

[6] Article 20 paragraph 2: Each bill shall be discussed by the DPR and the President to reach joint approval and paragraph 5: if the President fails to sign a jointly approved bill within 30 days following such approval, that bill shall legally become a law and must be promulgated.

[7] Article 7B: (1) Any proposal for the dismissal of the President and/or the Vice-President may be submitted by the DPR to the MPR only by first submitting a request to the Constitutional Court to investigate, bring to trial, and issue a decision on the opinion of the DPR either that the President and/or Vice-President has violated the law through an act of treason, corruption, bribery, or other act of a grave criminal nature, or through moral turpitude, and/or that the President and/or Vice-President no longer meets the qualifications to serve as President and/or Vice-President. (2) The opinion of the DPR that the President and/or Vice-President has violated the law or no longer meets the qualifications to serve as President and/or Vice-President is undertaken in the course of implementation of the supervision function of the DPR. (3) The submission of the request of the DPR to the Constitutional Court shall only be made with the support of at least 2/3 of the total members of the DPR who are present in a plenary session that is attended by at least 2/3 of the total membership of the DPR. (4) The Constitutional Court has the obligation to investigate, bring to trial, and reach the most just decision on the opinion of the DPR at the latest ninety days after the request of the DPR was received by the Constitutional Court. (5) If the Constitutional Court decides that the President and/or Vice-President is proved to have violated the law through an act of treason, corruption, bribery, or other act of a grave criminal nature, or through moral turpitude; and/or the President and/or Vice-President is proved no longer to meet the qualifications to serve as President and/or Vice-President, the DPR shall hold a plenary session to submit the proposal to impeach the President and/or Vice-President to the MPR. (6) The MPR shall hold a session to decide on the proposal of the DPR at the latest thirty days after its receipt of the proposal. (7) The decision of the MPR over the proposal to impeach the President and/or Vice-President shall be taken during a plenary session of the MPR which is attended by at least 3/4 of the total membership and shall require the approval of at least 2/3 of the total of members who are present, after the President and/or Vice-President have been given the opportunity to present his/her explanation to the plenary session of the MPR.

[8] https://www.v-dem.net/data_analysis/CountryGraph/

Horizontal Accountability in Mongolia:

The Challenges of (Counter) Balancing

Ganbat Damba[1], Mina Sumaadii[2]

Academy of Political Education

1. Introduction

The 1992 Constitution is considered the “blueprint of Mongolia democracy” (Sanders 1992). This Constitution has served Mongolia’s democracy well, as to date, eight electoral cycles have been held regularly, yielding uncertain outcomes and fostering multiparty competition for the people’s votes. In the Varieties of Democracy Project’s liberal democracy index, Mongolia started with a score of 0.41 in 1991 and, with slight fluctuations, ended with a score of 0.49 in 2021 (V-Dem Project 2022). At its height, it reached 0.61 in 1999. This reflects that Mongolia’s road to democratic development was not smooth and had its ups and downs. Nonetheless, these scores consistently place Mongolia in the “electoral democracy” category. While this is an accomplishment in comparison to other post-communist states in the region, it is still a democracy which has institutional challenges and much room for improvement.

Based on this, this report examines the internal structure of Mongolian democracy from the point of institutional checks and balances that exist under the constitutional setting. Therefore, we present a concept of horizontal accountability, which is part of a series of constraints on government use of political power. In the Mongolian media and political discussions, horizontal accountability is not a commonly used term. As one of the cornerstones of good governance, it measures the extent to which the government is accountable to other branches (Lührmann et al 2017). This is a particularly important issue for Mongolian governance to address, given the scope of reforms that shifted the domestic power balances among the government branches in recent years. Moreover, due to the low level of trust in public institutions and a lack of belief in the impartiality of politicians (Sant Maral Foundation 2023), the public is increasingly turning to protests as a preferred measure to hold the government accountable. Overall, this suggests that citizens no longer have the patience to rely on institutional checks and balances to represent or defend public interests; instead, they are increasingly inclined to take matters into their own hands.

As a result, addressing the related governance issues is becoming an increasingly important task for the quality and durability of Mongolian democracy.

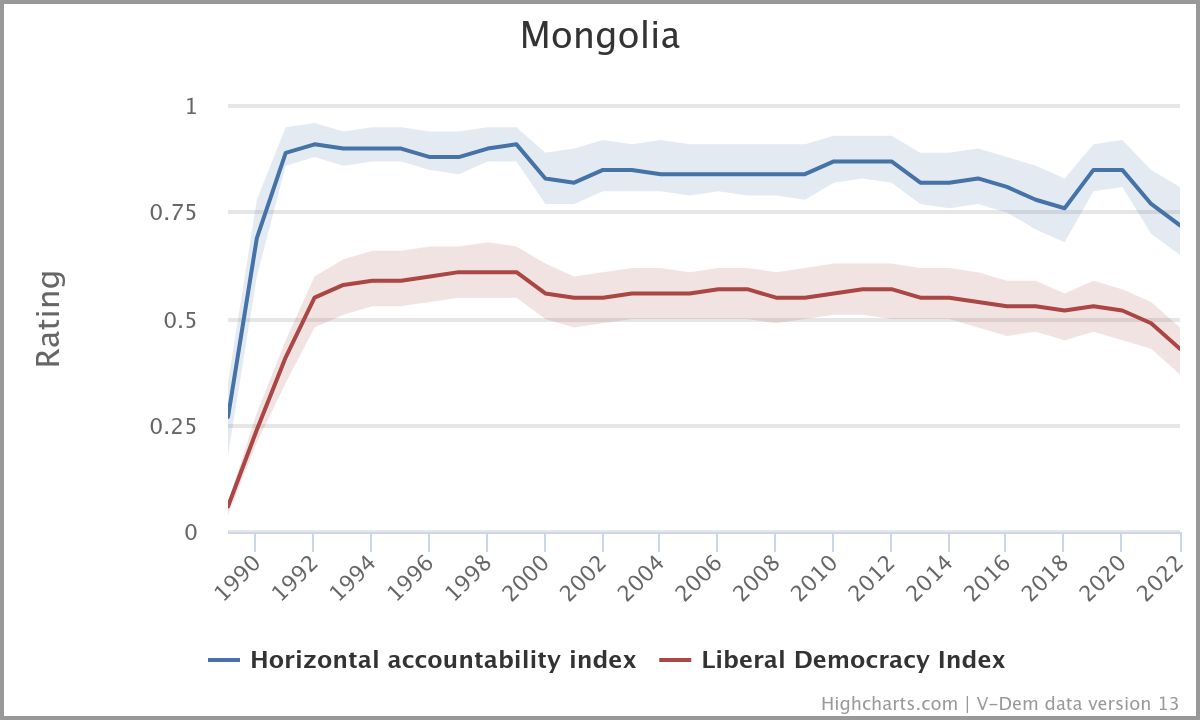

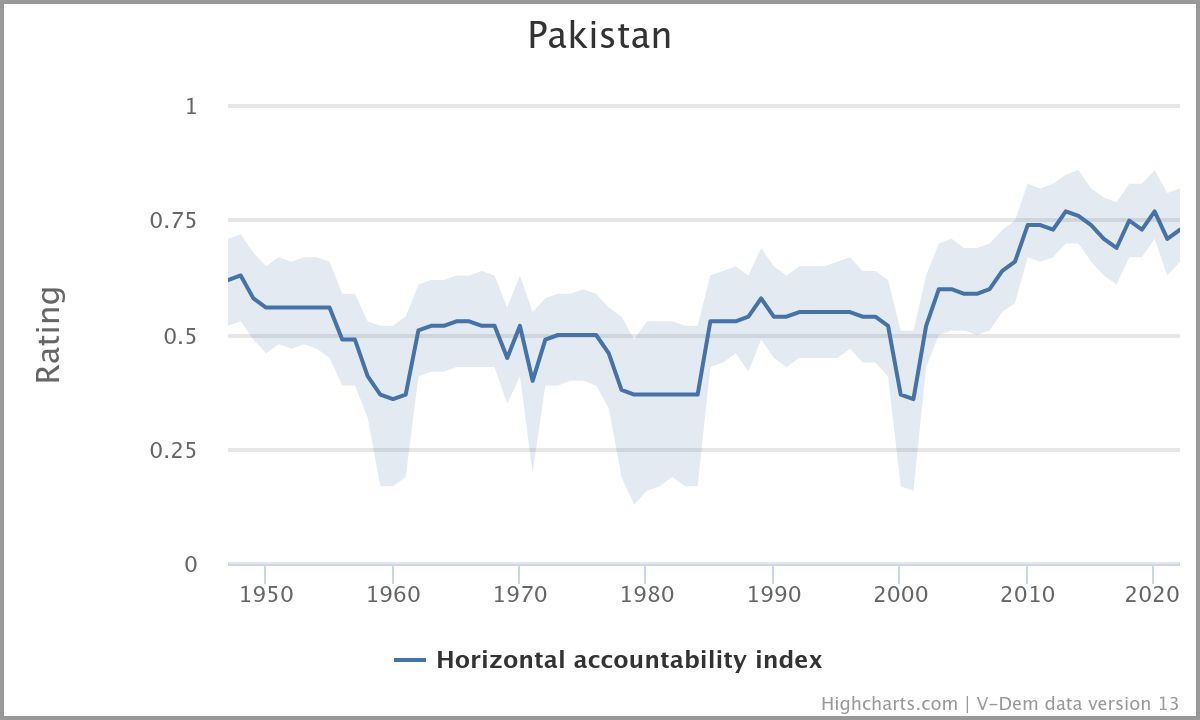

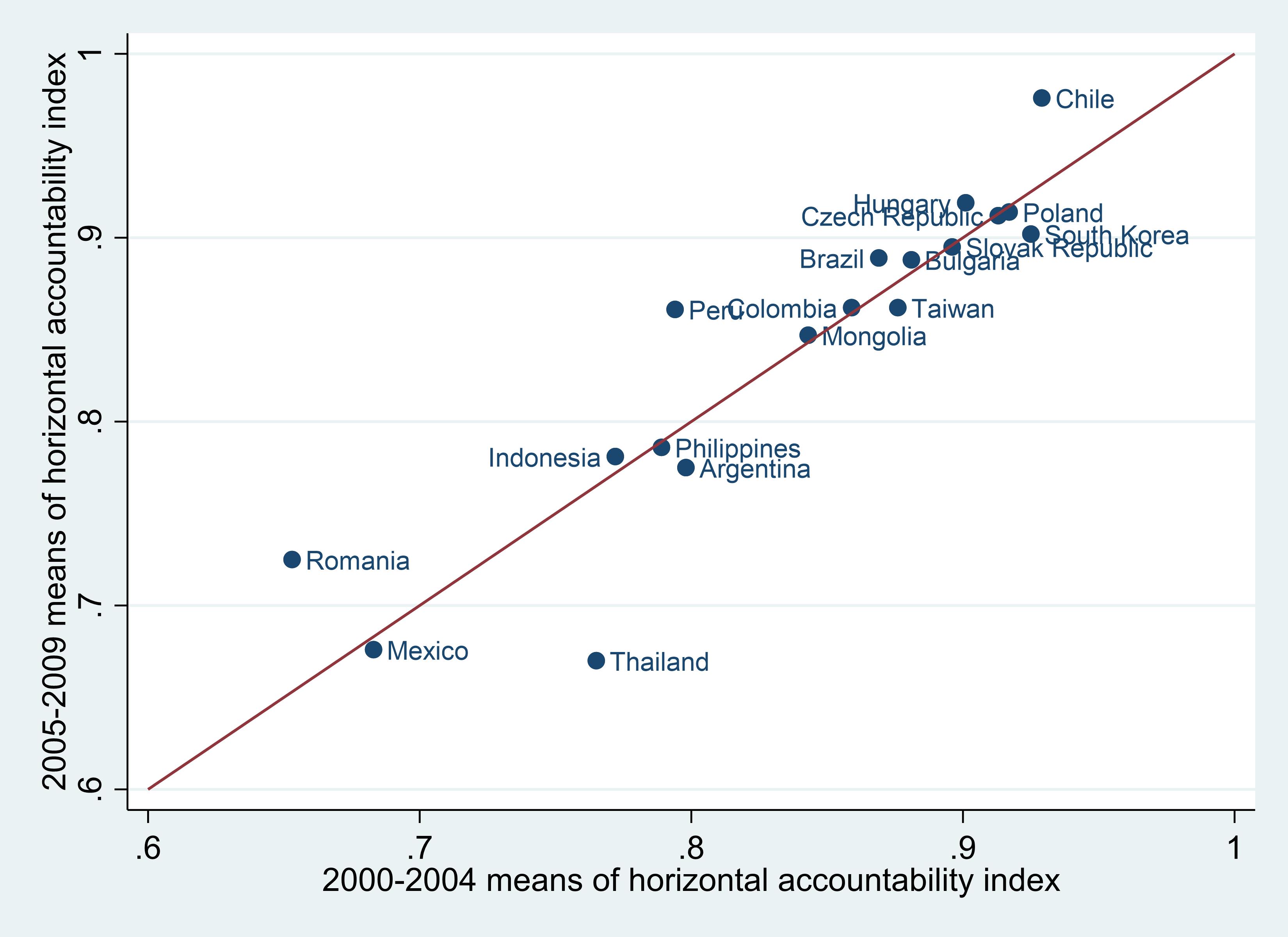

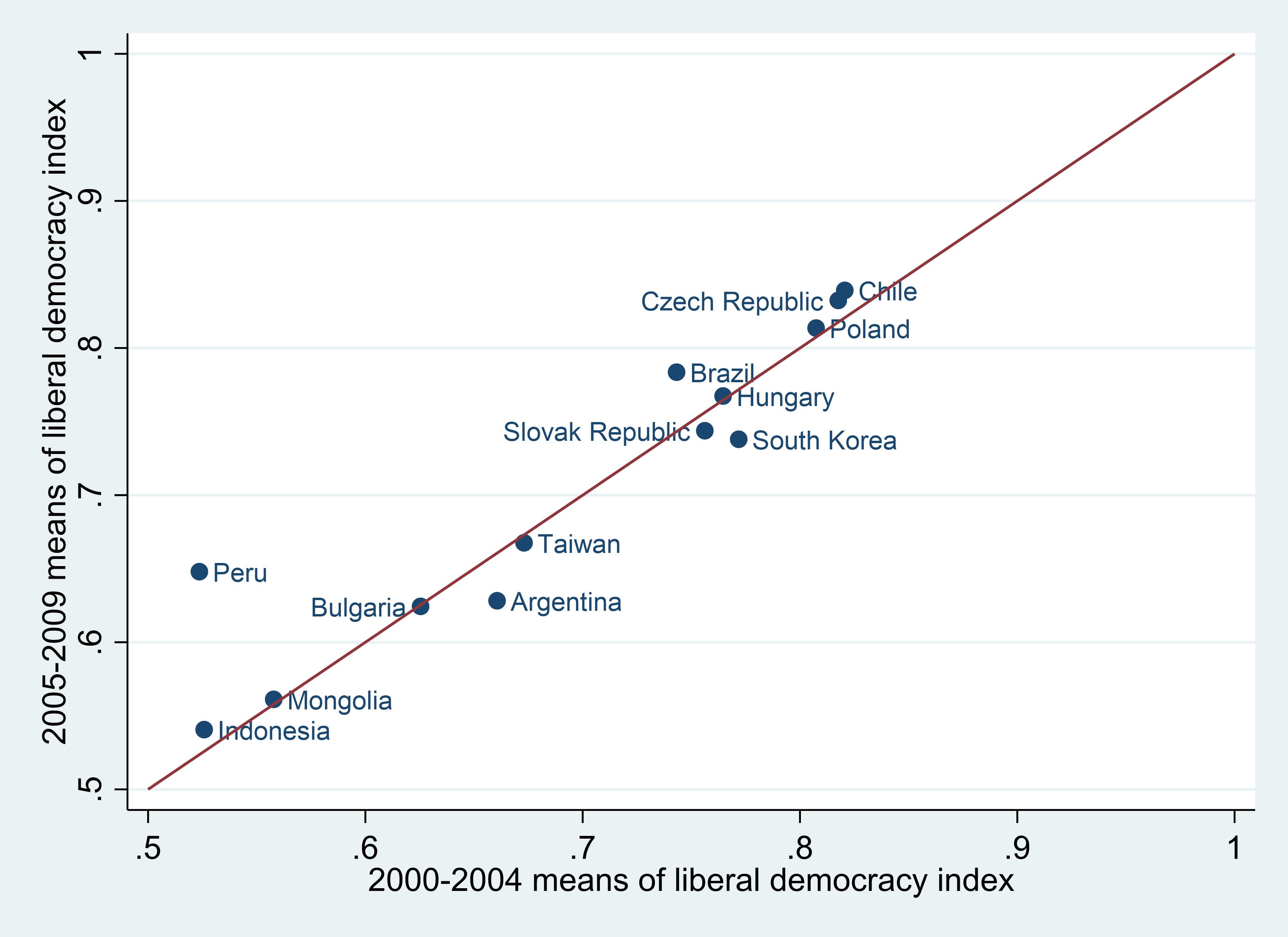

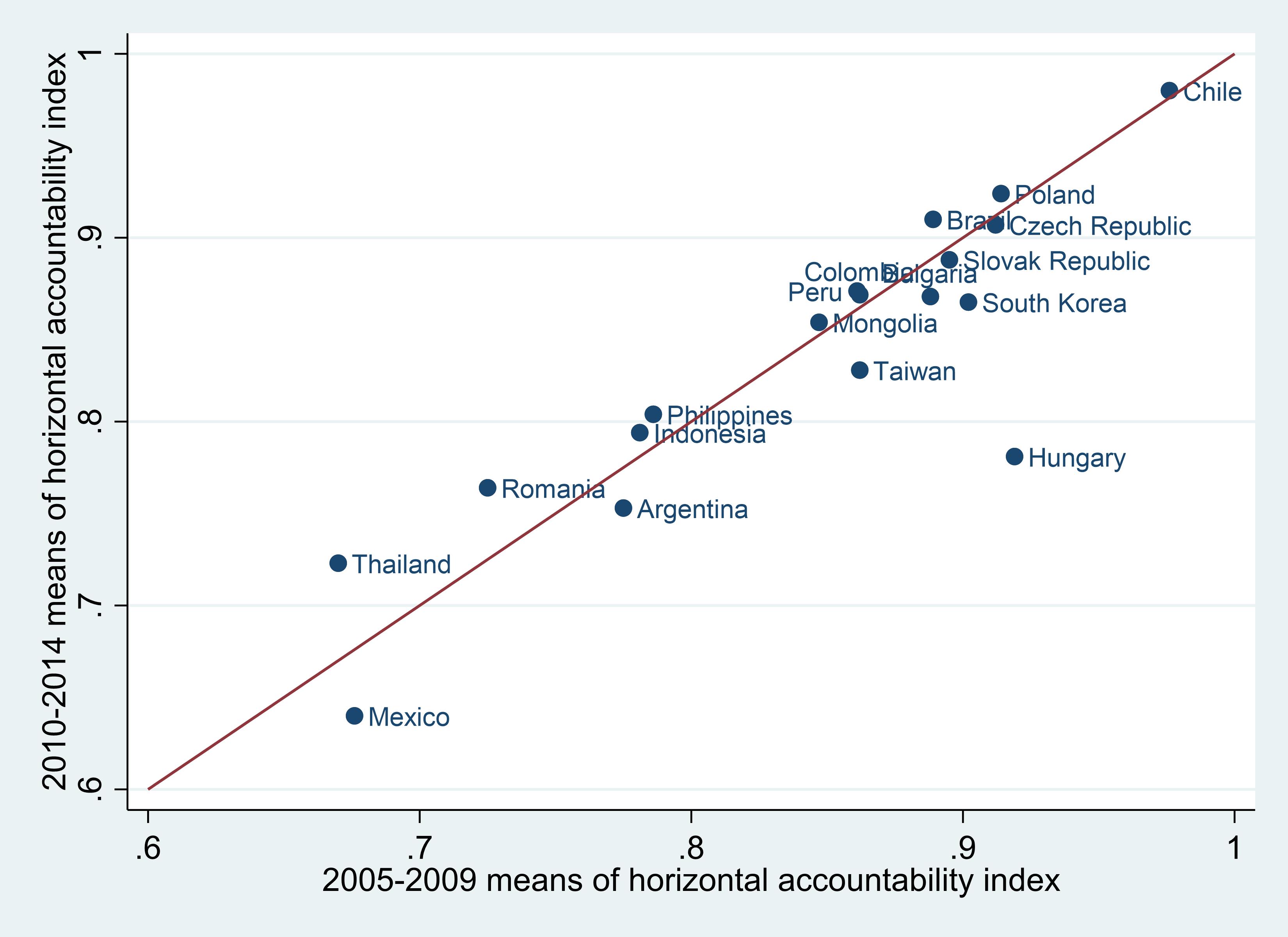

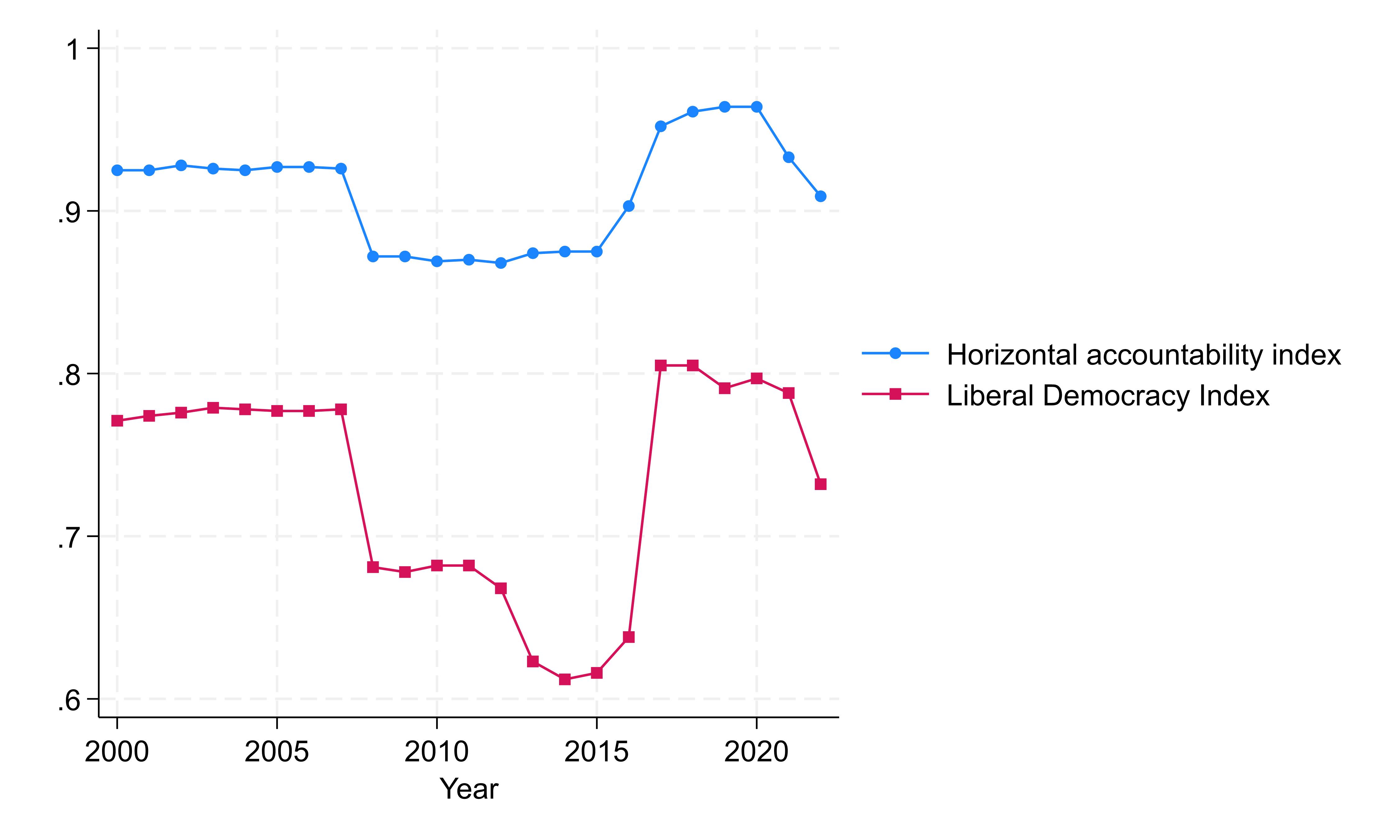

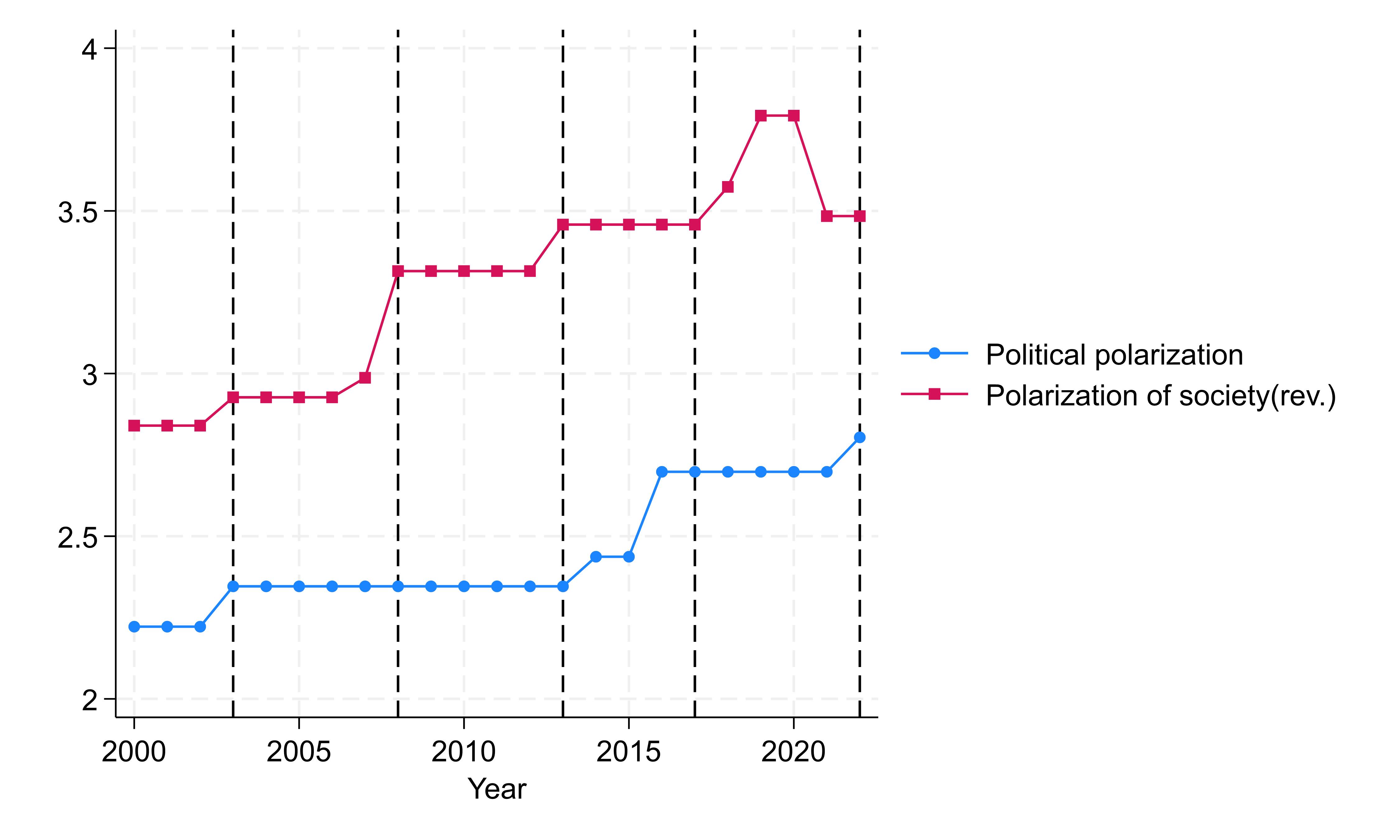

The V-Dem Project traces that the horizontal accountability index (scaled low to high (0-1)) in Mongolia had a score of 0.9 in 1991 and throughout the remainder of the 1990s (V-Dem Project 2022). Yet, it decreased following each constitutional amendment in 1999/2000 and 2019. Eventually, after fluctuations, it ended with a score of 0.78 in 2021 (V-Dem Project 2022). While in the broader historical context, the scores in the last three decades are at their highest level since Mongolia transitioned to democracy, the gradual decrease in the horizontal accountability index follows the general trend of declining government accountability.

Figure 1. Horizontal accountability and Liberal Democracy Indices in Mongolia

Source: V-Dem Project

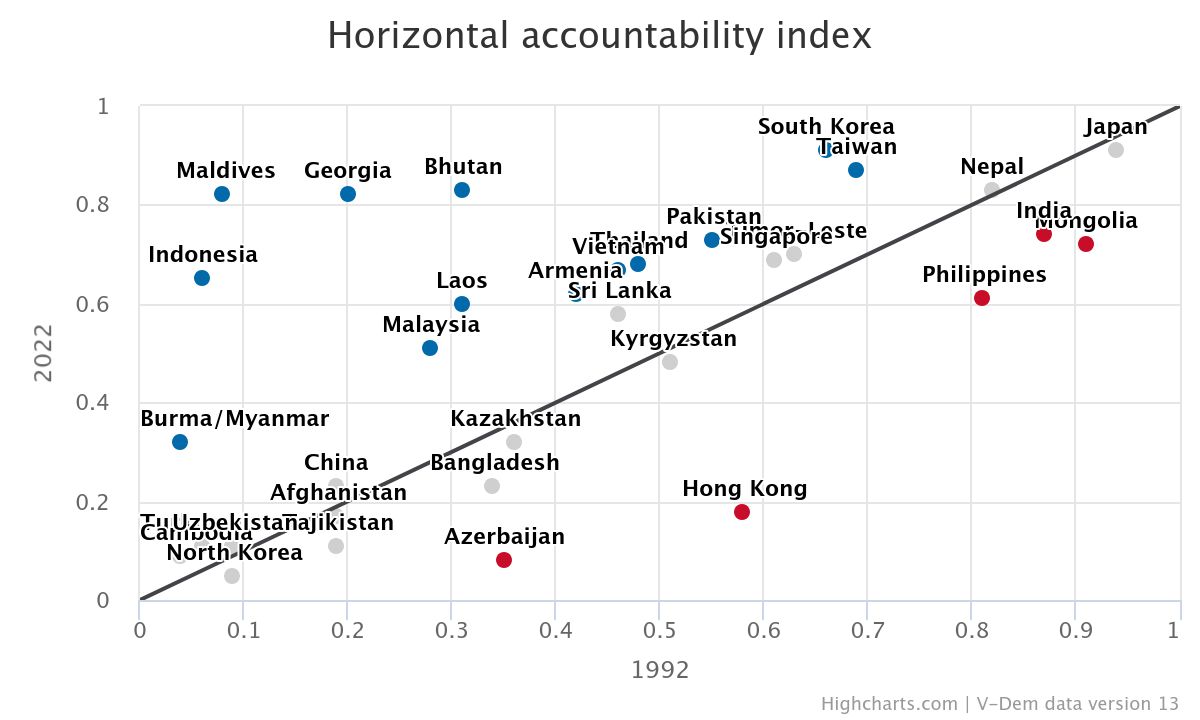

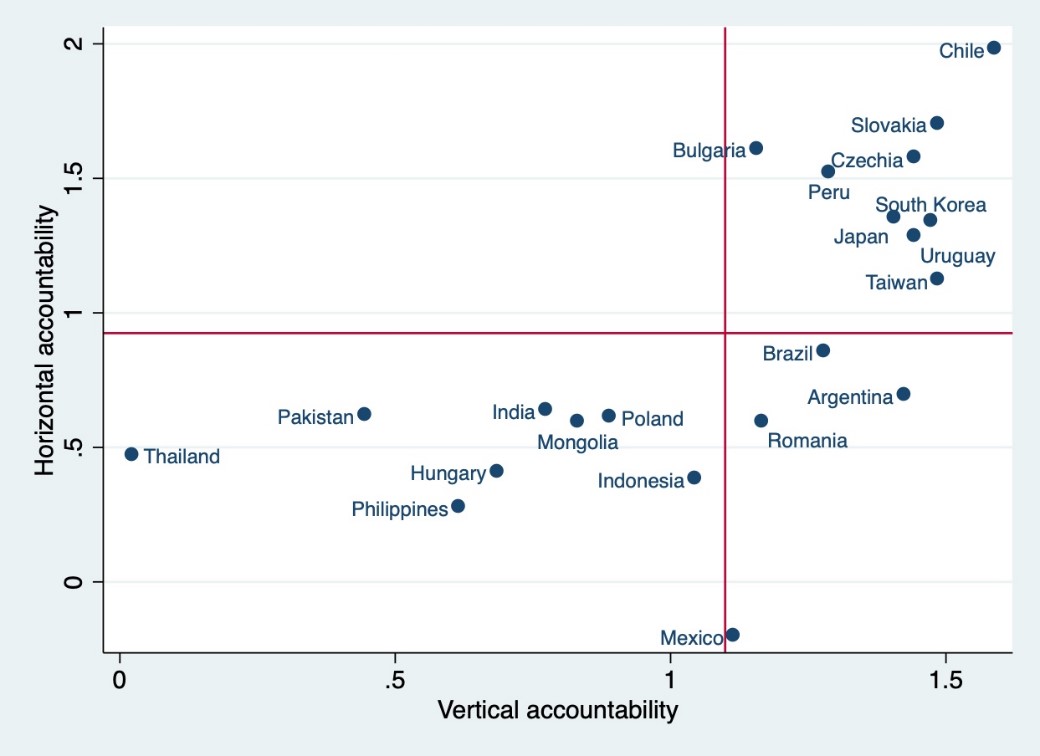

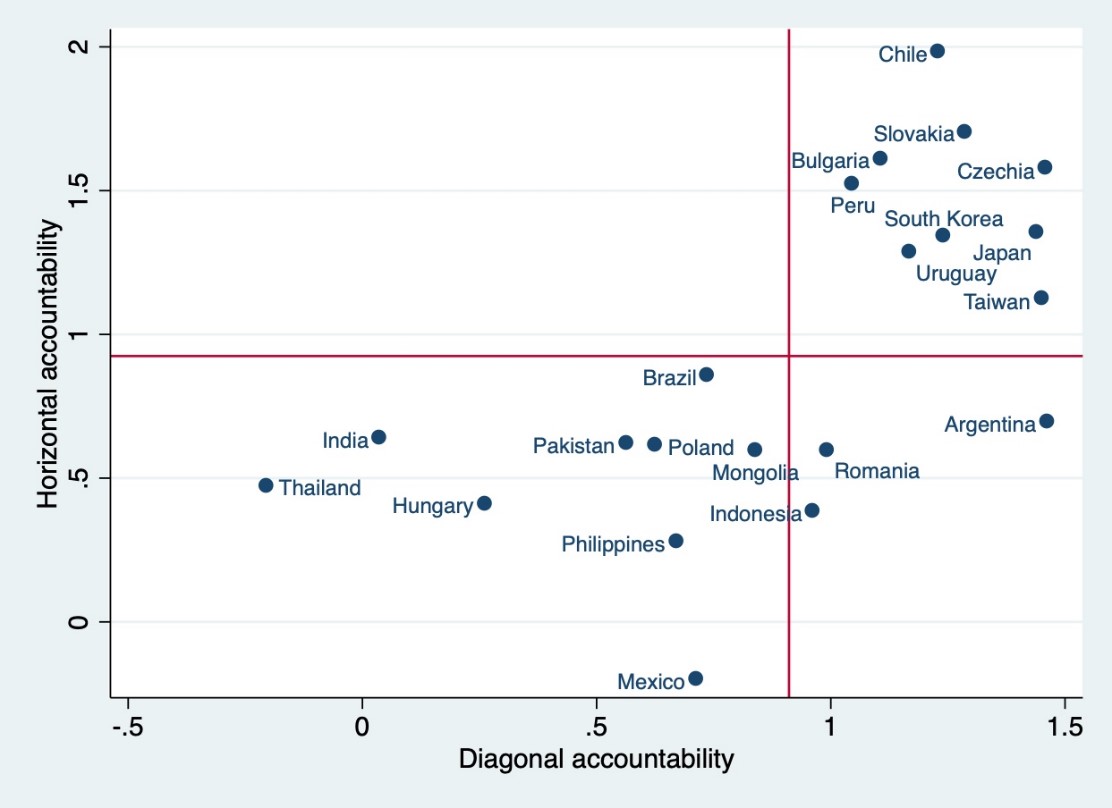

Regionally, Mongolian performance in horizontal accountability can be considered to be relatively high. While it is not at the level of advanced democracies, it performs better than countries within a similar income group. Based on the regional comparison of horizontal accountability, it can be seen that since the introduction of the 1992 Constitution, Mongolia’s position and decline are the most similar to India and the Philippines. Among these cases, the most important factor linked to the decline in horizontal accountability is the continuous weakening of judicial independence (See Reports on India and the Philippines). Similarly, Mongolia’s judicial branch struggles to maintain its independence following a series of constitutional and legal reforms. Moreover, in the existing political environment, oversight agencies have limited capacity and are not free from political interference. As a result, the constraints on the legislature and executive officials are weak.

Figure 2. Regional Comparison of Horizontal Accountability Index

Source: V-Dem Project

In cross-country research, Sato et al. (2022) found that in the process of autocratization, institutional decay starts with horizontal accountability, followed by declines in diagonal accountability, and ultimately vertical accountability. According to recent developments, some early signs of democratic erosion can already be found in Mongolia. As the balance of power between different branches becomes uneven, we will address some of the issues of concern, potentially pointing out some general prescriptions that can counter the process. Further investigation can also offer an institutional explanation of Mongolia’s good democratic performance and ineffective governance.

The main conclusion of the current cross-country research is that if a country has better horizontal accountability, then the quality of its democracy can be improved. At the same time, if there is erosion of horizontal accountability, the quality of democracy will deteriorate. Based on longitudinal observations by the V-Dem project, we can see that the decline in horizontal accountability is correlated with the decline in the quality of Mongolian liberal democracy.

Consequently, to uncover the factors contributing to this trend, the study is organized as follows. We begin with an assessment of Mongolia’s de jure and de facto horizontal accountability from a comparative perspective. It is followed by the introduction of a constitutional checks and balances systеm in Mongolia. Next, we describe the existing hierarchy of power among the government branches, followed by the description of recent constitutional amendments and their outcomes on political power distribution. Then, we address the legal procedures available to counterbalance the misconduct found in each government branch. After that, we assess the judicial branch’s independence in more detail. Finally, we examine oversight agencies and their capabilities and conclude the study.

2. Mongolia in the Comparative Context

This study aims to assess the factors related to the recent trends in democratic decline in Mongolia. As evidenced by the data, most changes were gradual and would require an investigation that starts by the introduction of the 1992 Constitution that institutionalized democracy. In addition, there are formal and informal factors that are involved in the process. Thus, analytically, it is useful to separate de jure and de facto horizontal accountability.

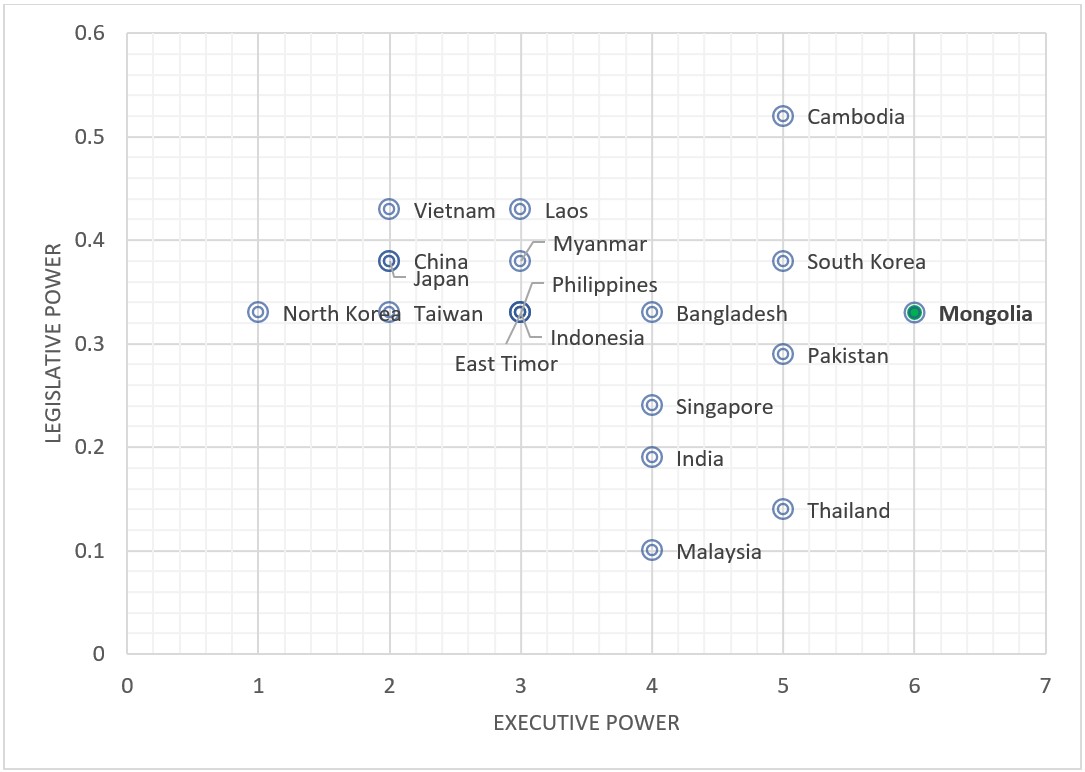

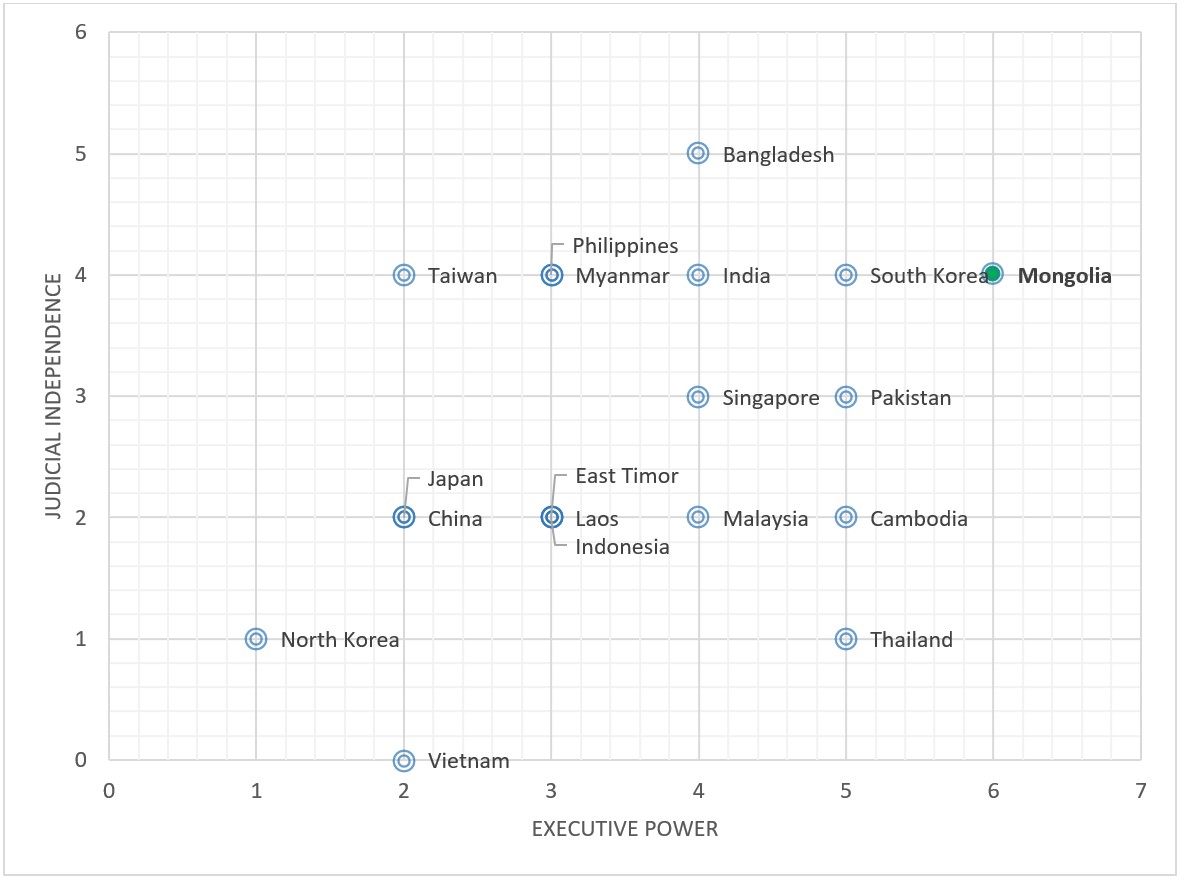

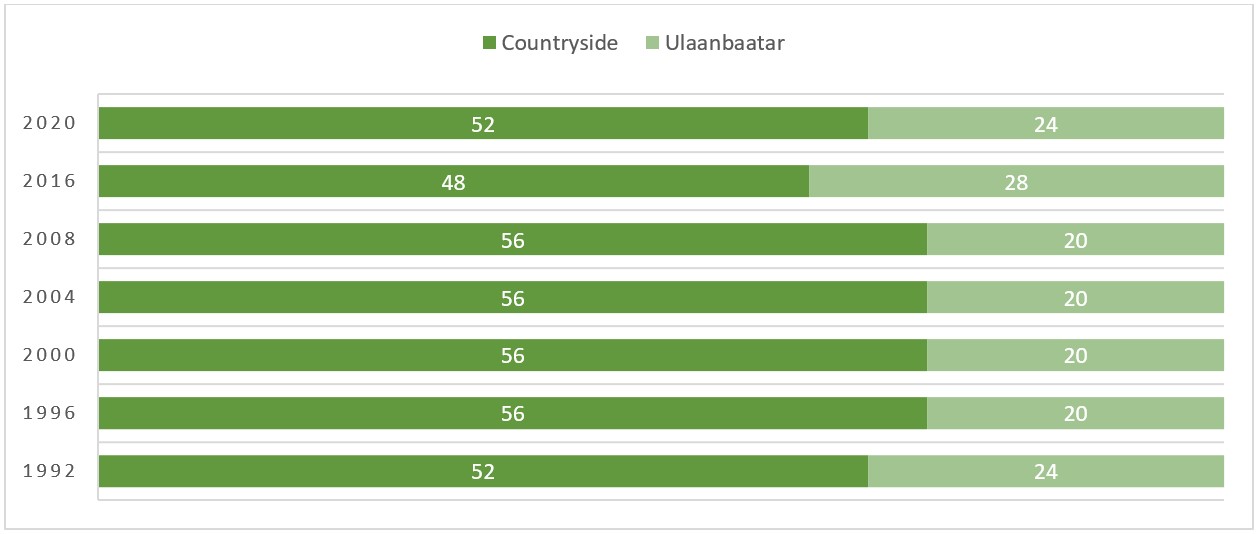

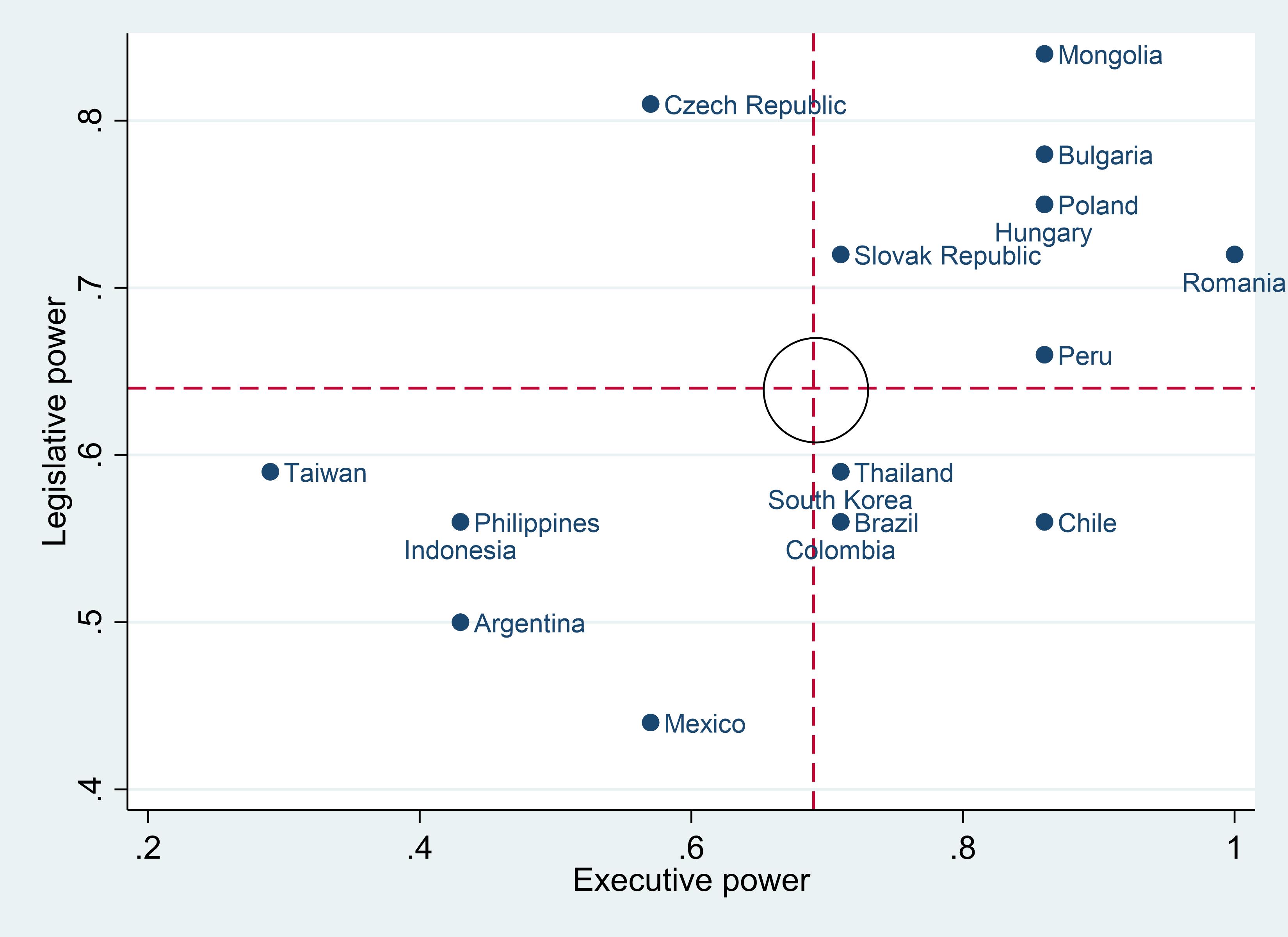

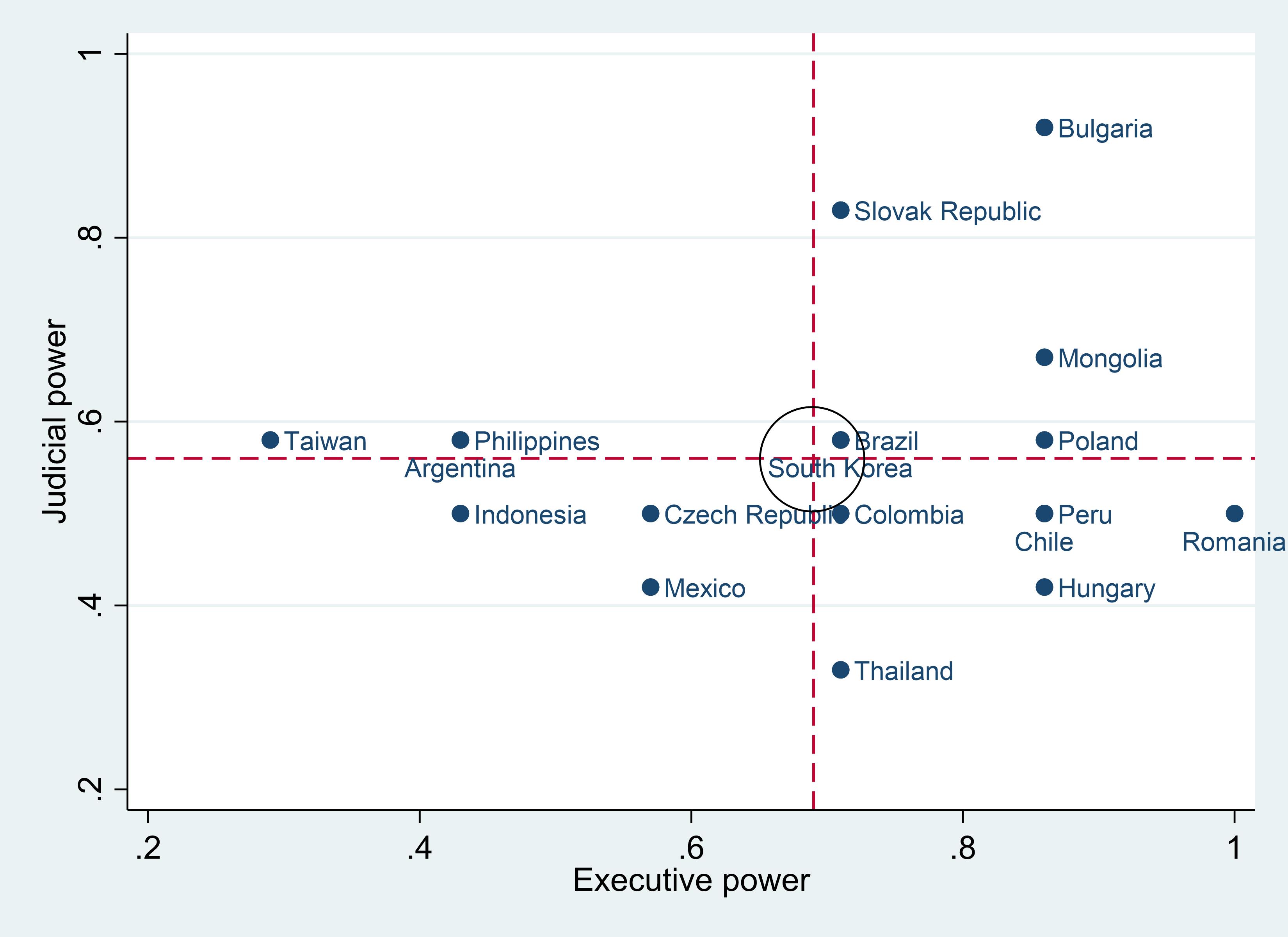

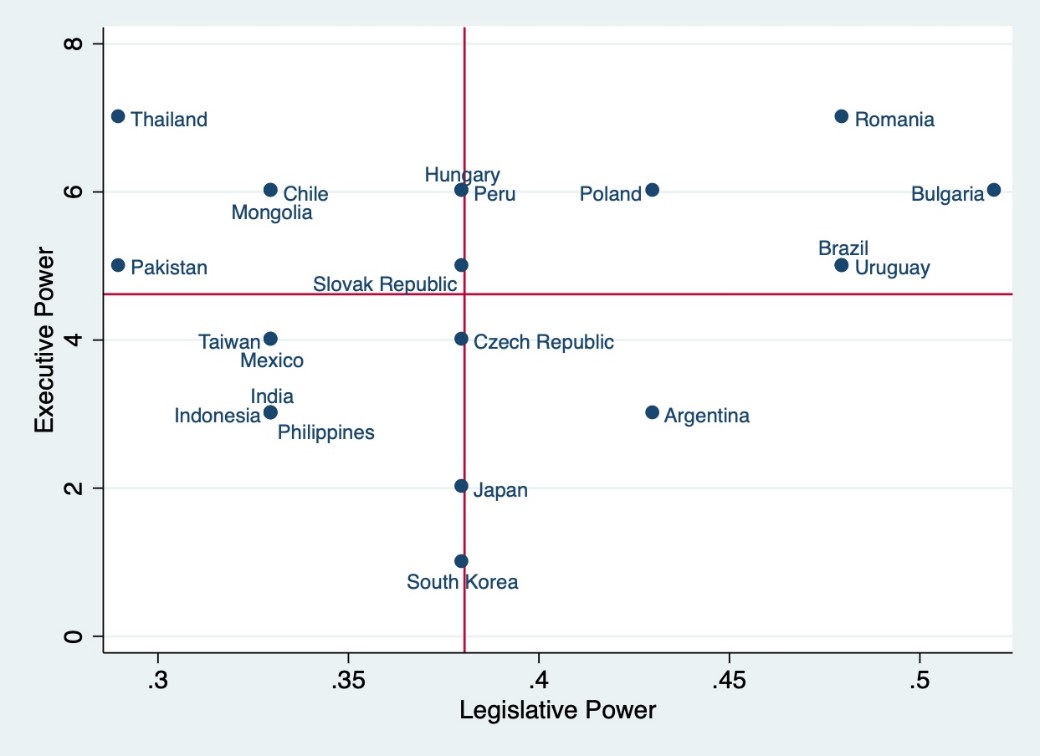

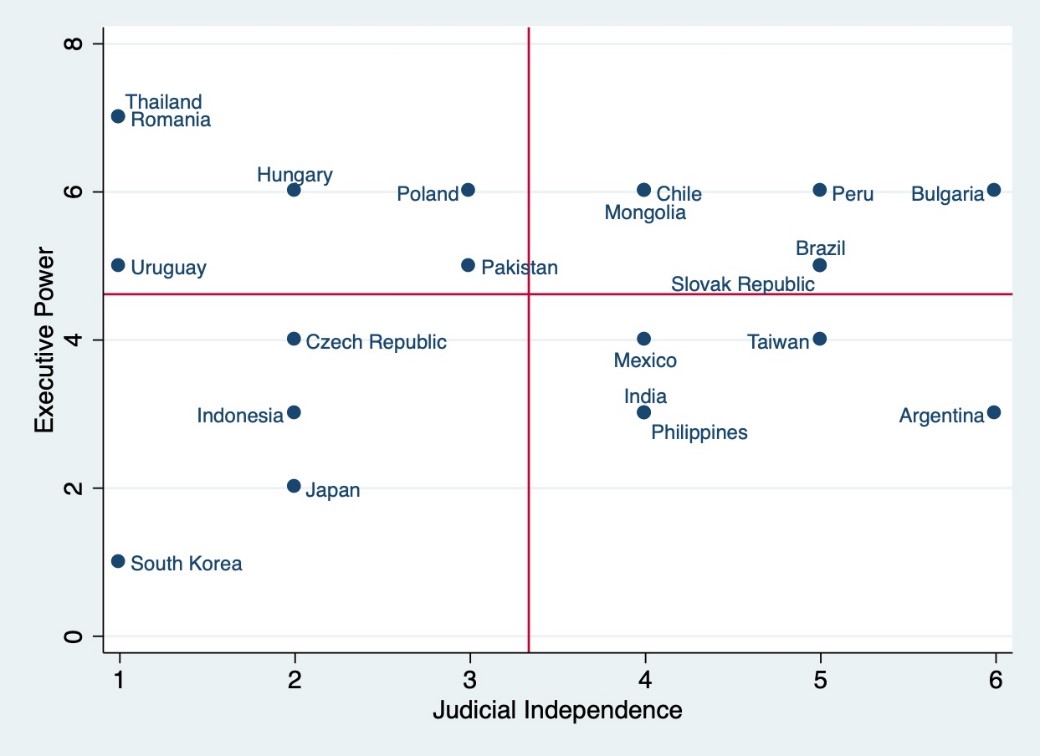

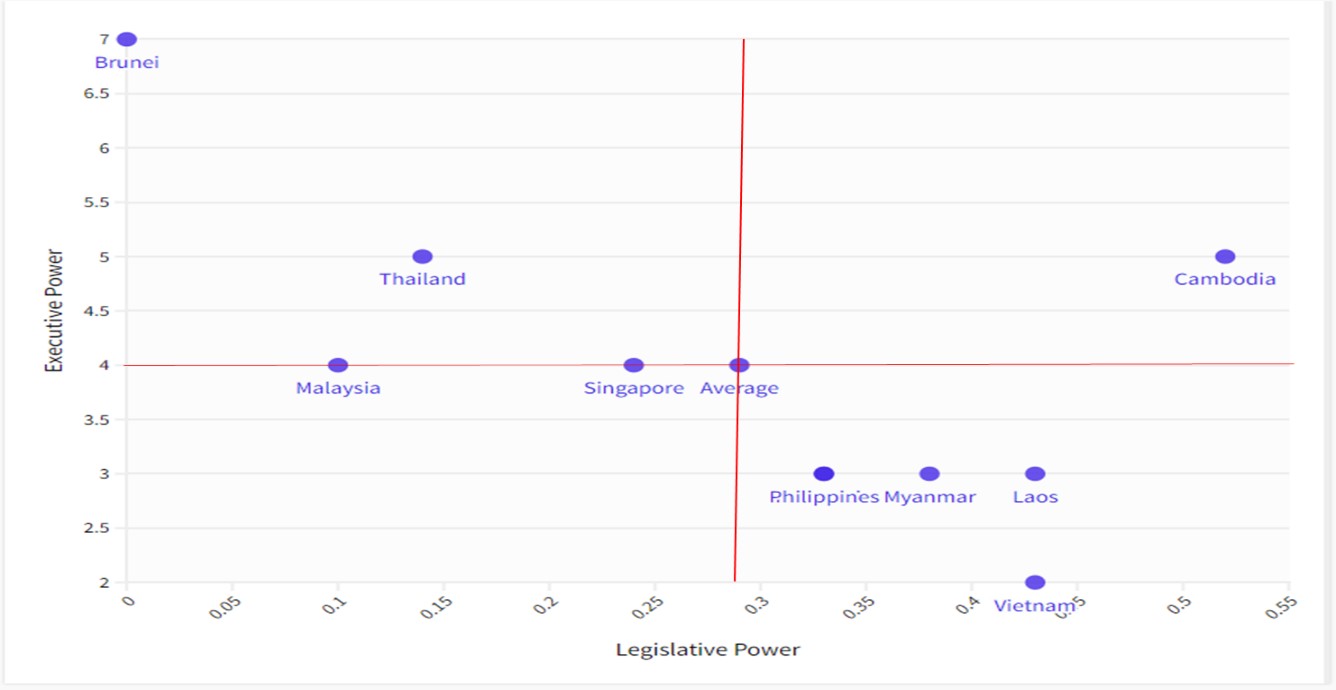

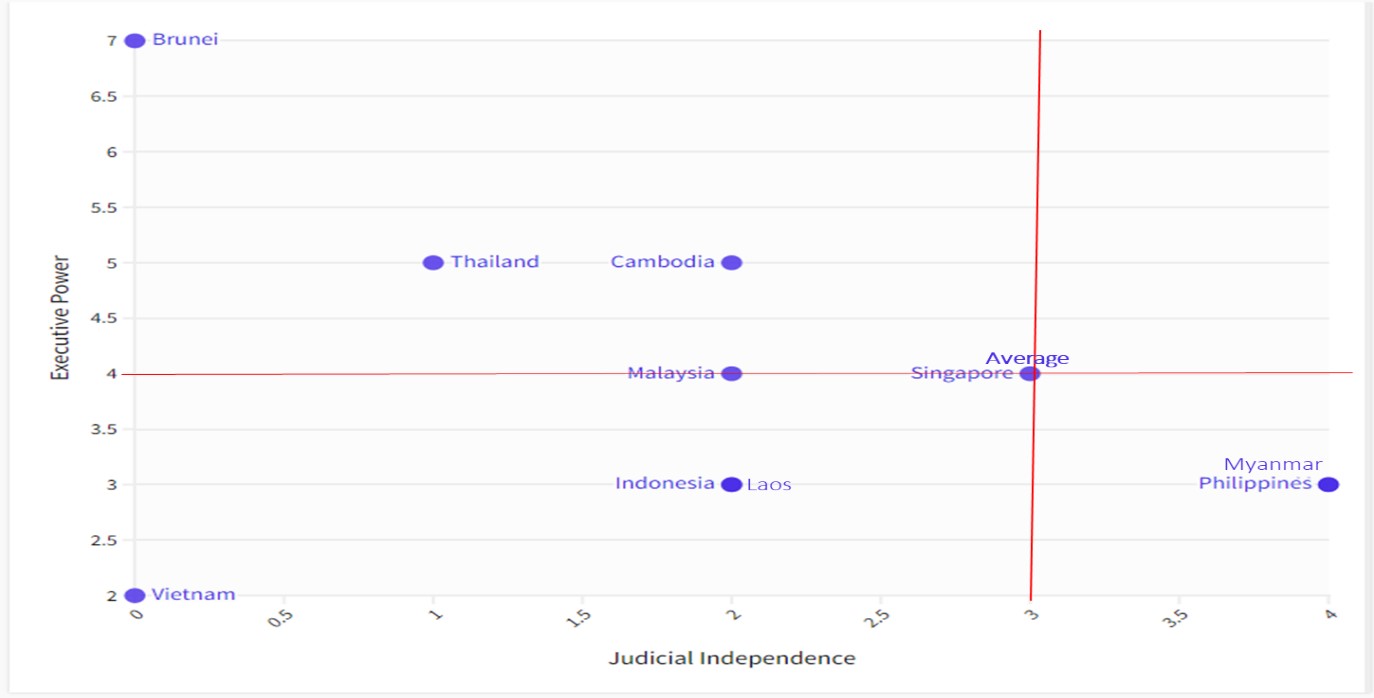

De jure horizontal accountability describes how much power does the Constitution assign to the executive, legislative and judicial branches. It is going to be based on the Comparative Constitutions Project’s executive power indicator, legislative power indicator, and judicial independence indicator (Elkins et al 2022). The indicators based on the 1992 constitution show that the executive power was considerable, scoring 6 on a scale ranging from 0 to 7. The legislative power index was 0.33 on the range of 0 to 1, which indicates less legislative power. Figure 3 shows that regionally, Mongolian executive power is quite considerable, while the legislative power is at an average. It can be seen that the executive power is measured to be more extensive than in Cambodia, South Korea, Pakistan, and Thailand. Moreover, Figure 4 shows that Mongolia scores 4 for judicial independence in the range from 0 to 6, which can be considered average within the region.

Figure 3. Executive Power vs. Legislative Power

Source: Data from the Comparative Constitutions Project

Initially, the Mongolian Constitution introduced a balance between the executive and legislative branches. Thus, prior to amendments, Mongolian legislative and executive powers were relatively balanced. In contrast, the judicial branch’s powers were set to be weaker from the beginning. Further constitutional amendments mainly upset the balance between the executive and legislative powers, leading to the current setting where the legislative branch is dominant, and the other two branches are weak.

Figure 4. Executive Power vs. Judicial Independence

Source: Data from the Comparative Constitutions Project

Given this, it is important to mention that the executive branch in Mongolia is complicated, and in the future analyses, it would be necessary to distinguish the situation before and after the 2019 constitutional amendments. Prior to the amendments, there was an ambiguity about who was the head of the executive branch, as there was a considerable overlap between the president and the prime minister. Specifically, the Constitution explicitly states that the cabinet, led by the prime minister, is “the highest executive organ of the State” (Article 38.1). Yet the president’s role in appointments and legislative initiative implies executive power (Article 33.1). Notably, the 2019 amendment ended this ambiguity by expanding the prime minister’s powers to fully form the cabinet, clarifying that the prime minister is henceforth the head of the executive branch. Future indices may need to reflect this change.

Nonetheless, as we focus on the general situation and consider the president as the head of the executive, it should be noted that the powers given to the president as the national executive are significantly constrained. For that, we are going to break down the executive index in more depth. The index is additive and is composed of seven aspects that measure presence or absence of certain presidential powers. The first aspect measures the power to initiate legislation and is present (Article 26.1). The second involves the power to issue decrees and is also present. Even if the president has the power to issue decrees, the Constitution specifies that a co-signature of the prime minister is necessary for it to be effective (Article 33.1.3). Despite this, in the Mongolian Constitution, both powers are considerably constrained by the president’s lack of budgetary powers. Thus, regardless of the aspirations, it is improbable that any of the presidents’ initiatives will be realized unless they receive legislative support.

The third measurement includes the power to initiate amendments, and it is also constrained, as the president can only initiate constitutional amendments together with “the competent organs or officials with the right to legislative initiative”, or more specifically, “The President, Members of the State Great Hural (Parliament), and the Government (Cabinet)” (Articles 68.1 and 26.1). The fourth measurement covering the power to declare states of emergency is present; however, it is also constrained by the legislature’s decision to endorse or invalidate it (Article 33.1.12). The fifth measurement on veto power is present in Mongolia, but it is limited by the parliament’s ability to override it by two-thirds of its members (Article 31.1.1). The sixth power to challenge the constitutionality of legislation is absent, as this power is reserved to the Constitutional Court (Tsets). The seventh includes the power to dissolve the legislature. This power is also limited as Article 22.2 specifies that the president can only do so in concurrence with the speaker.

Following from this, there are multiple conditions in the Constitution that introduce controls over the presidential power. Particularly, six of the index’s seven powers are present, but all of them are constrained either directly by the legislative branch or indirectly through budgeting. As a result, the veto is the most significant power of the presidency due to the president’s ability to use it repeatedly and bring public attention. Therefore, we suggest that there are limitations in the index’s ability to capture the nuances of the executive power and, as a result, the president’s role in the checks-and-balances can be overestimated. Based on the current indices from the Comparative Constitutions Project, it may seem that the Mongolian executive branch is dominant and is an outlier in the region. Especially, as it shows that the Mongolian president is even more powerful than in South Korea, which has a presidential systеm. However, considering all the constraints included in the Mongolian Constitution and recent amendments, the reality is quite different. Thus, the indices would have to be updated to reflect the new setting.

In the end, the 2019 constitutional amendments have significantly changed the equilibrium established by the 1992 constitution. As a result of the continuous shift of power toward the legislative branch following the 1999/2000 and 2019 amendments, the legislative branch became the most dominant. As a result, the relationship between the three branches became unbalanced with the power predominantly concentrated in the legislature. This imbalance has been further exacerbated by the significant weakening of executive power through the new limits imposed on the presidency.

Specifically, the executive powers of the president have been considerably reduced by an introduction of a single term, higher age, and a reduced role in the judicial appointments. In particular, these changes have decreased the incentives for an active role in inter-branch power relations. In the past, the prospects of re-election made presidents more likely to pursue their own agenda, but since 2019, the shift to a one-term (6 years) presidency has diminished initiatives for political activism. As for the judicial branch, despite the constitutional declaration of its independence, its original design that made higher-level judges and prosecutors political appointees introduced a loophole. Considering a more comprehensive overview of powers, the 1992 constitutional design balanced the executive and legislative powers while leaving the judicial power with an in-built weakness of these political appointments. After the recent amendments though, the balance tilted the following way: