![[ADRN Issue Briefing] State of Democracy in Asia and the Pacific: The End of the Decline?](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20231227174229369387958.jpg)

[ADRN Issue Briefing] State of Democracy in Asia and the Pacific: The End of the Decline?

Commentary·Issue Briefing | 2023-12-27

Michael Runey

Adviser in the Democracy Assessment, International IDEA

Michael Runey, an Adviser in the Democracy Assessment team of Global Programmes at International IDEA, discusses the trends of democracy in Asia and the Pacific highlighted in the Global State of Democracy (GSoD) 2023 Report. The author notes that despite a recent pause in democratic declines, most Asian countries still lag behind the global average. Given the fragile state of press freedom and the effectiveness of parliament and civil societies in these regions, the author emphasizes the need to bolster support for independent media and strengthen countervailing institutions to ensure checks and balances.

※ This Issue Briefing is the summary of the Asia and the Pacific region in the Global State of Democracy 2023 by the International IDEA (https://www.idea.int/gsod/2023/).

International IDEA’s annual Global State of Democracy report shows that across every region of the world, democracy has continued to contract, with declines in at least one indicator of democratic performance in half of all countries assessed in the report. But after five consecutive years of more countries experiencing declines in their democratic quality than improvements, the data shows that this trend may have, in Asia and the Pacific, largely paused after five years of steady declines in most indicators.

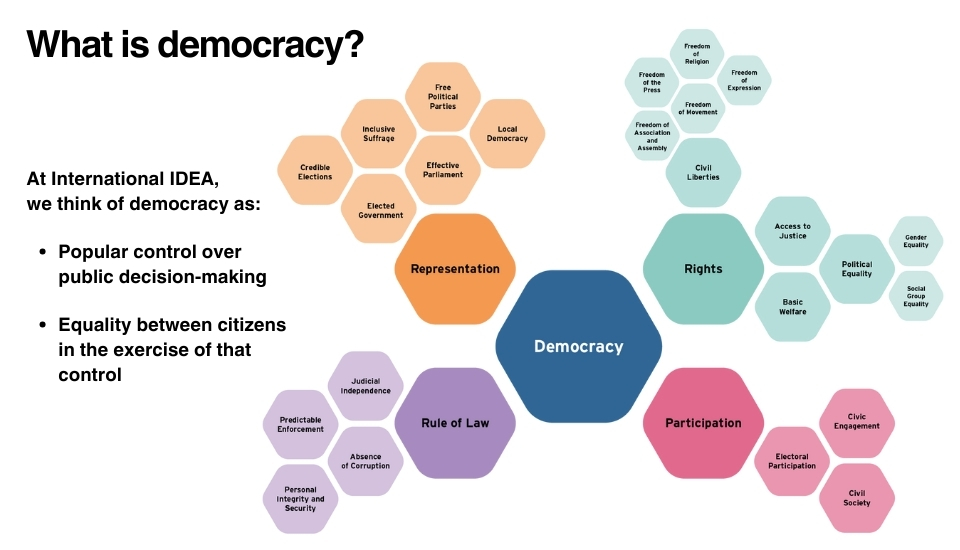

These findings are based on the Global State of Democracy Indices (GSoD Indices), International IDEA’s quantitative dataset of democratic performance launched in 2015 and containing data from 1975 to the present. The indices measure democratic trends at the national, regional and global levels across a broad range of different categories of democracy and include data for 174 countries across the globe, 35 of which are in Asia and the Pacific. In lieu of a single democracy score, the GSoD Indices measure four main categories of democracy – Representation, Rights, Rule of Law, and Participation - which are based on 157 individual indicators from 20 diverse sources: expert surveys, standards-based coding by research groups and analysts, observational data and composite measures. Each of these four measures is comprised of several of the 17 factors, as seen in Figure 1 below.

This data show that in every region of the world, democracy has continued to contract, with declines in at least one indicator of democratic performance in half of the countries covered by the GSoD Indices. But it is in Asia and the Pacific where the trend is most ambiguous and least severe. When we look at five and one year statistically significant trends in the data for the region what we see in 2022 is not continued decline but mostly scores plateauing after years of declines.

Whether or not this is “good” news for a given country largely depends on where it stood before the widespread declines of recent years began. At one extreme, we see countries with firmly established democratic institutions like Australia, Japan and South Korea continuing to perform well across the GSoD Indices while at the other authoritarian regimes in Laos, China, North Korea and Turkmenistan occupy the lower rungs of the global rankings in each of the GSoD’s four core measures of democracy. The vast majority of the diverse Asia and the Pacific region lies somewhere between these two poles. To reflect the diversity of Asian democracies, this text will work through the major trends at the country-level according to the GSoD Indices four main categories of democracy, and then close with short reflections on two broader trends and accompanying courses of action to ensure the region’s future remains democratic.

Figure 1. The Global State of Democracy conceptual framework

Representation

The GSoD’s first core measure of democracy is representation, or the quality of representative government in a country. Malaysia made significant improvements in this measure over the last five years due to improvements in Credible Elections and Free Political Parties, which can be credited in part to the convincing defeat of the long-powerful United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) in November 2022 elections, which had clung to power in the face of persistent and wide-ranging corruption allegations (Bersih 2022; Lee 2022; Wee 2022). The Maldives was the other country to make major improvements in Representation due to gains in the measures of Effective Parliament, Credible Elections, Elected Government and Free Political Parties.

Two countries scheduled to have general elections in early 2024, however, saw five-year significant declines. India’s decline in Representation was tied to reports that the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party benefited from unequal treatment by Facebook and used hate speech during campaigns in the 2019 general election (Purnell and Horwitz 2020; Safi 2019; Tiwary 2022; Chakrabarty 2023). Bangladesh saw a significant decline in Elected Government over a failure to improve since the much-criticized 2018 general elections (The Wire August/10/2018; Siddiqui and Paul 2019; HRW 2018). Arrests of opposition figures there began as early as 2022, and a steady escalation of protests, violence, and polarization has also been documented in International IDEA’s monthly-updated qualitative dataset, the Democracy Tracker (International IDEA 2023; Hasnat and Mashal 2022).

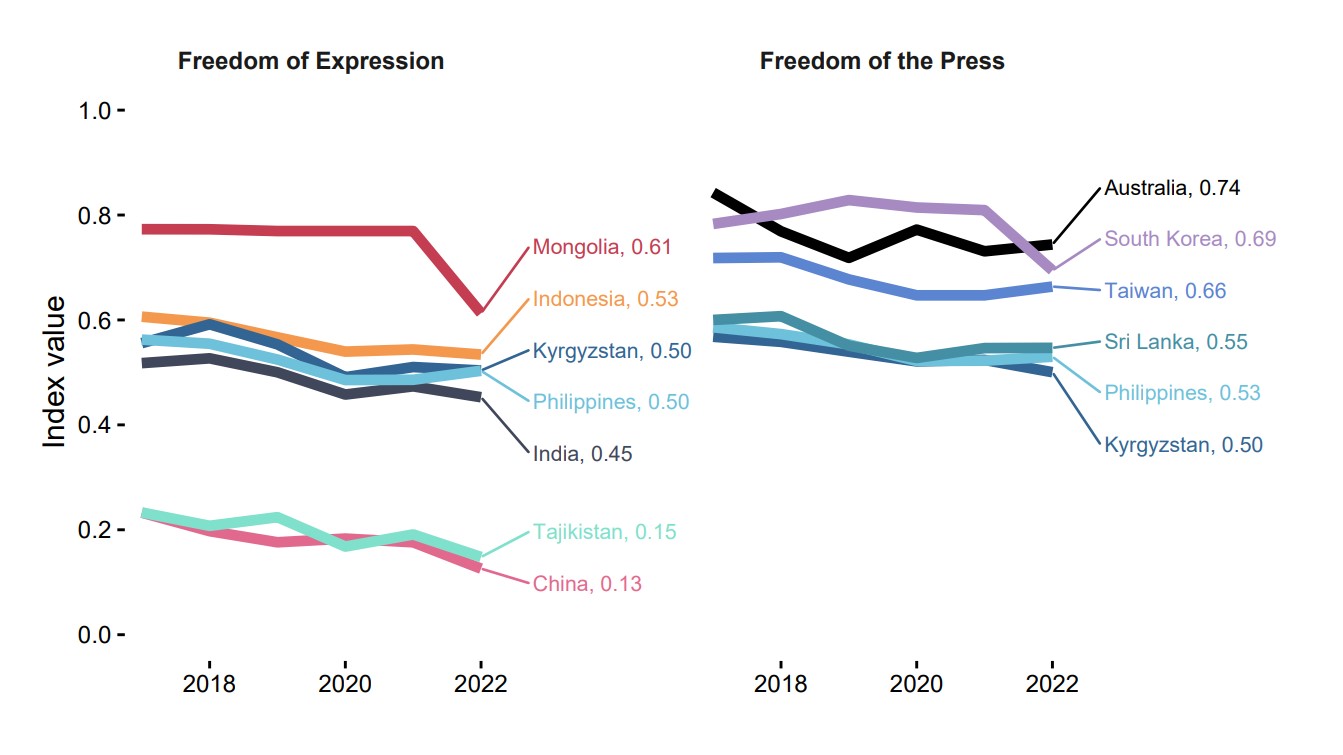

Rights

The respect for human rights, and especially the civil and political rights measured under Civil Liberties in the GSoD dataset, continues to be an area of concern and decline across Asia and the Pacific that runs contrary to the broader trend of stability. India, Maldives, the Philippines and Sri Lanka are all mid-performing countries that saw significant declines over the last five years. The regional average for Civil Liberties continues to be well below the world’s, and most people in Asia and the Pacific live in a country that has seen a significant decline in this score in the last five years. Examples of what this looks like on the ground abound. Amnesty International was forced to close its doors in India in 2020. Sri Lanka responded to hundreds of days of mass protests that forced the president’s resignation by introducing laws to restrict the freedoms of association and assembly (Amnesty International n.d.) (HRW 2022). Declines in Freedom of the Press and Freedom of Expression are also occurring across the region and affecting even high performing democracies like Australia, as seen in the figure below:

Figure 2. Variations in Freedom of Expression and Freedom of the Press for Selected Countries 2017–2022

These declines take place during a time of historic changes in how media is consumed and shared across Asia and the Pacific, where internet penetration rose from 48 to 64 percent between 2017 and 2022. This growth has not been universally enjoyed and has, depending on local political contexts, amplified, reduced, or simply altered pre-existing social inequalities. (ITU 2023; Setiawan, Pape and Beschorner 2022). The introduction and broad uptake of new digital technologies and forms of media are proving to be neither an inherently democratic or autocratic force, but a space for political contestation between domestic and foreign forces (Sinpeng 2020; Farrell 2022).

Rule of Law

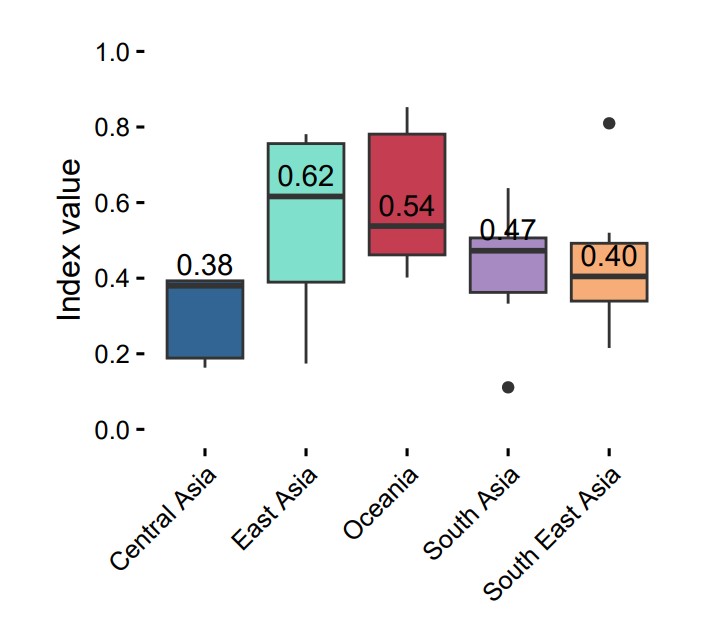

This year’s Global State of Democracy report included for the first time a score specifically dedicated to the Rule of Law. As visible in the graphic below, these scores vary widely between subregions, with Oceania and East Asia performing strongly and Central Asia the lowest. Across the region, it has fallen to institutions like anti-corruption bureaus and the judiciary to push back against executive overreach in the region as weak parliaments have proven incapable of providing a first round of defence.

Figure 3. Distribution of Rule of Law scores by subregion 2022 (median scores for subregions annotated)

One of the key issues of contention in courts has been LGBTQIA+ and women’s rights. A Hong Kong court removed the requirement of sex-reassignment surgery prior to legal gender recognition, a South Korean court recognizing the rights of same-sex couples to social benefits, and an Indian court legalized abortion regardless of marital status (Lau 2023; Pandey 2022; Yoon 2023). The judiciary has also been one of the few countervailing institutions pushing back against the decline in Freedom of Expression and Freedom of the Press. In an otherwise tumultuous year in Pakistan, a colonial-era law criminalizing criticism of the government was struck down by a Lahore court (Al Jazeera March/30/2023). A Filipino tax court also cleared Nobel laureate Maria Ressa of multiple politically-motivated tax evasion charges – a decision hailed globally as a win for press freedom and the rule of law (OHCHR 2023a).

Participation

Participation, or the measure of mass participation in democracy through elections and organization, is a strong point for most of the region, with most countries scoring at mid-range or high-performing levels. The sole exception is Central Asia, which is also the lowest-performing subregion globally, reflecting how entrenched its autocratic elite are and the dearth of countervailing institutions to check their authority.

More broadly across Asia and the Pacific, it is mass public participation – above all, in elections – that have acted as the most powerful countervailing force against autocracy and entrenched elites in the region in recent years. This was visible in Malaysia in 2022 when lowering the voting age to 18 from 21 and introducing automatic voter registration led to three million more voters participating than in the previous 2018 election and firmly removed the corruption-tainted UMNO from power (Fernandez Gibaja 2022; International IDEA n.d.). The expanded electorate worked in concert with the nation’s anti-corruption commission, which obtained a conviction of former prime minister and UMNO president Najib Razak for corruption for his role in the country’s 1MDB scandal (Latiff 2023).

However, significant public mobilization is not always a guarantor of democratic progress. The 2014 coup d’état in Thailand has been met by growing youth engagement, varied forms of activism and civic engagement. Like Malaysia’s, the May 2023 election in Thailand also saw the highest voter turnout in the country’s history, which contributed to the historic first-place finish of the progressive Move Forward Party at the expense of more established parties (International IDEA 2023). Unlike Malaysia, the country’s political establishment prevailed when the military-appointed Senate blocked Move Forward’s efforts to assemble a ruling coalition. In August 2023, a Pheu Thai-led coalition viewed by the military as more amenable successfully built a governing coalition without Move Forward (Nikkei Asia August/15/2023).

Where do we go from here?

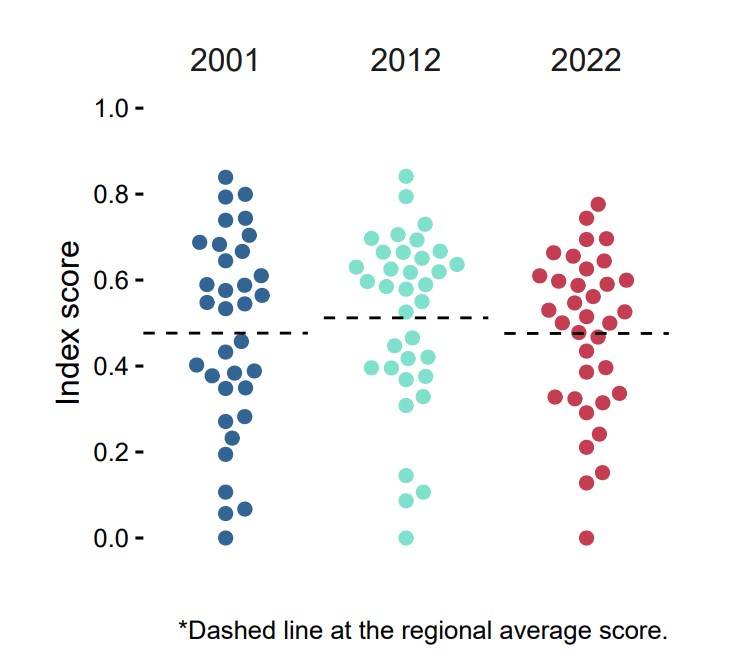

What can be done to stem declines and reverse the democratic declines of the last five years? One area that activists, democracy assistance providers, and donors should focus on is scaling up technical and financial assistance to independent media and advocating for robust legal protections for journalists. A free press is a core component of any democracy, but in 2022 and 2023, governments in Bangladesh and Kyrgyzstan instituted bans on popular media outlets, a Pakistani court strengthened the country’s blasphemy laws, and the South Korean government took action against a major media outlet and cut funding for public broadcasting in retaliation for perceived unfavourable coverage (Imanaliyeva 2023; Masood 2023; OHCHR 2023b; Daily Star February/21/2023) (CIVICUS 2022; RSF 2022). This is a long-term trend – as of 2022, Freedom of the Press had regressed to 2001 levels, far down from the region’s historical peak in 2012, as seen in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4. Freedom of the Press improved from 2001 to 2012, but had returned to 2001 levels in 2022 (each dot represents a country)

A second area of focus should be the slow work of establishing complementary countervailing institutions – those social institutions that, inside and outside of government, that balance the distribution of power and ensure popular control over decision-making. The contrast between Thailand and Malaysia in the Participation section above is a key example of the risks in relying on a sole countervailing institution – in Thailand’s case, elections – instead of an array that provide each other with mutually reinforcing support.

This is not to say the relevant complementary institution of the anti-corruption commission in Malaysia’s case was a cure-all. The once-powerful Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi), working together with capable civil society organizations and a largely free press, was famously able to secure hundreds of high level convictions in the first two decades of the twenty-first century (Buehler 2019; Umam et al. 2020). But it has since been subjected to an elite backlash and seen its independence curtailed (Mulholland and Sanit 2020). Its rise and fall show that anti-corruption commissions can be a core part of a set of high-performing and complementary countervailing institutions – such as well-managed and open elections and a free media – but they cannot be a shortcut to sustainable democracy.

Conclusion

Despite the overall pause in democratic decline in 2022, most countries in Asia and the Pacific are below the global average in key measures of democracy such as Rule of Law and Representation. The growth of restrictions on freedom of speech, censorship of the media, and legal action against investigative media remain a concern across the broad and diverse region. While technocratic and legalistic institutions like the judiciary and anti-corruption commissions have been able to stem to some extent the declines of recent years, they remain institutions that are dependent on political will and are doomed to inefficacy without true independence. Collective efforts will be required across the region to revitalize the core instruments of democracy, such as parliaments, to prevent further democratic decline. ■

References

Al Jazeera. 2023. “Pakistani court strikes down sedition law in win for free speech.” March 30. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/30/pakistani-court-strikes-down-sedition-law-in-win-for-free-speech

Amnesty International n.d. “Protect Our Human Rights Work in India.” https://www.amnesty.org/en/petition/protect-our-human-rights-work-in-india/

Bersih. 2022. “Preliminary Report of the 15th General Election.” December 6. https://bersih.org/2022/12/06/preliminary-report-of-the-15th-general-election/

Buehler, M. 2019. “Indonesia takes a wrong turn in crusade against corruption.” Financial Times. October 2. https://www.ft.com/content/048ecc9c-7819-3553-9ec7-546dd19f09ae

Chakrabarty, Sreeparna. 2023. “Bill introduced to remove CJI from panel to select Election Commissioners.” The Hindu. August 10. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/bill-moved-to-remove-cji-from-panel-to-select-election-commissioners/article67180873.ece

CIVICUS. 2022. “Concerns about free expression in South Korea with security law, restrictions on press freedom and anti-north activism.” December 1. https://monitor.civicus.org/explore/concerns-about-free-expression-south-korea-security-law-restrictions-press-freedom-and-anti-north-activism/

Daily Star. 2023. “Dainik Dinkal stops publication.” February 21. https://www.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/news/dainik-dinkal-stops-publication-3253461

Farrell, Maria. 2022. “Your platform is not an ecosystеm.” Crooked Timber. https://crookedtimber.org/2022/12/08/your-platform-is-not-an-ecosystеm/

Fernandez Gibaja, Alberto. 2022. “How young voters are revamping democracy in Malaysia.” International IDEA. November 17. https://www.idea.int/blog/how-young-voters-are-revamping-democracy-malaysia

Hasnat, Saif, and Mujib Mashal. 2022. “Bangladesh Arrests Opposition Leaders as Crackdown Intensifies.” The New York Times. December 9. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/09/world/asia/bangladesh-protests-election.html

Human Rights Watch: HRW. 2018. “Creating Panic: Bangladesh Election Crackdown on Political Opponents and Critics.” December 22. https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/12/22/creating-panic/bangladesh-election-crackdown-political-opponents-and-critics

______. 2022. “Sri Lanka: Revoke Sweeping New Order to Restrict Protest.” September 27. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/09/27/sri-lanka-revoke-sweeping-new-order-restrict-protest

Imanaliyeya, Ayzirek. 2023. “Kyrgyzstan: Court orders closure of RFE/RL’s local affiliate.” Eurasianet. April 27. https://eurasianet.org/kyrgyzstan-court-orders-closure-of-rferls-local-affiliate

International IDEA. 2023. “Democracy Tracker: Bangladesh.” https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/country/bangladesh

______. 2023. “Democracy Tracker: Thailand – May 2023.” https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/report/thailand/may-2023

______. n.d. “Voter Turnout Database: Malaysia.” https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/country?country=135&database_theme=293

International Telecommunication Union: ITU. 2023. “Measuring digital development: Facts and Figures 2023.” https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/facts/default.aspx

Latiff, Rozanna. 2023. “Jailed Malaysian ex-PM Najib loses final bid to review graft conviction.” Reuters. March 31. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/jailed-malaysian-ex-pm-najib-loses-bid-review-graft-conviction-2023-03-31/

Lau, Chris. 2023. “Hong Kong’s landmark transgender ruling: will the rest of Asia now follow suit?” South China Morning Post. February 19. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/lifestyle-culture/article/3210600/hong-kongs-landmark-transgender-ruling-will-rest-asia-now-follow-suit

Lee, Jaehyon. 2022. “Review – The End of UMNO?: Essays on Malaysia’s Dominant Party.” Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia 36. https://kyotoreview.org/book-review/review-the-end-of-umno-essays-on-malaysias-dominant-party/

Masood, Salman. “Pakistan strengthens already harsh laws against blasphemy.” The New York Times. January 21. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/21/world/asia/pakistan-blasphemy-laws.html

Mulholland, Jeremy, and Arbi Sanit. 2020. “The weakening of Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission.” East Asia Forum. January 20. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/01/28/the-weakening-of-indonesias-corruption-eradication-commission/

Nikkei Asia. 2023. “Thailand’s Move Forward ‘will not back’ Pheu Thai’s PM bid.” August 15. https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Thai-election/Thailand-s-Move-Forward-will-not-back-Pheu-Thai-s-PM-bid

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights: OHCHR. 2023a. “UN expert welcomes verdict on Maria Ressa’s tax evasion case.” January 19. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/01/un-expert-welcomes-verdict-maria-ressas-tax-evasion-case

______. 2023b. “Cambodia: UN experts call for reinstatement of Voice of Democracy, say free media critical ahead of elections.” February 20. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/02/cambodia-un-experts-call-reinstatement-voice-democracy-say-free-media

Pandey, Geeta. 2022. “India abortion: Why Supreme Court ruling is a huge step forward.” BBC. October 1. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-63086321

Purnell, Newley, and Jeff Horwitz. 2020. “Facebook’s Hate-Speech Rules Collide With Indian Politics.” The Wall Street Journal. August 14. https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-hate-speech-india-politics-muslim-hindu-modi-zuckerberg-11597423346

Reporters Without Borders: RSF. 2022. “South Korea: RSF concerned by president’s hostile moves against public media.” December 5. https://rsf.org/en/south-korea-rsf-concerned-president-s-hostile-moves-against-public-media

Safi, Michael. 2019. “India: high-profile candidates banned from election trail over hate speech.” The Guardian. April 15. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/apr/15/indian-party-leaders-banned-from-election-trail-over-hate-speech

Setiawan, Imam, Utz Pape, and Natasha Beschorner. 2022. “How to bridge the gap in Indonesia’s inequality in internet access.” World Bank Blogs. May 13. https://blogs.worldbank.org/eastasiapacific/how-bridge-gap-indonesias-inequality-internet-access

Siddiqui, Zeba, and Ruma Paul. 2019. “Some in Bangladesh election observer group said they regretted involvement.” Reuters. January 29. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bangladesh-election-observers-exclusi-idUSKCN1PG0MA/

Sinpeng, Aim. 2020. “Digital media, political authoritarianism, and Internet controls in Southeast Asia.” Media, Culture & Society 42, 1: 25-39.

The Wire. 2018. “Centre Moves New Bill on Appointment of Election Commissioners, CJI Excluded From Panel.” August 10. https://thewire.in/government/new-bill-selection-of-election-commissioners

Tiwary, Deeptiman. 2022. “From 60% in UPA to 95% in NDA: A surge in share of Opposition leaders in CBI net.” The Indian Express. September 21. https://indianexpress.com/article/express-exclusive/from-60-per-cent-in-upa-to-95-per-cent-in-nda-a-surge-in-share-of-opposition-leaders-in-cbi-net-express-investigation-8160912/

Umam, Ahmad Khoirul, Gillian Whitehouse, Brian Head, and Mohammed Adil Khan. 2020. “Addressing Corruption in Post-Soeharto Indoneisa: The Role of the Corruption Eradication Commission.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 50, 1: 125-143.

Wee, Sui-Lee. 2022. “Anwar, Opposition Leader for Decades, Is Now Malaysia’s Prime Minister.” The New York Times. November 24. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/24/world/asia/malaysia-elections-prime-minister.html

Yoon, Lina. 2023. “South Korea Court Recognizes Equal Benefits for Same-Sex Couple.” Human Rights Watch. February 22. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/02/22/south-korea-court-recognizes-equal-benefits-same-sex-couple

■ Michael Runey is an Adviser in the Democracy Assessment team of Global Programmes at International IDEA, where he contributes in research, analysis, communication, and coordination in support of the Global State of Democracy (GSoD) initiative.

■ Typeset by Hansu Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | hspark@eai.or.kr

Center for Democracy Cooperation

Democracy

Asia Democracy Research Network

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20240419123938102197065(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections

Niranjan Sahoo | 2023-12-27

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2024032815145548472837(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?

Ken Godfrey | 2023-12-27