![[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅱ)](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/2025042817536795173098.jpg)

[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅱ)

Working Paper | 2024-12-27

Asia Democracy Research Network

Active citizen participation in democratic decision-making?through formal mechanisms such as elections and political parties, alongside the roles of media and civil society organizations?is vital for ensuring governmental accountability. The Asia Democracy Research Network (ADRN) conducted research to examine gaps between vertical accountability institutions and their implementation across the region, while identifying key reforms for the future. As part of this initiative, EAI published a series of working papers analyzing cases from the Philippines and Taiwan. The research underscores the importance of political parties in aggregating interests and engaging citizens to replace underperforming governments. Additionally, it highlights the need to balance representative mechanisms with direct democratic processes, such as referendums and recall elections, to enhance accountability and responsiveness in governance.

In 2022, Asia Democracy Research Network (ADRN) selected horizontal accountability by the ability of state institutions to hold the executive branch accountable, and vertical accountability through elections, parties and citizens’ participation, as the requirements to accomplish robust and sustainable democracy in Asia.

Against this background, ADRN published this report to evaluate the current state of the trends and trajectories of vertical accountability in the region by studying the phenomenon and its impact within countries in Asia, as well as their key reforms in the near future.

The report investigates contemporary questions such as:

● To what extent are elections free, fair, and inclusive, and multi-party in practice?

● To what extent are political parties unrestrained in their foundation and activity?

● How effective does the media provide diverse political perspectives?

● To what extent do citizens voluntarily engage in CSOs, operated without interference?

● To what extent are citizens free to express their views without fear of suppression?

● What should be done to improve the state of vertical accountability performance?

Drawing on a rich array of resources and data, this report offers country-specific analyses, highlights areas of improvement, and suggests policy recommendations to fulfill methods of vertical accountability in their own countries and the larger Asia region.

Vertical Accountability:

Reforming Representation in the Philippines

Francisco A. Magno[1], Anthony Lawrence A. Borja[2], Jeuny Mari D. Custodio[3]

De La Salle University

1. Introduction

The Political landscape of the Philippines is dominated by the rich and the famous. This unfortunate situation is abetted by the underdeveloped character of political parties in the country. Political parties are important actors in a democratic systеm. They are expected to provide an organizational avenue for the aggregation of interests, the formulation of policy choices, the cultivation of leaders, and the engagement of citizens in electoral processes and the holding of governments to be accountable for their actions. For the longest time, they are the key organizations for political and democratic representation (Deschouwer 1996; Katz 2006; White 2006).

However, historical evidence indicates that Philippine political parties frequently prioritize the narrow objective of providing partisan vehicles for candidates seeking election rather than mobilizing the public in pursuit of coherent policy programs that would benefit the general population. Consequently, candidates are selected on their ability to command resources and their potential for success in an election, rather than on the strength of their commitment to specific policies, values, and principles (Hutchcroft 2020; Hutchcroft and Rocamora 2012).

The weak party systеm in the Philippines has contributed to the rise of populism and the erosion of the essential checks and balances that are vital for a vibrant democracy. Given the lack of effective disciplinary structures within political parties, politicians, including legislators typically align themselves with the party or parties of the winning presidential candidate. This facilitates the deterioration of legislative oversight and the advancement of executive aggrandizement.

Overall, analyzing the case of the Philippines as a defective democracy (Rivera 2016; Teehankee and Calimbahin 2020) that is more oligarchic than democratic, this paper elaborates on what Arugay (2005) described as an accountability deficit or the lack of accountability among government officials that has led to abuse and corruption. From a historical and structural perspective, this can be linked to the long-standing rule of oligarchs whose sense of accountability is based more on their relations with one another (e.g., inter-elite patronage) than their constituents (Hutchcroft and Rocamora 2012; Rivera 2016).

If political parties and electoral systеms are central to democratic governance, especially by serving as the primary conduits for citizen participation and government accountability, then questions about the effectiveness of these institutions in representing and responding to the electorate necessitate evaluation. It becomes a matter of fleshing out and substantiating political representation in terms of both supply (i.e., legal and political structures concerning elections and political parties) and demand (i.e., citizen-leader relations and the bottom-up demand for accountability) for vertical accountability.

From this viewpoint, vertical accountability becomes a question of values, expectations, and institutional arrangements that can facilitate the confrontation between the decision-making processes of citizen voters and policymakers (cf. Svolik 2013). Placed in electoral cycles, it ultimately becomes a matter of whether vertical accountability is pursued under virtuous (i.e., democratizing) or vicious (i.e., oligarchic) conditions.

Scholars have long mapped and tracked the idea of creating an environment where elections are considered avenues to obtain accountability from the elected. The concept of accountability has long been declared to be integral to democratic theory (Hellwig and Samuels, 2008). Vertical accountability, as a concept, is framed between political representation and democratic responsiveness, whereas Hellwig and Samuels (2008) echo that in many empirical studies, a systеm of incentives and disincentives is put in place by the electorate. Through this systеm, every vote functions as an executive decision to either reward or punish the incumbent accordingly, depending on economic conditions per term served by the elected.[4]

This paper examines the functionality of the electoral systеm and political parties in the Philippines in terms of representing voters, aggregating interests, crafting policies, cultivating leaders, and engaging citizens – substantiating a sense of responsibility among elected officials. Additionally, it investigates mechanisms beyond elections that allow the public to demand change and proposes reforms aimed at strengthening political parties and the electoral systеm to enhance accountability and voter representation.

This study addresses the following questions: Do elections and political parties function well to represent voters? How effective are political parties in aggregating interests, crafting policies, cultivating leaders, and engaging citizens to hold governments accountable through the electoral process? How can political parties be strengthened as institutions of representation in Philippine democracy? Can voters replace the government easily when it fails popular expectations? What are the existing institutional mechanisms that allow the public to demand change beyond elections? What kinds of political and electoral reforms are needed to promote voice and accountability?

The current study illustrates that alongside limitations in the electoral and political party systеms in the Philippines, there is a value systеm leaning more toward giving more license to leaders to act autonomously instead of holding them accountable as public servants. This paper is organized accordingly to probe the different dimensions of vertical accountability. The first section provides an overview of the electoral and political party systеms of the Philippines. The second section analyzes representation from a psycho-political perspective via citizen-leader relations. The third section conducts a general assessment of the supply and demand side of vertical accountability before opening areas for reform in the fifth section. The concluding section considers the avenues for the great dance between theory and practice relating to political representation in the Philippines and in comparison with its Southeast Asian neighbors.

2. The Electoral and Political Party Systеm of the Philippines

Regarding the supply side (structural-institutional) of vertical accountability, the Philippines faces the twin problems of a pluralistic electoral systеm and a weak party systеm. Both target the essence of majority rule in terms of quality and quantity. The pluralistic “first-past-the-post” electoral systеm of the Philippines places government leaders in a “winner-take-all” situation. This pluralist systеm, tied with patronage and turncoatism as the norms of the ruling elite, combines a weak popular mandate with super-majorities in the legislative branch, which can weaken the voice of criticism and opposition within the halls of government. Consequently, it also makes policymakers less accountable to the citizen-voter after elections and is especially true for those who end up as members of such patronage-driven super-majorities.

Adding to the limitations of the electoral systеm, a weak party systеm driven by entrenched structures of patronage and clientelism also characterizes Filipino politics (Hutchcroft and Rocamora 2012; Rivera 2016). In turn, this forms the core of what Teehankee and Calimbahin (2020) recognize as the defective democracy of Filipino politics, wherein regular elections merely serve as a means to legitimize members of an oligarchy and account for the anarchy of parties characterized by the proliferation of such organizations that are driven more by patron-client relations and money politics rather than party discipline and distinct political programs (Kasuya and Teehankee 2020). While there is a lack of incentives to maintain a strong chain of accountability between electors and the elected, there are more incentives facing elected officials to attach themselves to a patron.

A bridge between the authoritarian regime of Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and the post-authoritarian period, the Omnibus Election Code of the Philippines serves as the primary legal framework underpinning elections in the Philippines since its ratification by the former, with the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) serving as the primary enforcer of the Omnibus Election Code. Though this study will not provide a comprehensive analysis of the Omnibus Election Code and COMELEC (see Caritos and Yadao 2024; Maambong 2001), it highlights the following points related to vertical accountability.

First, the Omnibus Election Code is supplemented by a series of legislations listed in Table 1 below. These have been formulated, in general, to improve the integrity and pursuit of the electoral process (e.g., laws concerned with automation and biometrics) and to facilitate a more inclusive systеm of representation and electoral participation positively through laws like the Party-List Systеm Act of 1995, and negatively by reducing barriers to fair participation among candidates (e.g., Electoral Reforms Law of 1987, Fair Election Act of 2001). As Caritos and Yadao (2024, 229) state, these supplementary laws “involve the introduction of new electoral laws aimed at addressing issues, including the empowerment of vulnerable sectors, improvement of electoral competitiveness, regulations on campaign finance, and the integration of technology into the electoral process.”

Table 1. List of Related Electoral Laws

|

Number |

Title |

|

E.O. No. 157, s. 1987 |

Providing For Absentee Voting By Officers And Employees Of Government Who Are Away From The Place Of Their Registration By Reason Of Official Functions On Election Day |

|

E.O. No. 292 (Book V, Title I, Subtitle C), s. 1987 |

The Constitutional Commissions: Commission on Elections |

|

R.A. No. 6646 |

Electoral Reforms Law of 1987 |

|

R.A. No. 6735 |

Initiative and Referendum Act of 1989 |

|

R.A. No. 7160 |

Local Government Code of 1991 |

|

R.A. No. 7166 |

Synchronized Elections of 1991 |

|

R.A. No. 7941 |

Party-List Systеm Act of 1995 |

|

R.A. No. 7787 |

An Act Instituting Electoral Reforms For The Purpose Of Amending Section 3, Paragraphs (C) And (D) Of Republic Act No. 7166 (1995) |

|

R.A. No. 7890 |

An Act Amending Article 286, Section Three, Chapter Two, Title Nine Of Act No. 3815, As Amended, Otherwise Known As The Revised Penal Code (1995) |

|

R.A. No 8173 |

An Act Granting All Citizens’ Arms Equal Opportunity To Be Accredited By The Commission On Elections, Amending For The Purpose Republic Act Numbered Seventy-One Hundred And Sixty-Six, As Amended (1995) |

|

R.A. No. 8189 |

Voter Registration Act of 1996 |

|

R.A. No. 8295 |

Lone Candidate in Special Elections of 1997 |

|

R.A. No. 8436 |

Automated Elections Systеm Law of 1997 |

|

R.A. No. 9006 |

Fair Election Act of 2001 |

|

R.A. No. 9189 |

Overseas Absentee Voting Act of 2003 |

|

R.A. No. 9225 |

Citizen Retention and Re-acquisition Act of 2003 |

|

R.A. No. 9224 |

An Act Eliminating The Preparatory Recall Assembly As A Mode Of Instituting Recall Of Elective Local Government Officials, Amending For The Purpose Sections 70 And 71, Chapter 5, Title One, Book I Of Republic Act No. 7160, Otherwise Known As The “Local Government Code Of 1991”, And For Other Purposes (2004). |

|

R.A. No. 9369 |

Revised Automated Election Law of 2007 (amending R.A. No. 8436) |

|

R.A. No. 10367 |

Mandatory Biometrics Law of 2012 |

|

R.A. No. 10366 |

An Act Authorizing The Commission On Elections To Establish Precincts Assigned To Accessible Polling Places Exclusively For Persons With Disabilities And Senior Citizens (2013) |

|

R.A. No. 10590 |

Overseas Absentee Voting Act of 2003 (amending R.A. No. 9189) (2013) |

|

R.A. 11207 |

An Act Providing For Reasonable Rates For Political Advertisements, Amending For The Purpose Section 11 Of Republic Act No. 9006, Otherwise Known As The “Fair Election Act” (2019) |

Second, focusing on campaign financing in the Philippines, the Omnibus Election Code and RA 7166 set it to PHP 10 (USD 0.20) per voter for president and vice president and PHP 3 (USD 0.06) per voter for senators and representatives (with party lists considered as one candidate). For those without any political party or support from a political party, such candidates are allowed to spend PHP 5 (USD 0.08) per voter in their respective constituency. Despite these modest standards, Co et al. (2005) and Eusebio (2021) cite problems ranging from exorbitant spending to the concentration of funding at the hands of individual candidates rather than parties. Furthermore, as Co et al. (2005) note, deviation from these standards renders candidates vulnerable to rent-seeking behavior from private interests, while incumbent candidates with access to government funding can gain an advantage at the expense of non-incumbents. In other words, money becomes the key to electoral victory. To illustrate the extent of aggressive campaign financing, estimations from Eusebio (2021) in Table 2 below show that during the 2007 elections, excess was the norm for major elected positions.

Table 2. Estimated Extent of Unregulated Campaign Finance in the 2007 General Elections

|

Position and Estimated. Average Voting Population (2007) |

Commonly Known Max. Estimated Cost (PHP) |

Estimated Allowable Costs (PHP) |

|

City Mayor (1,092,809) |

10,000,000 |

3,278,427.00 |

|

Governor (1,520,893) |

150,000,000 |

4,562,679 |

|

Senate (48,221,863) |

500,000,000 |

144,665,589 |

|

President (48,221,863) |

5,000,000,000 |

482,218,630 |

In 2022, the COMELEC, through Resolution No. 10730 under Republic Act No. 9006 (Fair Election Act of 2001), affirms the PHP 674 million cap for presidential and vice presidential candidates. Within this limit, data from the COMELEC (as cited in De Leon 2022) shows the expenditures for presidential and vice presidential candidates remain severely asymmetrical. Tables 3 and 4 show that gaps between candidates are wide enough to cast doubt over the supposed fair competitiveness of elections, at least in terms of campaign financing.

Table 3. Expenditures of 2022 Presidential Candidates (PHP)

|

Name |

Out of Personal Funds |

Out of Cash Contributions |

Out of in-kind Contributions |

Total Expenditures |

|

Marcos, Ferdinand Jr. |

0 |

371,795,857 |

251,434,320 |

623,230,177 |

|

Robredo, Leni |

19,779 |

388,327,500 |

0 |

388,347,279 |

|

Domagoso, Isko Moreno |

1,126,999 |

241,500,000 |

0 |

242,626,999 |

|

Lacson, Ping |

0 |

70,763,817 |

89,538,500 |

160,302,317 |

|

Pacquiao, Manny Pacman |

62,677,926 |

7,750,000 |

48,700,988 |

119,128,914 |

|

De Guzman, Leody |

0 |

1,000,203 |

0 |

1,000,203 |

|

Montemayor, Jose |

100,000.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

100,000.00 |

Note: Candidates Ernesto Abella, Norberto Gonzales, and Faisal Mangondato failed to file their Statement of Contribution and Expenditures before the June 9, 2022 deadline.

Table 4. Expenditures of 2022 Vice-Presidential Candidates (PHP)

|

Name |

Out of Personal Funds |

Out of Cash Contributions |

Out of in-kind Contributions |

Total Expenditures |

|

Duterte, Sara |

0 |

0 |

216,190,935 |

216,190,935 |

|

Sotto, Vicente III |

49,391,478 |

30,000,000 |

77,763,832 |

157,155,310 |

|

Pangilinan, Kiko |

21,096,601 |

109,520,000 |

0 |

130,616,601 |

|

Lopez, Manny SD |

1,069,349 |

600,000 |

140,000 |

1,809,349 |

|

Ong, Doc Willie |

522,257 |

0 |

0 |

522,257 |

|

Atienza, Lito |

240,807 |

0 |

0 |

240,807 |

|

Serapio, Carlos |

218,370 |

0 |

0 |

218,370 |

|

Bello, Walden |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Note: Candidate Rizalito David failed to file a Statement of Contribution and Expenditures before the June 9, 2022 deadline.

Third, The Philippines’ electoral systеm, primarily based on a mixed electoral method combining first-past-the-post and proportional representation elements, aims to balance majority rule and minority rights. Related legislation on party-list organizations[5] is supposed to facilitate a transition to proportional representation while opening an expanding venue for marginalized groups. Section 2 of R.A. 7941 or the Party-List Systеm Act[6] states that:

The State shall promote proportional representation in the election of representatives to the House of Representatives through a party-list systеm of registered national, regional and sectoral parties or organizations or coalitions thereof, which will enable Filipino citizens belonging to the marginalized and underrepresented sectors, organizations and parties, and who lack well-defined political constituencies but who could contribute to the formulation and enactment of appropriate legislation that will benefit the nation as a whole, to become members of the House of Representatives. Towards this end, the State shall develop and guarantee a full, free and open party systеm in order to attain the broadest possible representation of party, sectoral or group interests in the House of Representatives by enhancing their chances to compete for and win seats in the legislature, and shall provide the simplest scheme possible.

For Bernas (2009), appropriate limits must be placed on defining marginalized and underrepresented sectors in order to ensure that it will not indiscriminately include questionable organizations. Although Section 5 of the Party-List Systеm Act lists down considered sectors, namely labor, peasant, fisherfolk, urban poor, indigenous cultural communities, elderly, handicapped, women, youth, veterans, overseas workers, and professionals, Section 3 of R.A. 7941 opens it to other forms of organizations, namely national and regional parties,[7] while leaving the determination of individual representatives to their respective organizations. The latter opens the systеm to arrangements where an individual representative is not from the sector that he/she represents.

During the 2022 Elections, a total of 178 party-list groups ran for office. Table 5 below shows a list of the winners, indicating that 56 party-list organizations occupy 63 seats in the House of Representatives, facing 316 district representatives. Beyond mere numbers, Rodan (2018, 118) states that “entrenched elite privilege in the Philippines has continually triumphed over reform elements in the struggle over democratic representation via a PLS [Party-list Systеm], principally by promoting particularist ideologies of representation and institutionalizing political fragmentation.” Sectoral representatives, who are supposed to be the dominant type in a party-list systеm as a means of catering to marginalized groups, must contend with regional representatives who, at least formally, are pushing for the welfare of a respective ethnolinguistic or regional group (cf. Bueza 2022). To an extent, such representatives can be considered redundant to district representatives.

Moreover, as Rodan (ibid.) notes, the development of party-list representation is characterized by the entrenchment of elite interests and the weakness of progressive and left-leaning groups. The leading party-list organization during the 2022 elections was the ACT-CIS, led by Erwin Tulfo, a long-standing TV personality and the brother of incumbent Senator Raffy Tulfo, himself a TV personality. For the latter, the weakness of left-leaning and progressive groups was evident in 2022 when prominent party-list members of the Makabayan Bloc (Makabayang Koalisyon ng Mamamayan or Patriotic Coalition of the People) lost their long-held seats in the House of Representatives.

Table 5. Partial List of Elected Party-List Groups (House of Representatives)

|

Name |

Votes |

Seats |

|

ACT-CIS Partylist (Anti-Crime and Terrorism Community Involvement and Support Partylist) |

2,111,091 |

3 |

|

1-RIDER PARTYLIST (Ang Buklod ng mga Motorista ng Pilipinas) |

1,001,243 |

2 |

|

TINGOG (Tingog Sinirangan) |

886,959 |

2 |

|

4Ps (PAGTIBAYIN AT PALAGUIN ANG PANGKABUHAYANG PILIPINO) |

848,237 |

2 |

|

AKO BICOL (Ako Bicol Political Party) |

816,445 |

2 |

|

SAGIP (Social Amelioration & Genuine Intervention on Poverty) |

780,456 |

2 |

|

ANG PROBINSYANO |

714,634 |

1 |

|

USWAG ILONGGO PARTY |

689,607 |

1 |

|

TUTOK TO WIN |

685,587 |

1 |

|

CIBAC (Citizens’ Battle Against Corruption) |

637,044 |

1 |

|

SENIOR CITIZENS PARTYLIST (Coalition of Associations of Senior Citizens in the Philippines, INC.) |

614,671 |

1 |

|

DUTERTE YOUTH |

602,196 |

1 |

|

AGIMAT (Agimat ng Masa) |

586,909 |

1 |

|

KABATAAN (Kabataan Partylist) |

536,690 |

1 |

Bionat (2021) asserts that the party-list systеm remains rife with problems that can threaten the representative function of party-list organizations. The 20% cap in the allotment of seats in the House of Representatives and the formula used to give a maximum of 3 seats per party-list group prevents the expansion of proportional representation in the House of Representatives. Overall, the party-list systеm is a manifestation of severe limitations in the design of democratic representation in the country.

Current reform efforts embodied in Senate Bill No. 179 (An Act Providing For The New Omnibus Election Code Of 2022) gravitate around bringing the OEC in line with recent developments and persistent problems ranging from the rise of online campaigns to the issue of party-list representation and absentee voting (Revised Omnibus Election Code 2022; Tulad 2022). According to its explanatory and introductory note, Senate Bill No. 179 is meant to consolidate previous electoral laws to address:

the weaknesses of the automated election systеms and the greater need for more transparency require the adoption of a hybrid systеm. Also, the rampant abuses of the party-list systеm necessitate an overhaul of its implementation. In addition, the need to ensure that senior citizens, persons with disabilities, pregnant women, indigenous peoples, and internally displaced persons are given ample opportunity to cast their votes calls for the expansion of local absentee voting and the institutionalization of the emergency accessible polling places. Finally, the rise of a new avenue for political campaigns— the use of the internet and social media—requires the institution of contemporary measures in the areas of campaign propaganda and campaign finance. [authors’ italics]

The structures of representative politics in the Philippines breed a limited systеm of accountability that caters to sustaining the rule of elites rather than holding policy-makers responsible to their constituents. Two persistent issues come to mind, namely, political dynasties and party-switching. Both are key features of the Philippines’ defective systеm characterized by the prevalence of personalistic over policy-oriented modes of electoral campaigning and the underrepresentation of marginalized groups in decision-making bodies.

Political parties in the Philippines often show weak ideological coherence and are seen as vehicles for individual political ambitions rather than institutions for shaping public policy and aggregating interests. Mendoza et al. (2014) show that from 1987 to 2010, party-switching in the House of Representatives was at an average of 33.49%.[8] Moreover, between 2004 and 2013, the share of turncoats in the House of Representatives increased by 20% to 45%. These trends contribute to the constant formation of super-majorities in the House of Representatives that are commonly under the umbrella of the incumbent adm?nistration.

The prominence of political dynasties marks the concentration of power and wealth in certain areas of the Philippines. Due to the absence of implementing legislation on the anti-political dynasty provisions of the 1987 Constitution, fat dynasties (i.e., families with two or more members in elected office) have continued at both the national and local levels (Mendoza and Banaag 2017; Mendoza et al. 2019a, 2019b). Mendoza et al. (2019b, 3) states that:

Covering all local positions, the percentage of fat dynasties has increased from 19% in 1988 to 29% in 2017, growing at about 1%, or around 170 positions, per election period. In 2001, there were 1303 political clans with 2 family members, 257 political clans with 3 family members, and 157 political clans with 4 or more family members. These numbers have risen to 1443, 335 and 189, respectively, in 2010, and to 1548, 339, and 217, respectively in 2019.

Dynastic politics remain a prominent feature of Philippine politics. This study considers the impact of such oligarchic structures on vertical accountability, namely, the concentration of power and wealth in the hands of fewer and fewer people. Moreover, concerning a weak political party systеm, the process of democratic backsliding, characterized by executive aggrandizement, was reflected in a series of actions that undermined the independence of state and societal institutions during the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte. Through a super-majority coalition following the 2016 national elections, the executive encroached on the powers of the co-equal branches of government and stymied the exercise of media freedom. The PDP-Laban (Partido Demokratiko Pilipino–Lakas ng Bayan) led the coalition, the party of the executive, together with the Nacionalista Party, National People’s Coalition, National Unity Party, Lakas-CMD (Lakas–Christian Muslim Democrats), and various party-list organizations. Ironically, the bulk of the elected representatives from the Liberal Party, the former adm?nistration party, joined the majority instead of the minority bloc. The upper chamber had a similar realignment, with the parties identified with the adm?nistration forming a majority bloc to support the president’s legislative agenda (Magno and Teehankee 2022).

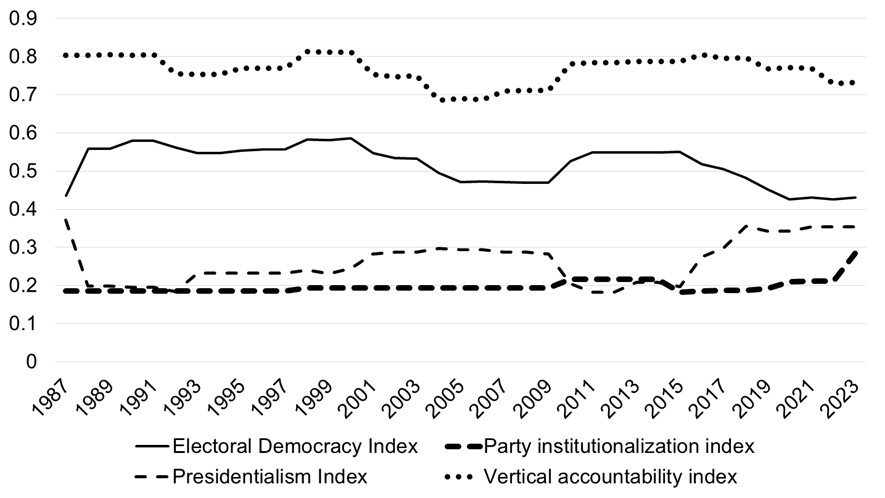

In Figure 1 below, the database Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) (Coppedge et al. 2023) shows that the vertical accountability index of the Philippines registered an average of 0.76 from 1986 to 2023 (post-EDSA period). On a scale from low to high (0-1), this index measures electoral accountability (i.e., the quality of elections, enfranchisement, and direct election of the chief executive) and the general quality of political parties (i.e., barriers to party formation and the autonomy of parties from the ruling regime).

This result is juxtaposed with the following, first of which is the party institutionalization index that measures the following aspects of the incumbent political party systеm: (1) party organization, (2) linkages with civil society, (3) the presence of distinct party platforms, and (4) party cohesion within an elected legislature. The Philippines holds an average score of 0.19 – a low and sustained score that reflects the weakness of political parties in the Philippines. Second is the electoral democracy index, measuring the quality of both elections and political freedoms between elections (e.g., freedom of the press and expression). The Philippines scores an average of 0.51 after experiencing a decrease from 2015 to 2022. Lastly is the presidentialism index, which measures the systеmic concentration of political power in the hands of one individual at the expense of delegation. The point estimates for this index have been reversed such that the directionality is opposite to the input variables. Lower scores indicate less presidentialist tendencies and vice versa.[9] The Philippines holds an average of 0.27 after experiencing a gradual increase from 2015 to 2023.

Figure 1. Varieties of Democracy Indices

These scores suggest that while Philippine politics enjoy a vibrant electoral systеm, it is founded more on individual leaders than party politics. It also shows that presidentialism, though muted compared to the authoritarian period under Ferdinand Marcos Sr., remains a threat given the above considerations on super-majorities in the House of Representatives. The succeeding sections flesh out vertical accountability from a psycho-political perspective, first in terms of citizen-leader relations and second with the issue of demand for accountability vis-à-vis values and attitudes towards political parties.

3. Citizen-Leader Relations and a Weak Demand for Accountability

Most Filipinos are keen on voting. Data from Table 6 shows as much through sustained voter turnout levels that are way above the 50% mark. Alongside this collective habit of regularly going to the polls is the vibrant and dramatic spectacle of Filipino electoral politics characterized by a myriad of events ranging from mass rallies, dancing politicians, and celebrity endorsements to more malevolent situations like election-related violence and fraud. Beneath all this, the Filipino political psyche begs analysis of what lies behind a person’s vote – what the values and attitudes that form the basis of electoral behavior are among Filipinos. Though this study will not provide an exhaustive account of this issue, it contributes to ongoing analyses of political values and attitudes among Filipinos.

Table 6. Voter Turnout Rates in the Philippines (1987 to 2022)

|

Election Year |

Voter Turnout (%) |

Total vote |

Registration |

VAP Turnout (%) |

Voting age population (VAP) |

|

2022 |

83.83 |

55,114,084 |

65,745,512 |

78.7 |

70,026,672 |

|

2019 |

74.31 |

47,296,442 |

63,643,263 |

71.91 |

65,771,984 |

|

2016 |

81.95 |

44,549,212 |

54,363,844 |

72.17 |

61,728,990 |

|

2010 |

74.98 |

38,162,985 |

50,896,164 |

69.93 |

54,574,173 |

|

2007 |

63.68 |

28,945,710 |

45,453,236 |

54.87 |

52,752,550 |

|

2004 |

76.97 |

33,510,092 |

43,536,028 |

68.77 |

48,727,136 |

|

2001 |

81.08 |

27,709,510 |

34,176,376 |

64.75 |

42,795,056 |

|

1998 |

78.75 |

26,902,536 |

34,163,465 |

66.78 |

40,287,296 |

|

1995 |

70.68 |

25,736,505 |

36,415,154 |

68.35 |

37,652,450 |

|

1992 |

70.56 |

22,654,194 |

32,105,782 |

65.29 |

34,699,860 |

|

1987 |

90 |

23,760,000 |

26,400,000 |

78.16 |

30,398,680 |

Source: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance Database

https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/advanced-search?tid=293

The question of citizen-leader relations is a fundamental aspect of representative democracy. The manner in which citizens perceive their relationship with leaders, the interactions between the represented and representatives, and the expectations of ordinary citizens regarding the role of elected officials as representatives of the public good are fundamental aspects that shape the dynamics and activities of elites within such a systеm (cf. Dovi 2012). Schmitter (2015, 36) sums it up as a two-way systеm, wherein citizens “with equal political rights and obligations have at their disposal regular and reliable means to access information, demand justification, and apply sanctions on their rulers,” who in turn can enjoy political legitimacy and a level of support despite criticisms from the general public.

Tied with a Schumpeterian interpretation of democracy as a process of political elites circulating through competitive elections, the issue of citizen-leader relations can be seen as intimately tied with that of electoral accountability. Ashworth (2012) posits that electoral accountability can be construed as a systеm of rewards and punishments that can ensure policymakers remain responsive to the will and welfare of their constituents. In essence, it is a congruence between the interests and conduct of policymakers and their constituents (cf. Hellwig and Samuels 2008).

Despite the ideals that underpin such a schema, the circulation of elites can result in the consolidation of power in the hands of a few if conditions become disempowering for the ordinary citizen (Borja 2015, 2017). In other words, electoral accountability can collapse under the weight of power asymmetry. Consequently, such a vicious cycle can result in a democratic crisis driven by the disempowerment of the ruled and a lack of obligations and accountability among rulers (Stoker 2006; Stoker and Evans 2014; Schmitter 2015).

Regarding the psycho-political tendencies underlying the struggle for vertical accountability, we note that many Filipinos exhibit illiberal tendencies toward leaders and incumbent institutions (Borja 2023). Table 7 below shows that from the Asia Barometer Survey (ABS)[10] (N=1200, Margin of Error ±3), many are willing to give absolute power to those they deem as “morally upright” despite supporting the sustenance of incumbent institutions for political representation, at least before the end of the EDSA regime and the rise Rodrigo Duterte and Ferdinand Marcos Jr. to the presidency.

Table 7. Values on Citizen-Leader Relations I (Asia Barometer Survey) (Percentage)

|

Wave |

3 (2010) |

4 (2014) |

5 (2018-19) |

|

If we have political leaders who are morally upright, we can let them decide everything. |

|||

|

Strongly Agree |

22.4 |

24.2 |

29.7 |

|

Agree |

37.3 |

38.7 |

34.3 |

|

Disagree |

27.9 |

24.9 |

8.2 |

|

Strongly Disagree |

11.9 |

11.9 |

5.0 |

|

Government leaders are like the head of a family; we should all follow their decisions. |

|||

|

Strongly Agree |

14.6 |

14.7 |

31.2 |

|

Agree |

25.4 |

32.2 |

36.9 |

|

Disagree |

36.0 |

35.5 |

11.7 |

|

Strongly Disagree |

23.4 |

17.1 |

7.1 |

|

We should get rid of parliament and elections and have a strong leader decide things. |

|||

|

Strongly Agree |

10.7 |

9.9 |

15.7 |

|

Agree |

23.7 |

23.0 |

25.8 |

|

Disagree |

27.9 |

32.2 |

12.8 |

|

Strongly Disagree |

36.5 |

34.2 |

20.7 |

|

The army (military) should come in to govern the country. |

|||

|

Strongly Agree |

7.9 |

8.1 |

20.3 |

|

Agree |

16.1 |

20.2 |

34.2 |

|

Disagree |

30.9 |

30.0 |

11.4 |

|

Strongly Disagree |

44.2 |

40.7 |

15.9 |

|

We should get rid of elections and parliaments and have experts make decisions on behalf of the people. |

|||

|

Strongly Agree |

5.3 |

3.9 |

14.3 |

|

Agree |

12.1 |

13.7 |

30.4 |

|

Disagree |

28.6 |

32.1 |

13.9 |

|

Strongly Disagree |

53.0 |

49.7 |

16.1 |

Table 8 shows that many citizens see government leaders more as autonomous trustees who can identify and pursue the interests of their constituents. They also consider the government more as a parent who can decide on what is “good” for the public instead of being an employee. To flesh out the latter, wave 5 of the ABS pins down the issue of accountability. It asks respondents whether it is more important for citizens to hold the government accountable, even if that means it makes decisions more slowly or vice versa in favor of decisiveness at the expense of accountability. Most of the respondents from the Philippines (53.1%) favor decisiveness over accountability. Nonetheless, many Filipinos see political legitimacy as something based on open and competitive elections rather than virtue and capability sans electoral competition. However, this experienced a turn during the last wave. The appeal of strongman politics is juxtaposed with a warped understanding of representation and electoral legitimacy from these observations. We can see the psycho-political foundations of electoral politics in the Philippines as almost Caesarist in its orientation – leader-centric at the expense of incumbent liberal institutions.

Table 8. Values on Citizen-Leader Relations II (Asia Barometer Survey) (Percentage)

|

Wave |

3 (2010) |

4 (2014) |

5 (2018-19) |

|

Leaders as Delegates or Trustees |

|||

|

Leaders as Delegates (Government leaders implement what voters want.) |

33.7 |

34.9 |

25.6 |

|

Leaders as Trustees (Government leaders do what they think is best for the people.) |

64.9 |

63.7 |

72.7 |

|

Government as an Employee or a Parent |

|||

|

Government as an Employee (Government is our employee, the people should tell government what needs to be done.) |

44.3 |

44.1 |

|

|

Government as a Parent (The government is like parent; it should decide what is good for us.) |

54.5 |

55.0 |

|

|

Government Accountability and Decisiveness |

|||

|

Accountability over Decisiveness (It is more important for citizens to be able to hold government accountable, even if that means it makes decisions more slowly.) |

|

|

41.7 |

|

Decisiveness over Accountability (It is more important to have a government that can get things done, even if we have no influence over what it does.) |

|

|

56.3 |

|

Legitimacy through Elections or Personal Attributes |

|||

|

Legitimacy through Elections (Political leaders are chosen by the people through open and competitive elections.) |

67.7 |

63.8 |

50.3 |

|

Legitimacy through Virtue and Capacity (Political leaders are chosen on the basis on their virtue and capability even without election.) |

31.4 |

35.4 |

47.9 |

Data from V-Dem echoes the observations above on two accounts. First, the Philippines also scores low on the participatory democracy index with an average of 0.35. This suggests that political participation is largely confined to the electoral process. The recent study by Borja, Torneo, and Hecita (2024) provides further insight into this phenomenon, illustrating how for many Filipinos, political participation is largely confined to the ballot. Following the casting of their votes, most individuals return to silence as spectators to a politics that they deem as beyond their capacity to control or comprehend.

Lastly, in relation to the value ascribed to the person of the president (whether they are imbuing the leader with extraordinary characteristics and abilities), the Philippines exhibits a relatively low score of 1.99 on a scale of 1 to 4 (low to high). However, there was a notable increase from 2016 to 2021, with the current value exceeding 2.0 at 2.32. The 2016 spike reflects the impact of Rodrigo Duterte’s populism on pre-existing leader-centric tendencies among Filipinos (Borja 2023). The mythos constructed around him as a strongman exacerbated the emphasis on the individual leaders tied with fanaticism among supporters) of representative politics in the Philippines.

Furthermore, the spike did not revert to pre-Duterte levels due to two possible factors. The Duterte family continues to exert influence in the political sphere, with Rodrigo Duterte, his daughter Vice President Sara Duterte and son Davao City Mayor Sebastian Duterte, representing the family’s distinct leadership style. Conversely, incumbent President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. embodies the long shadow cast by the authoritarian legacy of his father and namesake – the shadow of a unifying and strong-handed form of leadership (Teehankee 2023).

How might these seemingly contradictory tendencies surrounding the issue of vertical accountability be made sense of? To address this, it is important to note that expectations play a crucial role in generating demand for electoral accountability. Nonetheless, expectations are not isolated phenomena; they are shaped by multitude of cognitive factors. Such attitudes can in turn shape the evaluation of the entire political systеm (Svolik 2013). A consequence of repeated exposure to the corrupt and abusive practices of policymakers is that citizen-voters may come to perceive all politicians as corrupt. Consequently, this can lead to a pervasive pessimism over government, which in turn can facilitate the establishment of lower barriers for actual crooks.

From Svolik’s (2013) insights on the matter, we identify two general concerns: the structural and psycho-political factors that shape expectations and the barriers that constitute electoral accountability. When considered collectively, the question arises as to whether citizen-voters can effectively (i.e., they desire it and there are institutional arrangements that accommodate such a demand) impose costs and disincentives on elected officials through the ballot. As we will demonstrate, the challenge to electoral accountability in the Philippines can be construed as a vicious cycle of weak institutions and a lack of demand from ordinary citizen-voters.

Overall, the structure of Filipino politics and the political values held by citizen-voters have rendered the systеm incapable of generating a demand for electoral accountability. From the perspective of cycles and habits, it can be argued that this condition is self-perpetuating, creating a vicious cycle that renders political accountability a non-issue for many Filipinos, including both citizen-voters and policymakers. How can such a cycle be broken? This essay concludes with a general assessment of political parties in relation to citizen engagement and government accountability before elaborating on certain directions for reform.

4. Assessment: On Political Parties, Citizen Engagement, and Government Accountability

Political parties are intended to aggregate interests and serve as a bridge between the government and the citizens. However, internal fragmentation and a lack of genuine policy-based competition frequently undermine their effectiveness. Regarding dynastic and oligarchic politics, it also appears that party politics are only secondary to these two other forms, primarily serving as formal vehicles for particular interests.

Much has been said about the impacts of a weak political party systеm and dynastic politics on vertical accountability and democratization (see Arugay 2005; Caritos and Yadao 2024; Hutchcroft 2020; Hutchcroft and Rocamora 2012; Kasuya and Teehankee 2020; Maambong 2001; Mendoza and Banaag 2017; Mendoza et al. 2019a, 2019b; Rivera 2016; Rodan 2018; Teehankee and Calimbahin 2020). Nonetheless, this study notes a recent examination by Aguirre (2023) as a means of providing a brief overview of party-movement dynamics. In looking at the post-authoritarian regime, Aguirre (ibid.) illustrates that the relationship between political parties and social movements is characterized by a dance of contention, cooperation, and even cooptation. How this dance plays out eventually affects the trajectory of democratization (e.g., in terms of inclusion, the expansion of rights, redistribution of wealth and power, etc.). In more specific terms and echoing previous works on party politics and patronage in the Philipines, Aguirre (ibid., 171) states that the dynamics between social movements and political parties are affected by:

a) dominance of political dynasties, especially with its exclusive access to wealth and power; b) clientelistic-patronage relations with its systеmic and uninterrupted flow of resources to networks of control; c) malleability of the middle class and its newfound worth and importance that makes this class autonomous and believe that it is capable of producing its own class of leaders; and d) unresolved tensions among the Left movements that continue to cripple any effort for a concerted move to push for substantial and long-term reforms in the society.

In summary, party politics in the Philippines gravitate around the concentration of power and the prominence of patronage and money politics as obstacles to expanding and developing vertical accountability. The sheer lack of political party institutionalization renders internal party politics a game for party elites, with ordinary citizens being reduced into mobilized entities. One thing is for sure: sophisticated party political functions (e.g., party conventions) like those found in the United States and the West are either rare or non-existent among Philippine political parties.

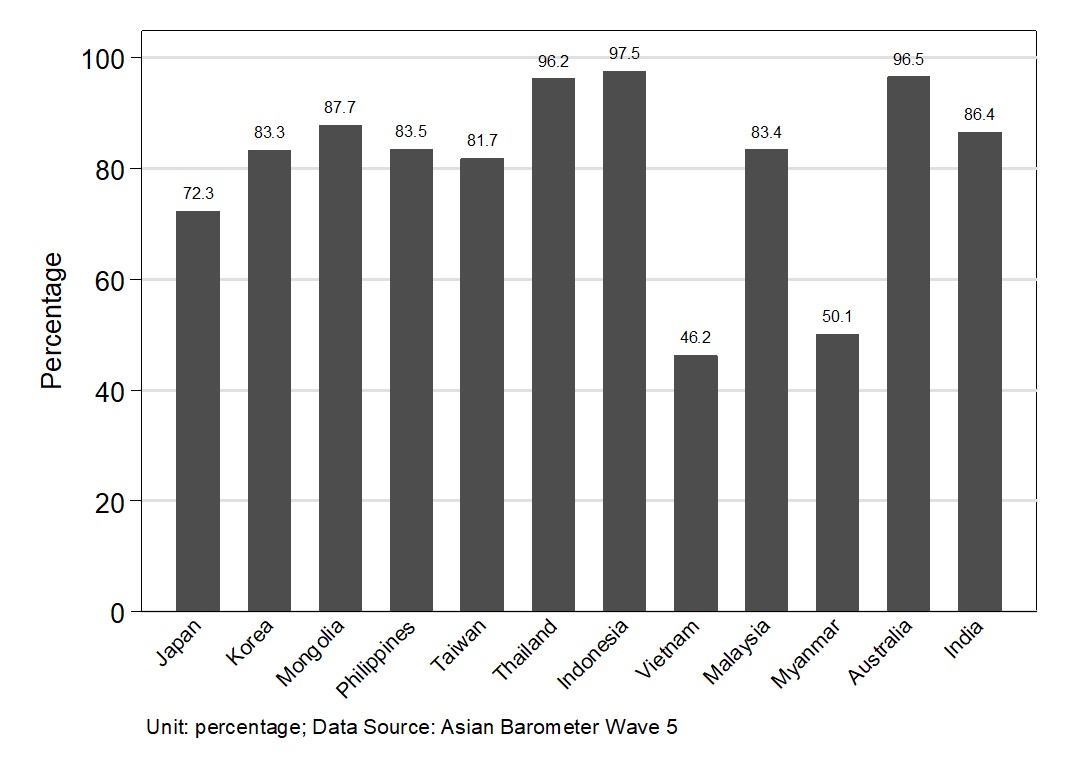

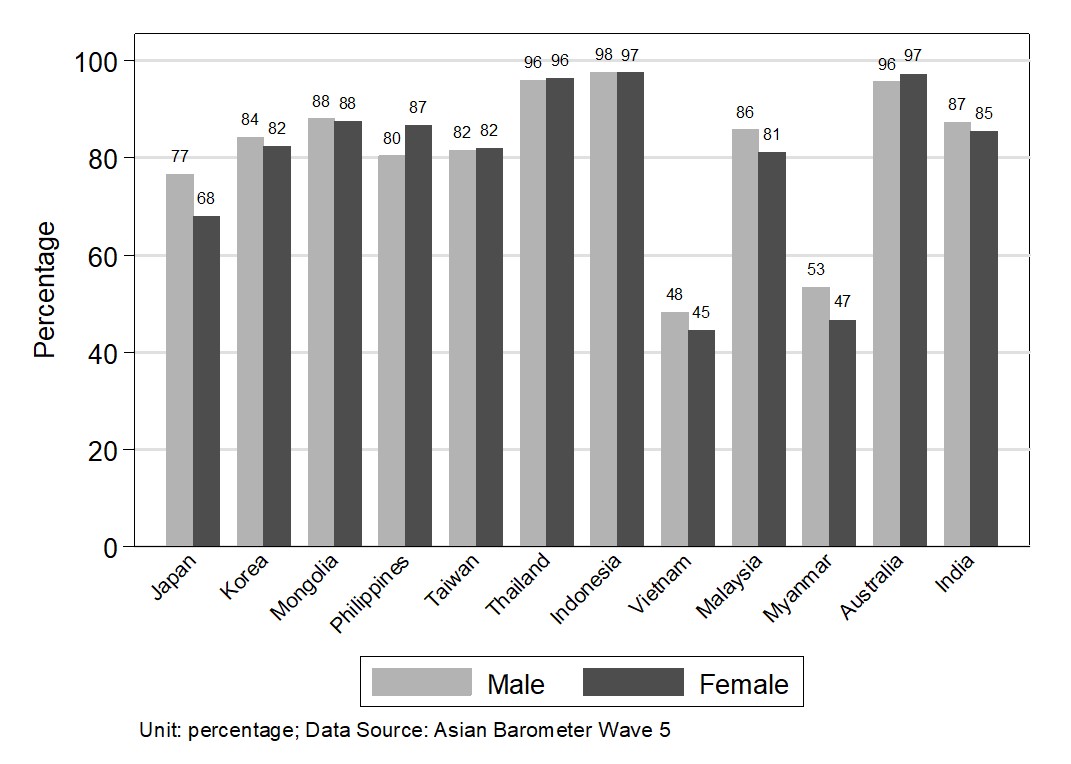

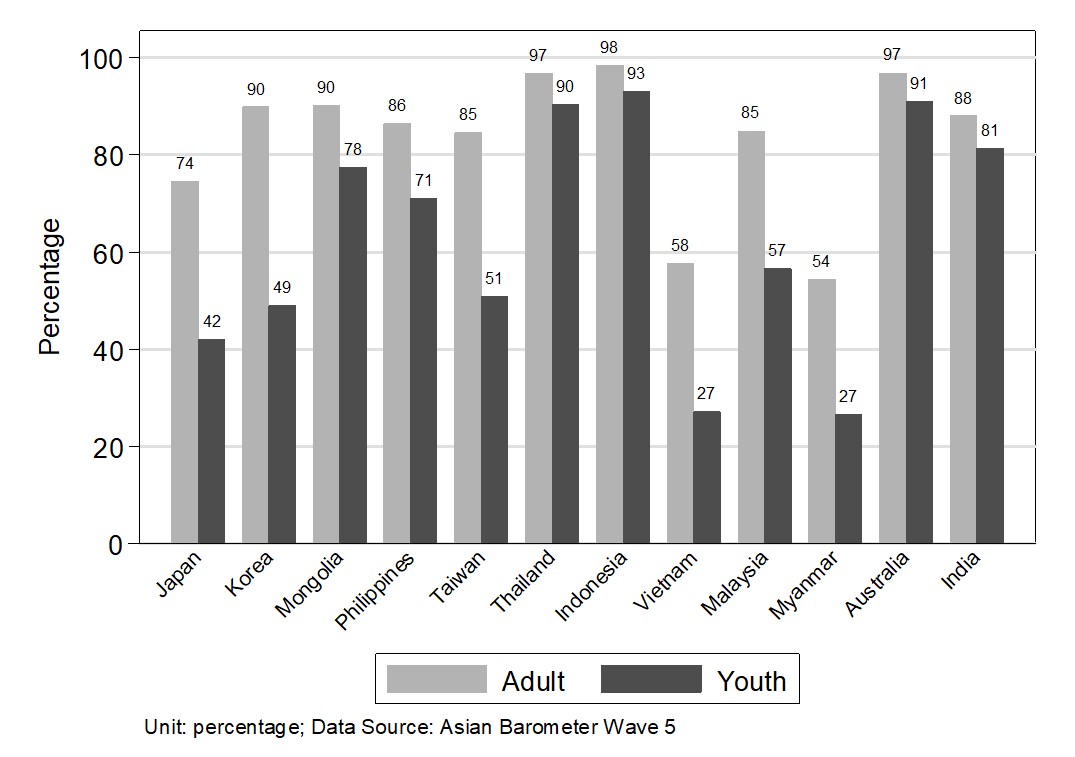

Thus, this section looks at the issue from a psycho-political perspective. Specifically, this section assesses the Filipino political party systеm concerning how citizens relate to political parties and in comparison to other multi-party systеms in Southeast Asia, namely, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. This study notes the following sampling considerations listed in Table 9 below.

Table 9. Sampling and Margins of Error

|

Wave |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|||

|

|

Sample size |

Margin of error |

Sample size |

Margin of error |

Sample size |

Margin of error |

|

Philippines |

1,200 |

± 3% |

1,200 |

± 3% |

1,200 |

± 3% |

|

Thailand |

1,512 |

± 2% |

1,200 |

± 3% |

1,200 |

± 3% |

|

Indonesia |

1,550 |

± 2.5 % |

1,550 |

± 2.5 % |

1,540 |

± 2.5% |

|

Malaysia |

1,214 |

± 3% |

1,206 |

± 3% |

1,237 |

± 2.79% |

Note: The respective time frames of the 3rd, 4th, and 5th ABS waves are as follows: (1) Philippines (2010, 2014, 2018—19); (2) Thailand (2010, 2014, 2018—19); (3) Indonesia (2011, 2016, 2019); (4) Malaysia (2011, 2014, 2019).

Table 10 shows that most citizens in Indonesia and Malaysia have expressed consistent levels of distrust towards political parties. The contrary is true for those in the Philippines and Thailand. Despite such levels of trust, Table 11 below shows that party membership is low and decreasing in the case of the Philippines. Party membership is generally low for the four cases, but Malaysia experiences comparatively higher levels than its neighbors.

Table 10. Trust in Political Parties (Percentage)

|

|

Philippines |

Thailand |

||||

|

Wave |

3 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

Trust |

35.8 |

31.9 |

68.0 |

35.5 |

38.6 |

54.6 |

|

Distrust |

62.5 |

65.9 |

29.0 |

49.6 |

51.9 |

35.5 |

|

|

Indonesia |

Malaysia |

||||

|

Wave |

3 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

|

Trust |

42.1 |

39.2 |

42.1 |

39.2 |

42.1 |

39.2 |

|

Distrust |

48.3 |

51.5 |

48.3 |

51.5 |

48.3 |

51.5 |

Table 11. Party Membership (Percentage)

|

Wave |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

Philippines |

1.6 |

1.8 |

0.8 |

|

Thailand |

0.6 |

1.8 |

0.1 |

|

Indonesia |

4.4 |

2.1 |

2.7 |

|

Malaysia |

10.3 |

6.3 |

10.4 |

Table 12 below shows some additional measurements of partisanship in terms of active expressions of support and feelings of proximity to specific political parties. This study observes general inaction in electoral partisan activities, especially in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Concerning party affinity, most of the respondents from Malaysia and, to an extent, the Philippines have expressed positive attitudes. The contrary is true for respondents from Indonesia and Thailand. Among those who felt close to a political party, more respondents from Malaysia expressed higher levels of proximity than those from the Philippines, Indonesia, and Thailand. This study leaves the meaning of “feeling close” to parties for future and more qualitative inquiries. What can be noted is that for the Philippines, association with political parties is not aligned with either membership or participation in party activities. Given the high levels of voter turnout, it is plausible that party association among ordinary Filipinos is only enough to make citizens go to the ballot.

Table 12. Party Association in Multi-Party Systеms (Percentage)

|

|

Philippines |

Thailand |

||||

|

Wave |

3 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

Q: Attend a campaign meeting or rally* |

||||||

|

Yes |

20.4 |

18.9 |

17.0 |

53.8 |

39.2 |

33.4 |

|

No |

66.4 |

80.6 |

82.2 |

44.7 |

55.3 |

62.1 |

|

Q: Try to persuade others to vote for a certain candidate or party* |

||||||

|

Yes |

18.5 |

21.6 |

23.0 |

23.1 |

17.4 |

11.3 |

|

No |

68.2 |

77.8 |

76.3 |

74.3 |

75.9 |

82.6 |

|

Q: Did you do anything else to help out or work for a party or candidate running in the election?* |

||||||

|

Yes |

15.6 |

14.6 |

16.7 |

11.7 |

8.5 |

3.5 |

|

No |

71.3 |

84.8 |

82.8 |

84.8 |

85.0 |

90.4 |

|

Q: Among the political parties listed here, which party if any do you feel closest to? |

||||||

|

Do not feel close to any political party |

46.9 |

41.0 |

39.2 |

60.5 |

70.8 |

65.3 |

|

Q: How close do you feel to (Specific Political Party)? ** |

||||||

|

Very close |

13.6 |

16.3 |

15.0 |

14.9 |

8.0 |

7.1 |

|

Somewhat close |

40.7 |

50.5 |

44.3 |

31.5 |

31.7 |

24.8 |

|

Just a little close |

45.7 |

33.2 |

40.7 |

53.5 |

60.3 |

68.0 |

|

|

Indonesia |

Malaysia |

||||

|

Wave |

3 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

Q: Attend a campaign meeting or rally* |

||||||

|

Yes |

26.2 |

15.74 |

8.4 |

31.5 |

31.8 |

31.6 |

|

No |

71.7 |

81.81 |

90.6 |

67.8 |

67.8 |

68.4 |

|

Q: Try to persuade others to vote for a certain candidate or party* |

||||||

|

Yes |

18.7 |

13.4 |

9.4 |

15.4 |

16.9 |

17.1 |

|

No |

80.1 |

85.2 |

89.5 |

83.5 |

82.7 |

82.8 |

|

Q: Did you do anything else to help out or work for a party or candidate running in the election?* |

||||||

|

Yes |

11.3 |

8.8 |

6.8 |

19.9 |

20.5 |

19.8 |

|

No |

87.1 |

89.7 |

92.6 |

79.1 |

79.0 |

80.1 |

|

Q: Among the political parties listed here, which party if any do you feel closest to? |

||||||

|

Do not feel close to any political party |

|

79.7 |

84.8 |

10.7 |

9.0 |

41.1 |

|

Q: How close do you feel to (Specific Political Party)? ** |

||||||

|

Very close |

11.3 |

9.5 |

11.5 |

38.3 |

32.2 |

29.1 |

|

Somewhat close |

46.3 |

53.7 |

39.6 |

44.6 |

45.3 |

49.0 |

|

Just a little close |

42.4 |

36.7 |

49.0 |

17.1 |

22.5 |

21.9 |

Notes:

* These questions were asked in the context of a national election.

** This study did not focus on specific parties and will leave this matter for future inquiries.

Concerning their values toward the political party systеm, this study notes that when asked about their preference for a multi-party or single-party systеm, Table 13 shows a general aversion towards a single-party systеm. However, there are certain nuances to this general tendency, with the Philippines experiencing a growing preference for a single-party systеm. At the same time, the contrary is true for other multi-party systеms where there is an increasing aversion to the possibility of a single-party systеm.

Table 13. Political Party Systеm Preference in Multi-Party Systеms (Percentage)

|

Q: Only one political party should be allowed to stand for election and hold office. |

||||||

|

|

Philippines |

Thailand |

||||

|

Wave |

3 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

Strongly approve |

10.9 |

8.2 |

11.4 |

6.3 |

9.3 |

2.7 |

|

Somewhat approve |

20.6 |

21.3 |

29.7 |

12.2 |

21.6 |

11.3 |

|

Somewhat disapprove |

29.8 |

32.7 |

38.5 |

24.1 |

27.0 |

31.3 |

|

Strongly disapprove |

37.7 |

37.2 |

19.5 |

51.5 |

30.8 |

34.7 |

|

|

Indonesia |

Malaysia |

||||

|

Wave |

3 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

Strongly approve |

1.2 |

1.1 |

0.4 |

9.4 |

11.3 |

7.3 |

|

Somewhat approve |

14.7 |

8.9 |

6.8 |

16.5 |

15.7 |

15.6 |

|

Somewhat disapprove |

68.6 |

64.5 |

63.6 |

31.3 |

24.5 |

28.6 |

|

Strongly disapprove |

8.9 |

11.1 |

15.3 |

39.5 |

46.1 |

47.3 |

Overall, in line with the summary in Table 14 below, juxtaposed with certain contradictory tendencies between specific and general anti-party attitudes is a preference for strong elected leaders. What are the probable implications of this condition? For those under multi-party systеms who are distant from specific political parties, their qualified commitment to a multi-party systеm is probably due to their want of a strong leader. Specifically, their ideal is likely for a multi-party systеm to allow the coalescence of political parties under a strong leader, which gives an image of citizens tolerating a systеm populated by weak and indistinct political parties—party cartelization—that can produce “strong” leaders.

Table 14. Summary of Observations

|

|

Philippines |

Thailand |

Indonesia |

Malaysia |

|

Specific Political Party Support |

||||

|

Dis/Trust Towards Political Parties |

Distrust |

Distrust |

Distrust |

Trust |

|

Party Membership |

Decreasing |

Decreasing |

Decreasing |

Increasing |

|

Party Affinity |

Average and Decreasing |

Low and Decreasing |

Low and Decreasing |

High with steep Decrease3 |

|

Party Activism |

Low and Decreasing |

Low and Decreasing |

Low and Decreasing |

Low and Decreasing |

|

General Political Party Support |

||||

|

Support for One-Party Rule |

? Approval ? Disapproval |

? Disapproval ? Approval |

? Disapproval ? Approval |

? Disapproval - Approval |

|

One-party rule is essential to democracy |

Ambivalent |

Ambivalent |

Disapprove |

Ambivalent |

5. Areas for Reform

This study shows that alongside limitations in the electoral and political party systеms, there is a value systеm leaning more toward giving more license to leaders instead of holding them accountable as public servants in the Philippines. The nature of this problem requires a concerted effort to address both the supply and demand sides of vertical accountability. In other words, reform must be encompassing. It must strive to establish a fair, competitive, and substantially representative electoral systеm populated by strong and policy-oriented political and sectoral parties while enhancing demand for accountability by decreasing reliance on leaders and promises of goodwill from elected officials. To this end, this study recognizes the following areas for reform:

Institutional Mechanisms beyond Elections: Beyond periodic elections, several mechanisms must enable citizens to hold their government accountable, including the impeachment process, public consultations, increased civic activism, and the media. The effectiveness and accessibility of these mechanisms are analyzed to understand their role in fostering a responsive and responsible government. Local participatory governance (e.g., participatory budgeting) is one key policy at the local level that facilitates the entry of constituents into the halls of local government, thus exposing elected officials to the scrutinizing gaze of ordinary citizens while allowing the latter to enjoy a greater share in public affairs. The Naga City case, which started during the term of Mayor Jesse M. Robredo, still stands as a model for participatory local governance in the Philippines. At the level of national electoral politics, the institutionalization of authentic debates among candidates, as well as town hall meetings and open conversations between them and ordinary citizens, could reduce the impact of one-way political marketing and increase the demand for candidates to clarify and concretize their stand on specific issues. Another possible area for development is promoting and developing plebiscitary mechanisms for vital local and national legislation. The case of Palawan, where ordinary citizens resisted efforts to split the province into three political jurisdictions, stands as an invaluable but rare occasion highlighting the value of plebiscites (Fabro 2021).

Strengthening Political Parties as Institutions of Representation: To enhance their function as effective democratic tools, Philippine political parties require significant reform. This section suggests specific measures such as enforcing party loyalty, strengthening policy-based platforms, enhancing internal democracy, and improving transparency and accountability mechanisms within parties. There is a need for the passage of a Political Party Development Act that would strengthen the political party systеm and build democratic institutions. To this end, House Bill No. 488 of the 19th Congress seeks to accomplish the following: (1) institutionalize reforms in campaign financing to promote accountability and transparency; (2) provide financial subsidies to political parties for the sake of campaigns and party development; (3) promote party loyalty and discipline; (4) support voter’s education and civic literacy programs through political parties. Despite its promises, House Bill No. 488 remains to be enacted as law. Reforms are also necessary to better align the Party-List systеm with the representation of marginalized sectors. However, there are recent attempts to use party-list systеm reform as a means to crack down on leftist organizations by tagging them as part of communist insurgencies. An example is Senate Bill No. 201, pursuant to the contested R.A. 11479 (the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020).

Necessary Political and Electoral Reforms: This study proposes comprehensive reforms aimed at improving the electoral systеm’s capacity to represent diverse voter interests and enhance political accountability. Recommendations include the introduction of anti-dynasty laws, campaign finance reform, electoral systеm adjustments to ensure more proportional representation, and enhanced regulatory oversight of party activities. The legislation of a Campaign Finance Reform Act would regulate campaign contributions and promote transparency in sources of funds and campaign expenditures, which is directed squarely at the structures of money politics for the sake of a more inclusive and fair electoral process wherein the sheer power of campaign financing will not hinder candidates who are outside prominent and powerful patronage networks. Moreover, strict regulations on candidate substitution should be in place, given the games of substitution played by prominent candidates during the 2022 National Elections have rendered the mechanism subject to abuse (Aning 2024; Torres 2024). Overall, electoral reforms must make the electoral process less vulnerable to the political and financial machinations of the ruling elites.

Enhancing Civic Education and Open Data Dashboards: There is a need to enhance civic education – for citizens to demand capacity, performance, and accountability from leaders. Knowledge partnerships can be forged to co-produce open data dashboards that show the performance of politicians and political parties, which would help citizens appreciate the use of data in making electoral choices. Building a deliberative democracy involves the pursuit of civic education and the development of knowledge intermediaries and policy think tanks to help citizens recognize the value of data and performance to guide them in holding leaders accountable (Magno 2022). There is a need to harness universities, policy think tanks, and other knowledge institutions to serve as information intermediaries to help citizen voters make sense of policy reports, technical data, budget documents, and audit reports to make performance evaluations of parties and groups offering to lead the country. Ongoing efforts like PARTICIPATE[11] can help bring electoral politics closer to citizen voters while exposing them to critical assessments of local and national politics. Moreover, civic education must be directed not only at ordinary citizens but also at party elites via regular efforts in bottom-up party development activities that can ensure, at most, the reform of old parties and, at least, the emergence of more policy-oriented and internal democratic parties.

In summary, these areas for reform have two main objectives. The first is to foster electoral and political party systеms that place accountability as a core principle by being less vulnerable to the impacts of money and dynastic politics. The second is to generate demand for accountability among ordinary citizens by making them less and less reliant on leaders – exorcising the shadow of messianic tendencies – through civic empowerment.

6. Conclusion: The Long Road Ahead

The ability of political parties and the electoral systеm to effectively represent and respond to the electorate in the Philippines is currently suboptimal. From a psycho-political perspective, the current systеm has failed to both sway citizens away from a reliance on leaders and to embrace the ideal of policy-oriented political parties, in terms of both association and actual participation in party activities. Strengthening these institutions through targeted reforms is essential for enhancing democratic governance and ensuring that government actions consistently reflect the will and interests of the people.

One can easily say that change does not happen overnight. However, such a dictum veils the reality that the relationship between structures and individual agency is shaped by the role of habits. In other words, the question of electoral accountability in the Philippines becomes a matter of disrupting the habits of policymakers and citizen-voters that devalue accountability itself. A great deal has been written about the possibility of reforming the political systеm in the Philippines, particularly in relation to the political party systеm. Proposals have been put forth to strengthen party discipline by imposing penalties for defections and encouraging parties to adapt a more programmatic approach to elections.

Moreover, mass-based parties continue to represent the gold standard for reformist efforts. Such a systеm can only function effectively if political parties can serve as a genuinely democratic conduit between ordinary citizens and the policy-making process. This democratic function must be twofold. Firstly, political parties must facilitate political participation outside of the electoral process. Such involvement need not be contingent upon formal party membership. Nonetheless, it is imperative that political parties are able to facilitate effective non-electoral modes of participation. Secondly, mass-based parties must ensure that representation is contingent upon accountability, rather than being based on idolatry or acquiescence. It is possible for a political party to be mass-based without being accountable. This can result in the formation of a mass movement that is dependent on the charismatic leadership of a single figure. This represents a potential future for party politics in the Philippines, given the sustained leader-centric tendencies among its citizens.

Consequently, addressing the issues of personality-centric and leader-centric politics, as well as the prevalence of patronage and clientelism in the Philippines, necessitates the development of a political party systеm that encompasses both leaders and citizens under the umbrella of a policy-oriented approach to electoral politics.

We endorse these calls and underscore the necessity of integrating accountability as a fundamental element of civic-political education in the Philippines. In light of Svolik’s (2013) insights on expectations, it is imperative that civic-political education in the Philippines be geared towards lifting the expectations of citizen-voters with regard to the ideal of electoral accountability. Nonetheless, such an approach necessitates the provision of exemplars; citizen-voters must observe and experience the possibility of holding elected officials to account in the periods preceding, during, and following elections. Thus, we return to the question of incumbent institutions, especially those concerned with justice. This gives rise to the question of rupture. If we consider vertical accountability deficit as a form of cycle, then it is important to determine at which points is this process more vulnerable and susceptible to reform. ■

References

19th Congress, Senate Bill no. 179 (An Act Providing For The New Omnibus Election Code Of 2022). (July 7, 2022). http://legacy.senate.gov.ph/lis/bill_res.aspx?congress=19&q=SBN-179 (Accessed May 20, 2024)

19th Congress, House Bill no. 488 (An Act Strengthening the Political Party Systеm and Appropriating Funds Therefor). (June 30, 2022). https://issuances-library.senate.gov.ph/bills/house-bill-no-488-19th-congress (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Aguirre, Arjan. 2023. “Party-Movement interactions in a contested democracy: The Philippine experience.” In J. C. Teehankee & C. Echle, Eds. Rethinking Parties in Democratizing Asia (1st ed., pp. 151–175). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003324478 (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Aning, Jerome. 2024. “Comelec to toughen rule on candidate substitution.” Inquirer.Net. May 4. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1936949/comelec-to-toughen-rule-on-candidate-substitution (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Arugay, Aries. 2005. “The accountability deficit in the Philippines: Implications and prospects for democratic consolidation.” Philippine Political Science Journal 26, 1: 63-88.

Ashworth, Scott. 2012. “Electoral accountability: Recent theoretical and empirical work.” Annual Review of Political Science 15: 183-201.

Bernas, Joaquin G. 2009. The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines: A Commentary. Quezon City: REX Book Store, Inc.

Bionat, Justin Francis. 2021. “The Philippine Party-list Systеm and Representation of Marginalized Populations.” WVSU Journal for Law Advocacy 1: 1-16.

Borja, Anthony Lawrence, Ador Torneo, and Ian Jayson Hecita. 2024. “Challenges to Democratization from the Perspective of Political Inaction: Insights into Political Disempowerment and Citizenship in the Philippines.” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1177/18681034241239060 (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Borja, Anthony Lawrence. 2015. “Re-conceptualising political alienation: On spectators, spectacles and public protests. Theoria 62, 144: 40-59.

______. 2017. “‘Tis but a Habit in an Unconsolidated Democracy: Habitual Voting, Political Alienation and Spectatorship.” Theoria 64, 150: 19-40.

______. 2023. “Political Illiberalism in the Philippines: Analyzing Illiberal Political Values.” Asia-Pacific Social Science Review 23, 1: 63-78.

Bueza, Michael. 2022. “20 winning party-list groups in 2022 got majority of votes from bailiwick regions.” Rappler. June 2. https://www.rappler.com/nation/elections/winning-party-list-groups-2022-vote-sources/ (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Caritos, Ona, and Alexa Yadao. 2024. Philippines. In B. Rosales, Ed. Asian Electoral Review: Advancing Electoral Democracy through Electoral Reforms (pp. 226-269). Bangkok: Asian Network for Free Elections.

Co, Edna, Jorge Tigno, Maria Lao, and Margarita Sayo. 2005. Philippine Democracy Assessment: Free and Fair Elections and the Democratic Role of Political Parties. Manila: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Commission on Elections. 2022. Party-list Summary of Statement of Votes by Region (By Rank). https://comelec.gov.ph/php-tpls-attachments/2022NLE/ElectionResults/2022NLE_PartyListSummaryStatementofVotes.pdf (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, et al. 2023. “V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v13” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds23 (Accessed May 20, 2024)

De Leon, Dwight. 2022. “TRACKER: Candidates who spent the most in 2022, based on their SOCEs.” Rappler. July 14. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/tracker-candidates-spent-most-statement-contributions-expenditures-2022/ (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Deschouwer, Kris. 1996. “Political Parties and Democracy: A Mutual Murder?” European Journal of Political Research 29, 3: 263-278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1996.tb00652.x (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Dovi, Suzanne. 2012. The Good Representative. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Publications.

Eusebio, Gerardo V. 2021. “Legislating Campaign Finance Reforms in the Philippines: Applying Lessons from Japan.” De La Salle University – La Salle Institute of Governance Policy Brief 2, 1: 1-9.

Fabro, Keith Anthony. 2021. “‘No’ votes win in Palawan plebiscite.” Rappler. March 16. https://www.rappler.com/nation/no-votes-win-palawan-plebiscite/ (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Hellwig, Timothy, and David Samuels. 2008. “Electoral accountability and the variety of democratic regimes.” British Journal of Political Science 38, 1: 65-90.

Hutchcroft, Paul, and Joel Rocamora. 2012. “Patronage-based parties and the democratic deficit in the Philippines: origins, evolution, and the imperatives of reform.” In R. Robison, Ed. Routledge Handbook of Southeast Asian Politics (pp. 97-119). New York: Routledge.

Hutchcroft, Paul, ed. 2020. Strong patronage, weak parties: The case for electoral systеm redesign in the Philippines. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co.

Kasuya, Yuko, and Julio Teehankee. 2020. “Duterte Presidency and the 2019 midterm election: An anarchy of parties?” Philippine Political Science Journal 41, 1-2: 106-126.

Katz, Richard S. 2006. “Party in Democratic Theory.” In Richard S. Katz and William J. Crotty, eds. Handbook of Party Politics (pp. 34-46). London: Sage.

La Salle Institute of Governance. 2022. “Revised Omnibus Election Code pushed to modernize PH polls.” October 3. https://www.dlsu-jrig.com/blog/policyforum04 (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Maambong, Regalado E. 2001 “The Philippine Law on Elections in Perspective.” Ateneo Law Journal 46: 436-446.

Magno, Francisco A. 2022. “Governance agenda for development in a post Covid-19 Philippines,” in Victor Andres Manhit, ed. Beyond the Crisis: A Strategic Agenda for the Next President (pp. 297-322). Makati: Stratbase ADRI.

Magno, Francisco A., and Julio C. Teehankee. 2022. “Pandemic politics in the Philippines: An introduction from the special issue editors.” Philippine Political Science Journal 43: 107-122.

Mendoza, Ronald U., and Miann Banaag. 2017. “Dynasties Thrive under Decentralization in the Philippines.” Ateneo School of Government (ASOG) Working Paper No. 17-003. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2875583 (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Mendoza, Ronald U., Jan Fredrick Cruz, and David Barua Yap II. 2014. “Political Party Switching: It’s More Fun in the Philippines.” Asian Institute of Management (AIM) Working Paper No. 14-019. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2492913 (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Mendoza, Ronald U., Leonardo M. Jaminola III, and Jurel K. Yap. 2019b. “From Fat to Obese: Political Dynasties after the 2019 Midterm Elections.” Ateneo School of Government (ASOG) Working Paper No. 19-0013. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3449201 (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Mendoza, Ronald U., Miann Banaag, and Michael Yusingco. 2019a. “Term Limits and Political Dynasties: Unpacking the Links.” Ateneo School of Government (ASOG) Working Paper No. 19-005. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3356437 (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Omnibus Election Code of the Philippines. (December 9, 1985). https://comelec.gov.ph/?r=References/RelatedLaws/OmnibusElectionCode (Accessed May 20, 2024)

Rivera, Temario. 2016. “Philippine democratization: Summing-up key conceptual, institutional, and developmental issues.” In F. Miranda & T. Rivera, Eds. Chasing the wind: Assessing Philippine Democracy (pp. 246–262). Quezon City: Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines (CHRP) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Rodan, Garry. 2018. Participation Without Democracy: Containing conflict in Southeast Asia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Schmitter, Philippe. 2015. “Crisis and transition, but not decline.” Journal of Democracy 26, 1: 32-44.

Schneider, Carsten, and Philippe Schmitter. 2004. “Liberalization, transition and consolidation: Measuring the components of democratization.” Democratization 11, 5: 59-90.

Stoker, Gerry. 2006. “Explaining political disenchantment: Finding pathways to democratic renewal.” The Political Quarterly 77, 2: 184-194.

Stoker, Gerry, and Mark Evans. 2014. “The “democracy-politics paradox”: The dynamics of political alienation.” Democratic Theory 1, 2: 26-36.