![[Issue Briefing] Six Things You Should Know About Kim Jong Un’s 2018 New Year Address](../images/bg_tmp.jpg)

[Issue Briefing] Six Things You Should Know About Kim Jong Un’s 2018 New Year Address

Global NK Zoom & Connect | Commentary·Issue Briefing | 2018-02-07

Jong Hee Park

Editor’s Note

Kim Jong Un’s 2018 New Year address has been dissected and analyzed numerous times by North Korean experts. In this paper, Jong Hee Park of Seoul National University uses various tools of text analysis to decipher hidden patterns in the 2018 address and then interprets these patterns by comparing this year’s address with previous New Year addresses. In explaining why the vocabulary chosen in the 2017-18 New Year address is very different from the previous ones, Park looks at the facts that Kim Jong Un sees the year 2017 as a turning point from many perspectives.

Introduction

Every New Year’s Day since 1946, North Korean

leaders have issued a New Year address. The address typically contains various messages regarding the internal and external issues facing North Korea, and is usually full of congratulatory remarks for the North Korean people and socialist propaganda against external threats. However, North Korean leaders face different challenges every year and cannot recite the same messages over and over. North Korea has maintained a unique one-man-rule dictatorship in which the Kim dynasty, also known as the Mount Baekdu bloodline, controls the Party, the army and the North Korean people. In the process of legitimizing the ruling by the Kim dynasty after the first generation of Kim Il Sung, North Korea has developed a cult of the supreme leader whose authority and influence far exceeds what modern revolutionary dictators such as Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong, or Fidel Castro envisioned. What makes North Korea unique among existing authoritarian regimes is this cult of the supreme leader.

The North Korea’s New Year address is a statement made directly by the supreme leader. The address contains clear policy goals and slogans that symbolize what North Korean people should achieve during the upcoming year. North Korean people are expected to memorize and recite the supreme leader’s address every year. This makes it one of the most important political texts that show the direction in which North Korea intends to take and this is why North Korean experts make an annual practice of dissecting and re-assembling the wordings in each New Year address. In this report, I will take a mixed approach to the interpretation of the 2018 address. First, I will use various tools of text analysis to decipher hidden patterns in the 2018 address. Next, I will interpret these patterns by comparing this year’s address with previous New Year addresses.

In this report, I would like to highlight six distinct features of the 2018 address that policy makers and experts should pay attention to. I delimit my discussion into these points in order not to reiterate what others have already said such as the length of the address, the peaceful stance toward South Korea, and the proclamation of the completion of the nuclear project although I may revisit some of these issues from a different angle.

1. How Unique is the 2018 Address?

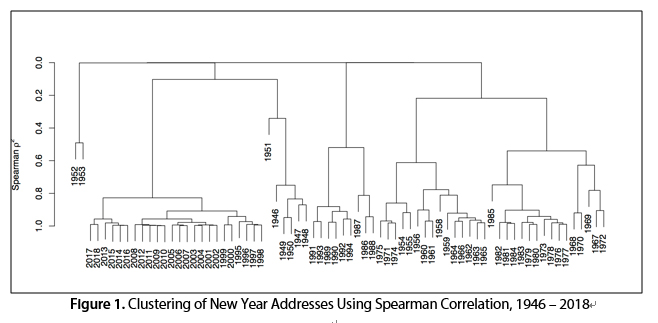

There are many ways to compare the 2018 address with previous New Year addresses. In this report, we employ a simple, intuitive method of comparing unigram words that appear in this year’s address to those from all past New Year addresses beginning in 1946. Then, we use a clustering method to classify each address based on the vocabulary used.

Figure 1 visualizes the clustering of New Year addresses from 1946 to 2018. The second cluster from the left shows the post-1994 cluster covering the Kim Jong Il and Kim Jong Un periods. We can find that the 2017 and 2018 addresses consist of a distinct sub-cluster within the post-1994 cluster. In other words, the vocabulary chosen in the 2017-8 New Year addresses is very different from Kim Jung Un’s pre-2017 addresses (2013-2016) and those by Kim Jung Il. Then, what makes this shift in the vocabulary structure? What constitutes the distinct vocabulary structure of the 2017-8 New Year addresses? We will discuss them in details shortly.

2. A Critical Turn in Military Power

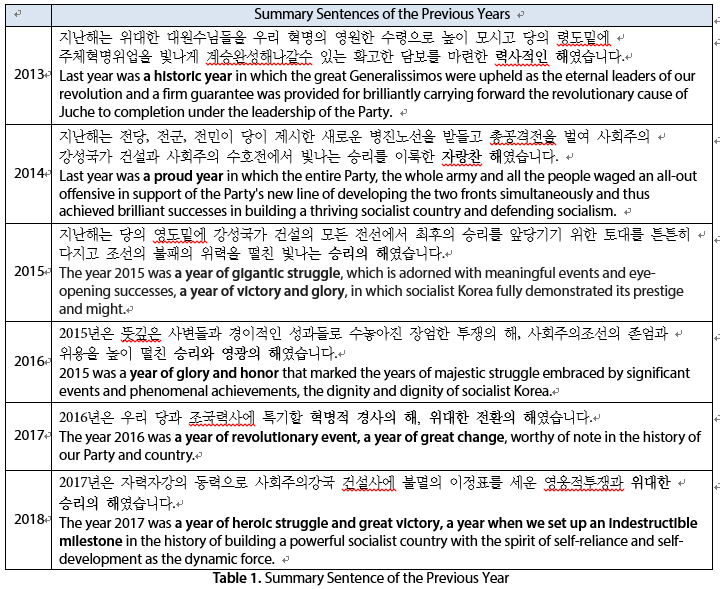

In New Year addresses, North Korean leaders usually praise the achievements they made in the previous year using various excessive adjectives. Thus, the summary statement of the previous year is not something analysts usually pay much attention to. However, when North Korean leaders think that the previous year was particularly important, they do not hesitate to enhance their use of superlatives to emphasize their victories. In that regard, the 2017-8 New Year addresses stand out with regard to their emphasis on the previous year’s achievements.

To get a sense of what the summary sentence usually looks like, we tabulate summary sentences from the six most recent New Year addresses made between 2013 and 2018 in Table 1. Kim Jong Un has issued the regime’s New Year address since 2013. New Year addresses may be put forth by the supreme leader in different forms, including an editorial in the Rodong Sinmum, a co-editorial by three major newspapers (로동신문 Rodong Sinmun, 조선인민군 Joson Inmingun, 청년전위 Cheongnyeonjeonwi), a congratulatory statement, or a speech. All six addresses given between 2013 and 2018 took the form of speech delivered directly by Kim Jong Un. We summarize the key phrases of the summary sentences for the previous years in bold in Table 1.

In order to understand the key phrase of the 2018 address, we need to take one step back and look at the 2017 address. The 2017 address defined 2016 as “a year of revolutionary event, a year of great change.” What constitutes this dramatic shift is North Korea’s transformation into a “nuclear strong state” and a “military strong state.” Specifically, Kim Jong Un mentioned the first hydrogen-to-nuclear test and nuclear warhead explosion tests. Most importantly, Kim claimed that the intercontinental ballistic rocket test launch project had reached the “closing stage.”

This year’s address declared that the dramatic shift in the military defense system had been “completed.” Kim proclaimed that the completion of this shift “set the immortal milestone” in their history toward becoming a socialist strong state. In that sense, the year 2017 was “a year of heroic struggle and great victory, a year when we set up an indestructible milestone” for North Korea. Kim told his people that the long journey of building a socialist strong state had finally passed an “indestructible milestone” by proving the success of his intercontinental ballistic rocket launch test as he promised one year ago. What this all means is that Kim thinks that in 2017, North Korea passed an important turning point in its journey to becoming a strong socialist nuclear power.

3. Nuclear, Nuclear, Nuclear

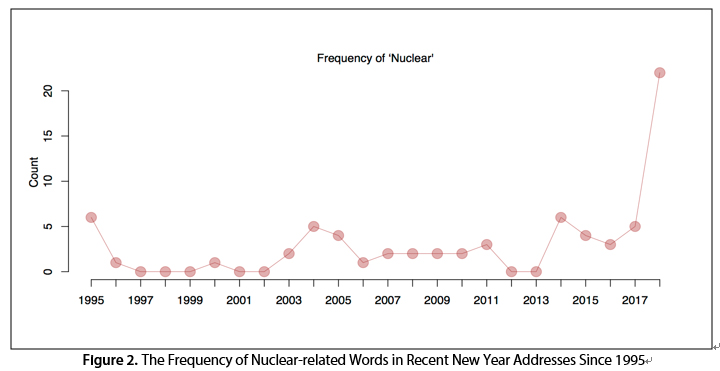

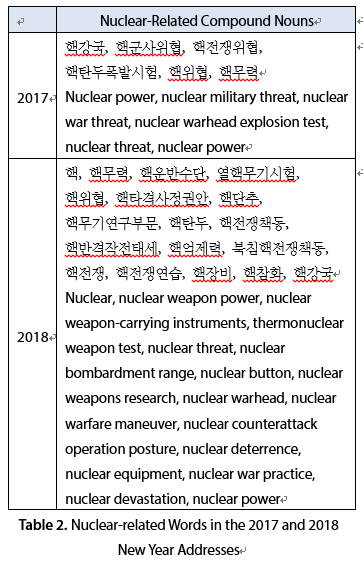

The second distinct feature of the 2018 address is the frequency of nuclear-related words. Figure 2 shows the frequency of nuclear-related words in recent addresses made by post-Kim Il Sung regimes. The 2018 address stands out for the frequency with which nuclear-related words appear.

The high frequency of nuclear-related words in the 2018 address reflects North Korea’s confidence gained following several successful nuclear weapon and ballistic missile systems tests, which culminated in the test of the Hwasong-15 intercontinental-range ballistic missile (ICBM) on November 29, 2017.

Table 2 shows nuclear-related words that appeared in the 2017 and 2018 addresses. A notable difference, besides the increased frequency, is the variety of nuclear-related words, which include such phrases as “nuclear bombardment range” and “nuclear counterattack operation posture.” The diversity of nuclear-related words employed clearly demonstrates the maturity of North Korea’s nuclear weapons development project, as well as the regime’s scope of intention on when and how to use these weapons.

Of particular note is the fact that, for the first time, Kim detailed a kind of nuclear doctrine at the end of the 2018 address as follows:

As a responsible, peace-loving nuclear power, our country will neither have recourse to nuclear weapons unless hostile forces of aggression violate its sovereignty and interests nor threaten any other country or region by means of nuclear weapons. However, it will resolutely respond to acts of wrecking peace and security on the Korean peninsula.

According to this statement, the goal of North Korea’s nuclear project is deterrence, and the regime possesses no offensive ambitions regarding their nuclear weapons system, including their ICBMs. Nonetheless, Kim also stated that their decision to develop a nuclear weapons system proved to be the right one given the changes in international politics in 2017, a reference to the advent of the Trump administration.

However, Kim also acknowledged that the current stage of North Korea’s nuclear program is limited in terms of the number of warheads and actual deployment capabilities, saying that “In the nuclear weapons research and rocket industries, we must accelerate the mass production and deployment of nuclear warheads and ballistic rockets, which have already secured their strength and reliability.”

4. “I am the Supreme Leader!”

The New Year address is a statement from the supreme leader, not the Party. In North Korea’s personalistic (family-controlled) regime, the supreme leader is above the Party and people. In his 2018 address, Kim clearly shows how North Korea is different from other non-personalist autocracies in two instances.

The first instance is his mention of the “nuclear button.” Kim said “the nuclear button is on my office desk all the time.” This statement indicates that Kim alone has unchecked power over the use of nuclear weapons. The second instance is the statement “The United States can never come to war against me and our country.” Kim distinguishes himself from his country for the first time in his New Year addresses since 2013. Considering the fact that the content of a New Year address is carefully prepared and thoroughly edited by his aides, this distinction should be not read as a slip of the tongue. Then, what does “war against me” mean? First, this could indicate a secret operation targeting Kim’s removal such as a decapitation strike by US special forces. Second, it could mean any secret operation or campaign targeting regime change in North Korea by the US, China, or South Korea. By distinguishing himself from North Korea as a country, Kim inadvertently admits that the security of his regime is one thing and that of his country is another.

5. Now, it’s the Economy, People.

Behind the fanfare of North Korea’s nuclear weapon program lies North Korea’s devastated economy and increasing pressure from UN sanctions. If North Korea keeps its promise to limit its use of nuclear weapons to defensive purposes, the North Korean people will never see the utility of nuclear weapons. As Colin Powell said, “nuclear weapons are useless.” Kim probably knows this dilemma very well. He has concentrated the lion’s share of North Korea’s resources into the development and tests of the nuclear weapons system, which has not only diverted resources from other more useful purposes but also invited the implementation of harsh sanctions against North Korea by the international community, including China. As time goes on, the North Korean people will face the bitter consequences of this trade-off, a trade-off that they never approved and never had the chance to approve, in the form of food and oil shortages.

For that reason, Kim repeatedly emphasizes that North Korea needs to make a breakthrough in its economic development in this year’s address. Kim emphasized the goal of making the North Korean economy “independent and self-reliant.” The first step in achieving this goal is to bolster the electric power industry, followed by the metal industry, the chemical industry, the mechanical industry, mining, railroads, and light industry. The priority of this goal indicates Kim’s concerns regarding the recently imposed UN sanctions. However, what makes the current UN sanctions particularly painful to North Korea is China’s compliance. We may infer that the real goal is to make the North Korean economy independent of China.

6. Thank God the Winter Olympics are Coming!

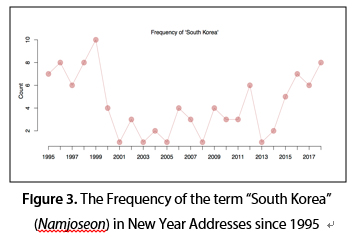

The last thing we cannot miss in this year’s address is the gesture of reconciliation toward South Korea. Figure 3 shows the frequency of the term “South Korea” (Namjoseon) as it appears in New Year addresses since 1995. The 1999 address shows that the term “South Korea” was used ten times, but its use largely indicated the South Korean people, not the government. The term was used then as a form of socialist propaganda encouraging internal struggle against anti-North Korean institutions and laws. In contrast, Kim uses the term “South Korea” eight times in the 2018 address: four times to praise South Korean people’s successful impeachment of President Park Geun-hye and four times to reference the new South Korean government. Most impressively, every use of the term “South Korea” in the 2018 address is either positive or neutral. This degree of positivity towards South Korea is, to my knowledge, unprecedented. The intention behind this positive posture is complicated and highly strategic, as many commentators have already pointed out. However, considering the political importance of the New Year address as a form of instruction from the supreme leader, such a conciliatory posture should not be taken lightly.

The principle North Korea has used for the engagement with South Korea is “among our race 우리민족끼리”(uriminzzokkiri). For that matter, the regime change in South Korea and the upcoming Pyeongchang Winter Olympics provide an ideal opportunity for North Korea to change its stance while saving face. Kim closes his remarks on South Korea by saying “I sincerely hope that everything is going well in the North and South this year.”

Conclusion

Although North Korea already defined the year 2016 as “a year of great revolution, a year of revolutionary turn” in the 2017 address, we should consider the year 2017 as a turning point from many perspectives. First, in 2017 North Korea claimed that they had “completed” the nuclear weapons development project that they consider an “all-purpose sword” for deterrence. It remains to be seen whether this stated confidence is a strategic bluff to buy more time for the actual completion of the project, or a tough warning against any possible provocations intended to test North Korea’s nuclear resolve. However, North Korea has also admitted that their nuclear system is very limited in terms of the number of warheads and deployment capabilities.

Second, the 2018 address clearly demonstrates that North Korea is facing an entirely new type of security challenge now that the Trump administration has come to power in the US, as Trump continues to mull over military options for regime change or destruction of North Korea’s nuclear weapon system. Because of this, North Korea’s rhetoric toward the US has been extremely aggressive, even threatening, stating that now the entire US territory is within North Korea’s nuclear missile range.

Third, despite all of these issues, North Korea has clearly declared what can be considered a North Korean nuclear doctrine, stating it is a “responsible nuclear power who loves peace, and will not threaten any country or region with nuclear weapons.” The two purposes of North Korea’s nuclear weapons, according to Kim, are (1) for use against “threatening hostile forces that violate the sovereignty and interests of our nation” and (2) for use in a counterattack in response to “the act of destroying the peace and security of the Korean Peninsula.” Kim intends two things by this statement. The first goal is to send a clear signal to the US that any type of military option taken against North Korea will be countered with nuclear weapons. The second goal is to ask the international community (and the US in particular) to recognize North Korea as a nuclear power like India, Israel, and Pakistan.

However, North Korea must be well aware that no county has been recognized as a nuclear power while threatening the US with their nuclear weapons. The second goal is nothing but far-fetched, wishful thinking. The true message of the statement is to drive home the first point: nuclear counterattack against any type of aggression.

The launch of Hwasong-16 convinced the CIA that North Korea’s ICBMs have nearly reached the completion stage. Recently, CIA Director Mike Pompeo advised the US President that the US has a

three-month window during which to preempt North Korea’s ICBM plans. North Korea’s hasty declaration of its nuclear success (originally made on November 29, 2017) and nuclear doctrine (on January 1, 2018) is a signal to the US that there is no window for a preemptive strike and any strike will be countered by military actions, possibly with nuclear warheads.

In 1998, the International Olympic Committee revived an ancient Greek tradition of the “Olympic Truce,” or “Ekecheiria,” that calls upon all nations to observe the Truce. It is a historical irony that an Olympic Truce has been called for between the US and North Korea, who signed the armistice agreement that halted the Korean War in 1953, for the upcoming Pyeongchang Olympics. The Vice President of the US and the Chief of the Supreme People’s Assembly of North Korea will visit Pyeongchang as the delegate heads of each country. So far, there are no signs of direct talks and negotiations between the two sides. It appears that the situation has reached a stalemate, and this stalemate in turn appears precarious because of the US’s (actually, the CIA’s) self-imposed deadline of a “March window.”

This stalemate should be broken before any party chooses the irreversible option of punching the other in the face first – either via North Korea’s bombing of Guam or the US’s “bloody nose” operation - in order to avoid a catastrophic outcome that could kill millions of innocent lives in the Korean Peninsula and derail the improving global economy.

The situation calls for someone to play the role of “honest broker.” It could be South Korea, China, Russia, EU, the United Nations, or any individual that can effectively deliver truthful information to both sides and convince top decision makers in both countries to choose the best available option that ensures mutual safety and benefits. There is no doubt that South Korean President Moon has the highest stake in solving this stalemate. ■

Author

Jong Hee Park is currently employed as Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Seoul National University. His research interests include political methodology and international political economy. He received his Ph.D. from Washington University in St. Louis.

Center for North Korea Studies

Center for National Security Studies

Global NK Zoom & Connect

Global NK Zoom & Connect

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20240419123938102197065(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections

Niranjan Sahoo | 2018-02-07

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2024032815145548472837(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?

Ken Godfrey | 2018-02-07