[Asia Democracy Issue Briefing] South Korean National Pride beyond "Patriotism Highs" and "Hell Chosun"

Commentary·Issue Briefing | 2020-10-29

Hanwool Jeong

Editor's Notes

The “Patriotism Highs” controversy and the “Hell Chosun” discourse have been pervasive in Korean society, reflecting Koreans’ perspective towards their society today. In this issue briefing, Dr. Hanwool Jeong, Senior Research Fellow at Hankook Research, analyzes the reasons behind the sharp rise in national identification and national pride among Koreans based on the results of the Korean Identity Survey conducted in 2020. Dr. Jeong said that the remarkable increase in national pride has resulted from the successes of the response to COVID-19 acclaimed as “K-quarantine” as well as the reappraisal on the Korea’s health/welfare system along with civic awareness. At the same time, Dr. Jeong points out that we should be vigilant of the so-called “patriotism highs (guk-ppong)”, raising the need to address the fundamental problems plagued in our society and also the importance of restoring pride and trust in our communities first.

The Success of K-Quarantine and the “Patriotism Highs” Controversy

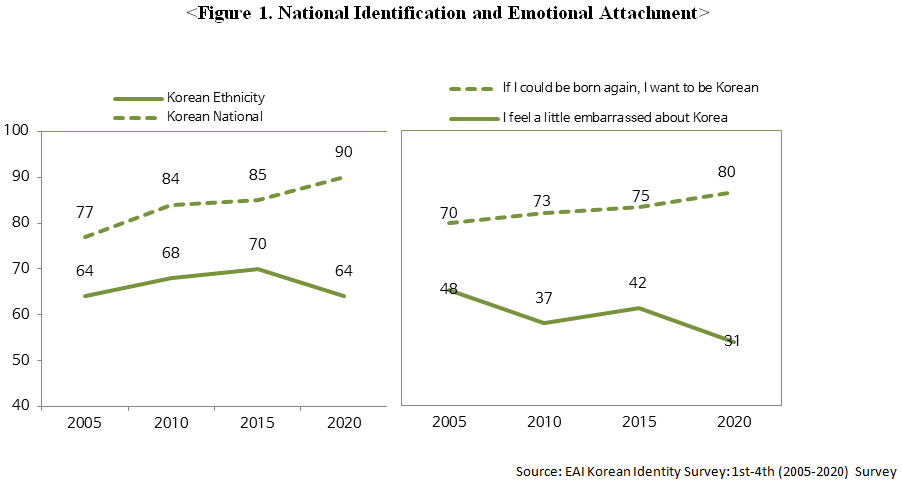

In the 2020 round of the Korean Identity Survey, a quinquennial survey launched in 2005 conducted jointly by the East Asia Institute (EAI) and the East Asia Collaboration Center (EACC) at Sungkyunkwan University, a remarkable increase was noted in the degree of national identification and national pride expressed by survey participants. In the first round of this survey conducted in 2005, 77% of respondents indicated that they felt a sense of community as a Korean national. This figure has climbed steadily over time to reach 90% in 2020. This result is in contrast to the percentage of those who said they felt an affinity with an ethnic Korean, which increased slightly and then declined to 64%.[1] Further, in place of the previous trends that had exhibited national pride and embarrassment concurrently, a sense of positive psychological attachment to national pride is strengthening. In 2005, 70% of survey respondents agreed with the statement “If I could be born again, I would want to be Korean,” while in 2020, that figure jumped to 80%. While 48% of respondents agreed with the statement “I feel a little embarrassed about Korea” in 2005, just 31% said the same in 2020, which is a huge drop.

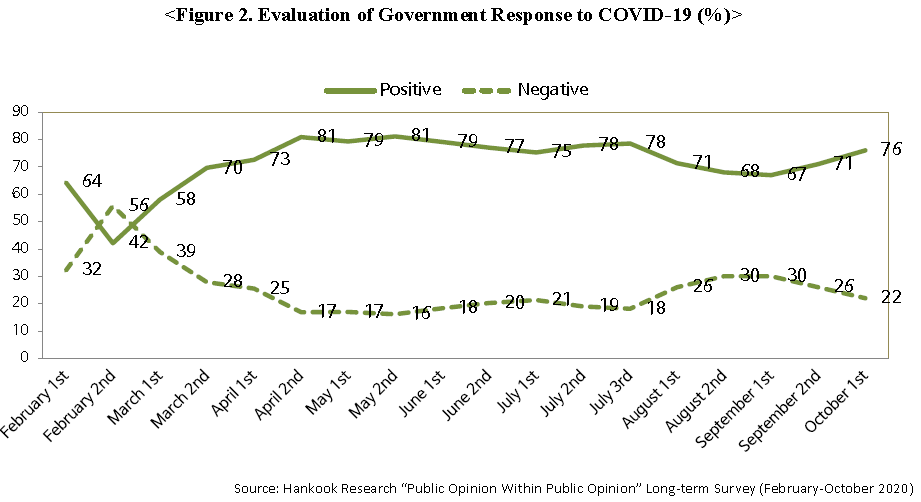

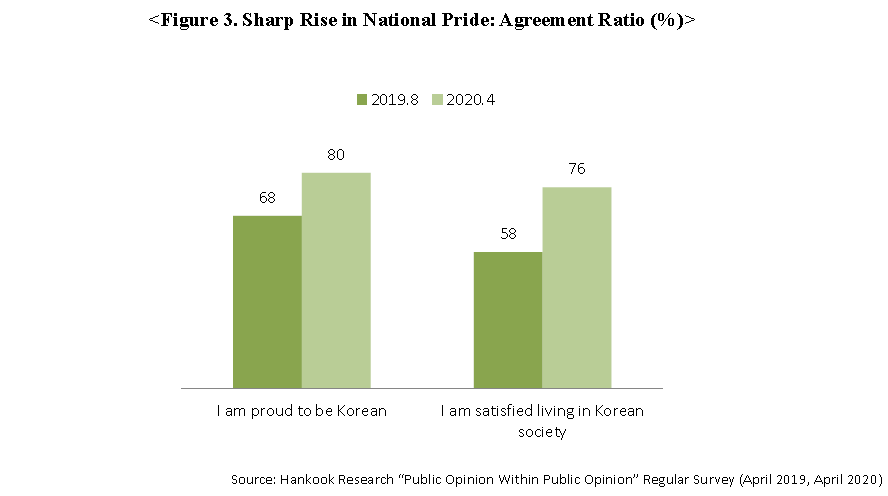

The increasing sense of national pride and unity felt among Koreans is in part due to the international attention that the country’s success in containing COVID-19 has drawn. According to the results of Hankook Research’s biweekly regular survey “Public Opinion Within Public Opinion,” following the two weeks in March when South Korea’s cases dropped rapidly, 70-80% of the public has consistently rated the government response to the coronavirus highly. While this figure fell to 50% after cases increased again following August 15 2020, it climbed back up to 75% when the government lowered the social distancing level to 1 during the first week of October (see Figure 2). Koreans began to use the shortened term “K-quarantine” to refer to their government’s success in combating the coronavirus, as they heard about the widespread reporting in outlets like The Wall Street Journal and CNN on Korea’s declining cases, contact tracing app, and diagnostic kits.[2] In the Public Opinion Within Public Opinion survey conducted in August 2019, which was the pre-coronavirus period, 68% of respondents agreed with the statement “I am proud to be a Korean,” but by April 2020 that figure had jumped to 80%. In the same survey, the number of respondents who agreed with the statement “I am satisfied living in Korean society” went from 58% to an astonishing 76% during the same time frame (Figure 3). There is a growing concern over the so-called excessive “patriotism high” vis-a-vis the tangible feeling of national pride in Korean society right after K-quarantine has yielded success, which is considered the defining moment that has resulted in the strengthened national pride. There have particularly been an increasing number of discussions about the phenomenon of the “patriotism high” among those in their 20s and 30s.[3]

Of course we can also attribute this debate over “patriotism highs” and increasing national pride to the factors such as BTS reaching No. 1 on the Billboard Chart against the backdrop of the ongoing K-pop and K-drama craze and Bong Joon-ho’s film “Parasite” winning the Academy Award this year. Besides, the government-led implementation of K-quarantine in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic (especially the leadership of the health authorities) and the strengths of Korea’s welfare and healthcare systems have been considered another contributing factors. According to a survey conducted jointly by KBS, Sisain, Seoul National University, and Hankook Research, an astounding 53% of survey respondents stated that their trust in the country had increased, and 27% said their trust in the Blue House[4] had increased, while 21% said their trust in the government as a whole had increased, following the outbreak of COVID-19. If we consider that in contrast, trust in religious institutions (-46%), the media (-45%), and the National Assembly (-33%) among many others experienced a drastic decrease, it is difficult to deny the influence of K-quarantine on the recent increase in national pride.[5]

Factors for Increasing National Pride: Rediscovery of “K-Healthcare/Welfare” + “K-Citizens”

Looking at the existing debates, it is pointed out that the magnifications of the successes of the government’s K-quarantine combined with media and YouTube content enumerating the failures of foreign governments and exaggerating Korea’s superiority are inflaming the feelings of patriotism intoxication among Koreans, particularly among youths. In other words, there is a growing concern that this tendency has led to an overly positive assessment of Korea and a denigration of other cultures.

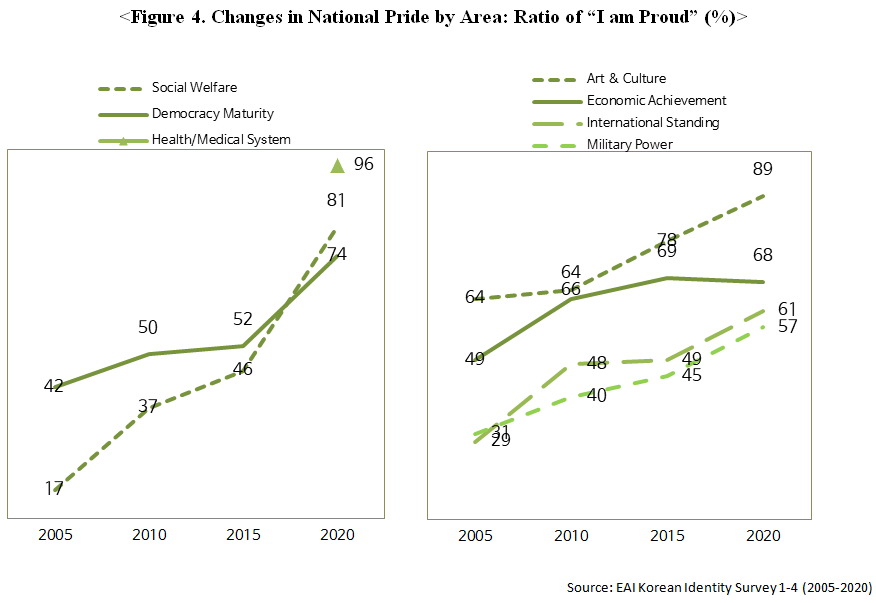

However, looking at the results of the Korean Identity Survey 2020, the impact of COVID-19 has not been limited to increase in national pride and feelings of superiority about Korea compared to other countries. There has also been a major reappraisal of the formerly unrecognized strengths of Korea’s healthcare/welfare system, along with the citizens’ patient adherence to and implementation of the prevention guidelines. Looking at Figure 4, other categories related to Korea’s sharp rise in national pride increased dramatically compared to the 3rd survey conducted in 2015. There was a 35% (46%→81%) increase in the number of respondents who were proud of the level of Korea’s social security support and a 22% (52%→74%) increase in those who were proud of the maturity of Korea’s democracy. The 2020 survey included “healthcare/welfare system” for the first time in this question category, and a whopping 96% of respondents agreed that they were proud of Korea’s system.

In the 2020 survey, 89% of respondents felt pride in Korea’s “culture and arts”, represented mainly by Hallyu (K-pop and K-dramas), following “Korea’s national healthcare system”, contributing significantly to the overall increase in national pride. However, “culture and arts” only marks an increase of 12% (78%→89%) compared to the result five years ago. Compared to the 22% rise in this category between 2010 and 2015, the trend appears to be falling. There was no change in how Koreans felt about the country’s “economic achievements” compared to the 2015’s survey, while “military power” saw a 12% (45%→57%) increase, as did “Korea’s international standing” (49%→61%).

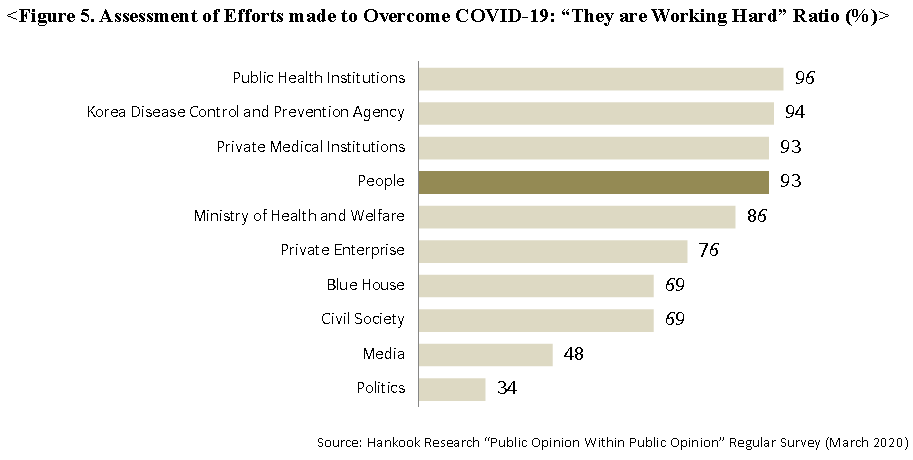

Korea’s national healthcare system, democratic maturity, and the level of social security were previously something of a target for social ridicule. The rapid increase in national pride regarding these categories is, again, difficult to explain without factoring in the variable of the country’s response to COVID-19 outbreak. Looking at the March results of Hankook Research’s “Public Opinion Within Public Opinion” survey, when asked about the principal agents within society that have made the greatest effort to overcome COVID-19, respondents ranked “public health institutions” (96%) followed by “the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA)” (94%) and “private medical institutions” (93%). More than 90% also selected “the people.” Respondents were also amicable towards the efforts made by the government as seen in the Ministry of Health and Welfare (86%) and the Blue House (69%).

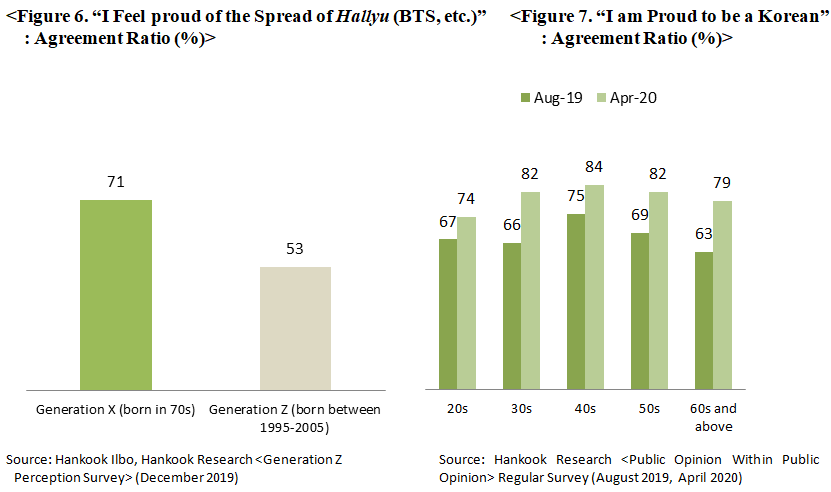

The sensitivity of the “national pride” response is in fact closely mirrored among those who are middle-aged and older, rather than the younger generations. According to a comparative research survey titled “Generation Z and Generation X (those born in the 70s)” conducted by Hankook Ilbo and Hankook Research in January 2020, the level of national pride felt among Korea’s youth does not rise to that of the level felt by the older generations. While 71% of Generation X respondents agreed with the statement “I feel proud about the spread of Hallyu such as BTS,” just 53% of Generation Z respondents felt the same.[6] In comparison to the August 2019 “Public Opinion Within Public Opinion” survey, the greatest increase of agreement with the statement “I am proud to be a Korean” was 16% (66%→82%) among those in their 30s and those in their 60s (63%→79%). In contrast, agreement among respondents in their 50s increased by 13% (69%→82%), while 9% more of those in their 40s agreed (75%→84%) and just 7% more of those in their 20s agreed (67%→74%) with the statement. This survey results show that we must exercise caution and not assume that the opinions expressed by younger people online are shared by their entire generation.

Despite the Increase in National Pride, the Perception of “Hell Chosun[7]” Persists

One consideration of the marked increase in national pride is the potential for it to prohibit objective self-assessment and transform it into exclusive supremacy. However, in Korean society, the strengthening of national identification has been accompanied by liberal citizenship, rather than a suppression of liberal citizenship, and this positive function of national pride should not be overlooked. Pride is a factor that connects community members, and as such plays the role of the psychological glue that maintains community standards and shared interests. Further, increased pride in one’s community increases both individual trust in that community and the recognition of one’s social responsibility as a member of the community

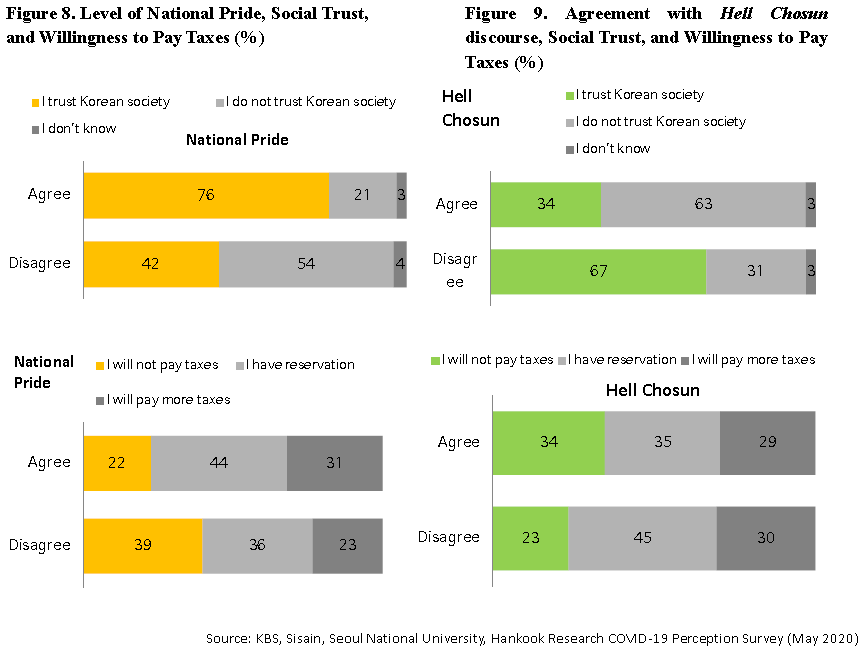

At the same time, we must not let our guard down when it comes to the harmful effect of the reverse bias “Hell Chosun” discourse. Weak trust capital is the biggest roadblock for Korea on the path to social maturity and growth. Establishing fair rule of law, social networks, a social safety net, and so on have been considered the building blocks to form trust capital [8] Of particular note is that according to the results of the recent survey, psychological attachment to a community can also have a significant effect on the development of social trust between members of that community. At the same time, we must also pay attention to the important role that cynicism and frustration toward a national community play in chipping away at trust capital. In fact, the survey conducted in May of this year by KBS, Sisain, Seoul National University, and Hankook Research confirmed that there is a clear correlation between social trust and national pride. Among those respondents who had strong national pride, 76% agreed with the statement “I trust Korean society,” while just 42% of respondents who indicated weak national pride did so. Further, pride in one’s community can enhance social responsibility and a sense of solidarity with disadvantaged community members. In the same survey, the group with strong national pride also indicated a high level of agreement with the statement “I will pay higher taxes to help the poor,” and a low level of agreement with the statement “I will not pay taxes.”(Figure 8 & 9). This plainly shows that a positive mindset gives rise to positive actions.

Korean Society’s Lack of Trust in Korean Law and Institutions, and the Absence of a Community Mentality

It is true that the government’s prevention response and leadership during COVID-19 have allowed us to feel our institutional strengths. However, the underlying recognition within Korean society of the weaknesses of the existing laws and institutions has not changed.

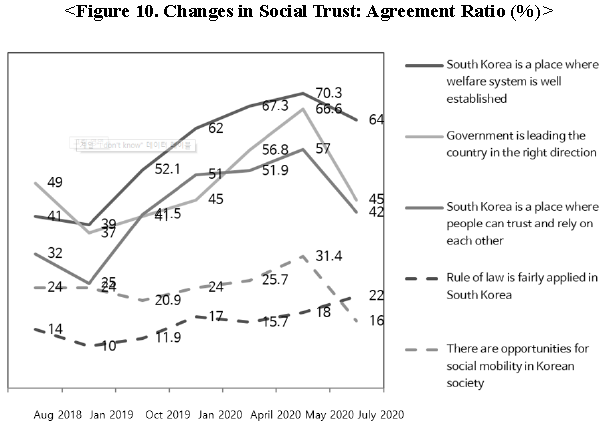

As you can see in Figure 10, during the response to COVID-19, trust in the government, social trust, and appreciation for the social welfare system sharply increased. While these changes have inspired optimism, distrust in the rule of law and the fundamental of society has remained steady during this time, and there seems no hope for opportunities for social mobility. Trust in the statement “The law is applied fairly in our society” is stuck at 20%, and just one or two people in ten agree with the statement “there are opportunities for social mobility.” These are the basic principles upon which society rests that offer a basis for hope. Without change to these fundamentals of society, the recent trust in the government and society that has arisen from pride in Korea’s coronavirus response is already showing signs of dropping in the changing environment.

Trust in the social welfare system remains steady, but the trend has stopped its upward trajectory (Figure 10). The debate in political circles about universal vs. selective welfare is hot, but beyond disease prevention, the social safety net is extremely weak. The percentage of citizens who can receive financial help from an institution when they are in need or help with household tasks when self-quarantining is just 30%. The percentage of citizens who said they can get help from a personal rather than institutional source does not reach 50%. According to a recent survey, the implementation of the flexible working system to deal with the situation has actually hit those who are already struggling with care burdens with a double whammy. Parents have emphatically had a negative response to flextime.[9]

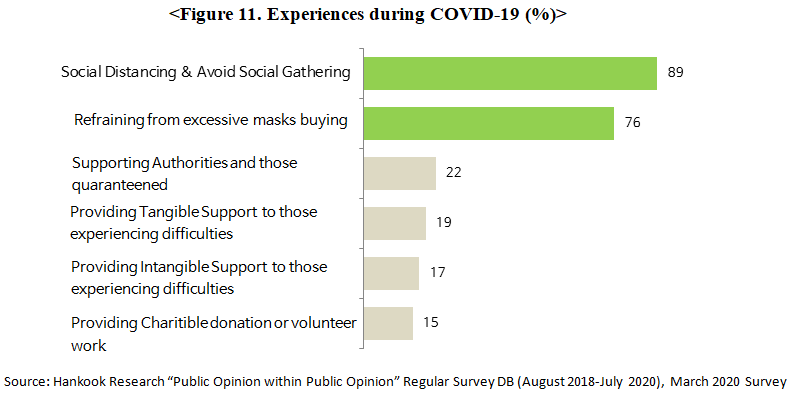

The pride of the people themselves, who are of course the main players in terms of pride in Korean democracy, also rests on this vulnerable foundation. The Korean public has been phenomenal in terms of voluntarily restraining their rights and freedoms by social distancing and enduring the mask crisis under the goal of disease control. However, civic action has also failed to advance to the stage of taking the additional step needed to prevent problems before they arise. The percentage of people who have given either tangible or intangible support to those experiencing difficulties balancing care obligations and financial hardship is less than 20%, and just 15% of respondents indicated they had ever made a charitable donation or participated in volunteer work (Figure 11). In other words, there is no social safety net in place to help those disadvantaged members of society who are either outside the scope of the government’s assistance or who fall through the cracks of the existing system. The government needs to expand the social welfare system, but these results also show that there is a need for a more advanced citizenship in terms of solidarity and social responsibility.[10]

[1] Kang Won Taek discussed the dual phenomenon of increasing national identity and decreasing ethnic identity and the reasons behind it using the same survey. See “Korea’s National and Ethnic Identity: Fifteen Years of Change” (EAI Working Paper) 2020.

[2] “The World Focuses on K-prevention...Government, Press Briefings Held” Yonhap News (2020.05.07)

[3] The Korean word “Guk-ppong” translated here as “patriotism high” (or “patriotism intoxication”) is a compound word composed of “nation” and “philopon,” the name for methamphetamine coined by the Japanese and imported into Korea. It is used to describe a state of being high or intoxicated with a feeling of excessive national pride. “Head of National Diplomatic Academy Warns Against Patriotism High over K-prevention...Don’t Get Carried Away with Expectations, Arrogance” (2020.05.28); Weekly Chosun, “COVID-19 is Raising Youths to Be Patriotism High Addicts” (2020.06.18); Kyunghyang Shinmun, “The Patriotism High of K-prevention” (2020.06.29); Hankook Ilbo, “Why 20-30 Year Olds Are Still Clamoring to Leave Korea Despite Being High on Patriotism” (2020.09.16)

[4] Blue House refers to the Korean presidential residence

[5] Cheon Kwan Yool. “The ‘Korean World’ Emerging from COVID-19 - An Unexpected Response” Sisain. Vol. 663 (2020.06.02)

[6] Hankook Ilbo. “Why Should I Live Like You?...Generation Z’s Lack of Support for Unification” (2020.01.03)

[7] Editor’s Note: Hell Chosun is a satirical South Korean term that became popular around 2015. The term is used to criticize the socioeconomic situation in South Korea. It is particularly popular among younger Koreans, due to their feelings about unemployment and working conditions in modern society https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hell_Joseon

[8] Lee Jae Yeol. If I Were Born Again I’d Still Be Korean: Searching for the Lost Dignity of a Society that Went From the Miracle on the Han to Hell Chosun. (21st Century Books, 2019).

[9] For details, see Choi Sun-ah. “Flextime Brought On By Coronavirus, Present and Future” Hankook Research, Public Opinion Within Public Opinion Vol. 101-01 (2020.10.28).

[10] Kim Hye-jin. “In the Midst of Overcoming COVID-19, Social Trust and Mutual Trust Thicken, but Half is Self-Sustaining” Hankook Research, Public Opinion Within Public Opinion Vol. 72 (2020.04.08).

[11] Translator’s note: The “N-po” generation is used to mean “numerous giving-up generation” or “the generation that gave up N amount of things.” The term is a derivation of and expansion on the Sampo generation which gave up three things: dating, marriage, and childbirth. The Opo generation gave up on five things: dating, marriage, childbirth, home, and career. “N-po” indicates a generation that has had to abandon all of these things plus hobbies, education, human relationships, etc., an “endless number of things,” due to soaring housing and tuition prices and increasingly scarce employment opportunities.

■ Hanwool Jeong is a Senior Research Fellow and Research Designer at Hankook Research in South Korea. He received his Ph.D. in political science from Korea University, and was the executive director at the Center for Public Opinion Research at the East Asia Institute until 2015. His recent publications include “The Corruption Scandal and Vote Switching in South Korea’s 19th Presidential Election” (2019), “Generation as Group Identity and its Political Effect” (2018), “Rising Swing Conservatives in South Korea: The Causes and Results” (2017) and “National Identity Change in South Korea: The Rise of Two Nations and Two State Identities” (2017).

■ Typeset by Eunji Lee, Research Associate/Project Manager

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 207) | ejlee@eai.or.kr

The East Asia Institute takes no institutional position on policy issues and has no affiliation with the Korean government. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in its publications are the sole responsibility of the author or authors.

Center for Democracy Cooperation

South Korea Democracy Storytelling

Democracy Cooperation