Japan is experiencing a major political fund scandal. It is aligned that the Abe and Nikai factions within the governing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) failed to report a significant portion of income from political fundraising parties. The total amount is estimated to be approximately 800 million yen (approximately USD 5.5 million) over the five-year period from 2018 to 2022. As of January 2024, a lower house member Yoshitaka Ikeda had been arrested, and the Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office was reported to be considering prosecuting the treasurers of the two factions (NHK 2024-01-13).

While the Abe and Nikai factions together possessed about 140 Diet members prior to the 2024 election, only two have thus far commented on the case in public. It has been reported that the leadership of the factions has asked their members not to speak publicly about the case. This indicates a lack of accountability in Japanese politics.

Given the lack of enthusiasm among individual Diet members to engage with the public on this issue, the government’s approach to political reform seems somewhat tepid and superficial. Former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida took the initiative of establishing a political party reform body within the LDP. However, an investigation revealed that ten of the 38 members of that body were affiliated with the Abe faction (NHK 2024-01-11). Kishida is criticized for his reluctance to implement meaningful reforms.

This scandal demonstrates a weak accountability in Japanese politics. Why did the faction members not raise this issue voluntarily? Why have they been refraining from talking about the case to the public, although they are elected officials who should abide by the law? In sum, what are the reasons for the lack of vertical accountability in governance in Japan? This paper argues that, while freedom of the press and of speech is well protected in the country, weak political participation of citizens, or weak exercise of “positive liberty,” fails to hold politicians, the party, and the government accountable.

1. Governance in Japan

In Japan’s governance, the bureaucracy has historically held significant influence over policy creation and implementation, with citizens expected to adhere to these policies.[1] Although the political landscape changed under the Abe admіnistration, which strengthened the power of the cabinet secretariat over the bureaucracy, the centrality of the bureaucracy’s role returned under the Kishida admіnistrations. The legislature’s lack of sufficient expertise and knowledgeable personnel has contributed to the bureaucracy’s continued dominance. Each Diet member in Japan possesses only two to three staff, whereas each American congress member has about 40. In addition, by conducting its politics of influence peddling until the mid-1990s, the LDP had established patron-client relations between politicians and citizens (Kobayashi 1997, Chapter 7; Kono and Iwasaki 2004).

From the perspective of society, Japanese tend to refrain from challenging the state on matters that they perceive as patronizing. Instead, they demonstrate a reluctance to engage in political participation, relying on the government to address collective action problems in the public sphere. Because of such an attitude towards political participation, the number of people with a political party affiliation is relatively low. The International Social Survey Program study of Citizenship conducted in 2004 revealed that only less than 5% of respondents specified their political party affiliation “when asked which party” they typically support. This is a clear contrast to the United States, where over 40% of respondents specified their political party affiliation in the same research. Although the United States shows an exceptionally high percentage of individuals with political affiliation compared to other countries, North European and other Anglo-Saxon countries also had about or more than 10% of respondents specifying their party affiliations (Gibson et al. 2004, “Party Affiliation”). In comparison to other developed democracies, the lack of interest in political participation is distinctive in the case of Japanese citizens.

Rather than engaging in political processes and contributing to the resolution of collective action problems, Japanese citizens tend to expect and depend on the state. Compared to their interest in policy outputs, their interest in inputs is substantially weaker (Murayama 2003; Neary 2003). The Japanese population demonstrated a lack of interest in political participation in post-World War II period. The general population has historically demonstrated a lack of motivation to influence political processes. Instead, they have tended to rely on the government as a “charitable parent” who provides protection to its citizens, as articulated by Japanese philosopher and political activist Osamu Kuno (Kuno 1970; Yatsuhiro 1980, 6, 45-46). In light of these observations, the state-society relations literature of comparative politics and the domestic politics literature of international relations have consistently categorized Japan as a strong state, a statist country, or an elitist democracy (e.g., Katzenstein 1978; Katzenstein 1985; Risse-Kappen 1991).

2. Inactive Civil Society and Low Civil Liberty

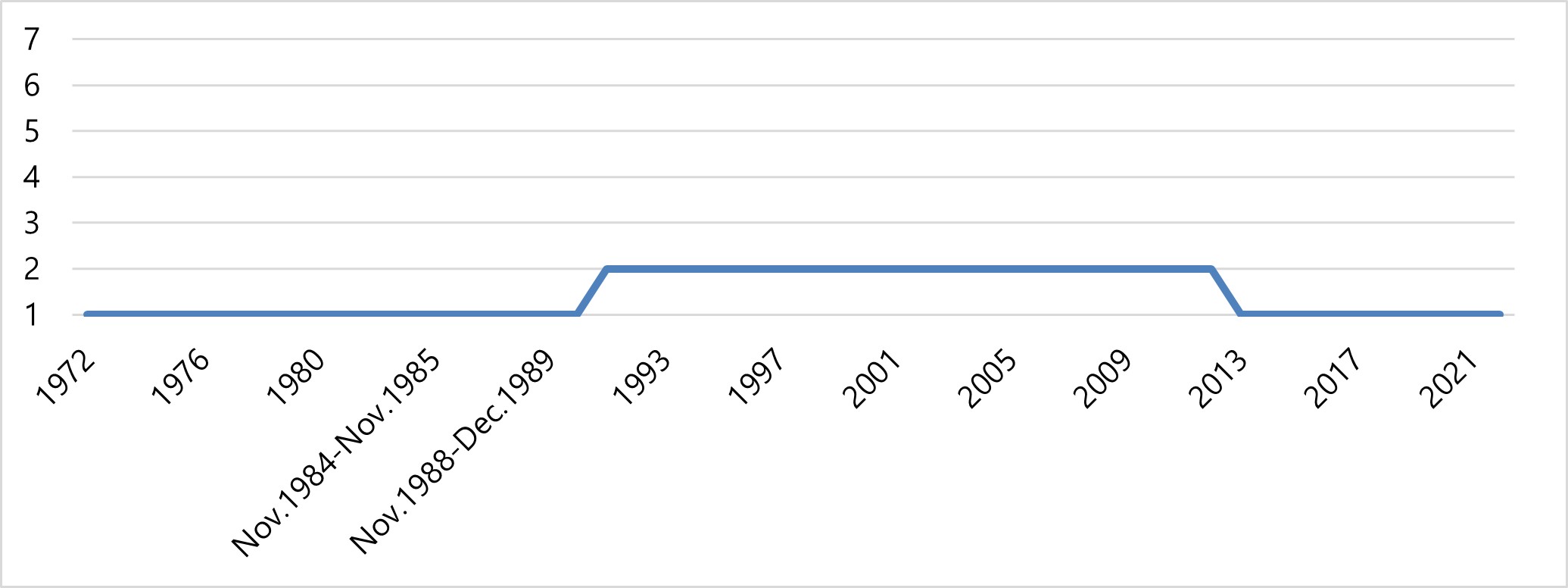

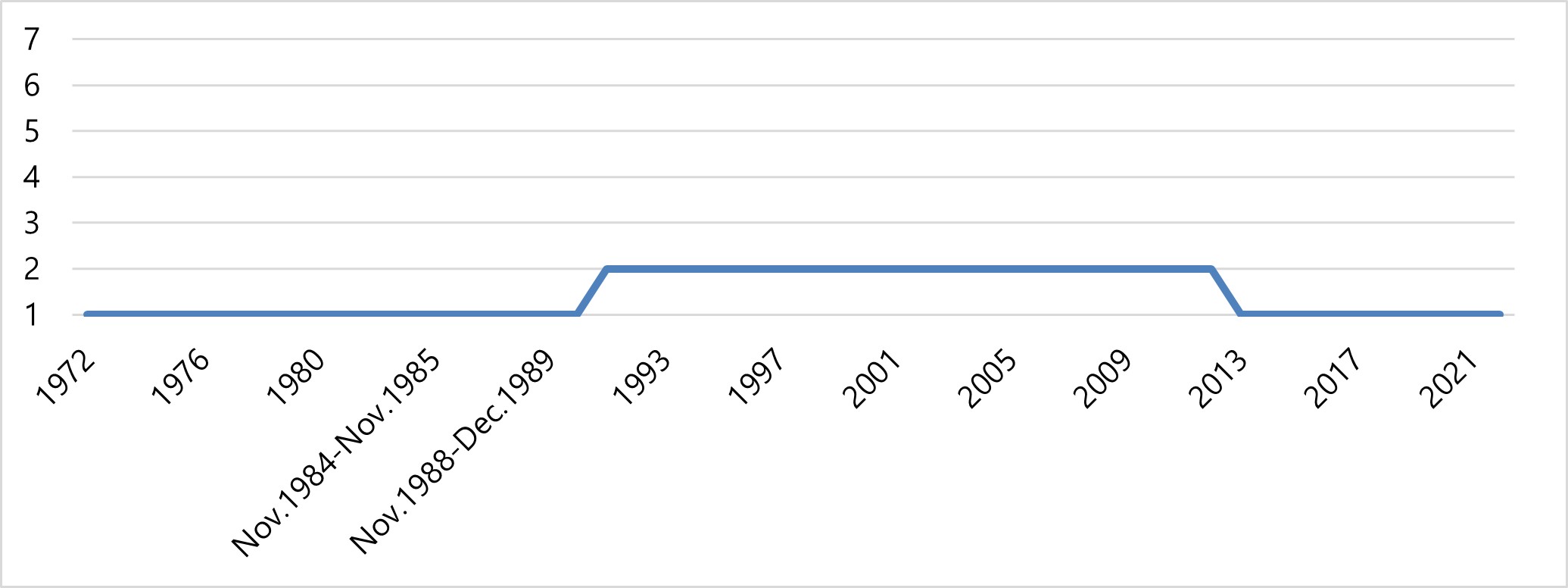

Robert Dahl argues that two dimensions are necessary for a country to be a democracy, or “polyarchy” in his term: public contestation and participation (Dahl 1971). There has been a notable level of public contestation in Japan since the conclusion of the World War II. Despite the LDP’s nearly 40-year tenure between 1955 and 1993, the context was one of freedom of elections. Although the party conducted a politics of influence peddling during its years in office, citizens exercised their freedom to criticize the government, holding demonstrations and contesting in elections. Since Freedom House started collecting data on political rights and civil liberties in 1972, Japan has consistently scored either 1 or 2 out of 7 (with 1 being best and 7 being worst) on civil liberties (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Japan’s Civil Liberty Scores, 1972–2022

Source: Freedom House n.d.

While Dahl measures political participation based on suffrage, citizens’ political participation can also be measured by the existence of a vibrant civil society from the viewpoint of the civil society literature (Tocqueville 1969; Coleman 1988; Putnam, Leonardi and Nanetti 1993). Participatory democracy is a systеm in which civic associations play an active role in addressing collective action problems in the public sphere. It regards citizens not only as subjects to be governed, but also as governors, influenced by communitarianism, where the common good is considered ‘the behavioral principle of the people’.

However, citizens are not necessarily active in participating in politics and solving collective action problems in all democracies. Italy serves as an illustrated example. Scholars such as Edward Banfield and Robert Putnam have posited that a political culture of vertical personal relations can impede the flourishing of civil society (Banfield 1958; Putnam, Leonardi and Nanetti 1993). This seems to apply to the case of Japan as well.

The type of liberty exercised by the Japanese seems to affect state-society relations. In order to satisfy the two requisites of democracy which were defined by Dahl, different types of liberty are necessary. For the exercise of public contestation, the concept of negative liberty, as defined by Isaiah Berlin, is essential. Negative liberty can be defined as the absence of limitations or interference from others. Public contestation may occur at various scales, from boycotts and strikes to demonstrations. Such actions are feasible when the guarantee of liberty from external influence is in place. On the other hand, in addition to negative liberty, positive liberty is a prerequisite for political participation. This is the liberty to engage with others, form agreements with them, and let oneself and others obey certain limitations, which cannot be attained through the mere exercise of negative liberty (Berlin 1958).

The Japanese people tend to only exercise public contestation or negative liberty, but they often lack the will to participate in political activities, which would constitute positive liberty. What factors have contributed to this phenomenon? An insight into this phenomenon can be gained from an examination of the Japanese understanding of the concept of the public (see, for example, Sasaki and Kim 2002; Yamakawa 1999).

3. Concept of the Public in Japan

As Jürgen Habermas observed, the concept of the public has undergone a transformation within Western culture. In feudal societies during the medieval period, the concept was used to express high social status or power. With the advent of the modern state, the public concept came to be used as a synonym for the state, as states expanded their admіnistrative functions. However, as citizens’ economic activities became increasingly distinct from those of the state, the public concept came to encompass the citizenry (Habermas 1991). Additionally, Hannah Arendt defines the modern public sphere as relations among citizens (Arendt 1973).

In contrast, the concept of the public in Japan has remained largely unchanged over time. As was understood in the feudal systеm, the term “public” continues to be used to refer to those at the pinnacle of the social hierarchy in Japan. From the introduction of the public concept in Japan until the present, the term has been used to refer to a variety of figures, including lords, emperors, dominators, heroes, warlords, and bureaucrats, depending on the assumed hierarchy. In contrast, the term “private” has historically been used to refer to subjects and common people (Kim 2002, i). While the term “public” is subject to interpretation depending on the assumed hierarchy, the very concept of the public itself has remained consistent. Yoshiko Terao explains the genesis and etymological origins of the public concept in Japan as follows:

The Japanese word “oyake [(public or 公)]” originally meant “great house,” which obtained the reading when the words “公” and “私 [(private or I)]” were brought from China. Then “公” and “私” rooted representing structural relations which function to support the feudal systеm during the Edo period. In the Edo’s feudal systеm, the shogunate was the “公” and feudal clans were “私,” while feudal clans were the “公” and vassals were “私” in their relations. Such systеm was embedded into the very bottom of the feudal systеm as can be seen in the word “奉公” [which means “apprenticeship” but writes as “contribution to the public”]. When comparing this structure to the public/private relationships of the West, Western public/private basically do not have hierarchical relations but were considered to constitute different spheres, while “公” was always positioned higher in the relations between “公” and “私,” and was considered to have higher values. The public, as the main players in the public sphere of Europe and America, is a group of individuals who is in charge of the public and are rational. They are the group of citizens who can be rational in their dialogues with rational others in the public sphere. “私” as first-person pronoun was established in the latter half of the medieval period, and differing from “我 (I),” “私” as a humble term taking a back seat to the others as a “公” cannot be an existence to have momentum to claim and justify its existence and thinking (Terao 1997, 135. Square brackets were added by the author).

Due to this understanding of the public as those at the apex of the hierarchy, the actors engaged in governance within the public sphere are perceived as exclusively state actors. As Terao points out, while the “general public” in English tends to have the connotation of sovereign members, “koshu (公衆)” as its Japanese translation does not have such a connotation, but it simply denotes people (Terao 1997, 136). As a result of this understanding of the public concept, Japanese citizens have typically refrained from engaging in political participation, asserting their rights only when these are contested. As posited by Hiroshi Minami, a Japanese psychologist, “selfhood is asserted in Japan usually only from the viewpoint of selfish individual benefits, not from the viewpoint of autonomous individual dignity being free from the interference of authority” (Minami 1953, 40). In other words, citizens are regarded as voicing their opinions not to fulfill their civic duty of participating in public governance, but rather as people who are not responsible for it.

Japanese citizens tend to have little interest in making inputs in politics and public policy (Murayama 2003). This makes a contrast when compared to citizens of other Western countries in providing input through avenues such as advocacy and lobbying. The number of NGOs with an advocacy function is relatively limited in Japan, as Robert Pekkanen points out (Pekkanen 2006). A survey conducted by the Johns Hopkins University group revealed a notable discrepancy in the ratio of service-providing NGOs to advocacy NGOs between Sweden and Japan. While the ration in Sweden was 1 to 1.07, in the early 1990s, it was significantly lower in Japan, at approximately 1 to 0.14.[2] The Japanese in general are not interested in the exercise of positive liberty or participation in politics. Japanese citizens rely on the authority for governance and tend not to take individual actions or participate politically (Kawashima 2000). Problems within the public sphere have historically been perceived as matters to be addressed by state actors.

4. Lights for Change

While this political culture remains dominant in Japan, there have been multiple indications of a shift in attitudes. First, the Internet has become the dominant platform for citizens to raise ’their voices and launch petition campaigns virtually, even for those who are not willing to engage in street protests. Social networking sites are also utilized as a means of expressing one’s views.

Members of younger generations are becoming increasingly active in a variety of social and political activities, including speaking out, conducting fundraising campaigns, engaging in advocacy, and so forth. One such indication was observed in the case of the coup in Myanmar in February 2021. Young activists, journalists, and filmmakers remain committed to spreading information about Myanmar, fostering awareness, and advocating for a change in Japan’s policy towards the country.

Can we thus hope to conclude that society is undergoing a transformation? Possibly, but some substantial research would be necessary before making such an assertion. ■

References

Arendt, Hannah. 1973. The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Banfield, Edward C. 1958. The Moral Basis of a Backward Society. New York: Free Press.

Berlin, Isaiah. 1958. Two Concepts of Liberty: An Inaugural Lecture Delivered before the University of Oxford on 31 October 1958. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Coleman, James S. 1988. “Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital.” The American Journal of Sociology 94: S95-S120.

Dahl, Robert A. 1971. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Freedom House. n.d. “Freedom in the World: Country and Territory Ratings and Statuses, 1973-2023.” https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world (accessed November 18, 2023).

Gibson, Rachel, Shaun Wilson, and Markus Hadler. 2004. “International Social Survey Programme 2004: Citizenship.” Cologne: GESIS Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.11372 (accessed January 15, 2024)

Habermas, Jürgen. 1991. (translated by Thomas Burger, with the assistance of Frederick Lawrence), The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Hyden, Goran. 1999. “Governance and the Reconstitution of Political Order.” In State, Conflict, and Democracy in Africa, by Richard Joseph. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Johnson, Chalmers. 1982. MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Katzenstein, Peter J. 1985. Small States in World Markets: Industrial Policy in Europe. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Katzenstein, Peter J., and ed. 1978. Between Power and Plenty: Foreign Economic Policies of Advanced Industrial States. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Kawashima, Takeyoshi. 2000. Nihon Shakai no Kazokuteki Kosei (Family-like Structure of the Japanese Society). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Kim, Tae-Chang. 2002. “Hajimeni: Ima naze nihon ni okeru “ooyake” to “watakushi” nanoka (Introduction: The Importance of “Public” and “Private” in Japan Now).” In Kokyo tetsugaku 3: Nihon ni okeru ooyake to watakushi (Public Philosophy 3: Public and Private in Japan), by Tsuyoshi Sasaki, Tae-Chang Kim and eds. Tokyo: Tokyo daigaku shuppankai.

Kjaer, Anne Mette. 2004. Governance. Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: Polity.

Kobayashi, Yoshiaki. 1997. Gendai nihon no seiji katei (Political Process in the Current Japan). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Kono, Takeshi, and Masahiro Iwasaki. 2004. Rieki yudo seiji: Kokusai hikaku to mekanizumu (Politics of Patronage: International Comparisons and Mechanisms). Tokyo: Ashi Shobo.

Kuno, Osamu. 1970. “Niju yonenme wo mukaeru kenpo (Constitution Reaching Its 24th Years).” Mainichi Shimbun, May 1 and 2.

Minami, Hiroshi. 1953. Nihonjin no shinri (Psychology of the Japanese). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Murayama, Hiroshi. 2003. Nihon no minshusei no bunkateki tokucho (Cultural Characteristics of Japanese Democracy). Kyoto: Koyo Shobo, 2003.

Neary, Ian. 2003. “State and Civil Society in Japan.” Asian Affairs 34, 1 : 27-32.

NHK. 2024a. “Jimin “seiji sasshin honbu” de hatsukaigo: Kishida shusho ga tokaikaku ni ketsui (LDP’s “Political Reform Headquarters” Holds First Meeting; Prime Minister Kishida Determined to Reform Party).” NHK, January 11.

______. 2024b. “Seiji shikin jiken: Abe ha to nikai ha no kaikei sekininsha wo zaitaku kiso de kento (Political Fund Case: Treasurers of Abe’s and Nikkai’s factions to be considered for home prosecution).” NHK, January 13.

Pekkanen, Robert. 2006. Japan’s Dual Civil Society: Members Without Advocates. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Putnam, Robert D., Robert Leonardi, and Raffaella Y. Nanetti. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Risse-Kappen, Thomas. 1991. “Public Opinion, Domestic Structure, and Foreign Policy in Liberal Democracies.” World Politics 43 (July 1991): 479-512.

Sasaki, Tsuyoshi, Tae-Chang Kim, and eds. 2002. Kokyo tetsugaku 3: Nihon ni okeru ooyake to watakushi (Public Philosophy 3: Public and Private in Japan). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Terao, Yoshiko. 1997. “Toshi kiban seibi ni miru wagakuni no kindaiho no genkai (Limitations of Japan’s Modern Laws concerning Urban Infrastructure Improvement).” In Gendai no Ho 9: Toshi to Ho (Modern Law 9: Cities and Law), by Masahiko Iwamura, et al and eds. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. 1969. (George Lawrence trans., J.P. Mayer ed.), Democracy in America. New York: Perennial Classics.

Yamakawa, Katsumi. 1999. “Kokyosei no gainen ni tsuite (On the Concept of the Public).” Keynote lecture at the Annual Meeting of Nihon Kokyo Seisaku Gakkai (Public Policy Studies Association Japan).

Yatsuhiro, Nakagawa. 1980. Obei demokurashi heno chosen: Nihon seiji bunka ron (Challenge to Western Democracy: Japanese Political Culture). Tokyo: Hara Shobo.

[1] On the central role bureaucracy plays in Japan, see, for example, Johnson 1982.

[2] The number for Sweden is as of 1992, and that for Japan is as of 1995. The Johns Hopkins University, Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project.

■ Maiko Ichihara is a Professor in the Graduate School of Law and the School of International and Public Policy, and Assistant Vice President for International Affairs at Hitotsubashi University, Japan.

■ Edited by Hansu Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | hspark@eai.or.kr

![[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability in Japan’s Governance: Impact of Public Conception (Interim Report)](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250403183914822722199.jpg)

![[ADRN Working Paper] Democratic Backsliding in South Korea](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250702151055558995988(0).jpg)

![[ADRN Working Paper] The Impact of the Millennials and Gen Z on Democracy in Northeast Asia](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/202505231731371005535793(0).jpg)