![[Indo-Pacific Strategy Special Report] Executive Summary: Korea’s Global Indo-Pacific Strategy](/data/bbs/eng_special/202212301682812999864.png)

[Indo-Pacific Strategy Special Report] Executive Summary: Korea’s Global Indo-Pacific Strategy

Special Reports | 2022-12-30

Yul Sohn

President of EAI, Professor at Yonsei University

Yul Sohn, President of EAI and professor at Yonsei University, defines Indo-Pacific as the “global region” where multilayered strategies and complex areas overlap, and projects the “symbiosis and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region based on universal norms” as the vision that Korea would pursue. Korea is required to break away from previous diplomatic conceptions confined to the Korean Peninsula and Northeast Asia, and realize a wider scope of value and national interests in the Indo-Pacific region, which has emerged as the core of global economy and security. The author suggests Korea’s role to cope with global challenges and to prevent an armed conflict. For playing the role, it is necessary to persist cooperation with local actors and build complex networks covering economy, technology, environment, and security.

The East Asia Institute (EAI) Indo-Pacific Strategy Research Team [1] presents “Korea’s Global Indo-Pacific Strategy: Building a Regional Order of Symbiosis and Prosperity” as a regional strategy for the Republic of Korea (ROK or Korea). It is an endeavor to redefine Seoul’s role in accordance with Korea’s rising international standing and a shifting world order that stands at a critical inflection point. The report seeks to expand Korea’s influence in the international community by suggesting a regional strategy with a long-term and macrocosmic vision based on temporal and spatial conceptions that are appropriate for Korea’s current status and role.

Ⅰ. World Order Transformation

The world order stands at a critical inflection point. With the U.S.-China strategic competition now having enveloped a variety of issues, ranging from trade to high-tech development to values and norms, mutual mistrust between the two has increased. Moreover, their heightening competition also extends to the realm of military security, raising the possibility of a clash between them, as their respective competing visions for global order vie for dominance. Simultaneously, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has reanimated divisions between the Eastern and Western blocs, whose increasing disassociation threatens the durability of longstanding practices and regulations on international order, including multilateral agreements, abidance with international law, respect for sovereignty, and the peaceful settlement of disputes. As geopolitical competition escalates, the liberal international order’s economic dimension too is in disarray, confronting challenges from the securitization of high-tech competitiveness, the weaponization of economic interdependence, the rearrangement and decoupling of global supply chains, and the formation of regional economic blocks.

Behind this chaotic shift lies a significant transformation in the global economic order. Since the end of the Cold War, neoliberal globalization has flourished, bringing unprecedented levels of wealth to many peoples and societies around the world. However, this process has been accompanied by political populism and economic nationalism, resulting in domestic economic inequalities, social polarization, and a widening in political divisions between citizens. As a result, many nations have gravitated toward inward-looking economic and political avenues in order to better protect and meet their own domestic policy priorities. As a consequence, globalization has witnessed a retreat over the past decade – or deglobalization- that has seen reductions in trade, restrictions on labor mobility, and a turbulent reorganization of global supply chains.

Deglobalization is not a solution to today’s most pressing international challenges. Global health crises, climate change, food insecurity, energy crises, and the subsequent hazards posed by global inflation and economic stagnation in the post-pandemic era, will certainly remain. To address these demanding transnational issues, it is paramount that active, effective, and reliable platforms for international cooperation and global governance remain steadfast. However, with larger countries having increasingly leant on introverted, nationalistic, and self-centered strategies, it is more difficult to respond collectively to these transnational challenges. As an open-trading nation placed on the fault lines of rivalry among powerful nations, Korea is under daunting daunting challenges. To efficiently meet these challenges, Korea should adopt a “whole-of-government” approach with a long-term, macro vision that looks beyond the present administration’s five-year tenure, to the next generation. Through the effort of constructing a new, flexible, and rules-based international order that moves from co-destructive competition to symbiotic coexistence, Seoul must contribute to reversing course of deglobalization and ensuring that rivalry among the great powers does not degenerate into a fully-fledged armed confrontation.

Ⅱ. In Search of a Global Regional Strategy

To address global and wide-reaching difficulties, an astute global governance apparatus must surely be developed. This is unlikely to occur in practice, however. Instead, key players turn to regional mechanisms in order to preparing solutions. In contrast to the past regional strategies that tackled regional issues by coordinating and cooperating with regional players, today’s key players pursue regional strategies in response to global concerns. This view is founded on the conceptualization of the “global region.” [3] By linking the two spaces(global and regional), global regions stress the global context of regional processes. This can be described as a space in which global challenges, tasks, and strategies are projected and multifarious and multi-layered activities are present. Based on this concept, it is understandable why the U.S. desires to protect its global interests through linking its Indo-Pacific strategy with its Euro-Atlantic regional strategy, while China seeks One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative and Asia-Pacific strategies under the banner of the Global Security Initiative (GSI) and Global Development Initiative (GDI).

After identifying common advantages and objectives from a global viewpoint, Korea should construct regional spaces to build its own global regional strategy. Korea is the world’s tenth-largest economy in terms of GDP, the world’s sixth-largest military power in terms of military expenditure, a cultural power house staged at the forefront of global popular culture, and a model nation that achieved industrialization and democratization at the same time. an exceptionally developed country. Korea should play a proactive international role commensurate with its enhanced international status and to do so by readjusting its regional concepts and strategies.

Ⅲ. Why the Indo-Pacific?

The Indo-Pacific region is vital to Korea’s efforts to establish a rules-based international order that can address global issues and protect its own national interests. The Indo-Pacific region is a geographical area that undergoes a significant proportion of global upheavals and transformations, and a strategic region that fosters and promotes Korea’s extended national interests. Until now, Korea’s regional concept has remained largely limited to a narrowly defined geographical area encompassing the Korean Peninsula and Northeast Asia. With the advent of the post-Cold War era, past Korean governments designated Northeast Asia as a strategic region, as made evident by “The Northeast Asian Era of Peace and Prosperity,” “The Northeast Asia Peace Cooperation Initiative,” and “The Northeast Asia Plus Community of Responsibility Initiative.” Consecutive governments have hitherto been unable to move beyond the concept of utilizing regional cooperation other than addressing the North Korean issue. This regional framework was pursued in an attempt to achieve peace on the Korean Peninsula by designating a strategic region that established cooperative relationships with its four surrounding states. However, Korea’s foreign economic opportunities, security linkages and participation in regional organizations have vastly expanded. Seoul should leverage its diplomatic, economic, cultural, and military resources in an expanding regional area in order to serve its national interests and preserve values and principles.

The Indo-Pacific has transformed into a major economic powerhouse of the world over the past decade. This vast geographic region linking the Pacific and Indian Oceans, accounts for 63% of world GDP and 46% of global commerce, and hosts important transport routes that accounts for 50% of global transportation. The regional commerce and supply chains built by Korea, China, Japan, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia now extend to the entirety of Southeast Asia, Australia, India, and South Asia. With an invigoration in goods and capital flows via the Indo-Pacific region, labor mobility is also rising, particularly from India, Bangladesh, the Philippines, and Pakistan, thereby enhancing economic complementarity and promoting the growth and depth of regional and global economic integration. Seoul’s replacement of Northeast Asia with the Indo-Pacific, signifies that Korea’s future regional strategies will look to widening and strengthening its partnerships with India and Southeast Asia, areas projected as the driving force for global economic growth over the next 30 years.

On a security basis, because the Indo-Pacific is home to the world’s most vital maritime transport hub connecting the Indian and Pacific Oceans, major powers competitively advance to the region in order to secure its maritime access. In addition, geopolitical considerations have heightened the strategic significance of the region that bears witness to North Korea’s nuclear and missile provocations, tensions in the Taiwan Strait, territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and competition for civil-military duel use technologies, all threatening the solidity of the liberal international order, that has facilitated the region’s economic prosperity and cross-border political stability since the end of the Cold War. Subsequently, major European Union (EU) countries, as well as the U.S., Japan, India, Australia, and ASEAN are developing their own Indo-Pacific regional policies. Korea is too well positioned to configure and orchestrate its own comprehensive Indo-Pacific security policy, including the installment of economic security measures.

Ⅳ. Key Objectives of Korea’s Global Indo-Pacific Strategy

Adopting an Indo-Pacific strategy does not imply that existing regional conceptions would be replaced in their entirety. On the contrary, major powers across the globe are building regional plans that divide and link numerous conceptual geographical locations using the notion of global region. For example, Southeast Asian nations have already implemented a multilayered regional strategy - ASEAN as a base together with “ASEAN Plus” formula and an Indo-Pacific Outlook. Seoul, therefore, needs to regard the Indo-Pacific region not as a fixed geographical entity in itself but rather a “global region” where preexisting multiple geographical areas overlap. In this light, the Global Indo-Pacific Strategy of the Republic of Korea may be described as a multifaceted spatial strategy, that is comprised of and addresses several functional issues and spatial domains, incorporating long-standing Northeast or East Asian geographic conceptions.

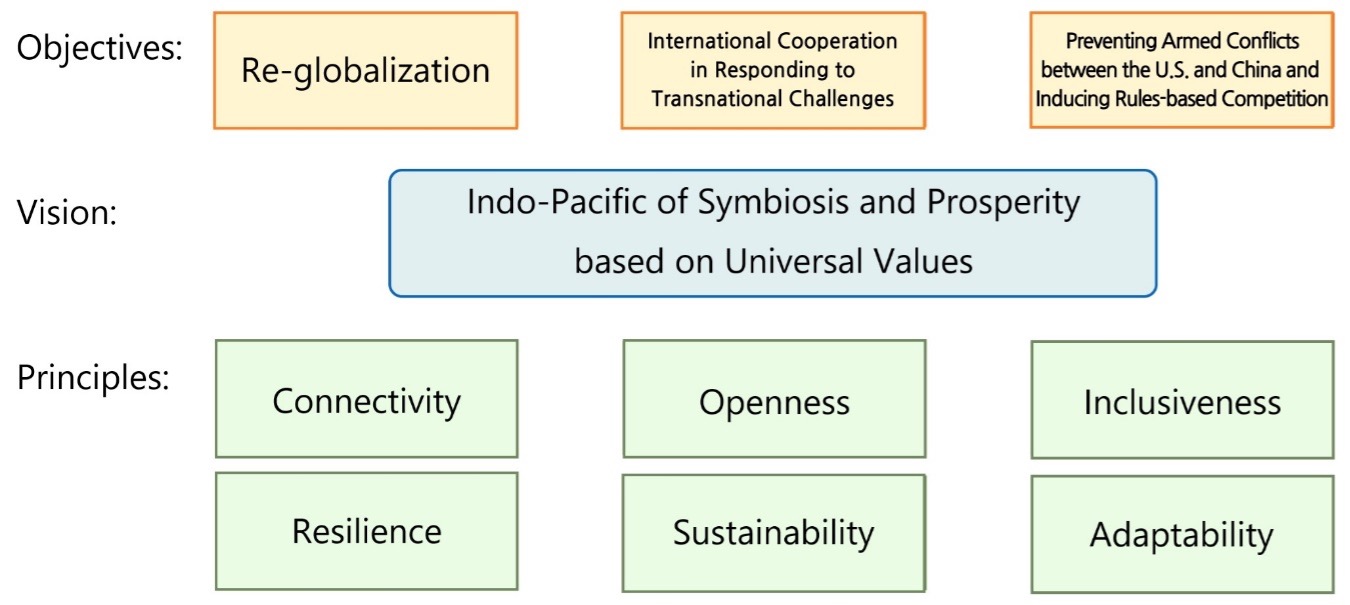

To achieve this, the global Indo-Pacific strategy of Korea must aim for a rules-based Indo-Pacific order by pursuing three essential objectives. The first is to stop deglobalization and promote re-globalization. This pursuit requires reflecting upon the weaknesses in previous forms of globalization so that possible pathways can be identified to produce a form of globalization that is more sustainable and resilient. Attempting to merely rejuvenate earlier formats will be ineffective, as deglobalization captures major economies around the world. While seeking to design a globalization more attune to the demands of the 21st century, it is important to nevertheless be reminded that the core tenets of globalization have been the primary driver of global economic growth over the past four decades, as well as the development of information and communication technology (ICT) and the expansion of global supply chains. Between 1980 and 2020, world trade grew approximately ten-fold, foreign direct investment increased seventeen times, and labor migration tripled. Despite the relative decline in commodities trade and labor mobility over the last decade, capital market integration and digital trade are on the rise, and non-state actors’ global public networks continue to provide politically positive functions. Because the difficulties we confront today are global in scope, a response from the global community as a whole rather than from individual nations is a necessity. The future objective of the Indo-Pacific strategy, therefore, is to establish an area that abides by open and fair rules and norms that advances the beneficial elements of existing formats of globalization and promote re-globalization efforts appropriately; creates an inclusive economic-technology ecosystem at both domestic and international levels; and bolsters the stability and resilience of regional and international supply chains.

The second objective is to encourage international cooperation in addressing and confronting the most decisive transnational challenges of our time. The prevailing threat of climate change, emerging health crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, energy and food insecurity, and terrorist groups possessing weapons of mass destruction (WMD) continue to reveal major limitations in the current world order. No nation can assuredly tackle these pressing challenges alone. State and non-state actors should, therefore, respond collectively through institutional designs and platforms at the global level, although present trends in deglobalization makes such attempts difficult. As such, Korea should strive to actively engage in the implementation of rules and norms that more effectively react to international issues, whilst furthering enduring political stability and concreted, sustainable economic growth, based on the value of symbiosis. Being at a critical fault line of the ongoing U.S.-China strategic competition, Korea should also establish itself as a cohesive, connecting point that can help foster collaboration between the two powers on meeting shared global challenges.

The third objective is to manage the strategic competition between the U.S. and China along pathways that dampen the prospects of violent confrontation involving unimaginable military might occur. This is best achieved by building an encompassing security space in the Indo-Pacific for the two powers to compete in that is based on agreed upon and established rules. The Indo-Pacific region is no stranger to turbulent geopolitical flashpoints, including between the Taiwan Strait, East China Sea, South China Sea, and on the Korean Peninsula. Given these risks, regional states are tasked with establishing a regional security order that better ensures strategic stability before the risk of direct military collision between the U.S. and China escalates dramatically. Washington has sometimes shown a tendency to pursue measures that undermine the legitimacy of its own liberal hegemony, while Beijing’s decision to solidify its authoritarian rule at home and practices a self-centered Wolf Warrior Diplomacy strategy abroad, erodes its potential as a possible and legitimate replacing hegemon. Consequently, if it is impossible for them to reliably lead the future global order on their own, the foreign policies of middle powers in the area, including Korea’s, should work to collaborate in developing a sustainable and inclusive regional security architecture, grounded in principles and rules conducive to regional and international symbiosis.

Ⅴ. Indo-Pacific Regional Operating System: Visions and Principles

Rather than developing and implementing specific policy agendas, the global Indo-Pacific policy of the Republic of Korea should emphasize the construction and reconstruction of the regional order. This report attempts to describe the fundamental values and principles of the Indo-Pacific region, utilizing the concept of operating system in the sense of adhering to the rule of law, regulations, institutions, and norms.

Above all, the Indo-Pacific operating system seeks to promote and sustain a rules-based order. As actors in this region compete and cooperate with one another, it is vital that they are managed within a framework that abides to formal established international laws and treaties authorized by international organizations, like the UN, GATT-WTO, and IMF. It is equally important that the order respects informal norms and practices developed through historical experiences among states, as well as rules developed via ASEAN, etc. To support these broader political initiatives, economic competition, collaboration, and cooperation must too be founded on equitable international standards and norms. Informal and unfair trades and economic coercion through weaponization of economic interdependence must be avoided and should not be tolerated. As such, Seoul rejects any disruptive, unilateral changes to the international system’s status quo via the use of force, instead, looking to strategies that promote multilateral agreements, the peaceful settlement of conflicts based on international law and norms, and freedom of navigation.

The “symbiosis and prosperity in the India-Pacific region based on universal norms” is Korea’s vision for the Indo-Pacific operating system. First, the operating system is founded upon universal and shared liberal values, including human rights, the rule of law, multilateralism, and free trade. Such avenues assure democratic cooperation and more efficient forms of global governance, whose implementation nurtures and protects democratic decision-making procedures by boosting solidarity among nations that share these universal principles. Its practice also supports achieving mutual respect for the international system, the pursuit of national development, and self-determination while respecting the sovereign decisions of each country.

Second, the Indo-Pacific Strategy aspires to achieve a peaceful symbiosis of peoples, communities, and nations within the region. Going beyond the mere parameters of a Machiavellian competition of survival and natural selection, the strategy seeks symbiosis between peoples, nations, their natural environments, and varying principles. It is vital to explore possible pathways in achieving this fundamental, though complex goal, if a durable security order and economic-technology ecosystem can arise to reduce military tensions between the U.S. and China and achieve symbiosis through co-evolution.

Third, the Indo-Pacific operating system aims to assure the co-prosperity for all states in the region. It aims to build a networked platform that promotes mutual prosperity through reciprocal cooperation, that enhances the complementarity of diverse economic systems; ensures the stability and resilience of interdependence; and offers tangible benefits to the members by offering Korean experience and assets. Following this vision, the Indo-Pacific operating system can be operated in accordance with the six principles outlined below.

First, connectivity is the foundational premise of the system. With the help of infrastructure investment and the utilization of multilateral frameworks like RCEP, CPTPP, and IPEF, regional integration can greatly expand. This will also offer further economic, developmental, and political benefits if the connectivity of trade, supply chains, services, digital networks is reinforced. It is also essential to extend security networks, particularly multilateral cooperation networks, in response to terrorism, natural disasters, and other pressing transnational threats.

The second principle is openness. Securing openness is crucial if the Indo-Pacific region is to be developed as a place where competition and collaboration can manageably coexist. The principle of openness provides an more assuring regional environment for states to develop complementary and interdependent relationships, despite areas of severe competition that exists between them. In order to prevent a destabilizing and excessive securitization and blockage of high-tech innovations in important fields, such as semiconductors and batteries, it is necessary to build a technological and economic structure, where openness better enables regional actors to freely cooperate together.

The third principle is inclusiveness. Korea’s Indo-Pacific strategy does not seek to exclude or keep in check any particular state. As long as a state diligently abides by regional and international rules and norms, it is welcomed to join in security cooperation efforts tackling mutually shared threats. While contributing to the development of an inclusive and cooperative Indo-Pacific technological and economic ecosystem, re-globalization efforts must be democratically governed and executed, which would also supplement its connectedness and openness advantages. This would especially be the case for the fair distribution of economic benefits across societies on a domestic level. The penetration of such distribution efforts would not only better afford citizens with the region’s economic prosperity more directly but, in turn, further cement grassroots public support for a rules-based order.

The fourth principle is resilience. The challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, frequent natural disasters, wars, and the ongoing U.S.-China strategic competition reveals the importance for ensuring stability in maintaining the health of domestic economies and the resilience of supply chains. Such a resilience can be achieved through international collaborative efforts channeled towards the development of an early warning system that identifies and prevents a recurrence in supply chain disruptions and better responds to climate change. It is imperative that the Indo-Pacific region, therefore, moves towards instituting resilient re-globalization. This would especially be important for bilateral and multilateral collaboration with island countries across the Indo-Pacific, where infrastructure support and monitoring mechanisms must be built in accordance with such notions of resilience.

The fifth principle is sustainability. This is a key principle in the Indo-Pacific region’s decision-making process, especially on issues concerning population change, resource consumption, economic growth, and responses to climate change and ecological problems. In the context of Indo-Pacific regional development cooperation, Korea needs to prioritize infrastructure investment based on sustainability principles and green ODA.

The sixth principle is adaptability. It is important that the Indo-Pacific operating system is open and enables its participants with the ability to convey their preferences and feel they have an active voice in decision-making process. The openness and inclusion of such voices will benefit the system’s capacity to collectively adapt to emerging challenges and better navigate the issues raised by its participants in a cordial and structured setting. An absence of adaptability would only renegade the operating system as a static and ineffective regional architecture, unable to meet the demands of today’s turbulent world. Since the Indo-Pacific’s order is yet to be determined, Korea’s regional strategy should be centered on pursuing common interests and values that would encourage and garner active participation from regional actors focused on the formation and operation of the emerging order.

Figure 1. Korea’s Indo-Pacific Strategy: Objectives, Vision, and Principles

Ⅵ. Action plan

With establishing multi-layered connections made up of bilateral, minilateral, regional institutions, and non-state actors, Korea should work to identify and implemented crossing and intimately related issues, including trade, investment, finance, high technology, energy, ecology/environment, and a political culture that is invigorated to build a complex and principled network in the Indo-Pacific region. The following suggests the specific action plan for achieving this goal.

1. Active Engagement in the Complex Regional Network Led by the U.S.

In order to ensure the region’s continuing economic growth and political stability that has prevailed since the end of the Cold War, it is crucial that Korea collaborate with the U.S. in establishing a symbiotic and prosperous Indo-Pacific order. Korea should actively participate in the Korea-U.S. cooperation and other minilateral network, such as Quad-plus. An expanded Korea-U.S. alliance that aspires to go beyond the confines of traditional military concerns- including strategic economic and technological partnerships and joint responses to global challenges such as climate change and health security - is the lynchpin of this effort. To support these regional efforts, it is also crucial to strengthen ties with Japan, a vital player in the minilateral network led by the United States, whose combined efforts between Seoul, Washington, and Tokyo would only further cement the sturdiness of the regional order.

2. Continuing and Expanding Strategic Cooperation with China

As the geopolitical and geoeconomic significance of the Indo-Pacific region increases, competition and confrontation between great powers are intensifying. Because of these increasingly dangerous realities, there is a growing fear about the possibility that Korea’s Indo-Pacific policy would be dragged into a possible major conflict in the region. To mitigate these reasonable concerns, Korea should strengthen its bilateral relationship with China with vigilance and prudence. Founded upon an agreed and recognized basis of mutual understanding and respect for differences in their respective political systems, values, and ideologies, Seoul should work with Beijing in establishing a cooperative partnership that, at its center, looks to the future and enhances areas of functional collaboration that better combat common transnational challenges.

3. Strengthening Partnership with ASEAN and India

The Indo-Pacific order’s more expansive geographic inclusion primarily seeks a greater focus on enhancing strategic collaboration with ASEAN and India. Korea should increase its multilateral participation in trade, investment, technology, the environment, and marine security in this part of the region, which is increasing transforming itself into an engine of global economic growth. Based on a recognition of ASEAN centrality, Seoul’s efforts should find areas of common values and vision with India, the world’s largest democracy, when conceptualizing and implementing a regional order together via bilateral and multilateral forums. These relationships and their strengthened collaboration will prove instrumental in meeting regional threats and challenges, including the denuclearization of North Korea and the democratization of Myanmar, while expanding cooperation to include the health, space, cybersecurity, and defense industries.

4. Promoting Multilateral Economic Network for Re-Globalization

Through the expansion and upgrading of current trade agreements such as the RCEP and CPTPP, enhancing their mutual coherence and complementarity, and recovering WTO functions, Korea should play a crucial role in steering the multilateral international economic order toward inclusive globalization, while containing the resurgence of protectionism and unilateralism that has inflicted many major economies. In addition, Seoul needs to seek a resilient form of globalization through multilateral efforts, such as IPEF, to address supply chain instability and prevent an excessive securitization of the economy. For this process, it is vital to develop collaboration with like-minded countries in areas that share Korea’s concerns and goals at the bilateral, minilateral, and regional levels, and to utilize this cooperation to facilitate regional-global linkages.

5. Establishing a Network for Complex Technological Collaboration in Each Sector and Serving as a Bridge Between Developed and Developing Countries

Korea must also contribute to the Indo-Pacific’s development of an inclusive and cooperative technology ecosystem, particularly in an era where the nexus between technology and geopolitics is becoming dominated by a logic of competition, exclusion, and exclusive choice. The strategy’s ecosystem would employ bilateral, minilateral, and multilateral avenues of collaboration in numerous industries, including AI, 5G, cyber, quantum computer, renewable energy, digital trade platform, and biotechnology, acting as a bridge for cooperation for both developed and developing states.

6. Active Contribution in Development Cooperation and Infrastructure Cooperation

Korea is capable of bridging the infrastructure gap in the Indo-Pacific region and contributing to the technological ecosystem’s symbiosis and co-prosperity in the region. Focusing on the digital information and communication industry, Korea’s proven record in such domains positions it well to actively promote development in consolidating ASEAN connectivity, respond to climate change in developing countries, and offer green ODA to fulfill the SDGs. Collaborations with regional communities and inclusive partnership are essential in this regard.

7. Pursuing Environmental Initiatives Considering Ecology-Technology-Economy Links

Korea should help prevent the strategic competition between the U.S. and China from overlooking areas of mutual interest and points of cooperation over the realm of ecology and the environment, a global challenge whose resolution is in the common interest of all humanity. By recognizing and making apparent to others that the addressing of climate problems through multilateral cooperation is also an opportunity for economic and technological innovation, Seoul should promote policies in areas such as renewable energy use, green hydrogen partnership, green shipping network, electric and hydrogen car production development, and carbon market that link climate change response and national interests.

8. Symbiotic Values and Rules-Based Crisis Management and Prevention of Armed Conflict

As the U.S.-China strategic competition appears set to continue as a feature in international politics for the foreseeable future, crises and tensions at critical regional geopolitical focal points, including Taiwan, North Korea, and the South and East China Sea, will intensify. The region’s security and continuing stability rests on its inhabitants’ ability to manage such crises carefully and closely, so that the competition between the two great powers does not lead to armed conflict. It is in Korea’s national interest to steer the U.S. and China towards competing within a rules-based framework underpinned by universal and symbiotic values, notably the prohibition of using force and coercion to change the status quo, a dispute settlement based on multilateral norms, freedom of navigation, and non-proliferation.

9. Promoting a Multi-layered Regional Security Cooperation Network Among Countries Sharing Common Interests

Given that the current U.S.-China strategic competition demonstrates elements of power struggle, Korea must prevent new sources of conflicts arising that threaten to transform the U.S.’ regional hub-and-spokes alliance system into a hierarchical security cooperation system. Seoul needs to identify the interests and threat perceptions of countries in key conflict zones, such as the South China Sea, East China Sea, Taiwan Strait, and on the Korean Peninsula, and promote a multi-layered network with proper division of labor among regional participants that better facilitates the formation of a desirable security order in the region that secures the interests and security of all within.■

[1] The research team consists of the following scholars: Young Ja Bae (Professor at Konkuk University), Chaesung Chun (Chair of EAI’s National Security Research Center and Professor at Seoul National University), Young-Sun HA (Chairman of EAI’s board of trustees and Professor Emeritus of the Seoul National University), Yang Gyu Kim (Principal Researcher at EAI), Dong Ryul Lee (Chair of EAI’s China Research Center and Professor at Dongduk Women’s University), Seungjoo Lee (Chair of EAI’s Trade, Technology, and Transformation Research Center and Professor at Chung-Ang University), Taedong Lee (Professor at Yonsei University), Yul Sohn (President of EAI and Professor at Yonsei University).

[2] Peter Katzenstein, A World of Regions: Asia and Europe in the American Imperium (Ithaca: Cornell University Press 2005); Mary Farrell, Bjorn Hettne, and Luk Van Langenhove (eds), Global Politics of Regionalism (London: Pluto 2005); Fredrik Soderbaum, Rethinking Regionalism (Baisingstoke: Palgrave 2016); and Maria Lagutina, “The Global Region: A Concept for Understanding Regional Processes in Global Era,” The Journal of Cross-regional Dialogue (2020 Special Issue).

■ Yul Sohn is president of EAI and professor at the Graduate School of International Studies (GSIS) and Underwood International College at Yonsei University. He received his Ph.D. in political science from the University of Chicago. He previously served as the dean of Yonsei University GSIS, president of the Korean Association of International Studies, and president of the Korean Studies of Contemporary Japan. His research focuses on the Japanese and international political economy, East Asian regionalism, and public diplomacy. His recent publications include Japan and Asia's Contested Order (2018, with T.J. Pempel), and Understanding Public Diplomacy in East Asia (2016, with Jan Melissen).

■ Typeset by Hansu Park, Research Assistant

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | hspark@eai.or.kr

Center for National Security Studies