Japan and Geo-Economic Regionalism in Asia: The Rise of TPP and AIIB

Commentary·Issue Briefing | 2016-02-03

Terada Takashi

Terada Takashi is a professor of international relations, Doshisha University, Kyoto. He received his Ph.D. from Australian National University in 1999. Before taking up his current position in April 2012, he was an assistant professor at National University of Singapore (1999-2006) and associate and full professor at Waseda University (2006-2011). He also has served as a visiting fellow at University of Warwick, U.K. (2011 and 2012) His areas of specialty include international political economy in Asia and the Pacific, theoretical and empirical studies of Asian regionalism and regional integration, and Japanese politics and foreign policy. His articles were published by major international academic journals including The Pacific Review, Contemporary Politics, Australian Journal of International Affairs, Studio Diplomatica, and International Negotiation. He has completed his book project in Japanese entitled East Asia versus the Asia-Pacific: Competing Institutions and Ideas for Regional Integration (University of Tokyo Press, 2013).

Introduction

A current trend of the regional political economy of Asia is the strategic linkage between geo-politics and regional economic institutions, which can be labelled geo-economic regionalism. The upsurge in new economic regionalism in Asia and the Pacific, as evident in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), conceivably constitutes a major box of tools in US and Chinese struggles to form a new regional economic order in Asia. The United States and China have exploited these regional settings as valuable resources for imposing sets of norms and rules upon regional economic and security agendas. In doing so, the power struggles between the United States and China in Asia have primarily developed around standard-setting through institution-building, not any direct military arms race or trade friction talks, as a new way to dominate the regional order-creating processes. For instance, the launch of AIIB, as a key financial institution to bolster China’s “One-Belt, One Road” strategy, may contribute to China’s development model being more popular and gaining more supporters, challenging the US preference for democracy and a market economy. The United States palpably displays its discontentment with these development approaches, possibly pursued by the AIIB’s governing rules, and decided not to participate in it.

The United States emphasised the importance of certain agendas in the TPP such as the promotion of competition policy, which involves dealing with state-owned enterprises (SOEs), protecting intellectual property rights and enforcing labour standards, but China now considers such agendas very difficult to accept in international negotiations. To establish their preferred economic standards, the United States and China have commonly employed a coalition-building approach that entails attracting like-minded states into regional institutions and formulating arrangements designed to discourage the other superpower’s involvement. These two strategies pursued by both nations are intended to support their dominance in the standard-setting processes and negate all advantages of the other superpower.

This paper examines the reasoning behind Japan’s engagement in the TPP and non-commitment to the AIIB despite persistent requests by China for its participation by illustrating Japan’s increasingly assertive balancing behaviour with the United States vis-à-vis China amidst the ongoing Sino-U.S. power struggle over Asian geo-economic regionalism. Japan’s institutional balancing act as a way of strengthening relations with the United States is a sharp contrast with that of South Korea, which decided to join the China-led AIIB despite America’s strong opposition while failing to become a founding member of the TPP, and this paper aims to elucidate factors conducive to Japan’s regional behaviour.

Geo-economic regionalism in Asia

The end of the Cold War spotlighted geo-economics as a potentially important strategic concept , which was developed by Edward Luttwak, who argued the essence was “the logic of war in the grammar of commerce”. The geo-economics concept has re-emerged with more significant strategic overtones, and captured a key feature of the growing great power competitions between China and the United States in Asia. Notably, the chief purposes of establishing both the TPP and AIIB remain highly connected with the geographical context. The TPP’s geographical focus falls on countries in the Pacific Rim, whereas China’s One Belt, One Road initiative instead encompasses the Eurasian landmass. Many Eurasian states are categorised as developing countries, which find it difficult to accomplish high level economic liberalisation that the TPP requires, and their more urgent interests concern the needs of infrastructural development. The AIIB thus became popular among such countries. This trend in the Asian political economy can be phrased as geo-economic regionalism, which I define as regional economic institutions with clear demarcations and membership criteria, which powerful states are tempted to mobilise to supplement its national power through coalition-building processes with like-minded states.

China’s institutional voice strategy

In China’s 5th Plenum Communiqué issued in November 2015, the buzzword “institutional voice” emerged and was later incorporated into guidelines for the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020). It clarified China’s intention to impose its preferences upon systems of international governance. On the heels of the transatlantic crisis triggered by the 2008 bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, China began to view the existing global financial architecture—based largely on the U.S. dollar—as “a thing of the past,” to quote then-President Hu Jintao. By extension, current President Xi Jinping has since called for the realisation of the so-called Chinese Dream, involving both societal prosperity and national rejuvenation, which positions the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) as part of the grand design for Asian–Pacific integration. The proposed action would consequently give a cold shoulder to the TPP, which the United States has sought to promote as an economic pillar of its rebalancing strategy, with China as its primary target. Unsurprisingly, President Xi has also implicitly criticised the TPP in the 2015 APEC meeting in Manila, stating that “with various new regional free trade frameworks cropping up, fragmentation is becoming a concern.” Presidents Hu and Xi have thus clearly challenged U.S.-led global and regional economic orders, and some ambitions became realities in 2015.

Current trends further support China’s ambitions. In December 2015, the IMF admitted China’s renminbi to its basket of currencies that comprise its SDR, or its international reserve assets for use in currency-related and other crises. China’s position in the IMF became further strengthened by U.S. Congress’s approval of the long-awaited IMF reform package, which in aiming to increase the voting rights of emerging economies by reallocating quotas has made China the third largest contributor in the IMF, yet to only a slightly lesser extent than second-ranked Japan. These moves, which continue to sustain China’s growing institutional voices, are subsequently joined by the launch of the AIIB, which with $100 billion USD in capital has become a pivotal component of the Chinese version of the “rebalance Asia” strategy, especially toward Central and South Asia. The rapidly growing demand for infrastructural development in Asia, including railways, roads, and energy—estimated to cost 8 trillion USD during 2010–2020—cannot be fulfilled by existing multilateral banks, whose burden the AIIB promises to reduce. More importantly, however, AIIB can serve as a critical institution whose management and administration China can dominate without US or Japanese involvement.

Confronted with the TPP’s development, especially after Japan joined in July 2013, China accelerated the establishment of a regional FTA framework in which it could set its own standards for regional integration according to its own schedule. However, trade regionalism amid liberalisation and deregulation principles has made it difficult for any developing country with protectionist tendencies, including China, to play a leading role. The treatment of SOEs poses another major obstacle to China’s prospects for joining the TPP, whose policy seeks to ensure a level playing field for SOEs, or competitive neutrality between SOEs and private companies, despite exceptions for local SOEs and sovereign wealth funds, given the dominance of state capital in some of China’s key sectors, including petrochemicals, finance, and steel. China thus identifies development regionalism as more suitable than trade regionalism, for it can now capitalise on both having the world’s largest foreign reserves ($4 trillion) and being its largest developing economy.

China’s trade diplomacy seems to be designed to drive a wedge into the U.S.-led alliance network in the Asia-Pacific by creating regional institutions that favour its economic strengths. In 2015, China signed Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with two key US allies—namely, Australia and South Korea—whose substantial export dependence upon China, at roughly 33% and 25% each, has sustained their enthusiasm for the establishment of preferential trading relations with China via FTAs. Such political vulnerability stemming from excessive trade reliance on the Chinese market has in effect helped Australia and South Korea to dispel US pressure to not participate in the AIIB. China’s strategy of establishing more bilateral FTAs, especially with TPP members, would create more like-minded states that could be mobilised to help China’s political and strategic interests, as demonstrated by China’s massive flow of aid to Laos and Cambodia that has been instrumental in dividing ASEAN members on the South China Sea dispute.

The U.S. responses

In its policy, the United States has come to adopt the stance that China cannot be integrated into international institutions based on Western norms, given the risk that China could advance its national interests in those institutions, as readily shown by its challenges to existing institutional and normative structures in seeking to create alternative institutions. Indeed, the AIIB has been viewed as part of China’s potential institutional weaponry against the ADB, in which Japan and the United States serve as the two leading shareholders, at 15.7% and 15.6%, respectively. The United States once detailed potential shortcomings of the AIIB: its failure to meet environmental standards, procurement requirements, and other safeguards adopted by the World Bank and the ADB, including protections aimed to prevent the forced removal of vulnerable populations from their lands. These deficits reveal that the AIIB places inadequate conditionality on its lending with regard to environmental protection and workers’ rights, two significant agenda topics that the United States specifically incorporated into the TPP’s structure.

The United States has thus viewed the TPP’s substantial liberalisation, mostly via high standards for trade and investment, as catalysing interconnections in pursuit of common markets and shared economic rules that will ultimately reduce export dependence on China, a key factor in making many states susceptible to Chinese political influence. Observing the TPP’s basic agreement in October 2015, Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia expressed interest in joining the TPP, and the US–ASEAN Summit, slated for February 2016, is aimed at bolstering US endeavours to urge those and other ASEAN members to join the TPP in the near future.

Shinzo Abe and TPP

After Shinzo Abe returned to power in December 2012, Japan became more motivated to strengthen its alliance with the United States, as exemplified in Abe’s effort to pass new security legislation in the Diet in September 2015, which has promised to widen the role and scope of the overseas activities of Self-Defence Forces. Abe viewed the U.S.-led TPP as essential for not only its economic benefits, but also its geopolitical impact, and has often stressed the TPP’s role in sustaining U.S. regional engagement toward promoting regional security. The U.S.–Japanese commitment to the TPP conclusion in October 2015 illustrated the countries’ direct concern for China’s aggressive economic and strategic moves in the region, especially regarding the AIIB and the South China Sea.

Abe’s special interest in the TPP relates to interest in the universal values of freedom, democracy, human rights, and the rule of law as elements of a political foundation for economics-oriented rule making, thereby implying that TPP members will take collective action both economically and politically against countries that do not share those values, especially China. With this foreign policy orientation, Abe seems to view the exclusion of China as a major feature in the TPP. The significance of these common values originated during the first Abe administration in 2006–2007 due to Japan’s anxiety that the United States and China were becoming more closely tied, as insinuated by then-Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick’s “responsible stakeholder” statement that indicated a possible US–China partnership or G-2 within the U.S.-led international institution. The concept of common values was thus originally designed to arouse U.S. awareness that Japan, not China, shared America’s primary political and social values as part of a foundation for forging a more robust political and strategic partnership. In that light, Abe’s stress on universal values in support of Japan’s commitment to the TPP stemmed from his strong view that the potential U.S.–Japan partnership is vital for the successful launch of the TPP, which Abe expected to serve as not only an important instrument for accessing Asian-Pacific economic growth and for putting Japan’s economy back on track, but also for constraining China’s foreign policy ascendancy.

Japan’s institutional responses

Following American views on the AIIB, Japan under Prime Minister Abe did not join the AIIB, which it conceived as a challenge to the prominence of both it and the United States in the region’s economic order-creating. Indeed, Abe sceptically described it in the following manner: “a company that borrows money from a so-called bad loan shark may overcome immediate problems, but will end up losing its future. The [AIIB] should not turn into something like that.” The AIIB’s ascendance with the participation of major EU member states, however, has provided Japan with a new incentive to renovate its policies regarding infrastructure. In May 2015, Abe quickly responded by announcing a plan to increase investment in infrastructure in Asia by 30% to $110 billion during 2016–2020. Moreover, Japan promised to offer $6.2 billion of new ODA to the Mekong region, where China’s economic and political presence is dominant, by expanding the financial basis of domestic agencies, including the Japan Bank of International Cooperation (JBIC) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), by supplying funds from the private sector. In terms of fiscal investment and loan programs in 2016, JICA will take $4.1 billion and JBIC $11 billion, up by 20% and 70%, respectively, compared to the previous year.

Another incentive to beef up Japan’s Asian infrastructure-oriented policy also came from China, when Indonesia decided to offer China the Jakarta–Bandung high-speed rail project contract in September 2015, despite Japan having been involved in the project since 2008 and China for hardly more than half a year. Key components of the Chinese proposal include funding that does not require the Indonesian government to provide any guarantee or state budget and a completion timeframe of only three years, which means the project will conclude while President Joko Widodo is still in office. Moreover, China has agreed to jointly produce train cars not only for high-speed trains, but also electric and light rail, all of which would be used in the local train system. To support the program, China has even agreed to build an aluminium plant to provide raw materials to manufacture train cars. Overall, China’s offer—perhaps only to win the bid—seems to be overkill for only 150 km of railway. From one angle, China’s generous approach to Indonesia’s high-speed railway contract is a reflection of its eagerness to realise its One Belt, One Road initiative, a strategy in which Indonesia forms the eastern edge. The United Kingdom, another state to which China has promised massive investments in infrastructural development, including the construction of nuclear power plants, serves as the western end of this policy.

Japan’s loss to China’s bid was a blow to the Abe government’s policy aim to attain economic growth by expanding infrastructural projects overseas and Japan responded swiftly by shortening the application process from three years to one and by simplifying the implementation process by aligning paperwork needed for multiple steps, for infrastructure projects, especially those involving high-speed rail, which focused on improving quality. Japan has also become more expeditious in executing infrastructural projects in Asia by reducing funding guarantees by the recipient government from 100% to 50% in the case of yen loans, as well as by reforming the JBIC law to make risky infrastructure investments possible. Importantly, changes in quantity and quality in its aid policy, all in pursuit of Asian infrastructure, were decided without any clear decision on potential participation in the China-led AIIB.

Convergence of U.S.-Japan approaches

With China’s substantial engagement in Asian development issues, Japan became more motivated to push TPP as a way of potentially challenging against the AIIB. For instance, owing to TPP’s government procurement chapter, TPP members will be obliged to allow public bidding with common rules, including the equal treatment of domestic suppliers and companies in other TPP member states, for major infrastructure projects such as railway and highway construction. Eight members of the TPP, including Vietnam, Malaysia, and Australia, have yet to sign the WTO’s government procurement agreement that would ensure open and transparent conditions of competition in areas of government procurement. Their agreement to the obligation established under TPP to open overseas public tenders for any projects worth at least ¥1 billion is, thus, considered to benefit Japanese companies, including Hitachi and Mitsubishi Electric, which issued positive reactions to the deal.

The emphasis of Japanese companies and the government on the potential benefits of this requirement partly relates to the fact that the AIIB may face difficulty in regard to investment related to government procurement, particularly given a Chinese law stipulating the favourable treatment of domestic products in its government procurement. Such regulations have been criticized by the United States and Japan as discriminatory, preventing the participation of foreign companies in China’s bidding procedures. With the most liberalized government procurement regime at home, Japan and the United States strongly supported this provision’s inclusion in the TPP.

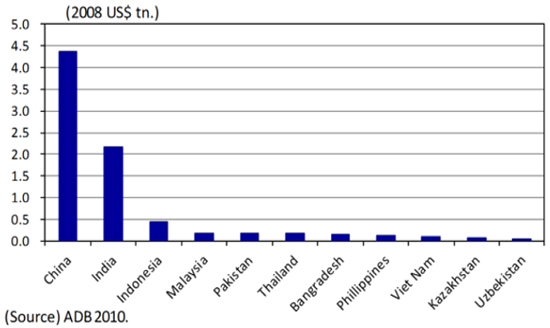

The United States and Japan also came to share the same basic stance on the AIIB, at least according to their reasons for not joining. For one, the AIIB will undercut existing institutions and could loosen lending standards. Furthermore, given the requirement for “fair governance,” some infrastructural projects may be unsustainable, particularly in posing too much of a burden on the environment. Lastly, the AIIB may not prevent taxpayers’ money from being used without restriction due to the lack of transparency. The often highlighted 8 trillion USD of demand for infrastructure projects in Asia can be questionable as China dominates the figure (nearly 4.5 trillion dollars) as seen in the figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Demand for Infrastructure in Asia

China can theoretically manipulate the AIIB to help China’s own infrastructure demands with the money coming from more experienced other nations and financial institutions with skilful expertise. This moral hazard problem should also be clearly presented. In sum, since the AIIB will not mitigate these undesired effects that contradict current US and Japanese rules and norms concerning foreign aid and infrastructure investment, neither country has sought participation in the organisation. This assessment seemed to be sustained by Chinese Minister of Finance Lou Jiwei, who indicated that China has little appetite for rules that the United States and Japan have cherished, given his claim that “the West puts forward some rules that we don’t think are optimal.”

Conclusion: Implications of Asian geo-economics

The upsurge in geo-economic regionalism in Asia is a sign of the intensifying Sino-U.S. struggle to shape the regional economic and political order, imposing one’s own sets of norms and rules on regional political and economic agendas. The general agreement reached in the TPP ministerial meeting in Atlanta in October 2015 raised the cost of non-participation in the partnership; outsiders will continually fail to secure maximum trade and investment benefits. The estimates made by a 2016 World Bank report support this view; Vietnam is expected to enjoy the largest gain of 30.1% increase in exports, followed by Japan at 23.2%, putting pressure on their non-participating neighbours, such as Thailand and South Korea, whose exports would decrease due to the trade diversion effects. So, whether or not China’s participation in the TPP is possible is the crux of the argument in this new era of Asian regionalism. Michael Froman, US Trade Representative, set the conclusion of a bilateral investment treaty with the United State as a precondition for China’s entry by declaring “it’s a good test case to see whether China is willing and able to meet the high standards that we insist on.” Furthermore, entry into the TPP as a latecomer will also require China to accept all 31 chapters agreed upon by the 12 current member states, including those regarding environmental standards and stronger intellectual property rights, which will leave China little room to introduce national preferences into the agreement’s structure. At this point, however, it may still be difficult for China to become ready to commit to the TPP’s high-standard agendas. Nevertheless, the TPP and RCEP, which China hopes to promote as regionalism on trade, are too different to be merged into one order. The differences between them include, among other factors, notable variations regarding competition policy related to SOEs, so the mutual exclusiveness continues to exist, symbolising the strategic rivalry between China and the United States.

It is safe to assert that American and Japanese participation in the AIIB is currently unlikely. China has already clarified that the AIIB’s loan rule would not involve any political conditionality, including the protection of human rights, in order to focus on building infrastructure and delivering finances quickly, which differentiate it from the ADB’s purposes—namely, to reduce poverty. ADB normally provides a return rate of only 1% for basic infrastructural projects, while China’s historical records illustrated that some cases in Pakistan and Thailand, China’s SOEs involved in infrastructure projects required a rate of 6%. This non-Western approach possibly pursued by AIIB continues to discourage the United States and Japan from viewing the AIIB positively and to stress the value that they place upon respecting freedom, human health, and the environment in their engagement in infrastructure projects. Indeed, this is the essence of President Obama’s repeated statement, “If we don’t write the rules, China will write the rules out in that region.” As a response to President Obama and Prime Minister Abe perhaps, the ADB also endeavoured to maintain competitiveness and attractiveness by undertaking major reforms including implementing more streamlined procurement processes, quicker approval processes for key projects, and the possible consolidation of the Asian Development Fund and the Ordinary Capital Resources, its two main financial instruments.

Set to begin operation in 2016, the AIIB has been touted by its president, Jin Liqun, as a “clean lean and green” multilateral bank with the highest international lending standards in terms of environmental and social issues, as well as being far faster than any other in existence. If all of this were realised, then it would be a result of American and Japanese decision not to participate given their scepticism, yet all the while enhancing the possibility of their eventual participation, making the geo-economics viewpoint on Asian regionalism almost meaningless and creating more stability in the regional order-building process. ■

The East Asia Institute takes no institutional position on policy issues and has no affiliation with the Korean government. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in its publications are the sole responsibility of the author or authors.

Center for Japan Studies

Center for Trade, Technology, and Transformation

Future of Trade, Technology, Energy Order

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20240419123938102197065(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections

Niranjan Sahoo | 2016-02-03

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2024032815145548472837(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?

Ken Godfrey | 2016-02-03