![[EAI Issue Briefing] Myanmar Citizens Legitimized the 2020 General Election: The Post-Election Surveys Denying the Military Claims](../images/bg_tmp.jpg)

[EAI Issue Briefing] Myanmar Citizens Legitimized the 2020 General Election: The Post-Election Surveys Denying the Military Claims

Commentary·Issue Briefing | 2021-02-10

Jin Seok Bae, Sook Jong Lee

[Editor’s Note]

The military seized control of Myanmar on February 1, following the November 2020 general election which resulted in huge victory for Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) party. The military claims that the election was a “fraud,” demanding a rerun of the votes. The Union Election Commission and local and international observers have denied such charges, stating that there have not been previously arranged election manipulations. In response to these events, Professor Jin Seok Bae and Professor Sook Jong Lee raise an important question: How do citizens of Myanmar perceive the recent election and the state of democracy in their nation? The authors analyze results of post-election surveys conducted by the East Asia Institute(EAI) and its local partnership institutions in Mandalay Region and Kachin State. While these surveys do not represent the nationwide opinions, the authors contend, they show the majority of citizens believe the election was free and fair and support the democratization their nation. The authors add that in order for Myanmar to progress beyond the current situation, there needs to be support for Myanmar democracy from the international community including Asian democracies.

Introduction

On February 1, 2021, the Myanmar military declared a state of emergency, detaining the president and key members of the ruling party, the National League for Democracy (NLD). The cause of the emergency declaration was alleged "election fraud." On February 8, the military imposed martial law and banned gatherings of more than 5 people, first in Mandalay and Yangon and then in other parts of the country as protest rallies arose. The imposition of these rules came with a warning that curfew violators would be shot.[1] The military asserted that there was terrible fraud in the voter list and that this problem will obstruct the path to democracy. Two months earlier, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), the military’s electoral proxy, argued immediately after the election that the voting process had been damaged by fraud. To bolster the USDP's claims, the military raised suspicions of widespread inconsistencies in voter lists and announced on January 26 that 8.6 million cases of fraud were confirmed.

In fact, the Union Election Commission and local and international observers have repeatedly rejected this election fraud charge.[2] Multiple local election monitoring organizations endorsed the legitimacy of the election.[3] International observers also concluded that some deficiencies were not significant enough to affect the election results and there were no large-scale, intentional election manipulations.[4]

The real question is how the citizens of Myanmar think about their democracy and the election. The East Asia Institute (EAI), together with its Myanmar partner institutions, conducted a post-election survey related to the 2020 general election in Myanmar during December 2020 to investigate the voting behavior and political opinion of Myanmar citizens. Due to COVID-19, the original plan to conduct a nationwide poll was reduced to two polls in Mandalay Region and Kachin State respectively. The post-election surveys on the 2020 general election were conducted through face-to-face interviews using a structured questionnaire. Interviews were held from December 12th to 27th in Mandalay Region, and from December 7th to 22nd in Kachin State, with a sample size of 400 and 758 adults (aged 18 years and older), respectively. Accordingly, the survey data used here is not representative of the opinions of all Myanmar citizens. Nevertheless, the data from these two areas is valuable for understanding public opinion, as each area has important demographic and political characteristics.

The political influence of the ruling NLD is quite strong in Mandalay Region. In this 2020 general election, the NLD took 35 out of 36 seats in the House of Representatives, and the other seat was won by the USDP. Mandalay’s ethnic makeup is primarily composed of Bamar, the majority ethnic group in Myanmar. Mandalay Region provides a reasonable picture of public opinion across Myanmar, where the NLD has shown overall political dominance. In Kachin State, on the other hand, the political influence of the ruling NLD remains relatively weak. In this general election, the NLD took 13 out of 18 seats in the House of Representatives, with 4 seats won by the USDP and the remaining seat taken by the Kachin State People's Party (KSPP). Kachin State is the second most influential area of opposition supporters in Myanmar after Shan State. Due to the past decade of civil war and the resulting issues of internally displaced people, the NLD government treats this state as politically sensitive. Kachin State is also very diverse in terms of ethnicity compared to other states and regions. In this regard, Kachin provides a general picture of the opinion of the section of the public who opposes the NLD.

Voters Strongly View the Election as Free and Fair

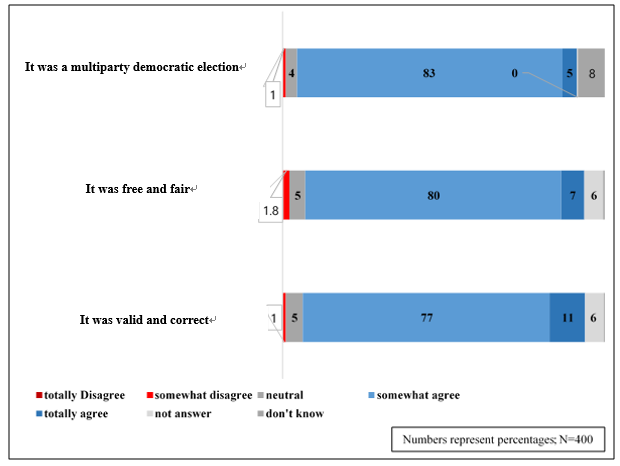

Our first concern is the perception of Myanmar citizens about the fairness of the last general election. First, we look at the results of the Mandalay Region survey. As shown in Figure 1, a vast majority of the survey respondents somewhat agreed (82.5%) or totally agreed (4%) with the statement that the “2020 General Election is a multiparty democratic election.” Similarly, 86.7% of respondents agreed with the statement that the “2020 General Election was free and fair.” Around 88% of respondents agreed with the opinion that the “2020 General Election was valid and correct.” Only about 1% of respondents answered these questions negatively.

Figure 1. Opinion on the 2020 General Election in Mandalay Region

Source: Post-election Survey in Mandalay Region (2020)

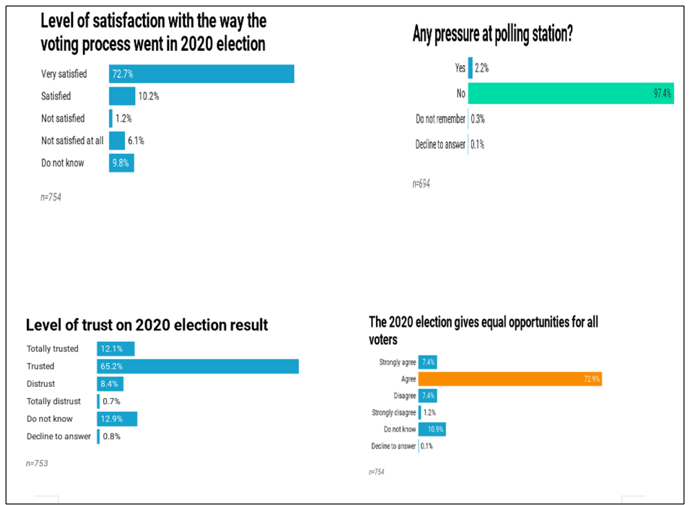

In the Kachin State survey, there were no questions that directly addressed the fairness of the election. However, there were similar queries, such as whether the respondents trust the election results or if they are satisfied with the election process. As shown in Figure 2, a vast majority of respondents were very satisfied (72.7%) or satisfied (10.2%) with the way the voting process went in the 2020 election. Almost all (97.4%) reported experiencing no pressure at the polling station. Similarly, 77.3% of respondents overall trusted the 2020 election results, while only 9.1% of respondents expressed distrust. Around 80% of respondents agreed with the statement that the “2020 general election gave equal opportunities for all voters.” Only 8.6% of respondents disagreed with this statement.

Figure 2. Opinion on the 2020 General Election in Kachin State

Source: Post-election Survey in Kachin State (2020)

The ethnic party, the KSPP, and the pro-military party, the USDP, are relatively strong in Kachin State. In this general election, these parties also ranked second and third respectively in Kachin State. One major concern is whether respondents who supported these parties trust the election results. In our survey, 68.3% of the respondents who voted for the USDP and 63% of the respondents who voted for the KSPP stated that they trust the election results. Among the major opposition supporters, only 23.8% (USDP) and 17.9% (KSPP) said they did not trust the election results. Contrary to the military's argument, we found that relatively fewer opposition supporters did not trust the election results.

Strong Support for the Democratization of Myanmar

Our second concern is the opinion of Myanmar citizens regarding the political situation leading up to the NLD's landslide victory in the 2020 general election. By gauging the response to the question of whether Myanmar is headed in the right direction, it may be possible to deduce the legitimacy of the emergency declared by the military. Very few of the respondents in the two areas surveyed said that Myanmar is headed in the wrong direction. The vast majority of respondents (85%) in Mandalay Region thought that the country is headed in the right direction as opposed to a tiny minority (2%) who thought that the country is going in the wrong direction. In Kachin State, a high percentage of respondents replied "I don't know" to this question (41.9%), but only 12.1% said that Myanmar is moving in the wrong direction, while 44.3% said it is going in the right direction.

We can attest that the cause of the Myanmar military's emergency declaration is at odds with public opinion in Myanmar. The vast majority of Myanmar citizens have recognized the legitimacy of the 2020 general election. Those surveyed also generally felt that Myanmar is headed in the proper direction of democratization. Nowhere in this poll was there an indication that Myanmar was in sufficient crisis to declare a state of emergency. We need not hesitate to assert that the military's declaration of emergency is clearly a coup.

The Military’s Limited Options after the Coup

Despite the strong support for further democratization of their country, many people in Myanmar did not have high expectations regarding the military's political role. In the Mandalay Region survey, when respondents were asked about the things that they expect to materialize under the newly elected government, only 28% of them agreed that the military’s involvement in politics will decline. Although 65% of respondents agreed that democratic values will strengthen and 52% predicted an increase in freedom of speech, relatively fewer respondents predicted that the military's influence might decrease.

The power sharing agreement that the country has run under for the past decade has created a certain acceptance of the Myanmar style of gradual or partial democratic transition. However, many citizens expressed concern that such a system clearly limited the potential scope of democratic reform, making it difficult to recognize real progress in democratization.

The NLD has contributed to the democratic transition in Myanmar, but the transition remained limited owing to the solidarity of the military as an opposition force. The NLD failed to divide the military and create any substantial faction which was on its side, and as such could not create a parallel force as a counterweight to the regular forces. The country’s democratic leaders did not have the power to rotate command positions or to timely purge rival military officers.[5] Just as Huntington[6] feared, the democratic government of Myanmar “spoiled” the military by providing it with additional material, financial, and political resources rather than weakening its ability to wield power in parallel. This spoiling increased the ability of the military to organize a successful coup.[7] Myanmar’s democratic political leaders found themselves in a trap. No meaningful actions that might reduce the military’s ability to successfully regain power could be taken, because such actions in themselves were likely to spark a coup. This is why the NLD government was helpless when the military threatened a coup in late January. Myanmar’s fledgling democratic arrangement, which was dubbed “a pacted transition,” is clearly not tenable in the long run.

The Myanmar military also cannot be optimistic about the situation. It has declared a state of emergency and promised new elections in a year, but it is very unlikely that the military will take office in a new election. Post-coup elections are often regarded as a referendum on the coup. As the poll results show, the citizens of Myanmar are assigning legitimacy to the 2020 general election results. If elections are held again, the defeat of the military will be very likely. The military will not be able to postpone the promised new election since it is difficult for an authoritarian regime to legitimize their continuous post-coup control of government. Research shows the median duration of coup-born regimes that held elections was approximately 88 months (7.3 years), while coup regimes that did not hold elections lasted only 24 months.[8] The Myanmar military’s options after the coup appear to be quite limited.

According to the survey results in Kachin State, about 70% of the respondents agree with the statement that international organizations should have the opportunity to effectively pressure Myanmar regarding its human rights abuses, and only a small parentage (9.1%) believe that international organizations should not be allowed to pressure Myanmar. The same mindset can be applied to the coup. Like the human rights issue, there seems to be support within much of Myanmar for the international community to apply pressure with regard to the military takeover. Leaders from the UN, the Biden administration, and other Western democracies have denounced this unfortunate putsch by the military. It is time for Asian leaders to join in and raise their voices to show their support for Myanmar’s democracy. ■

[1] Al Jazeera and News Agencies. 2021. “Myanmar military ruler defends coup as protests intensify.”https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/2/8/myanmar-military-leader-gives-first-address-to-nation-since-coup

[2] Pyae Sone Win. January 29, 2021. “Myanmar election commission rejects military’s fraud claims.” apnews.com.

[3] Domestic Election Observer Organization. 2021. “Joint Statement by Domestic Election Observer Organization.” https://www.pacemyanmar.org/mmobservers-statement-eng/

[4] The Carter Center. 2020. “Election Observation Mission: Myanmar, General Election, November 8, 2020.” https://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/news/peace_publications/election_reports/myanmar-preliminary-statement-112020.pdf

[5] Biddle, Stephen and Robert Zirkle. 1996. “Technology, Civil-Military Relations, and Warfare in the Developing World.” Journal of Strategic Studies 19(2): 171-212; Sudduth, Jun Koga. 2017. “Coup Risk, Coup-Proofing and Leader Survival.” Journal of Peace Research. 54(1): 3-15

[6] Huntington, Samuel P. 1991. The Third Wave. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press

[7] Feaver, Peter. 1999. “Civil-Military Relations.” Annual Review of Political Science. 2(1): 211-241

[8] Grewal, Sharan and Yasser Kureshi. 2019. “How to Sell a Coup: Election as Coup Legitimation.” Journal of Conflict Resolution. 63(4): 1001-1031

■ Jin Seok Bae is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Gyeongsang National University in South Korea. His primary research interests lie in elections, party politics, and public opinion in the context of democratization and new democracies. He participated as a practitioner in the founding of Asia Democracy Network and Asia Democracy Research Network in 2013 when he was a Research Fellow at the East Asia Institute.

■ Sook Jong Lee is a Senior Fellow and Trustee at the East Asia Institute and served the Institute as President from 2008 to 2018. She is also a professor of public administration at Sungkyunkwan University. Her recent publications include Transforming Global Governance with Middle Power Diplomacy: South Korea’s Role in the 21st Century (ed. 2016), Keys to Successful Presidency in South Korea (ed. 2013 and 2016), Public Diplomacy and Soft Power in East Asia (eds. 2011).

■ For inquiries: Juhyun Jun, Research Associate/Project Manager

02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) I jhjun@eai.or.kr