Yul Sohn is a Professor of International Studies at Yonsei University. He received his Ph.D in political science from the University of Chicago. He teaches Japanese political economy, East Asian regionalism, and International political economy.

Aso’s Two Visions

In a series of town hall meetings during the winter of 2005–2006, Aso Taro, then Minister of Foreign Affairs under the Koizumi cabinet, introduced an interesting concept of Japan’s role in Asia. Japan can and should play the role of a “thought leader,” who through fate has been forced to face certain very difficult issues earlier than others. Because Japan has put great effort, both monetarily and socio-politically, into resolving issues that include ultra-nationalism, an aging society, and environmental protection, it has become the forerunner for other Asians to emulate (Aso 2005). This role as a soft power leader contrasts with the existing hard power–oriented (i.e., economic) discourse of international contribution as well as the conventional soft power discourse that is rooted in the Japanese culture and sensibilities, such as animation, fashion, and cultural products. Japan’s strength lies in the firstmover knowledge it provides for Asia, creating a network of knowledge available to others (Aso 2006).

Three years later, Aso, this time as the Japanese Prime Minister, proudly announced a "Growth Initiative" that planned to double the current scale of Asia's economy by 2020 (Aso 2009a). This initiative, Aso’s first and thus far most important vision for Asia as Prime Minister, is aimed at moving Asia's economy from one driven by exports to one led by domestic demand, through encouraging region-wide development and expanded consumption. To make this effort, Japan has committed (a) US$20 billion in overseas development assistance (ODA); (b) US$20 billion for infrastructure development in Asia; (c) US$5 billion over two years for an initiative investing in Asian environmental projects; and (d) US$22 billion over two years to provide additional support for trade financing in order to underpin trade credit, and so on. Japan will mobilize all possible policy measures to support the efforts being made by Asian countries. In addition, Aso seeks to increase the attractiveness of Japan by utilizing cultural sources (such as manga, animation, fashion, authentic food) to create jobs in Japan and the region (Aso 2009b).

Aso’s recent initiative appears to have tilted in a direction different from his earlier vision of Japan as a thought leader, a well thought out and creative idea. Today, given Japan’s rapid economic contraction caused by its “once in a century” crisis, Japan finds it difficult to attain the regional leadership it desires merely by spending more money. Utilizing cultural resources will yield only a limited outcome. Finally, the initiative is targeted at Southeast Asia and the Pacific, with few attempts to assist or engage the members of Northeast Asia such as China and South Korea. Japan has so far failed to play its desired role as a thought leader for Asia. The inconsistency between words and actions underlines the strategic dilemmas that Japan has faced as China has risen to be a formidable rival in the region.

Japan’s New Regionalism to “Soft Balance” China

Japan’s regional policies have been concerned with an increasingly powerful China. It has displaced the United States as Japan’s largest trading partner, and it has begun to be positioned increasingly at the hub of the regional economy. Chinese military modernization, fueled by double-digit growth in arms-related spending for more than a decade, has resulted in a dramatic improvement of virtually all the key elements that enable China to achieve real military options in the region. Further, Beijing has taken dramatic steps toward diplomatic leadership (Shambaugh 2004/05; Kurlantzick 2007). The Chinese have toned down their military actions and instead have focused on building soft power. Beijing has cultivated its influence in Southeast Asia while at the same time displaying its diplomatic skills as a mediator in the Six-Party Talks in Northeast Asia.

For many in Japan, nothing has been so disturbing as the rise of China (Pyle 2007, 312). The dramatic growth of China’s economic, political, and military influence, combined with China’s intense historically based mistrust of Japan, caused alarm, which was intensified by uncertainty about China’s future plans. Seeing China as a threat, Japan wanted its ally the United States to balance the danger. Yet, U.S. forces have been reduced and redeployed almost unilaterally in the context of the war on terror.

Strengthening Japan’s military alliance with the United States was a plausible course of action. Under the leadership of Koizumi Junichiro (2001-2006) and subsequent Prime Ministers, Tokyo worked hard to improve its military relations with Washington. Along with Koizumi’s dispatch of naval forces to the Indian Ocean and deployment of ground forces to Iraq, the U.S.-Japan Security Consultative Committee (the socalled Two-plus-Two meeting) has been the driving force for not just “force transformation” (that is, joint force modernization and realignment) but also “alliance transformation” (that is, a more balanced, more equal, and more normal relationship between Japan and the United States) based on shared understandings of the new security environment shaped heavily by China threat.

There were limits to the military balancing that was possible, however. Japan did not want a military confrontation with its vital economic partner (Mochizuki 2007; Samuels 2007). Likewise, economic balancing— strategically reducing economic interdependence with China—was not feasible because few alternative markets were available. Equally important was the byproduct of military integration: as Pempel puts it (2009), “Japan’s overemphasis on military posture risks exacerbating fears among Asian neighbors, which divert attention from its true strength in nonmilitary diplomacy and global appeal.” Given its shrinking economic resources available for regional competition, combined with its limited military usefulness, Japan has needed soft power—the power of ideas and visions that enable Japan to attract others in the region.

Elsewhere I have characterized a series of regional policies pursued by Japanese leaders as a “soft balancing” against China’s charm offensive (Sohn 2008). Given the Chinese initiatives that have increased its influence in the region, Japan turned with hope to a regional design that would counter Chinese initiatives while attracting other Asians. Under the leadership of Koizumi, Tokyo proposed the East Asian Community (EAC) vision and the Arc of Freedom and Prosperity vision, both in 2005. Two years later, Prime Minister Fukuda Takeo declared the “Asia-Pacific Inland Sea” vision.

The EAC vision aimed to counter Chinese influ-ence in the region. First, in contrast of Beijing’s vision of a rather exclusive “Asia-only” regionalism that rep-licates the ASEAN Plus Three (APT: China, Japan, South Korea) membership, Japan pursued an open re-gionalism in which the boundary is porous. Second, it emphasized the gemeinschaft-like concept of com-munity (kyōdōtai) in which the universal yet Western values such as freedom, democracy, and human rights are the bond. Third, the value-based community boosted the democratic memberships of Australia, New Zealand, and India. Tokyo believed that a community holding universal values and a balanced membership would give Japan strategic leverage as well as confidence that China would not gain a dominant position, and at the same time would alleviate American concerns about a closed regionalism.

Similarly, the Arc of Freedom and Prosperity that supports budding democracies lining the outer limits of the Eurasian continent from Northern Europe to Central Asia to Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia can easily be interpreted as encircling China by supporting the growth of democracy along China’s borders (Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2007). The Arc is another attempt to establish a value-based community that can be attainable through cooperation in the areas of trade and investment as well as through official development assistance to provide for basic human needs and enable democracy to take root.

Finally, in the Asia-Pacific Inland Sea vision, Japan works together with Asia and the United States to promote economic partnership by forming a network of countries for which the Pacific Ocean is an inland sea. This builds an open regionalism that will not undermine core American interests in Asia. It is no coincidence that this vision came after renewed U.S. efforts to revitalize Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and, to the surprise of many, propose the Free Trade Agreement Asia Pacific.

These three visions were put forward within three years after the idea of Japan as Asia’s thought leader was born. All derived from concerns that China’s power in Asia ought to be balanced by the policies of its neighbors. All were focused on embracing Southeast Asia, an emerging battleground between China and Japan. Finally, all were concerned with checking the development of a potential “Asia-only” regionalism that might undermine the role of the U.S.-Japan alliance. Although these visions share the same objectives, they reveal striking differences in terms of the scope of their membership and the nature of their regional commonality. These differences may leave the impression that Japan’s regional vision changes too often and varies too much. Moreover, if soft balancing is meant to work in ways that enable Japan to attract other Asians to counter Chinese influence, the policy has failed. In the end, Japan is not a thought leader.

Better Ways to Embrace Asia

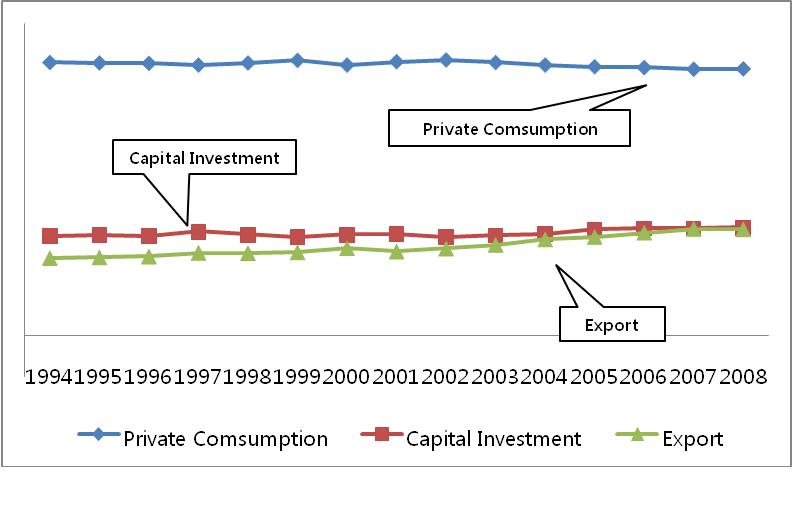

While the politics within the region have been fraught, the global financial crisis makes Japan more entangled with Asia than ever. Japan’s economy contracted 15.2 percent in the first quarter of 2009 at the fastest pace since records began in 1955 and the fourth straight quarter of negative growth. Exports plunged 26 percent in that quarter, the steepest decline on record. The latest numbers underscore the vulnerability of a nation that for the past decade relied on international trade to fuel growth. The Japanese economy is slumping much faster than others because it depends on foreign market demand. Until the economy started contracting in 2008, Japan enjoyed the longest economic boom (69 months from February, 2002), thanks to increases in exports to fast-growing economies such as China. With domestic demand and fixed capital investment remaining static, exports led to growth (see Figure 1).

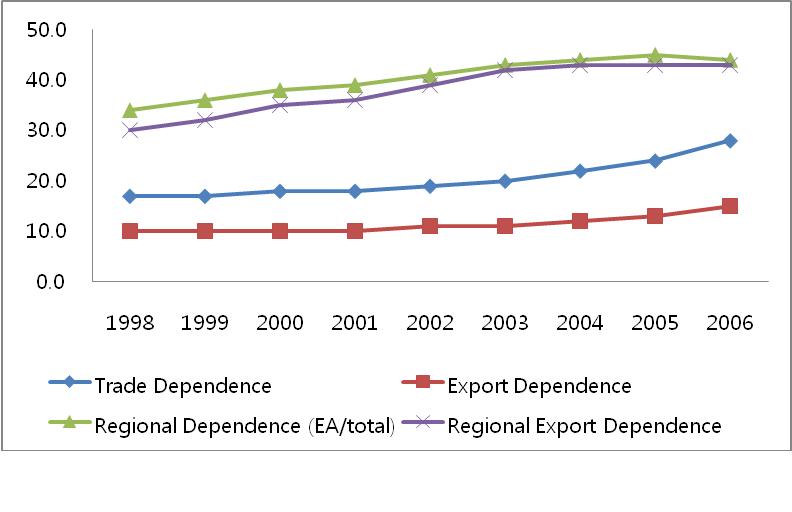

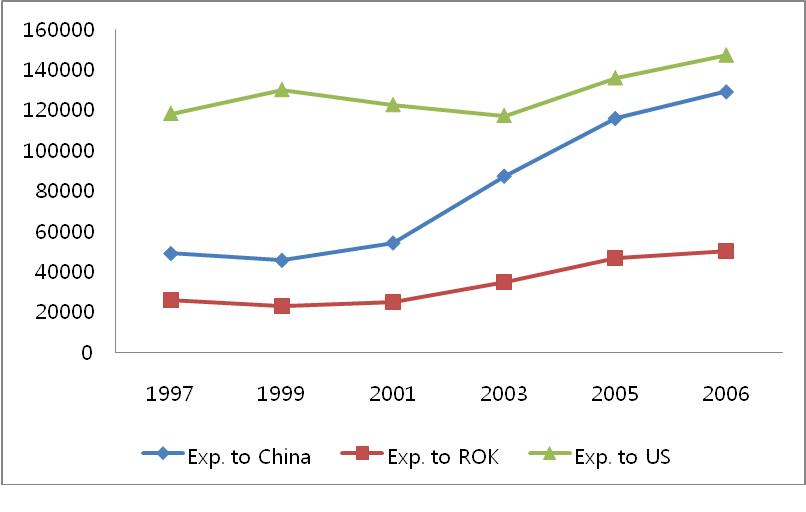

As Figures 2 and Figure 3 demonstrate, Japan’s recovery followed by the steady growth was in large part propped up by its increasing exports to China and other Asian markets. During 1996-2006, Japan’s China exports have sharply increased while its U.S. exports have steadily declined. Reflecting China’s boom, Japan’s East Asian export ratio also increased by more than 50 percent. Without corresponding increase in private consumption and investment, Japan was hit hard by a rapid decline in exports to China and other East Asian nations as well as the United States since the sub-prime mortgage crisis spread over the globe. After growing 12 percent in the first half of 2008, Japan's exports to China began to erode in October, and fell 36 percent in December.

Figure 1 The Ratio of Comsumption, Investment, and Exports in Japan’s GDP

Figure 2 Japan’s Export Trade, 1997-2006

Figure 3 Japan’s Export Trade (Percentage)

These data signal that Japan’s economic fortune depends on Asia far more than on any other region. Japan should rebalance its Asia strategy. Monetary contribution such as the growth initiative will not be sufficient. Japan needs to embrace Asia far more, well beyond the scheme of soft balancing. A few points fol-low.

A Networked Understanding of the Region

A huge irony is often found in Japanese concerns about regionalism. Though Japan fears a regionalism that might isolate the United States, the United States has no parallel fears about regionalism. Indeed, most American policymakers would welcome a healthy regionalism if the United States has secure access to other channels of the network that connects only Asians together.

Japanese concerns stem from a historical legacy that led Japan’s leaders to conceive of the region as the antithesis to the West. In the period after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the tendency of to see a binary opposition of the East versus the West prevailed. When the West was conceived as a physical threat to Japan’s independence, the idea of regional cooperation against the Western powers developed. Likewise, when the West was thought to be a spiritual threat to Japan’s authentic culture, a similar idea, that Asian cultural autonomy was threatened by Western traits, emerged (Najita and Harootunian 1988). In support of these ideas, there developed an imagined community where non-Western cultural traits prospered. Asia (Japan) and the West were sharply divided. Japan’s pre-surrender regionalism invariably contained anti-Westernism.

As Japan entered the postwar period, given its obsession with an alliance with the United States, it found it could not reconcile itself with a regionalism that sounded anti-West. While keenly aware of Japan as a member of Asia, policymakers unambiguously emphasized the importance of cooperation with the West (Oba 2004). The result has been the worry that as Japan becomes a more significant player of regionalism, the United States will downgrade its long-standing relations with Japan. Although the Asian financial crisis of 1997 gave a boost to Japanese expectations for East Asian regionalism centered on APT, Tokyo made only stuttering steps forward.

An Asia-Pacific that embraces both East Asia and the United States remains the most comfortable concept for Japanese policymakers. Accordingly, APEC is the most appropriate regional arrangement, despite the fact that it proved ineffective in the midst of the Asian financial crisis of 1997.

The effectiveness of APEC as a regional body is limited because it is geographically too large and culturally and economically too diverse. Instead of adhering to a futile Asia-Pacific vision such as Fukuda’s inland sea idea, Japanese leaders should realize that the “network” concept can guide Japan’s regional policy in ways that overcome the traditional notion of binary opposition. A network in which actors are linked through enduring relations assumes that its boundary is porous and flexible. If new requirements or problems arise, networks can adapt by recruiting new nodes with relevant expertise. Here, the efficacy of a network depends on the ability to grow not only by recruiting new members but also by linking horizontally to new networked groups (or other set of nodes).

By understanding the region as a networked structure, Japan can avoid pursuing an impracticable mega-region like APEC or adding the United States into a regional body. It can connect with the Asian groups and link horizontally to the United States. Such an arrangement will ensure that the United States can stay connected with Asia via Japan. For example, the United States will most likely accept any kind of Asian multilateral free trade agreement (FTA) as long as the United States itself is linked to the region through bila-teral FTAs with key nodes (i.e., Japan or South Korea).

Japanese leaders have long claimed that their nation can serve as an honest broker, with one foot in the East and another in the West. But they have failed to define the conditions for honest brokerage. Instead, from a network perspective, Japan as a thought leader should provide or affirm for the networked actors common goals, values, or other considerations sustaining collective action. This collective perspective will ensure that networks do not end up splintering. Second, because new members prefer to link to a node that is densely linked to other nodes or a set of nodes (Kahler 2009), older members need to increase their ability to make others want to link to them and to do so by delivering knowledge based on Japan’s first-mover experience.

Searching for a Complex and Networked Cooperation

Related to this is the need for a renewed understanding of the U.S.-Japan alliance transformation. As mentioned earlier, a traditional military alliance is necessary yet insufficient to deal with Japan’s new strategic dilemmas. There are few reasons for Japan to further integrate its alliance relationship with the United States. Japanese leaders should recognize that what is needed is not tightening up but transforming the alliance structure into a complex one. As the 2006 U.S.-Japan Summit called for in the Alliance for the New Century, the bilateral alliance includes not only military but also nonmilitary cooperation in a wide range of areas. Coordinating with the United States, Japan can play a valuable role in nonmilitary affairs such as development assistance, environmental protection, transnational crimes, and humanitarian assistance. This soft approach will enhance Japan’s power more effectively than a hard alliance would.

Equally important is the need for a more open and flexible alliance structure. Asia is rapidly transforming into an increasingly networked region through new cultural links, new business deals, and new bilateral and multilateral diplomatic efforts. As Campbell et al. (2008) have noted, “Asia features new interfaces of increasingly independent actors who constantly interact in bilateral and multilateral, private and public, old and new ways.” Japan’s security interests in Asia cannot be guaranteed by simply managing the existing alliance. A networked alliance must be developed that is better adapted to power relations and changes that typify today’s Asian strategic reality. In contrast to a fixed bilateral relationship, the network concept guides a scalable alliance: that is to say, an alliance that recruits new members and links horizontally to other forms of groups (i.e., regionalism). Tokyo has worked hard to add Australia and India into its bilateral alliance with the United States. Abe Shinzo (2006) once tried a democratic alliance. Together, a recent policy proposal asks for a comprehensive strategy that links alliance with community (EAC) (Tokyo Foundation 2008). In order to realize these goals, Japanese leaders must find ways to make the existing alliance more open and scalable.

Japan is in crisis, with its worst economic record in modern history. Accordingly, the availability of economic tools in its foreign policy is limited. Worse, its most important ally is in crisis as well. The power of balance, smart power diplomacy, a balanced strategy—all these concepts signal that the United States will be sharing power with its key allies. Japan will be pressed for more active involvement in regional and global affairs. Finally, Asia is rising. Japan’s economic future will be increasingly dependent on Asia in general and China in particular. An embrace of Asia is an imperative.

Japanese leaders must recognize that in order to remain a cornerstone of America’s Asia policy, the increase of its soft power is critical, and that in order to embrace Asia, the same is true. The overly economic Asia 2020 vision is misplaced. The promotion of cultural items such as animation, fashion, and foods as the source of soft power is partial at best. Struggling with the history issue that undercuts Japan’s soft power and strategic value is anachronistic. Japan’s future lies in its ability to become a thought leader in Asia. The decentralized yet tightly interconnected nature of networks enables an actor with particular expertise to prosper. Japan will be able to play a role as a thought leader if it is equipped with the network concept, experiments early, and demonstrates new, flexible models of alliance linked with other forms of regional organizations. ■

Major Project

Center for Japan Studies

World

![[EAI Issue Briefing] Expectations and Challenges for Improved Relations with “Unfavorable” China under the Lee Administration: 2025 EAI Public Opinion Poll on East Asia](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2025070114329345217651(0).jpg)

![[EAI Issue Briefing] The Public Prioritizes a Future-oriented Cooperation over Resolving the History Problem in Korea-Japan Relations: 2025 EAI Public Opinion Poll on East Asia](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20250627164526777359170(0).jpg)