![[Asia Democracy Issue Briefing] The Role of Korea’s Election Commission and the Quality of Elections](../images/bg_tmp.jpg)

[Asia Democracy Issue Briefing] The Role of Korea’s Election Commission and the Quality of Elections

Commentary·Issue Briefing | 2021-10-29

Woo Chang Kang

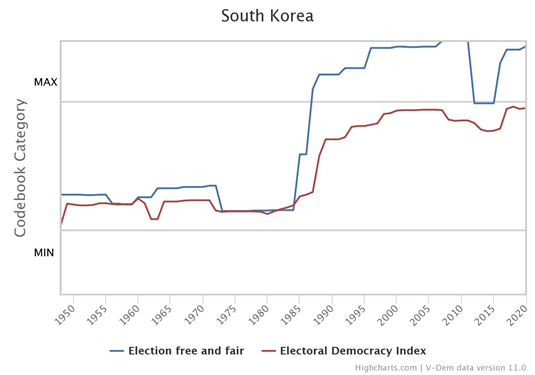

According to the Varieties of Democracy Institute, the freedom and fairness of South Korea’s elections have improved dramatically since the country first democratized. Figure 1 below shows how the quality of South Korea’s elections has changed between 1948 and 2020 (“election was free and fair” is indicated in blue) and the country’s rating on the Electoral Democracy Index (indicated in red). There was little change in election quality and the democracy index in the 40 years that followed the constitutional election of 1948. With the change to a direct election system implemented in 1987, the freedom and fairness of South Korea’s elections shot up, and the country’s rating on the democracy index increased greatly as well.

The primary factors that affect election quality can generally be categorized into structures, systems, and actors. Structural factors include economic development, political and social divisions, and geopolitical positions. The institutional factors of an independent judiciary and supervising body also play an important role in the oversight and control of the constitutional and legal basis and election processes supporting the separation of powers. At the actor level, the capacity and strategic choices of the government and members of the opposition forces including political elites, civil society, and the media, affect the quality of elections. In addition, voter perceptions of election quality may depend on whether the party or candidate they supported won or lost the election. Korea’s economic development was achieved during a time when social inequality was relatively low.

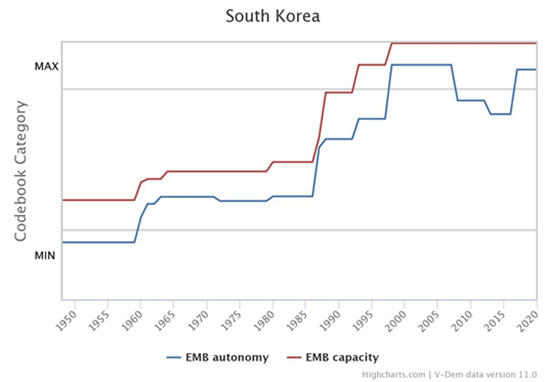

Although political conflicts based on regionalism existed, there were no violent confrontations or conflicts between members of society, or civil-war level religious, ethnic, or cultural conflicts. Further, following democratization, the peaceful transfer of power between Kim Young Sam (conservative) and Kim Dae-jung (liberal), Roh Moo-hyun (liberal) and Lee Myung-bak (conservative), and Park Geun-hye (conservative) and Moon Jae-in (liberal) increased the ability of the opposition to check the government and made it difficult to mobilize administrative control, further improving the quality of elections. A broad social consensus on regime change through elections was formed through this process. Finally, we cannot leave out the growth of the country’s capacity for election management. Figure 2 shows Korea’s ability to manage elections. This figure illustrates that the improvements in the freedom and fairness of elections go hand in hand with the changes in the autonomy and capacity of the National Election Commission (NEC).

Korea has a fundamentally high state capacity, and its bureaucratic capacity is also the best in the world. The resident registration system in particular has been the basis for effective and efficient election management by facilitating easy identification of voters compared to other countries where eligible voters have to be identified and registered. This article will focus on the capacity of the NEC in terms of the constitutional and legal status, organizational capacity, and the capacity and motives of its members.

I. The Neutrality and Independence of the NEC

The electoral process includes "the establishment of election laws, planning of electoral districts, confirmation of election schedules, voter confirmation, party registration, candidate registration, election campaign management, provision of election information to voters, management of election costs and political funds, oversight of ballot casting, vote counting and tallying, confirmation of election results, and dispute resolution" (Eum Sun Pil, 2015). Therefore, election management means executing and supervising the election process to ensure that free and fair competitive elections take place. However, different countries place different parts of the election process under the management of election commissions. In Korea, the role of the NEC includes the creation and oversight of the electoral register, registration of political parties and candidates, election campaigns, voting, ballot counting and tallying, and certification of election results. Election laws and the drawing of electoral districts fall under the authority of the National Assembly, and election-related disputes, in principle, fall into the jurisdiction of the courts.

Elections are the process of reorganizing the administration and legislature according to the will of the people. Election management can affect the election process and results. If election management is affected by political interests, then trust in the fairness of elections is weakened. Therefore, election management must be carried out by an independent organization free from political interests, including the interests of the administration, and the organization must have the administrative capacity to efficiently handle the entirety of the vast electoral process, from keeping track of eligible voters to calculating election results.

The Korean Constitution guarantees neutrality and independence of the election commission members. Following the establishment of the Korean government, the administration established an "election commission" within the executive that controlled elections. Historical reflection on the fraudulent 3/15 election of 1960 led to the establishment of the National Election Commission, a constitutional body independent of the executive, judiciary, and the National Assembly, in the third revised Constitution. Since then, the independence and neutrality of the NEC has been strengthened with each revision of the Constitution, with an exception to the revision made in 1972. The third revised Constitution in 1960 only stipulated how the NEC was to be composed, delegating matters related to organization, authority, etc. to the purview of the law. However, since then, rights, term lengths, political neutrality, status guarantee, rule-making authority, and details regarding the relationship between the NEC and various levels of administrative agencies have also been included in the Constitution. The Constitution goes beyond symbolically and declaratively defining the NEC as neutral and independent. It also attempts to lay the foundation for practical independence by providing the NEC with a basis for its activities. This is because even if the NEC's authority is mandated at the constitutional level, if its composition and operations are left to be decided at the legal level, the independence and neutrality of the NEC may be affected by changing political forces as determined by election results. The current Constitution gives the NEC the following powers and duties.

Article 114

(1) Election commissions shall be established for the purpose of fair management of elections and national referenda, and dealing with administrative affairs concerning political parties.

(2) The National Election Commission shall be composed of three members appointed by the President, three members selected by the National Assembly, and three members designated by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. The Chairperson of the Commission shall be elected from among the members.

(3) The term of office of the members of the Commission shall be six years.

(4) The members of the Commission shall not join political parties, nor shall they participate in political activities.

(5) No member of the Commission shall be expelled from office except by impeachment or a sentence of imprisonment without prison labor or heavier punishment.

(6) The National Election Commission may establish, within the limit of Acts and decrees, regulations relating to the management of elections, national referenda, and administrative affairs concerning political parties and may also establish regulations relating to internal discipline that are compatible with Act.

(7) The organization, function and other necessary matters of the election commissions at each level shall be determined by Act.

Article 115

(1) Election commissions at each level may issue necessary instructions to administrative agencies concerned with respect to administrative affairs pertaining to elections and national referenda such as the preparation of the poll books.

(2) Administrative agencies concerned, upon receipt of such instructions, shall comply.

Article 116

(1) Election campaigns shall be carried out within the scope prescribed by law under the management of the election commissions, but equal opportunity shall be guaranteed.

(2) Except as otherwise prescribed by law, expenditures for elections shall not be imposed on political parties or candidates.

II. The Capacity of the Election Commission

Korea’s NEC maintains the independence of its personnel by independently managing the recruitment, promotion, appointment, and transfer of its employees. According to the 2020 Ministry of Personnel Management statistics yearbook, the number of official positions at the NEC is 2,867, while the current number of actual staff employed is 3,085. Compared to the executive (1,078,516) and the judiciary (17,751) branches, the number of people is small, but these figures only reflect permanent employees. Table 1 uses data from the Electronic Learning and Capacity Training conducted by the Electoral Integrity Project in 2016 to compare the size of election management organizations in different countries. According to Table 1, Mexico has the largest number of permanent employees among the countries surveyed, with a staff of about 15,000. It is followed by Iraq (4,000), Panama (3,000), and Korea. Looking at the number of temporary hires employed during the election, Korea has one of the highest employment rates with about 200,000 people during elections followed by to Afghanistan and Thailand, which hire more than one million people, Indonesia (550,000 people), Kenya (300,000 people), and Tanzania (250,000 people). In addition, it was found that Korea rarely relies on unpaid volunteers.

The Organizational Capacity of Election Commissions by Country

|

Country |

Permanent staff |

Additional staff |

Additional staff |

Does EMB use unpaid volunteers during elections |

|

Afghanistan |

455 |

1155859 |

0 |

Never |

|

Argentina |

80 |

100 |

35 |

Never |

|

Bahamas |

18 |

10 |

75 |

Never |

|

Bhutan |

171 |

126 |

126 |

Never |

|

Cambodia |

300 |

7000 |

200 |

Rarely |

|

Canada |

328 |

231 |

1 |

Never |

|

Costa Rica |

900 |

300 |

0 |

On a regular basis |

|

Cote d'Ivoire |

301 |

537 |

60000 |

Rarely |

|

Dominica |

5 |

800 |

4 |

Occasionally |

|

Ghana |

2000 |

1000 |

|

On a regular basis |

|

Guam |

14 |

330 |

30 |

On a regular basis |

|

Guinea |

25 |

2442 |

684 |

Occasionally |

|

Indonesia |

40 |

547073 |

0 |

Rarely |

|

Iraq |

4000 |

300 |

100 |

On a regular basis |

|

Kenya |

868 |

300000 |

0 |

Never |

|

Rep. of Korea |

2800 |

200000 |

0 |

Rarely |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

164 |

30 |

7000 |

Rarely |

|

Malawi |

280 |

90000 |

30 |

Never |

|

Maldives |

60 |

4800 |

3900 |

Never |

|

Mexico |

15000 |

65000 |

0 |

Never |

|

Mongolia |

30 |

20000 |

10000 |

Never |

|

Mozambique |

500 |

48000 |

170 |

Rarely |

|

New Zealand |

106 |

18018 |

11 |

Never |

|

Palestine |

100 |

200 |

0 |

Rarely |

|

Panama |

3000 |

1000 |

200 |

On a regular basis |

|

Peru |

150 |

100 |

50 |

Never |

|

Rwanda |

50 |

75000 |

0 |

On a regular basis |

|

Samoa |

45 |

10 |

1500 |

Never |

|

Sao Tome and Principe |

32 |

54 |

|

Occasionally |

|

Senegal |

14 |

18163 |

11972 |

Never |

|

Sierra Leone |

200 |

40000 |

0 |

Never |

|

Suriname |

19 |

700 |

10 |

Never |

|

Tanzania |

143 |

250000 |

43 |

Never |

|

Thailand |

2000 |

1000000 |

2000000 |

Never |

|

Zimbabwe |

490 |

100 |

100000 |

Rarely |

Interestingly, except for Korea, the countries that employ a large number of permanent or temporary staff differ. Mexico, which employs the largest number of permanent employees, employs only about 65,000 temporary workers, and Afghanistan, which has an overwhelming number of temporary workers, has only 455 permanent employees. In contrast, Korea hires relatively more permanent workers as well as temporary workers to perform regular administrative and legislative election management tasks.

Such institutional and organizational capabilities of the NEC help the organization perform both its regular work and election management tasks effectively. Korea’s NEC has been entrusted with a variety of election tasks since 2005, including the oversight and operation of union leader elections for the National Forestry Cooperative Federation, the National Agricultural and Livestock Industry Cooperative Federations, and the National Federation of Fishery Cooperatives; following the legal institutionalization of corporate restructuring, general shareholders' meetings of private corporations; elections for national university chancellors; selections of executives for the Korean Federation of Community Credit Cooperatives; and union leader elections for apartment cooperatives. The consistent oversight and management of peacetime elections has helped further strengthen the capacity of the NEC. The NEC also introduced early voting in 2014, making it possible for voters to cast their ballot no matter what city or region they happen to reside in and greatly increasing the convenience of elections. The Commission additionally instituted electronic counting, reducing the potential for post-election by counting and announcing ballot counts in a prompt, public manner. An example of this is Korea’s presidential and legislative elections. The voting and ballot counting are broadcast in real time on election day, and election results are announced within 10 hours.

Next, Table 2 shows the degree of recognition that employees of the NEC have of the Commission’s independence and expertise. In terms of independence, Korea’s NEC scored 100 points along with Afghanistan and Costa Rica, but in terms of expertise, it scored 80 points after Bhutan, Malawi, Mexico and Peru. The results show that Korea’s NEC has a relatively positive assessment of its capacity compared to that of other election commissions. Of course, it is worth keeping in mind that Canada and the Netherlands, which are known to have high quality elections, were scored relatively low with regard to independence and expertise, while Mexico and Bhutan, which were rated highly for independence and expertise, received relatively low scores on the quality of their elections. This difference may simply be reflecting the stricter standards applied by New Zealand and Canadian election officials in their self-evaluations as compared to the standards applied by Mexican and Bhutan employees in evaluating their independence and expertise (Jaedong Choi and Jinman Cho, 2020).

The Independence and Professional Capacity of Election Commissions by Country

|

Country |

INDEPENDENT |

PROFESSIONAL |

|

Afghanistan |

100 |

60 |

|

Argentina |

20 |

60 |

|

Bahamas |

0 |

60 |

|

Bhutan |

80 |

100 |

|

Cambodia |

40 |

0 |

|

Canada |

20 |

40 |

|

Costa Rica |

100 |

80 |

|

Cote d'Ivoire |

20 |

80 |

|

Dominica |

80 |

40 |

|

Ghana |

60 |

60 |

|

Guam |

20 |

20 |

|

Guinea |

20 |

40 |

|

Indonesia |

60 |

60 |

|

Iraq |

60 |

60 |

|

Kenya |

60 |

80 |

|

Rep. of Korea |

100 |

80 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

20 |

60 |

|

Malawi |

80 |

100 |

|

Maldives |

80 |

40 |

|

Mexico |

80 |

100 |

|

Mongolia |

20 |

80 |

|

Mozambique |

40 |

60 |

|

New Zealand |

40 |

80 |

|

Palestine |

20 |

60 |

|

Panama |

80 |

60 |

|

Peru |

80 |

100 |

|

Rwanda |

20 |

40 |

|

Samoa |

40 |

60 |

|

Sao Tome and Principe |

40 |

20 |

|

Senegal |

80 |

40 |

|

Sierra Leone |

60 |

80 |

|

Suriname |

0 |

40 |

|

Tanzania |

60 |

80 |

|

Thailand |

40 |

60 |

|

Zimbabwe |

60 |

60 |

The positive self-evaluation of the independence of Korea’s NEC reflects the historical experience of the Commission members. For example, in 1964, the year after the NEC was created, President Park Chung-hee went to inspect the NEC during his annual new year’s inspection of government departments, but President of the NEC, Sa Kwang-wook, refused to allow the visit, saying it was not appropriate for the executive to visit agencies that were designated as independent under the Constitution. In addition, during the National Assembly by-elections in Donghae City in 1988, Lee Hee-Chang, President of the NEC, filed a simultaneous complaint with the prosecutor's office regarding all five candidates and the election manager in a show of his strong will to have fair elections. This was the first case in the history of the NEC wherein the Commission charged a candidate, and later served as an opportunity to raise public interest in the NEC’s work through the media and engender positive public opinion on the importance of fair election management. These experiences are good examples of the importance of not only the legal and institutional foundation of the NEC but also the active will of the Commission’s members in maintaining the organization’s independence.

III. Fair Elections

The public's trust in political organizations reflects whether or not these political organizations are living up to the public’s expectations. The trustworthiness of the NEC is assessed subjectively by voters on the basis of the NEC's activities. Therefore, when the public recognizes that the NEC contributes to improving election quality, public trust in the organization will increase. This trust in turn creates a basis for the National Election Commission to effectively carry out its management and oversight tasks during future elections.

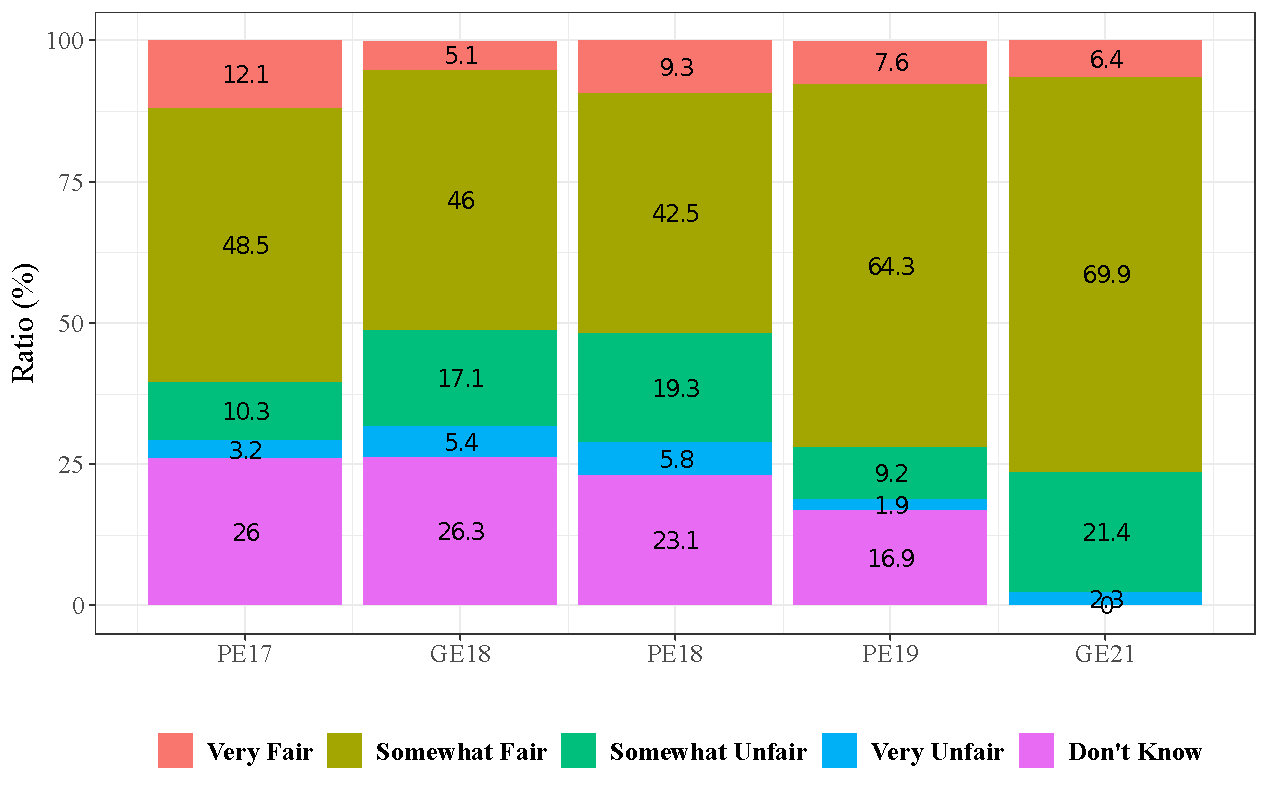

The Korean public generally has a favorable opinion of the NEC. According to Cho Jinman, Kim Yong-cheol, and Cho Young-ho (2015), 71.4% of the public trusted the National Election Commission during the 2012 presidential election. The results of the World Values survey conducted around the same time showed that public trust in the National Assembly was just 24%, 26% for political parties, and 46% in the executive branch of the government. In comparison, trust in the NEC was relatively higher. Figure 3 shows voter perceptions of how fair the NEC’s monitoring and enforcement actions during elections are. In the seventeenth presidential election held in 2007, 61% said the NEC’s actions were fair. Despite the aftermath of the National Intelligence Service's manipulation of public opinion during the eighteenth presidential election, about 52% of the public gave the NEC a positive rating, and similar figures were recorded during the eighteenth general election. Seventy-two percent of the public positively rated the NEC’s activities In the nineteenth presidential election that followed the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye, and the proportion of positive respondents in last year's twenty-first general election rose to 76%.

IV. Restrictions on Freedom

However, unlike the function and role of the NEC in ensuring fair elections, which has received quite positive feedback, there are concerns that the restrictions placed on elections by the NEC, especially with regard to election campaigns, are overly limiting. Article 58 of the Public Official Election Act defines election campaign activities as an “action to be elected, or to facilitate or prevent the election of a person,” and regulates all campaign matters including campaign durations, who may perform election campaign activities, how election campaign activities can be performed, and the criteria for examination (Cho YoungSeung 2018). The Article contains very detailed and complex regulations on election campaigns, such as stipulating the allowed and disallowed campaign period, who can and cannot campaign, and what types of campaign activities are and are not allowed. However, as information and communication technology advances and the desire of voters to express their political opinions increases, criticisms have been raised against the Public Official Election Act, stating that the blanket application of election management regulations restricts the freedom of expression. For example, the NEC decided ahead of the 2021 special election that advertisements placed by ordinary voters in daily newspapers calling for the unification of opposition candidates and the "Why have a special election" campaign run by women's organizations were in violation of the Public Official Election Act. The current law prohibits the posting, distribution, or installation of facilities or print materials supporting, recommending, or opposing specific political parties and candidates by banning paper banners and ads between 180 days prior to Election Day and Election Day itself. Another example is the NEC’s request to delete 17,101 online posts made ahead of the twentieth National Assembly election in 2018. A civic group performed an analysis on the posts which were targeted for deletion and found that the majority of the posts simply cited polling results or were critical of candidates with regard to verifying their qualifications. The civic group criticized the deletion of these posts as a violation of the right to know and freedom of expression of voters.[1]

In response to these criticisms, the National Election Commission stated that the decisions on violations of the election law were "to ensure equal opportunities for candidates to campaign and prevent the fairness of elections from being violated by illegal activities."[2] Despite the criticisms that the Public Official Election Act violates election freedom, this statement from the NEC is consistent with the Constitutional Court's view that the Public Official Election Act is generally constitutional. Article 116(1) of the Constitution stipulates that equal opportunities should be guaranteed for candidates in election campaigns, and Article 1 of the Public Official Election Act stipulates that “elections should be conducted fairly through the free will of the people and democratic procedures, and election-related corruption must be prevented.” This focus on fair election management is not irrelevant to the fact that the NEC was established in the Constitution as an independent organization following the corruption in the 315 elections to ensure freedom and fairness in elections. Every time a complaint has been filed against the Public Official Election Act on the grounds that it is unconstitutional, the Constitutional Court has ruled that restrictions intended to prevent election campaigns from overheating and incurring socio-economic losses, or to stop unfair situations from arising wherein campaign opportunities are unbalanced due to economic differences between candidates, do not violate freedom of political expression (Kim Hwan-il, Hong Seok Hwan 2014).

However, following the institutionalization of free and fair elections after democratization, there has been a consensus that Korea’s overly detailed regulatory election management has not been able to keep up with the heightened political consciousness of the public and the other changes of the times. Reflecting this, in April of 2020, the NEC submitted an amendment to the Public Official Election Act to expand political expression through the abolition of Articles 90 and 93(1) of the Public Official Election Act, which comprehensively banned the posting, transmission, and distribution of facilities and printed materials that could influence an election for the 180 days preceding election day. In May of the same year, a revision to the Political Relations Act was submitted to the National Assembly to expand the campaign period for prospective candidates and allow the establishment of gu, city, and county-level parties to boost participation in political parties. However, the amendment also includes provisions for the transparent management of political funds to prevent past harms. If these efforts lead to actual revisions of the laws, voters may participate more actively in the election process, and conditions could be created for political parties and candidates to engage in more diversified political competition with increased accountability.

V. International Democracy Aid

The Korean Election Commission has made efforts to improve their overall election management capabilities and spread the values and norms of democracy necessary to hold free and fair elections by sharing the experiences and knowledge of Korean democracy with new democracies. In particular, in 2014, he led the creation of the Association of World Election Bodies (A-WEB) and established its headquarters in Songdo, Korea. As of 2021, 118 election management bodies from 108 countries from around the world are participating members. Korea, as the leading founding country, provides various supports for the operation of A-Web such as financial support. Members include the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), National Democratic Institute, Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) and other international organizations that cover election management. These members cooperate with civil society organizations to run various programs to strengthen the election capabilities of new democratic countries. For example, the Election Management and Capacity Building Program focuses on fostering expertise for election officials to cope with possible problems in the election process, and the Specialized Training Program on ICT aims to enhance their understanding of how to use information and communication technology in election management system and operation. In addition, the Election Visitor Program provides election officials with the opportunity to experience and observe election management processes in other countries. These programs provide opportunities for election officials in each country to understand different election systems, share and spread better election management techniques, and contribute to seeking an election management system suitable for each country's situation.

VI. Conclusion

This article attempted to clarify how Korea’s National Election Commission has contributed to improving the quality of Korean elections. The NEC has been guaranteed its independence and neutrality by the Constitution on the basis of strong state capacity and bureaucracy. In addition, the NEC is relatively rich in terms of the human and material resources necessary for election management compared to election commissions in other countries. Members of the NEC have worked to maintain the independence and neutrality of the organization even amid institutional changes, and worked hard to hold fair elections. As a result, the NEC enjoys a higher degree of public trust compared to the National Assembly and the national government and receives positive ratings on the fairness of the elections that it manages. The demand for the new role of the NEC and an externally the call for Korea to contribute to the promotion of global democracy based on its democracy success experience has increased due to the maturity of Korean democracy and the changes of the domestic political environment. The following are just some strategies that should be further examined

First, a legal institutional framework should be established to guarantee the freedom of campaigning from regulatory-oriented election management. After democratization, during the process of establishing procedural democracy, there were concerns of government intervention and financial influence on elections. Therefore, the agenda of the NEC prioritized securing a fair election process. However, various forms of campaigns have emerged due to the increase in the public’s desire for political participation due to the diversification of society and due to the development if information and communication technology. It is difficult to clearly determine whether or not these new forms of campaigns are restricted under the existing Public Official Election Act. As a result, the effectiveness of a “positive” campaign regulation that only allows the method of campaigning as prescribed by law is decreasing. In the future, matters to be prohibited during the election campaign should be specified by law. However, actions that are not prohibited by law should be converted into a comprehensive “negative” type of election management that focuses on and allows for candidates and parties to freely campaign fulfill the voter’s right to knowledge and a t the same time create a space that allows voters to express their opinions freely. Additionally, it is necessary to enhance the people’s right to knowledge and political rights by strengthening the transparency of political funds through the regular disclosure of income and expenditure of political funds.

Second, democratic citizenship education should be strengthened. The quality of elections and democracy is closely related to civic culture. The quality also improves when voters cultivate consciousness and ability as democratic citizens and when civic culture is established through society as a whole. Pre-WWII Germany was thought to have one of the most deeply rooted authoritarian cultures in the world. However, studies have shown that, as constitutional and reforms were implemented, German civil culture began to outpace the U.S. by the 1970s. The German case is a good example of how democratic citizenship education can form civic culture and improve the quality of democracy. Korean voters’ civic consciousness and Korean citizenship culture have also improved substantially compared to the past, but research and education on democratic citizenship education, including media literacy, need to be established to effectively cope with the flooding of fake news and polarization. Furthermore, these experiences can be important assets that Korean democracy cans share with new democracies. In the case of new democracies, conflicts between tribes or religions often appear in the form of violence, not voting. Therefore, it is necessary to improve civic awareness through democratic citizenship education that can cultivate a basic understanding of the value of elections and voting, dialogue and compromise. Currently, there are education programs available for election officials in developing countries but in the future the target for these programs should be expanded to the general public.

Third, more research is needed on the experiences and achievements of Korean democracy. Although extensive research on specific areas such as election law, party law and election management has been conducted until now, very little research has been done on the comprehensive, political and empirical perspective of election governance. Therefore, support and help from academia as well as various institutions such as the election commission, research foundations, and think tanks is needed. In particular, it is necessary to establish a system that can efficiently manage and share statistical data to empirically analyze Korean democracy. Currently, data related to the National Assembly and the legislative process are produced by the National Assembly and data related to the election process and results are produced by the NEC. However, there is not system for systematically managing, disclosing and disseminating data. This demonstrates a common issue that is present in Korean democracy aid in constructing data. Since the enforcement of the Data 3 Act in August 2020, studies using administrative information that has undergone de-identification process have been actively conducted in areas such as health, medical care, and finance. It is necessary to consider ways to apply this development to elections and political fields.

Fourth, legal foundation and financial support are needed to establish a system that can continuously contribute to the development of global democracy based on Korea’s democratic experience. Through various programs and projects, Korea is contributing to the democratic governance of the international community. However, a limitation is that current ongoing projects are carried out individually and segmented into different subjects. Establishing a legal basis for democracy aid can contribute to planning and proceeding with projects from a more systematic and long-term perspective. Additionally, the recent decrease of education for committees due to the budget cut of the World Economic Commission shows that stable financing is essential for continuous aid projects.

Fifth, it is necessary to establish a network and expand partnership with a third party international organization, international NGO and civil society of the aid recipient country. Election management is closely related to the political situation of each country and efforts to establish democratic governance often requires national legal and institutional reform. Therefore, there is a limit of how directly the Korean or other foreign government can lead the aid projects. In order to effectively carry out aid programs, cooperation with international organizations and NGOs is necessary. Creating connections with the local civil society is especially crucial as they can be a partner for the aid projects. In the case of new democratic countries the capabilities of the local civil society is also limited. Therefore, the civil society of the aid recipient country should be supported to strengthen their capacity to discover and publicize various problems of democratic governance.■

References

Cho Jinman, Kim Young Cheol, Cho Yeong Ho. 2015. “Assessing the Quality of Elections and Trust in the National Election Commission.” Korean Journal of Legislative Studies 21(1). 165-196

Cho YoungSeung. 2018. “A study on the guarantee system of freedom of election campaign- Constitutional grounds and protection area.” Public Law Journal. 19(2). 155-183.

Choi Jaedong, Cho Jinman. “Do National Election Commission's Institutional Design and Workforces Have an Impact on Electoral Integrity?” Journal of Parliamentary Research. 15(2): 145-170.

Dahl, Robert A. 1998. On Democracy. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

Eum Sun Pil. 2015. “Status and Roles of Election Commissions in the Korean Constitution.” Hongik Law Review. 16(1). 219-249.

Kim Il-Hwan, Hong Seok Han. 2014. “A Comparative Study on the Regulation of Election Campaign.” Study on the American Constitution 25(1). 31-63.

[1] People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy. https://www.peoplepower21.org/Politics/1451265 (Accessed 2021/9/7)

[2] National Election Commission https://m.nec.go.kr/site/nec/ex/bbs/View.do?cbIdx=1090&bcIdx=144141 (Accessed on 2021/9/7)

■ Woo Chang Kang is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Korea University. His research interests are in political behavior and quantitative political analysis, with particular attention to Korea and the United States. He received his Ph.D. in politics at New York University, and previously taught at the Australian National University.

■ Typeset by Ha Eun Yoon Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | hyoon@eai.or.kr

Center for Democracy Cooperation

South Korea Democracy Storytelling