![[Korea-Japan Joint Work on the World 2050] ⑤ The Long-Term Vision for ROK-Japan Economic Cooperation in the Era of De-Globalization and Shrinking](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/2025040117952395366503.png)

[Korea-Japan Joint Work on the World 2050] ⑤ The Long-Term Vision for ROK-Japan Economic Cooperation in the Era of De-Globalization and Shrinking

Working Paper | 2025-03-12

Junghwan Lee

Professor, Seoul National University

Junghwan Lee, Professor at Seoul National University, acknowledges the absence of immediate economic incentives for deepening South Korea-Japan cooperation in trade and investment. However, he argues that collaboration is essential due to shared structural challenges, particularly demographic decline and the resulting loss of global economic influence. Lee highlights key areas for cooperation, including economic security, joint investments in third-country markets, and strategic engagement with the Global South. He also underscores the potential for long-term joint investment in North Korea’s economic development, contending that such collaboration could serve as a vital strategy for revitalizing both economies in the future.

I. Introduction

Economic cooperation between the Republic of Korea (ROK) and Japan is no longer just about promoting trade and investment. In the era of U.S.-China competition, joint efforts to respond to the securitization of the economy have been much discussed recently. It is not surprising that the discussions on bilateral economic cooperation at the 2023 Korea-Japan summits have focused on economic security policy cooperation. Cooperation in economic security policy is arguably one of the most important ways for the ROK and Japan to dually respond to recent geopolitical and geoeconomic global structural changes. Furthermore, it is necessary to move beyond economic security policy cooperation to produce a joint response to effectively overcome the political economic trends of de-globalization.

However, from a more long-term perspective, economic cooperation between the ROK and Japan should also consider that both countries are out of the growth stage. Even if the unpredictable situation of U.S.-China competition gets lifted in any form, this will not change the post-growth nature of both countries’ economies. The presence and influence of both countries in terms of economic size will shrink amid demographic changes of a shrinking population and aging. In this context, the ROK and Japan should find ways to maintain their competitiveness in the global economy, and to do so, they will need to pool their wisdom. This article is intended to propose the long-term direction of economic cooperation between the ROK and Japan.

II. Challenges to the ROK and Japan around 2050

1. U.S.- China Competition and De-globalization

While China’s economic growth has long been expected to challenge the U.S.-led international order, the conflict was not realized until the 2000s. However, in the 2010s, as China’s challenge to the U.S.-led international order became more explicit, the United States gradually adopted a more proactive stance in response. The U.S.-China trade conflict, sparked by the first Trump administration, soon became linked to the two countries’ high-tech competition (Blackwill and Fontaine 2024). This trend has intensified under the Biden administration. Both decoupling and de-risking imply the balancing posture of the U.S. toward China’s economic growth and technological autonomy.

The U.S.-China competition has led to interdependence’s weaponization. Interdependence is no longer mutually beneficial in the economic securitization initiated by the U.S.-China competition (Farell and Newman 2023). Trade, energy, and resource dependence have become political weaknesses in recent years. For the ROK and Japan, which have developed as trading nations in the liberal international order, economic securitization has meant a deterioration in the international economic environment.

However, U.S.-China competition is not the sole reason for de-globalization. The current trend of de-globalization had already arisen after the Global Financial Crisis in the late 2000s (James 2018). Most countries have seen a decline in the preference for free trade policies and a strengthening of political voices in favor of domestic protectionism. The preference for de-globalization politics, linked to the rise of populism worldwide, is symbolized by twice Trump’s wins in the U.S. presidential elections (Gusterson 2017).

The U.S.-China rivalry is also expected to be quite prolonged. However, even if it ends sooner than expected in any form, de-globalization is likely to remain robust in the longer term. In the post-war world order, the ROK and Japan were not active supporters of protectionism or de-globalization trends, and it is clear that the current trend of de-globalization is also harmful to both countries’ future.

2. Low Growth and Mature Economies

Korea and Japan are also similar in that both countries are in a condition of low growth. Japan’s low growth has been a phenomenon for more than 30 years, but unlike the cyclical nature of the 1990s, it has stemmed from structural problems in the Japanese economy since the 2000s. The escape from low growth through structural reforms that eliminate inefficiencies in Japan’s economic structure is a persistent theme in Japanese political economic discourse (Gao 2000). However, even with structural reforms, Japan’s maximum potential growth rate is lower than in the past. It is because Japan’s low growth is now originated from the maturity of its economic structure.

The Japanese story is repeated in the ROK. The ROK’s slide into low growth has been much more rapid. The ROK’s and Japan’s per capita have become similar in recent years because the ROK has experienced relatively high growth since the 1990s, while Japan has been sluggish. However, the fact that the ROK’s growth rate was lower than Japan’s in 2023 is an important indicator. It means that the ROK is following Japan’s experience of transitioning to low growth.

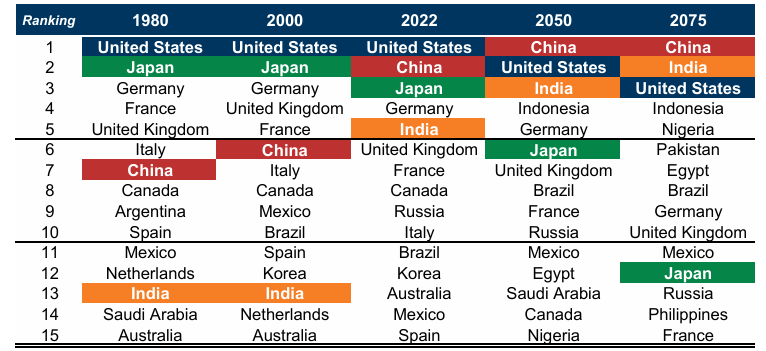

The low growth of the ROK and Japan may not be a problem, as it has stemmed from the maturation of their economic structures. However, it raises the question of whether the current low growth status can be sustained in the face of population shrinking and aging. Furthermore, the ROK and Japan will inevitably become less significant in the future global economy regarding their quantitative portion. By 2050, Japan is projected to drop to the sixth largest economy in the world, and the ROK will struggle to maintain its current top 15 ranking ([Figure 1]). Higher economic growth rates in emerging economies are expected to drive this. Though uncertainties remain about the economic prospects of these economies, their growing presence in the global economy is inevitable.

[Figure 1] Projections for the World’s Largest Economies (measured in USD)

The ROK and Japan share a common future challenge in that it will be difficult to maintain the current low growth rate due to demographic changes, and it will be challenging to maintain their position in the global economy. Therefore, they are in the same situation; they must innovate their social structures and actively engage with emerging economies.

III. ROK-Japan Economic Cooperation, Old and New

The ROK-Japan economic relations have shifted from a “vertical asymmetrical relationship” to a “horizontal symmetrical relationship” like the overall ROK-Japan relations (Kimiya 2021). This is a classic example of the “flying geese” model (Kojima 2000). Japan’s commercial loans and foreign direct investment in the ROK’s early industrialization are highly critical. The ROK-Japan economic cooperation since the 1960s has shaped the asymmetrical relationship between the two countries. Capital investment and technological cooperation from Japan play an important role in the ROK’s economic development (Abe 2015).

However, economic asymmetries between the ROK and Japan were mitigated due to Japan’s prolonged recession and the ROK’s economic success. The ROK’s trade dependence on Japan has steadily decreased as the country’s industrialization has progressed. As the ROK successfully shifted from a labor-intensive industrial structure to the same type of industrial structure as Japan, the level of competition in the global market increased. This trend results from the ROK’s effective strategic choices in economic development. With the development of global value chains, the direct trade and production relationship between the ROK and Japan has become less direct (Kim 2015).

Economic cooperation incentives are not clear from the perspective of trade and investment. New momentum in bilateral economic cooperation is rarely seen in the symmetrical relationship between the ROK and Japan. Apart from high interdependence at the firm level, it has become difficult to find logic and incentives for the two governments to cooperate in the economic sphere.

However, governments should adopt new perspectives on their rationales for bilateral economic cooperation. Rather than emphasizing increasing trade and investment, the ROK and Japan can cooperate to respond to challenges related to de-globalization and shrinking. The ROK and Japan share these challenges nowadays. The new direction of ROK-Japan economic cooperation should focus on addressing these common challenges together.

IV. Cooperation Against De-Globalization

First, the ROK-Japan economic cooperation should be given to the two countries’ joint response to the de-globalization trend amid the US-China strategic competition and efforts to restore the liberal order of the global economic architecture.

1. Supply Chain Stability

In the era of the U.S.-China competition, the securitization of the economy has become a global trend. The re-emphasis on shrinking risks and increasing one’s capabilities in economic and industrial structures is now prevailing in most countries’ policies as a name of economic security policies (Drezner et al. 2021). There are common characteristics in economic security policies: 3P. Most governments’ economic security policies are organized as protection, promotion, and partnership.

How is the ROK-Japan partnership in economic security policies well incorporated with their own protection policy and promotion policy? Between the ROK and Japan, partnership for protection is supply chain cooperation, whereas partnership for promotion is cooperation in developing future emerging technologies. Both partnerships have been incorporated in all statements of the bilateral summit between President Yoon and Prime Minister Kishida and the trilateral summit among the U.S., the ROK, and Japan in Camp David (Office of the President 2023a; 2023b; 2023c).

Partnerships for protection are likely to be developed comparatively faster. The ROK and Japan share the same condition in the global production systern: high foreign dependence on energy and raw materials. Since the 2000s, the PRC has been active in weaponizing its dominant position in the supply chain. Japan experienced a Chinese rare earth embargo during the 2010 Senkaku dispute, and the ROK experienced Chinese economic retaliation following the deployment of THAAD in 2016. Supply chain stability for Japan and the ROK aims to avoid unilateral dependence on China. However, in the context of de-globalization, the policy target of securing supply chain stability is expanding. Measures such as diversifying import lines, domestic stockpiling, and strengthening domestic production systerns are required to secure supply chain stability. Diversification of import lines, joint stockpiling, and mutual supply cooperation for items highly dependent on overseas markets have become a core part of cooperation for economic security policies between the ROK and Japan. Both governments have already agreed to strengthen supply chains for hydrogen and ammonia (The Japan Times 2024).

In addition, the two governments agreed that both countries’ corporations would jointly invest in a third-country project funded by a government financial organization and work together to build a supply chain (METI News Release 2024). In economic security, supply chain cooperation is one of the fastest moving and most necessary aspects of cooperation. Furthermore, joint measures to respond to energy supply chain instability, secure sea lane stability, and establish a hydrogen economy are being explored as bilateral functional cooperation between the two governments.

2. New Global Rule Setting

Recent global economic security policy trends are also linked to a boom in the state’s active involvement in industrial policy. In most industrialized countries and emerging economies, deregulation and neoliberal economic policies are no longer welcome. While this is linked to the growing political preference for de-globalization in many countries, the view that the state should be more active in securing future national competitiveness is more widely accepted (Mazzucato 2021). The state’s active involvement in economic and industrial policy, often referred to as New Industrial Policy, is in line with recent trends in technological innovation (Tyson and Zysman 2023).

Developed and emerging economies seek to increase their technological competitiveness in the newly emerging advanced technologies. The global economy’s central industries and core technologies fluctuate with technological innovations. Both the ROK and Japan are making government investments in emerging technologies, and there has been recent talk of bilateral cooperation on emerging technology development.

Another dimension of bilateral cooperation on emerging technologies is cooperation in shaping international norms for emerging technologies. Digital economization, coupled with the development of emerging technologies in cyber and AI, makes it challenging to deal with traditional trade rules. Moreover, with the WTO, the center of traditional trade rules, already dysfunctional, international norms that ensure the stable use of emerging technologies are still under discussion. The problem is that the U.S. and China, which should play a central role in shaping international norms for emerging technologies, are engaged in mutually exclusive norm-setting efforts. While many experts argue that a bilateral agreement on emerging technologies would be the most effective and necessary, there is widespread skepticism about its feasibility (Huq 2024).

The ROK and Japan are working together to join the U.S. and developed countries to form international norms. Significantly, the G7 has recently become a critical stage for forging international norms on AI and cyber technology. As a member of the G7, Japan has significant positional power in the G7-centered international norm formation process. Although the ROK is a partner country of the G7, it has a competitive edge in emerging technologies. Under increasing uncertainties of the Trump administration, the G7 platform should be complemented by cooperation among like-minded countries. To Japan and the ROK, the EU (and the UK) is the crucial partner in the global norm-setting. It is also necessary to advance the ROK-Japan bilateral cooperation in these areas.

V. Cooperation Against Shrinking

In the 21st century, the ROK and Japan are unlikely to maintain their positions in the global GDP rankings. Various ways to maintain national competitiveness should be explored, and cooperation strategies between the ROK and Japan could be considered.

1. Technology Development Cooperation for Responding Tasks

Developing emerging technologies are also considered significant in the economic security policies of most countries. Cooperation on technological development has been an essential topic in the discussions on economic security policy cooperation between the ROK and Japan. However, cooperation on emerging technology development between the two countries is a long-term challenge compared to supply chain cooperation. There are clear complementarities as well as competitiveness in many industrial sectors of the two. It is not easy for two countries that have been competing in the global market to establish large-scale cooperation on developing emerging technologies, which will be a key part of their industrial competitiveness in the future, in a short period.

However, there is a lot of space for the ROK and Japan to work together on how to utilize emerging technologies. While emerging technologies are a source of future national competitiveness in themselves, they are also a method to respond to the demographic challenges in both countries. Increased care needs due to a growing elderly and labor shortages due to a declining working-age population are among the biggest concerns for the future of both countries. There is not enough labor supply to meet the growing demand for social services caused by the elderly. There is a broad consensus among policymakers that the working-age population should be directed to the more productive sectors. Finding ways to not only meet the care needs of the elderly but also to effectively maintain society in the face of a shrinking labor supply is a challenge for both the ROK and Japan in an era of population decline.

The idea of using emerging technologies to compensate for the labor shortages we face in an era of shrinking populations is an old one. But for the ROK and Japan, it needs to be done now. Of course, a technocratic view in which technological innovation completely replaces labor is not practical (Acemoglu and Johnson 2023). Instead, new technologies such as AI and cyber have recently emerged as important in maximizing labor productivity.

The ROK and Japan can cooperate in developing technologies such as AI and cyber, but there is also a lot of room for cooperation in using technology to respond to various societal challenges in the era of population decline. This is where the Strategic Innovation Program (SIP), which Japan has been promoting for over a decade, comes into play (Cabinet Office 2024). Rather than focusing on developing specific technologies, SIP emphasizes the convergent use of technologies to respond to various social challenges. Over the five-year period from 2023 to 2027, a total of 14 technology development issues were targeted for support under the SIP, including building a sustainable food chain, building an integrated healthcare systern, building an inclusive community platform, building a platform to realize learning and working methods in the era of the pandemic, building a maritime security platform, building a smart energy management systern, building a circular economy systern, building a smart disaster prevention network, building a smart infrastructure management systern, building a smart mobility platform, developing basic technologies and rules for the expansion of human-collaborative robots, developing basic technologies and rules for the expansion of the virtual economy, promoting the application of advanced quantum technologies to social problems, and building an ecosystern for innovation and incubation of material commercialization. These selected tasks have in common the use of advanced technologies to solve various social problems such as aging, population decline, and local extinction.

Technological cooperation between the ROK and Japan can be pursued not only in developing technologies themselves but also in finding wisdom on how to utilize technology for social tasks in the age of declining population. Using the SIP as a platform, government officials from both countries must discuss the possibilities of cooperation for problem-based technology utilization cooperation between the ROK and Japan.

2. Deepening Ties with the Global South

As emerging economies, represented by the Global South, become increasingly important, Korea and Japan seek to deepen economic ties with them through trade, investment, and infrastructure development cooperation. The Global South countries have again raised North-South issues without falling into either side of the US-China rivalry (Ito 2023). To Japan, the rise of Global South demands the necessity of developing their ODA and infrastructure investment policies. It would be one of hedging strategies against US-China competition (Office of Policy Planning and Coordination on Territory and Sovereignty 2024).

Japan’s problem is that it is difficult to maintain the level of quantitative expansion in ODA and infrastructure investment in emerging economies to counter China’s aggressive offensive over the past decade. Japan and the ROK must further strengthen their cooperation in ODA and infrastructure investment to target emerging economies. Joint investment in infrastructure markets in third countries has always been discussed as a method of bilateral economic cooperation.

As the ROK and Japan seek to develop ties with emerging economies, knowledge-sharing projects are becoming essential. As leading examples of countries that have experienced growth through connectivity to the global market, sharing their development experiences with countries seeking similar growth paths will help enhance their engagement with emerging economies. In the future, the ROK and Korea could collaborate to provide knowledge-sharing projects to emerging countries.

VI. Building Roadmap for Future Development Cooperation in North Korea

Since the maturation of their economic structures, both the ROK and Japan have had experience in pursuing wealth acquisition through increased overseas investment. Even now, investment in emerging economies in the Global South is essential for both countries to maintain their economic influence in the global economy. However, a space near both countries could be a promising investment area for the future: North Korea. North Korea remains an undeveloped region close to the ROK and Japan. Due to geopolitical considerations, the ROK’s and Japan’s involvement in developing these regions is currently not feasible. However, from a longer perspective, North Korea could provide momentum for economic revitalization in both countries. If North Korea is integrated into the international community and connected to global markets, the ROK and Japan will have the closest source of low-wage, skilled labor for investment.

Even if development cooperation in North Korea is not immediately feasible, Japan and the ROK can work together to devise a roadmap for it. It is possible to discuss the creation of a joint investment fund between the ROK and Japan. The ROK and Japan could consider jointly investing in the North Korean Development Trust Fund or Northeast Asian Development Bank, which had been considered a policy tool for opening up North Korea to the ROK in the past.

North Korea’s infrastructure development is believed to require vast financial resources. When North Korea opened up, calculations in the 2010s estimated that it would need KRW 306 trillion in infrastructure investment in the first 10 years (Park 2019). The primary responsibility for financing this is obviously the North Korean government, but it is unlikely that North Korea will be able to take on this role. In the long term, as North Korea opens up to the world and becomes more connected to global markets and international finance, it will be necessary for Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and private banks to provide development cooperation funding and develop public-private partnership financing. However, North Korea’s current lack of connectivity to international financial markets and unfamiliarity with international financial norms make it difficult for the country to move directly to this type of financing. Given the unique nature of inter-Korean relations, the ROK is considered the most likely non-North Korean source for infrastructure investment. However, it is not realistic to expect the ROK to cover all or even most of North Korea’s infrastructure construction needs.

It has been discussed that the most realistic international cooperation for infrastructure investment in North Korea would be establishing a multi-donor trust fund funded by relevant countries, including the ROK. The idea is to establish a North Korea Development Trust Fund and entrust its management to the United Nations Development Group and the World Bank (Lee 2014). The North Korea Development Trust Fund is the most realistic multilateral international cooperation option for infrastructure investment in North Korea in the post-nuclear era, before North Korea’s membership in the IMF is realized.

Multilateral trust funds are funds contributed by multiple donors for specific development purposes and projects and administered in consultation with the government of the recipient country through an international management agency, usually a United Nations organization or an international financial institution such as the World Bank, which is designated as a management agency to manage the fund and support projects. Since the 2000s, it has been used to fight hunger, improve health, and reconstruct conflict zones in poor countries under the management of the United Nations Development Group or the World Bank.

In addition to the multilateral framework centered on the MDBs, international cooperation on infrastructure investment in North Korea can also be organized at the regional level. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), which is currently no different from other MDBs, has implications for international cooperation on infrastructure investment in North Korea because it was founded as a regional cooperation framework with a non-economic political goal of supporting the transition from socialism in the former Eastern Bloc countries (Yoon 2014).

Discussions on establishing an MDB specialized for the Northeast Asian region have been ongoing since the 1990s, with talk of establishing a Northeast Asian Development Bank. The need for additional international financing for development needs in Northeast Asia was discussed during the post-Cold War regionalism boom, and there was considerable consensus on the need for a Northeast Asia Development Bank in the early 1990s, as proposed by former ROK Prime Minister Nam Deok-woo and the Tokyo Foundation in Japan. In the early 1990s, China’s Northeast and Russia’s eastern regions were underdeveloped and not sufficiently resourced to meet their development finance needs. However, after China’s economic growth and Russia’s stabilization, no Northeast Asian countries were eligible except for Mongolia. In the 2000s, the ROK reactivated the idea of a Northeast Asian Development Bank and discussed using it to finance North Korean development (Zang 2014).

Although it has been discussed as a regional cooperative financing organization for development cooperation in North Korea, the Northeast Asian Development Bank concept is unlikely to play a leading role and differentiate itself from other MDBs in supporting North Korea. However, exploring a regional institutional framework in addition to the multilateral framework for international cooperation on infrastructure investment in North Korea is significant in diversifying cooperation. If North Korea returns to the international community, discussions on linking regional development initiatives to North Korean development will evolve. While regional development initiatives may compete in North Korea, it will be necessary to establish a cooperative framework to effectively integrate regional development initiatives into infrastructure investment in North Korea. While unrealistic in the short term, a strategic joint contribution between the ROK and Japan to the North Korea Development Trust Fund or the Northeast Asian Development Bank is a long-term consideration.

VII. Conclusion

Since the normalization of diplomatic relations in 1965, economic cooperation has been a central pillar in the development of the ROK-Japan relations over the past 60 years. However, economic cooperation focusing on promoting investment and trade has become less effective as their economic relationship has changed. Instead, cooperation on economic security policies has emerged as a central theme in the current U.S.-China rivalry, and cooperation on economic security policies is likely to drive bilateral economic cooperation for the foreseeable future.

In the longer term, however, the ROK and Japan will also need to jointly address concerns about their diminishing presence in the international community stemming from low growth and demographic change. To this end, technological cooperation to address social tasks arising from demographic decline and cooperation to increase engagement in the Global South will be crucially considered. Furthermore, although geopolitically unrealistic at this moment, joint efforts to bring North Korea into the international community should not be forgotten.■

References

Cabinet Office. “Cross-ministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion Program (in Japanese).” https://www8.cao.go.jp/cstp/gaiyo/sip/index.html (Accessed December 31, 2024).

Goldman Sachs. 2022. The Path to 2075 — Slower Global Growth, But Convergence Remains Intact. https://www.goldmansachs.com/.../report.pdf (Accessed December 31, 2024).

Huq, Aziz. 2024. “A World Divided Over Artificial Intelligence: Geopolitics Gets in the Way of Global Regulation of a Powerful Technology.” Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/.../world-divided-over-artificial-intelligence (Accessed December 31, 2024).

Ito, Tory. 2023. “India’s ‘Global South’ Diplomacy and How Japan Should Respond.” http://ssdpaki.la.coocan.jp/proposals/145.html (Accessed December 31, 2024).

METI News Release. 2024. “Japan-Korea Director-General Meeting Held in the Field of Hydrogen and Derivatives, Including Ammonia.” February 16. https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2024/0216_001.html (Accessed December 31, 2024).

Office of the President. 2023a. “The Spirit of Camp David: Joint Statement of Japan, the Republic of Korea, and the United States.” August 13. https://www.president.go.kr/newsroom/press/yeE9qWlT (Accessed December 31, 2024).

______. 2023b. “Joint Press Conference on the Korea-Japan Summit.” March 16. https://www.president.go.kr/president/speeches/qBjKQLZX (Accessed December 31, 2024).

______. 2023c. “Joint Press Conference on the Korea-Japan Summit.” May 8. https://www.president.go.kr/president/speeches/fVLH4DuS (Accessed December 31, 2024).

The Japan Times. 2023. “Tokyo and Seoul to set up hydrogen and ammonia supply chain: report.” November 10. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/business/2023/11/10/japan-south-korea-ammonia-hydrogen/ (Accessed December 31, 2024).

Tyson, Laura and Zysman, John. 2023. “The New Industrial Policy and Its Critics.” Project Syndicate. https://www.project-syndicate.org/.../the-case-for-new-industrial-policy.

■ Junghwan Lee is Professor at the Department of Political Science and International Relations, Seoul National University.

■ Typeset by Sheewon Min, Research Associate; Chaerin Kim, Research Assistant

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | crkim@eai.or.kr

Center for Japan Studies

Korea-Japan Future Dialogue

![[ADRN Working Paper] Democratic Backsliding in South Korea](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250702151055558995988(0).jpg)

Working Paper

[ADRN Working Paper] Democratic Backsliding in South Korea

Asia Democracy Research Network | 2025-03-12

![[ADRN Working Paper] The Impact of the Millennials and Gen Z on Democracy in Northeast Asia](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/202505231731371005535793(0).jpg)

Working Paper

[ADRN Working Paper] The Impact of the Millennials and Gen Z on Democracy in Northeast Asia

Asia Democracy Research Network | 2025-03-12