![[Asia Democracy Issue Briefing] The Implications of Korea’s Experience Supporting Democracy as a Global Narrative](../images/bg_tmp.jpg)

[Asia Democracy Issue Briefing] The Implications of Korea’s Experience Supporting Democracy as a Global Narrative

Commentary·Issue Briefing | 2021-10-14

Taekyoon Kim

[Editor's Note]

With many developing countries in need of help in settling democratization processes and systems, Korea is in a position to act as a bridge between developed and developing countries by sharing its knowledge and experience in democracy and political reform. Taekyoon Kim, a professor at Seoul National University, describes the main contents of Korea’s democratic aid, how to share the Korean democracy experience and the challenges and strategies for Korean democracy in the future. Through this, the author states that the direction of Korea’s democracy should move forward based on its experience and that Korea should use its democratic aid as an asset so that Korea can be recognized as a symbol of peace and democracy in East Asia.

I. The Position of South Korean Democracy in the International Community

South Korea became a part of the club of developed donor countries when it joined as a member of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) in 2010. In 2021, Korea was removed from the list of developing countries and added to the list of developed countries during the 68th UN Trade Development Conference (UNCTAD). Korea's improvement in status in the international community is often explained by focusing on the country’s rapid economic growth, with Korea’s GDP ranking in the top ten countries globally in 2021. However, efforts to shed new light on Korea's role in the international community by focusing on the country’s history and experience of democratization and political development that accompanied economic development are still in need of supplementation. The international community is just as interested in Korea’s democratization as it is in Korea’s economic miracle. Many developing countries hope to receive guidance in their own democratization and improvement in institutions through the sharing of Korea’s experience in the democratization process and implementation of democratic systems.

In many respects, Korea is in a position to share its knowledge and experience in democracy and political reform with developing countries and to provide a bridge between developed and developing countries. To start, like most developing countries in the Global South, Korea has endured colonialism, become independent, and undertaken the project of nation-building. When World War II ended in 1945, Korea became independent and established the First Republic in 1948, at which time the country was divided and embarked on nation-building. These experiences are likely to be the same as those of many developing countries. Second, Korea endured a three-year-long civil war beginning in 1950 and can share its experience of peacebuilding and development with developing countries that have endured similar civil conflicts or clashes. Third, Korea experienced military coups in 1961 and 1979, respectively, as well as a military dictatorship, and the consolidation of democracy after the 1987 democratization. Telling the story of how Korea’s civil society grew and the country’s democratic consolidation will provide important perspectives on potential solutions to problems such as the recent military coup in Myanmar and subsequent democratic crisis, and the military dictatorships and government corruption easily found in Africa. Finally, Korea's historical path, which is compressed into the division of the two Koreas and the efforts to build peace on the Korean Peninsula, has the potential to offer its experiences to countries that are faced with ideological conflict.

As such, the narrative of Korea’s compressed modern and contemporary history spanning colonialism and independence, war and restoration, military dictatorship and democratization, and division and peacebuilding will offer attractive experience and knowledge to partner countries in the Global South. Korea is the only country in the world that has transformed from a developing to a developed country in a relatively short period of time in terms of political development and democracy. This is why there is a growing number of requests for Korea to mediate between the groups of developed and developing countries, and growing interest from developing countries to learn from Korea’s know-how to drive the reform of political systems.

Telling the stories of Korea's experiences in political development and democracy and telling stories that reflect Korea’s political development and democratic experience to support developing countries are rather different in nature. As the former case is Korea’s internal political and historical narrative, it is not necessary to consider the relationship with a third partner developing country, while in the latter case, Korea’s position as a donor country and the third partner developing country’s position as a recipient country should be considered. Since the sharing of Korea’s democratic experiences has not been centered in overseas aid as a key issue like economic and social development, it has yet to occupy a mainstream position in Korea's official development assistance (ODA) and other international cooperation projects. The reason why experience sharing of democracy has not been a key agenda for Korea’s ODA is because political agendas such as democratization, peace, and human rights have not been recognized for their importance compared to economic development/ social development sectors. Additionally, the fact that the term “democracy aid” is itself politically sensitive is another reason. The possibility of donor countries demanding democratization as aid conditionality before providing aid or democracy aid being used as political intervention to instill the donor country’s democratic values cannot be ruled out. In fact, there are many instances of uncomfortable truth in which powerful countries like the US have a history of unilaterally supporting democracy aid with the aim of democratizing authoritarian developing countries. In other words, democracy and political institutionalization are cultural products and political processes that occur naturally depending on the local conditions of the recipient country, not projects that can be imported and transplanted from abroad. Thus, it can be said that the sharing of Korea’s democratic experiences has not received systematic attention from Korean international development cooperation agencies and academia due to having been treated as relatively insignificant in comparison to economic/social development and due to the political sensitivity of democracy aid itself.

Nevertheless, although Korea does not conceptually distinguish democracy aid, it has been implementing development cooperation projects to cultivate values related to democracy and improve institutions, such as strengthening the governance capabilities of governments in developing countries and the capacity of civil society. Although Korea is not yet operating an integrated system for democracy aid, as each development cooperation agency has contributed to improving the democratic system in developing countries in different ways, there will be an important significance in organizing the contents of democratic aid and sharing method at the current stage and the limitations and future improvements to share Korea’s democracy aid experience as a single narrative.

II. The Main Contents of Korean Democracy Aid and Implementing Agencies

Following the end of World War II, democracy aid established itself as a foreign aid policy to transform the political systems of US-centered allies and friends into democracies. As shown in Table 1 below, various conceptual analyses and theoretical and empirical studies share an approach that divides the components of democracy aid into election processes, state agencies and institutions, and civil society areas. This approach focuses more on content related to the establishment, reconstruction, and solidification of the democratic system in recipient countries than on donor countries providing democratic values and political ideologies to recipient countries. Having itself transformed from a recipient to a donor country, from a developing to a developed country, and from a military dictatorship to a democracy within a brief period of time, Korea has shown the strength of its development cooperation regarding knowledge sharing and training projects related to institutional maintenance. In fact, Korea has thus far focused the content of its democracy aid within this scope, strengthening the capacity for management and sustainability as well as the improvement and maintenance of instrumental systems. In other words, development cooperation projects have been planned to support democratic institutions by improving public administration and election systems. In the civil society sector, support for civil society organizations (CSOs) in recipient countries strengthened the advocacy role and service delivery functions of these organizations. With the declaration of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) began to promote stronger cooperation on its multi-layered SDG16 programming strategy based on its link with the components of democracy aid (law, institution building, peace, accountability, etc.) with a particular focus on implementation.

Template for Democracy [1]

|

Sector |

Sector Goals |

Method of Aid |

Korean Aid Organizations |

|

Election Process |

ㆍFree and fair elections |

ㆍElection support |

ㆍNational Election Commission (A-WEB) |

|

State Institution |

ㆍDemocratic constitution and rule of law |

ㆍSupport the building of a constitutional system |

ㆍKorea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) |

|

Civil Society |

ㆍStrengthen the advocacy of NGOs |

ㆍSupport for citizenship education |

ㆍKOICA |

In Korea, democracy aid has not yet been discussed within the domain of ODA. In addition, planned democracy aid projects within Korea have not yet been organized under a unified conceptual framework or system. Accordingly, each institution selects the content and scale of its budget for such projects very differently, making the dispersal of democracy aid appear quite segmented. Despite this segmentation, the donor targets and the methods through which Korea’s democracy aid is implemented can be categorized into three groups as shown in Table 1.

The National Election Commission (NEC) has become a key player and has shared Korea's experience and knowledge with election agencies in developing countries in an effort to improve their local election management capabilities. The NEC has also shared content supporting the improvement of election management systems and the establishment and development of democracy with countries that are undergoing democratic transitions. The NEC began its work supporting developing countries in 2006 with KOICA's consignment. In 2013, the NEC began to operate an invitational training program at the Korean Civic Education Institute for Democracy organized using the ODA budget. In 2014, the Association of World Election Bodies (A-WEB) was established in Incheon Metropolitan City, and A-WEB provided assistance to the invitational training program before taking it over completely in 2016. The training program primarily focuses on sharing the current status of election management and major issues in developing countries, sharing best practices for election management, inviting experts from international organizations to provide case analysis, and preparing an action plan to address the electoral management situation of each country. As shown in Table 2 below, the budget allotted to the NEC and A-WEB for the training program has been reduced by more than half since 2019, which is one factor reducing the sustainability of Korea’s democracy aid.

Budget Progression for Provision of Capacity-building Training in Developing Countries

|

Year |

Budget (million KRW) |

|

2014 |

250 |

|

2015 |

734 |

|

2016 |

837 |

|

2017 |

628 |

|

2018 |

933 |

|

2019 |

360 |

|

2020 |

360 |

|

2021 |

444 |

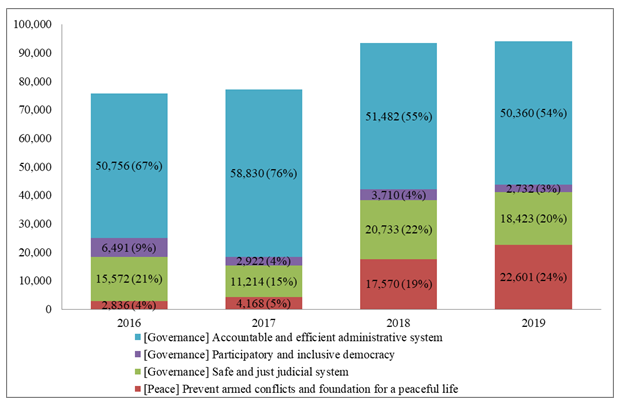

Second, regarding state institutions, Korea’s example can be summed up as grant-type ODA support for the public administration field and the judicial system of governments in developing countries. The main institution in Korea that plans and delivers democracy aid in the public administration field is KOICA. Since 2010, KOICA has strategized public administration as one of the key sectors of foreign assistance, but since 2021, public administration has been restructured into the field of "peace and governance" and detailed goals established for mid-term strategies. Currently, these detailed strategic goals consist of (1) the prevention of armed conflict and the creation of a peaceful foundation for living (peace), (2) the expansion of participatory and inclusive democracy (governance), (3) the building of a safe and just judicial and security system (governance), and (4) the building of an accountable and effective administrative system (governance). If the existing projects planned in the public administration sector focused on building administrative systems by improving the education and training system for public officials, modernizing administrative systems through e-government, and modernizing tax administration, the trend emerging in 2021 is the expansion of democracy aid to democracy promotion, peace, and other such areas. In this context, major programs are being planned to strengthen political accountability for the public by building a fair election and voting system, improving transparency by strengthening audit capabilities to prevent corruption, and enhancing the accessibility of administrative services for local residents by strengthening local administrative capacity. In addition, in order to improve the inclusivity of laws and institutions, key programs are being shared that promote the rule of law by strengthening the personnel and institutional capacity of the judicial sector, protect the human rights of women and vulnerable groups, strengthen security capacity to promote peace and create a safe society and ensure citizenship and social rights. As mentioned earlier, KOICA is planning content and implementation methods for its major programs in the field of peace and governance based on Korea's know-how in improving public administrative institutions, the core values of SDG16, implementation programming strategies, and the phased introduction of a human rights-based approach.

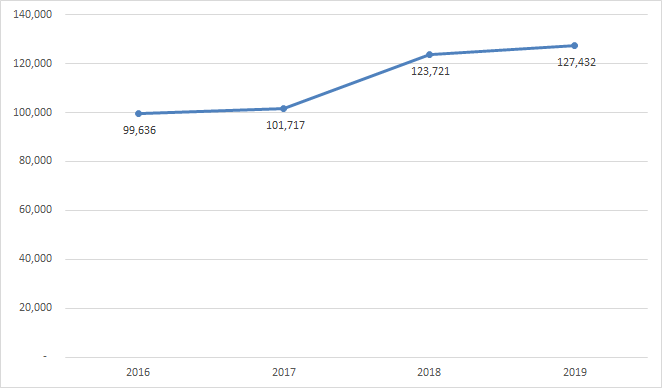

Figure 1 shows that the overall scale of support for KOICA's peace and governance programs has continued to increase over a four-year period (2016-2019). Looking at a breakdown of the figures by year, 15.6 percent of a total of 99.6 billion KRW was allocated to peace and governance in 2016, followed by 16.0 percent of 101.7 billion KRW in 2017, 18.1 percent of 123.7 billion KRW in 2018, and 16.9 percent of 127.4 billion KRW in 2019. On average, 16.7 percent was dedicated annually to peace and governance sector. The stable provision of 15 to 18 percent of the support budget to peace and governance sector means that there is sustainable demand for such programs from partner countries, and indicate the incredible importance of these programs to ensure a safe and sustainable living situation for individuals. Despite this fact, records show that KOICA's budget for the public administration sector in the 2000s accounted for about 23-24 percent of the total budget, meaning it is necessary to reconsider the current budget.

Looking at the percentage of the budget dedicated to the establishment and implementation of each sub-goal in the peace and governance sectors in 2021 in accordance with KOICA’s mid-term strategy compared to the total amount of support provided over the past four years (Figure 2), an overwhelming 81 percent of the total spent is in the legislative, judicial, and administrative sectors in service of governance goals including participatory and inclusive democracy, safe and just justice and security system, accountable and effective administrative institutions. In contrast, just 19 percent was spent in pursuit of the peace sector goals. If we examine the allocation of support among the various governance goals, we find that the majority (62 percent) was put towards the administrative (responsible and efficient administrative system) sector, followed by the judicial (safe and just judicial and security system) sector (19 percent) and the legislative (participating and inclusive democracy) sector (5 percent). The most important initiatives of KOICA’s democracy aid thus far have been its public administration capacity building to improve administrative institutions and the invitational training programs. Public administration and the improvement of administrative institutions are sectors where Korea has a comparative advantage.

In addition to KOICA, the Judicial Research and Training Institute, the Korea Institute of Public Administration, and local government groups provide active support for state agencies, government systems, and public administration of developing countries. The majority of this support is contributed at the invitational training program for civil servants in developing countries, with each organization contributing by sharing expertise and capacity building based on its own professional strengths. The Judicial Research and Training Institute, primarily achieves its goal of contributing to social integration, an independent judiciary, and the improvement of judicial systems of recipient countries. It achieves this through cooperation and exchanges with developing countries via ODA projects and foreign legal training targeting developing countries, generally held at the International Judicial Cooperation Center. In 2020, the Institute held training sessions and online seminars for trainees from Nepal and Uzbekistan. Similar to the Judicial Research Institute, the Korea Institute of Public Administration (KIPA) mainly conducts training programs for public officials from developing countries and joint research and consulting projects with domestic and foreign institutions. However, KIPA’s budget is significantly smaller than that of KOICA. Local governments, which generally operate on small budgets, have been increasing the number of international cooperation programs, having primarily focused on friendship exchanges with local governments in developing countries. In July of 2021, ODA Korea decided to award local governments an ODA support budget, and the governments receiving the money plan to expand their activities into the local government public administration sector.

Third, based on the benefits they received from overseas institutions such as Misereor, the Asia Foundation, and German EZE during the country’s democratization, Korea's CSOs have also been engaged in a variety of activities to support the work of civil society in developing countries. First of all, KOICA has a budget to support CSOs through a civil society cooperation program, which is being promoted as a project to improve the quality of life of residents of partner countries in cooperation with private partners including civil society, academies, and social economy organizations to reduce poverty and increase welfare in developing countries. The budget for this program has been continually increasing, with 26.7 billion KRW allocated in 2017, 27.1 billion KRW in 2018, 29.4 billion KRW in 2019, and 37.6 billion KRW in 2020. However, when KOICA's support for the public administration sector is viewed under the OECD DAC CRS codes, public policy and administrative management account for 41.86 percent of the total spent, while public administration accounts for 29.1 percent, totaling about 71 percent of the budget. In contrast, the budget for the main issues of democratic governance breaks down to 0.18 percent spent on elections, 0.37 percent on anti-corruption organizations and institutions, 0.44 percent on civic group strengthening, 0.23 percent on human rights, and 2.37 percent on gender equality. It is clear that outside of public administration, the budget for democratic governance, particularly civil society and cooperation, is quite small.

As one of Korea’s most well-known development cooperation consultative bodies, the Korea NGO Council for Overseas Development Cooperation (KCOC) is one of several key organizations contributing to the field of democracy aid in civil society. According to the KCOC, in 2019, 27 Korean development cooperation CSOs cooperated with local partner CSOs in developing countries on 111 projects in 31 countries, spending 6.8 billion KRW (97.3 percent) of their own funds and 180 billion KRW (2.7 percent) government funding. This confirms the minor scale of government funding for such projects. The Korea Democracy Association, which also works in the field of civil society, aims to strengthen its status as a key democratic organization contributing to the mutual promotion of international civil society, locate personnel from overseas who contributed to the Korean democratization movement and promote related commemorative projects, increase youth participation, and enhance international cooperation through democracy and public diplomacy. However, its budget for pursuing such goals remains small.

In order to support unions and the institutionalization of labor-management relations, the Korea Labor and Employment Service (KLES), which operates under the Ministry of Employment and Labor, has been implementing development cooperation projects in developing countries since 2011. The KLES carries out these projects by sharing their know-how on topics such as labor-management relations, labor policies, and policies to improve the labor environment. For international exchange and cooperation projects, the KLES provides support for overseas investors as well as professional services relating to labor and employment targeted at domestic companies that are or are planning to enter overseas markets. The KLES has also cooperated with the ILO on aid projects including employment education for foreigners, but with a budget set at 800 million KRW for foreign exchange and cooperation aid projects, these efforts are limited and suffer from a lack of funding.

Overall, the current democracy aid provided by Korea that falls into the category of development cooperation can be said to fit within election processes, state agencies/institutions, and civil society, which form the basic sectors in the internationally shared democracy aid template (Table 1). We can see that the primary democracy aid from Korea is in the form of knowledge-sharing and training programs on policy development and institutional improvements. However, at the same time, there are three problems to address. First, Korea's democratic experience is not being properly discussed and reflected in the current democratic governance aid being provided to different sectors. It is necessary to supplement the current content with narrative elements to tell the story of Korea's experience. Second, it is difficult to expect that an organic linkage or synergy effect will be created between the segmented aid provided for election processes, state agencies/institutions, and civil society. This is because individual aid entities do not jointly develop or integrate the planning and implementation of their aid content. Third, the small budget problem faced by all Korean organizations providing democracy aid highlights the mobilization of financial support from the government and civil society as a necessary condition for a future narrative project on the experience of democracy aid.

III. Methods of Sharing South Korea’s Democracy Experience

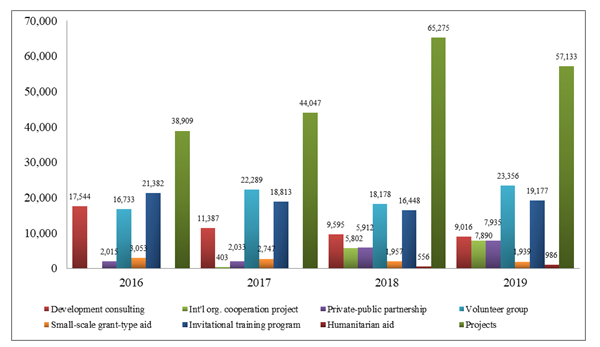

In addition to analyzing the democratic governance content provided by Korean development cooperation agencies, it is necessary to understand how said content is delivered to partner countries. For convenience, we will use the example of KOICA, the organization that delivers the majority of Korea’s democracy aid. The methods of democracy aid delivery to developing countries can be categorized as shown in Figure 3 below.

Looking at the scale of support by type of peace and governance program provided by KOICA over the four-year period between 2016 and 2019, we can see that project methods received 45.4 percent, invitational training programs got 16.8 percent, volunteer groups received 17.8 percent, development consulting was given 10.5 percent, public-private partnerships were given 4.0 percent, international agency cooperation projects got 3.1 percent, small-scale grant-type aid received 2.1 percent, and humanitarian aid received 0.3 percent of the total support. The majority of peace and governance programs are delivered in the form of projects. Development consulting, small-scale grant-type aid, and national cooperation projects together account for about 60 percent of the total. This means that most projects, such as establishing legal institutions and systems and improving institutions, are performed at the request of recipient country governments. In other words, partner country governments can officially request to receive the opportunity to improve their institutions from Korea using the country’s democracy experience. However, it is difficult to accurately grasp how often recipient country governments actually request grant-type support from the Korean government as a result of advanced sharing of knowledge of the specific details of Korea's democratic experience and the advocacy role of civil society. In addition, it can be said that the training program to strengthen the capacity of public officials indirectly provides democracy aid by actively improving awareness of democratic governance, human rights, and gender issues, and cultivating expertise on election systems, state institutions/public administration, and civil society.

Domestic CSOs have continued to criticize the low amount of democracy aid (4.0 percent) allocated for civil society cooperation and public-private partnerships. In 2019, the "Basic Policy of Government-Civil Society Partnership in the Field of International Development Cooperation" was signed, emphasizing that Korean civil society will contribute to the establishment of international development cooperation policies for donor and developing countries, ensuring the participation of the people in their implementation and the creation of a democratic society. To this end, the government plans to expand cooperation with civil society in developing countries and increase the budget allocated to support civil society public-private partnerships. There are plans to expand the efforts on the basis of this 2019 policy partnership to tell the story of Korea’s civil society so that they can share their knowledge of democracy and peacebuilding.

In addition to these national cooperation projects and support through civil society, democracy aid is also rendered by KOICA through cooperation with third-party partners. Two examples of this are KOICA’s humanitarian support and cooperation projects with international organizations. However, cooperation projects with international organizations are allocated just 3.1 percent of the total KOICA peace and governance program budget, while humanitarian aid receives 0.3 percent. For international cooperation projects, the UN organizations and multilateral development banks recommend that Korea share its historical experiences of economic and political development with other developing countries, create a development cooperation knowledge-sharing program (KSP), and expand the projects that it offers to developing partner institutions. Advanced donor countries prefer multi-bi methods, where aid is delivered through international organizations rather than given as direct support to partner recipient countries, and budgets for this type of aid are increasing. Since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an increased emphasis placed on untact methods of aid delivery, and as there is likely to be a similar emphasis on humanitarian and cooperation projects with international organizations going forward, it seems there will be an opportunity for Korea to actively connect its democracy aid experiences and know-how with multilateral aid provision. In addition, there is a need to diversify KOICA’s project types in order to meet the demand from multiple, diverse stakeholders to participate in the KOICA peace and governance program.

Finally, an approach to connect the method of Korea's delivery of democracy aid and loan-type aid should also be sought. This is because when it comes to building infrastructure to improve democratic systems and institutions, it is more important to mobilize loan-type aid methods to provide infrastructure services such as media centers or broadcasting station systems than grant-type aid centered on technical cooperation and knowledge sharing. However, Korea’s democracy aid is still in the early stages, and the conceptual discussions and demands for institutional efforts to connect loan-type aid with Korea’s democracy experience have not yet begun.

IV. Limitations and Response Strategy: Agenda for South Korean Democracy Aid

The sharing of Korea's experiences with democracy with developing countries to support their democratization, help encourage the consolidation of a healthy democracy, and efforts to revise the content and delivery method of foreign aid provide important meaning to both Korea as a donor country and its partner recipient countries. It is important to understand the following current limitations and seek ways to respond to these limitations to systematize and fully construct the story of Korea’s democracy aid in the future.

First, it is necessary to reorganize the domestic system and create a knowledge network to share Korea’s experiences of democracy through public-private cooperation. It is highly likely that organizations related to development cooperation in Korea are still not familiar with the concept of democracy aid. Instead, they use similar individual concepts and focus on areas such as peace, human rights, gender, refugees, civil society, and governance rather than democracy as a whole. There is no need to go overboard and intentionally integrate all of these efforts, but it will be important to cooperate and exchange information on various democracy aid-related projects to establish a loose type of knowledge network and avoid overlapping areas and projects. In addition to government-civil society public-private partnerships, it will be important to link academic research and organizations to the knowledge network platform so that they can assist in the work of organizing the narrative of Korea’s democracy aid experience. If a basic foundation is established so that various stakeholders can participate in the democratic knowledge network, it will create an effective space in which a variety of voices and approaches are reflected.

Second, it is necessary to find aid strategies to support democratic governance at the pan-government level. Rather than trying to establish Korean-style democracy aid as a model, which runs the risk of appearing to be an aid condition for developing countries, efforts should be made to improve the support system so that democratic governance that encompasses individual freedom, human rights, protection for minority rights, and rule of law can be established within the historical and political context of the recipient countries. This consolidation of democratic governance is expected to have a more practical socioeconomic aid effect by improving the resilience of recipient countries to overcome the internal and external crises that they frequently face. Korea's development aid has thus far shown public administration and institutional improvement to be its strengths. However, efforts must be made to systematically overhaul the existing Korean development aid model by connecting it with the universal language of development cooperation of establishing effective democratic governance and further expanding the content and modules of the country’s democracy aid. To this end, a system that controls the political sensitivity of democracy aid and first identifies what the demand of recipient countries is and reflects it in project design and democracy aid strategies should be established.

Third, in order to sustainably institutionalize Korea’s contributions to the development of global democracy, it is necessary to clarify the relevant laws through legislation. Korea is already contributing to the development of democratic governance in the international community through a variety of projects and programs, although the name democracy is not used. This is why it is important to institutionalize these contributions in a more systematic, integrated, and effective manner. Such legislative efforts can systematically support the democratic development and resilience of developing countries and will help increase the amount of financial resources on an institutional level within the legal framework compared to the current situation, where the entities running projects are fragmented and have to secure their budgets individually. Legislative activities on Korean democracy aid can contribute to planning and implementing projects that reflect more professional and in-depth considerations of democracy as compared to current projects, and can also contribute to the development of domestic democracy capabilities by demonstrating the effects of introspection and education on democracy to domestic groups participating in democracy aid projects as well as to recipient countries. Specifically, "democracy promotion" can be added to paragraph 1 of the Framework Act on International Development Cooperation, and specific implementation measures can be stipulated in subordinate statutes such as the "Basic Plan for International Development Cooperation” or “Comprehensive International Development Cooperation Implementation Plan.” It is also possible to implement specialized democracy support projects by enacting laws to establish funds or foundations related to democracy support.

Fourth, aside from enacting laws related to democracy support, it is possible to create a liberal democracy fund with some degree of financial support so that various organizations can seek democracy aid. As discussed earlier, democracy aid-related organizations besides KOICA are engaging in projects with very small budgets that are not sustainable in the long term. While it is important to increase the government budget, it will also be important to simultaneously seek ways to create and autonomously manage private funds so that such organizations do not have to rely solely on the government for funding. Korea does not yet have a foundation that shares Korea's democratization experience with developing countries and supports democracy in developing countries. The ASEAN Human Rights Fund Act was recently proposed in the National Assembly in May 2021, but legislative efforts are needed to support democracy in developing countries globally without regional, organizational, or funding restrictions.

Fifth, it is necessary to expand the channels that can strengthen the involvement of local civil society in order to support the democratic governance of intended partner countries. Since recipient country governments are unlikely to ask Korea to improve its politically sensitive democracy-related institutions, civil society needs state support to expand the capacity and opportunities to engage in institutional improvement and raise issues related to democratic governance. Civil society organizations in recipient countries can publicize various issues in democratic governance areas such as anti-corruption, freedom of the press, and human rights advocacy more directly than the government. Civil society groups from developing countries can cooperate with local groups through a Korean CSO alliance or they request support for democratic governance improvement from the Korean government directly.

Sixth, there is a data problem. Since the methods and entities by which Korea's democratic experience is disseminated are diverse and fragmented, relevant statistical data is not systematically linked. It is an urgent task to unify the statistical data between institutions, and the knowledge network platform mentioned above will be able to take on the role of managing statistical data and documents for smooth communication.

Seventh, in order to formulate the experience of Korean democracy aid into a single narrative, it will be important to institutionalize the unique expertise and experience of each aid organization into a knowledge-sharing program and lay the foundation for continuing to accumulate such knowledge in the future. This KSP will make it possible to offer developing countries assistance in improving democratic institutions in the manner they request through support for development consulting on issues such as human-rights based approaches, responses to gender issues, and so on. The current KSP project being promoted by the Ministry of Economy and Finance and KDI is centered on Korea's economic development experience, so there is clearly a limit to the inclusion of Korean democracy and political and social development experiences. The most realistic way forward at the moment would be to use the Development Experience Exchange Partnership Program (DEEP), a development consulting project run by KOICA.

Eighth, efforts should be made to expand partnerships so that a variety of actors can participate in development cooperation projects which share Korea’s democracy experience. Knowledge-sharing does not have to be limited to civil society associations. It can be expanded to support the improvement of the parliamentary system through participation in the National Assembly, fundraising through private companies, and fostering private companies in developing countries.

Ninth, it will be important to emphasize that Korea’s cooperation with developing countries to share its democracy experience is not intended to convey the uniqueness of Korea’s experience, but rather is intended to convey the connection that Korea’s democracy experience has to universal democratic values shared by the international community. It is important to seek to strengthen multi-layered cooperation centered on the core values of SDG16, and to make an effort to emphasize that the strategies and implementation focus of SDG16 are within the same context as Korea's democracy aid projects. In addition, efforts should be made to ensure that human rights-based approaches, environmental, and social, and human rights impact assessments, and the principle of accountability are embedded in the planning and implementation of Korean democracy aid. This will allow the more active pursuit of multilateral cooperation methods with international organizations (multi-bi aid, trusts, and so on).

Finally, Korea's democracy experience and aid have implications at the macroscopic level as a global narrative, and offer an important rudder to steer Korea’s democracy forward. Currently in East Asia, the realist national interest-oriented politics of great powers such as the United States, China, Japan, and Russia are sharply opposed, and discussions on peace and democratic governance are easily derailed as they seek the protection of their own national interests on issues such as North Korea’s nuclear weapons, territorial disputes, and historical disagreements. It is time for Korea to harness its historical experience of democratic governance to play the role of “Northern Europe of East Asia,” and democracy aid should be used as a soft power asset so that Korea can be recognized as a symbol of peace and democracy in East Asia.

[1] Thomas Carothers, Aiding Democracy Abroad: The Learning Curve (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1999), p, 88.

[2] KOICA Statistics on Grant-based Aid (2016-2019)

[3] KOICA Statistics on Grant-based Aid (2016-2019)

[4] KOICA Statistics on Grant-based Aid (2016-2019)

■ Taekyoon Kim is a professor of International Development and an associate dean for academic affairs at the Graduate School of International Studies at Seoul National University. He currently serves as an executive director of the Korea International Cooperation Agency and a member of the Sustainable Development Committee for the city of Seoul. He also served as a visiting professor at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, USA, Lingnan University, Hong Kong and Tübingen University, Germany. His recent publications include "Tax Reform, Tax Compliance and State-Building in Tanzania and Uganda," Africa Development 43(2), 2018 (co-authored), and "Social Politics of Welfare Reform in Korea and Japan: A New Way of Mobilizing Power Resources," Voluntas 30(2), 2019 (co-authored). He received his Ph.D. in international relations from Johns Hopkins University-SAIS and D.Phil. in social policy and intervention from the University of Oxford.

■ Typeset by Ha Eun Yoon Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | hyoon@eai.or.kr

Center for Democracy Cooperation

South Korea Democracy Storytelling