![[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability: A Case Study of Nepal (Interim Report)](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250403184243822722199.jpg)

[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability: A Case Study of Nepal (Interim Report)

Working Paper | 2024-12-26

Ujjwal Sundas

Director, Samata Foundation

Ujjwal Sundas, Director of the Samata Foundation, explores the state of vertical accountability in Nepal, focusing on the challenges and gaps in its electoral systеm and governance practices. While Nepal’s mixed electoral systеm promotes inclusivity through proportional representation, Sundas highlights critical barriers to accountability, including weak enforcement of election codes, pervasive corruption, and the instability caused by coalition governments. He advocates for essential reforms, such as bolstering the autonomy and effectiveness of the Election Commission, increasing transparency in candidate nominations by political parties, and enhancing voter education through stronger collaboration between civil society and the media.

1. Introduction

Following the People’s Movement of 2006, the country made significant strides towards a more democratic systеm of governance, with notable shifts occurring within the political landscape. All of the country’s major political parties began to emphasize the importance of “inclusion” as a goal. Nevertheless, the change has not significantly benefited the disadvantaged groups, including women, Dalit, Madheshi, Janajati, Muslims, and others. Overall, the level of participation of marginalized groups in the political process remains relatively low, despite the promises of inclusion in terms of caste and ethnicity made by political parties and subsequent governments.

Nevertheless, the people have finally identified a representative after two decades of absence, during which time they experienced a prolonged period of statelessness. Today, at least, the systеm is in place. The groundwork for a genuine democracy has been established. Nevertheless, it is imperative that the government at the local level be fully utilized to capitalize on the opportunities presented by the recent elections. The gradual approach towards an ideal democracy necessitates the integration of the people at the grassroots level with the state mechanism. There has been a notable discrepancy at the local level. The issues of good governance, gender and social inclusion, corruption, and impunity remain largely unaddressed.

At the present time, women and the most marginalized communities, such as the Dalits, are represented in the government. It is a mandatory requirement that each ward at the local level across the country accommodate a Dalit elected member. This is indicative of the progress that Nepal has made in its democratization process. Notwithstanding the altered context, the culture of representation, partnership, and participation remains significantly underdeveloped.

In order to ensure vertical accountability, it is essential to have in place horizontal accountability mechanisms like elections. These include independent and professional media, civil society, and other accountability mechanisms in between elections. In addition, the establishment of horizontal accountability mechanisms, namely the creation of robust and autonomous agencies, will serve to reinforce vertical accountability mechanisms (Lawoti 2019).

2. Rationale of the Study

In Nepal, following the abolition of the monarchy, the general public has been fully exercising their democratic right to choose their own leaders. Nepal, a federal democratic republic, has held significant elections in 2017 and 2022. In accordance with the Constitution, the country has adopted a mixed model of an electoral systеm. In consideration of the country’s context and a meticulous examination of the relative merits and drawbacks of the mixed systеm, the Nepalese electoral systеm incorporates both the First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) and Proportional Representation (PR) methods of voting. It is regarded as one of the most exemplary models of elections, exhibiting the principle of inclusion. Nevertheless, numerous challenges have arisen within the country, particularly with leaders failing to align their actions with the expectations of the electorate and major political parties engaging in a cycle of unstable coalition governments. The country faces a significant challenge in maintaining a stable government. Over the course of 16 years, Nepal has formed a coalition of parliamentarians on 12 occasions. The elected members have frequently switched between being in government and being out of government. The increasing influence of smaller political parties is contributing to a situation in which the formation of coalitions is becoming a determining factor in the political landscape, leading the country towards a state of prolonged instability.

Individuals assume governmental or parliamentary roles on numerous occasions, exploiting the provisions of the systеm. However, it is a crucial question in the present context to whom they are accountable. Those elected through both FPTP and PR appear to prioritize the interests of their respective parties. The election manifestos that are publicly declared right before the election are rarely fulfilled in practice. Individuals with criminal histories have been elected to government positions. Corruption and bribery have been pervasive within the political landscape. The tenets of the election code of conduct are grossly violated. The selection of an unsuitable leader, based on flawed input, has the potential to result in a lack of accountability to the electorate.

A multitude of actors are involved in the electoral process. However, the results of the election are not satisfactory, resulting in significant corruption during and after the electoral process. As a consequence of the lack of accountability of the entities and bodies associated with the electoral systеm in Nepal, a number of issues have become apparent, as outlined below.

Some political issues that have emerged include the formation of a predatory coalition between the ruling party and business houses, an unstable government, the formation of pre-election alliances among political parties, and a lack of effective institutional control over the electoral process. Similarly, there are some legal issues, including violations of the code of conduct during elections, an increase in corruption over the past 15 years (as reported by Transparency International Nepal in 2022), a lack of transparency regarding the rules, laws, and processes, delays in the formulation of laws and rules that have yet to be devised according to constitutional provisions, and a lack of transparency regarding the rules, laws, and processes.

3. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this research is to explore and analyze the accountability of political and legal entities to the general public, identify deficiencies in the electoral systеm in Nepal, and assess the challenges in fulfilling the aspirations of voters.

The following questions are of particular importance:

4. Literature Review

4.1. Government Structure of Nepal

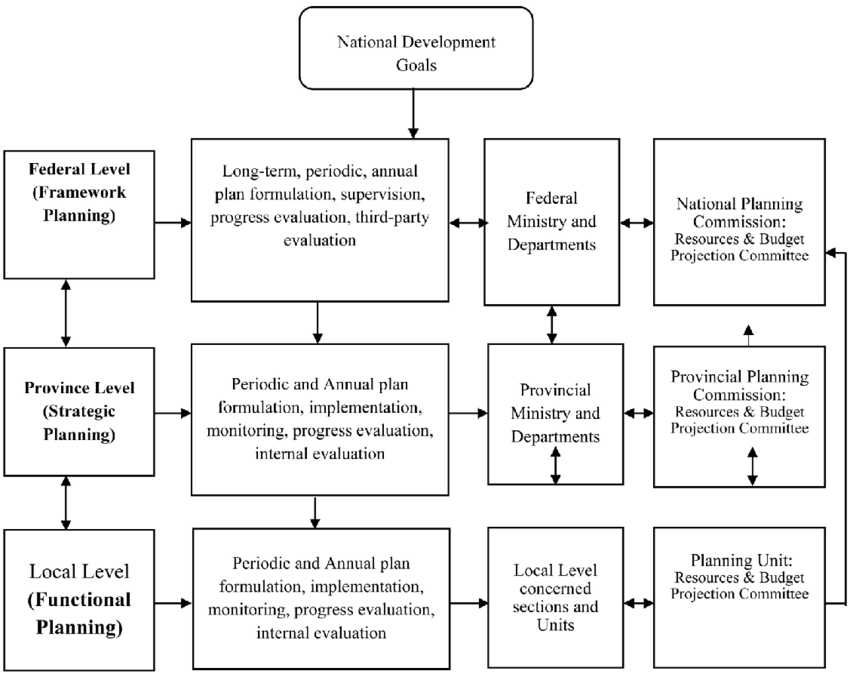

The government of Nepal is structured into three tiers: federal, provincial, and local. In accordance with the constitutional provision, the distribution of state power is allocated among the three-tier government systеm. The governments at the three levels are linked through the establishment of national development goals and objectives, which are set by the National Development Council. An intergovernmental relationship exists among the planning units at each level, both in terms of institutional structure and planning procedure. The distribution of state power among the three-tier government is defined by Article 57 of the Constitution.

The relationship between the three tiers of government is a two-way vertical one. This relationship exists between the federal government (FG), provincial government (PG), and local government (LG) and their respective planning entities during the different phases of the plan. This relationship can be further categorized as either a functional relationship or a resource-wise relationship. A defined relationship exists with regard to policy translation. In the preparation, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation of long-term, periodic, and annual plans, a vertical relationship shall be maintained between the planning entities of the FG, PG, and LG.

Figure 1. Relationship Between Three Tiers of the Government

Source: Taskforce Study Report Formulated by the NPC on 2016/09/25

4.2. Electoral Systеms in Nepal

The electoral systеm in Nepal reflects three key elements: the weight of public opinion, the consideration of popular interest, and the broad-based representation of social, economic, and political concerns of citizens. In addition to these functions, elections serve other vital purposes, including the selection of leaders, the conferral of legitimacy upon governance, and the establishment of accountability between the government and the electorate (Dahal 2001).

Nepal’s electoral systеm differs from the single-member-constituency systеm observed in the USA, UK, and Canada. In these countries, the candidate with the most votes in each constituency is declared the winner, even if this number falls below 50%. Nepal adheres to a mixed electoral systеm.

The Mixed Electoral Systеm (MES) preserves the proportionality benefits of the PR systеm while also ensuring that elected officials are assigned to specific geographical districts. Nevertheless, in instances where voters possess two ballots—one for the political party and one for their local representative—it remains uncertain whether the local representative vote is of lesser consequence than the party vote in determining the overall distribution of seats in the legislative body. Moreover, the MES can result in the creation of two distinct categories of legislators: those who are primarily responsible to and subservient to a constituency, and those who are drawn from the national party list and obedient to the party. Such a situation could have implications for the cohesion of elected political party groups.

The House of Representatives (HoR) is comprised of 275 elected seats, while the State Assemblies (SAs) have a total of 550 seats. The State Assemblies and the House of Representatives will be elected through a mixed electoral systеm, with 60 percent of representatives elected through the FPTP method and 40 percent through a systеm of PR that utilizes closed lists of candidates submitted by political parties. On Election Day, voters are thus required to cast four votes: one for an FPTP candidate for the House of Representatives (HoR), one for an FPTP candidate for their State Assembly (SA), one for the HoR party list, and one for the SA party list (IFES 2021).

5. Accountability of Government Bodies and Other Entities Towards the Voters

5.1. Election Commission

The Election Commission (EC) of Nepal is a constitutional election management body in Nepal. The Constitution of Nepal has established the framework for the EC in Section 24, Articles 245 to 247. The Constitution of Nepal has enshrined the competitive multiparty democratic systеm, adult franchise, and periodic elections as fundamental guiding principles of democracy. In accordance with the constitutional provisions, the Commission bears the responsibility for conducting elections at various levels—federal, provincial, and local bodies—in accordance with the prescribed electoral systеms (Election Commission of Nepal 2017).

The EC is responsible for conducting and supervising the national and local elections, as well as referenda on matters of national importance. They also make a final decision regarding the legitimacy of nominations for candidacy. The EC may delegate its authorities and duties to the Election Commissioner or the Government employee.

It is not feasible to conduct a fair and reliable election with the sole input of the EC. Therefore, in order to ensure the fairness and integrity of the electoral process, various judicial authorities have been established. Some of the aforementioned sectors are as follows:

5.2. Nepal Government

In accordance with Article 57 of the Constitution, the government is tasked with several responsibilities to ensure a clean, fair, and fearless election. These include creating a conducive environment for the election, finalizing election dates in coordination with the EC and political parties, and formulating laws to combat impunity and corruption. The government must also guarantee the safety of voters and candidates, support the Commission in enforcing the code of conduct, and ensure the safe and convenient transportation of senior citizens, individuals with illnesses, and persons with disabilities to voting centers. Additionally, it is responsible for coordinating with the EC to mobilize non-government sectors, as well as engaging election supervisors, media, and social organizations to properly manage and organize the election process.

A government lawyer has specific responsibilities both during and after an election and may be held accountable for fulfilling these duties. They are tasked with aiding and guiding law enforcement agencies in the investigation and prosecution of electoral crimes, ensuring all proceedings are lawful and supported by sufficient evidence. Additionally, they must provide support to plaintiffs in a tactful and effective manner. If a verdict is deemed unsatisfactory, it is the responsibility of the government lawyer to initiate an appeal in a higher court.

5.3. Parliaments

In order to ensure the timely and meaningful conduction of elections, it is incumbent upon parliamentarians to formulate the necessary policies and make the requisite amendments. Similarly, parliamentarians are expected to assess the performance of the EC and the government and provide constructive feedback, recommendations, and guidance as needed.

5.4. Political Parties

It is incumbent upon political parties to instruct their respective cadres to refrain from any form of intimidation, harassment, or unlawful influence exerted upon voters and candidates. Political parties should establish criteria for candidate nomination in accordance with existing legislation.

In collaboration with the EC, civil society organizations, and the government, political parties should implement training programs for their respective cadres to enhance their capacity for conducting fair elections. It is incumbent upon political parties to lend their support to the government in its efforts to control and punish those engaged in election-related crimes.

5.5. Election Supervisor, Civil Society and Media

Election supervisors, members of civil society, and media personnel carry significant responsibilities in ensuring transparency, fairness, and the timely dissemination of election results. The press should exert pressure on the relevant authorities to uphold the highest standards in these areas and assist government bodies in creating a safer environment that protects human rights for all. Collaborating with the EC and government entities, civil society is responsible for implementing voter education programs and ensuring that political parties and candidates adhere to the established election code of conduct. Additionally, they must provide necessary resources, training, and services to support the electoral process effectively.

6. Findings and Analysis

6.1. Uniqueness of Electoral Systеm

The two major elections held after the promulgation of the Constitution in 2015 are distinctive in that they are a mixed systеm (FPTP and PR with a 60:40 ratio). The principle of inclusion is reflected in the PR systеm at both the federal and local levels. The aforementioned reservations are intrinsic to the electoral systеm itself. The scope of the reservation is extensive, encompassing a diverse array of groups, including women, Dalits, Madhesi, Janajati, Muslims, and others. In the presidential, parliamentary, municipal, and ward levels, it is required that the chair and the deputy be of different genders.

A minimum of 33% female representation is required for nearly all formal parliamentary committees, ministries, and other official bodies.

6.2. Degree of Accountability

Members elected at the local level are more directly accountable to the public, whereas members elected at the provincial and federal levels have dual responsibilities: to their political parties and to the general public. It appears that elected members at the provincial and federal levels are more focused on the agenda of their political party and less focused on the needs of the general public. The parliamentarians are dedicated to their party leaders and are engaged in a competitive pursuit of securing an election ticket for the subsequent round, in the hope of pleasing the party leaders.

The party manifesto may initially appear to be quite attractive and in the public interest. However, maintaining a coalition in a multi-party systеm/government is a significant challenge. Therefore, the party manifesto is subject to dilution as a consequence of the greater influence exerted by the dynamics of the coalition.

7. Efforts to Promote Accountability

A number of donors and international development organizations have been providing support to the electoral systеm and the EC in collaboration with the Nepalese government since the introduction of federalism in Nepal. Immediately following the election, training is provided to elected members. A variety of international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and government bodies collaborate to conduct training sessions for elected officials with the objective of ensuring accountability to the general public.

The majority of parliamentarians and ministers do not engage in the training programs. Such individuals often exhibit a self-assured demeanor, suggesting a belief that they possess comprehensive knowledge on the subject matter. Such individuals tend to believe that their extensive political experience and understanding of the nuances of governance equips them with the requisite knowledge to address the needs of the general public.

The training and assistance provided encompass various initiatives aimed at strengthening electoral and governance processes. These include capacity-building programs for the EC, voter education programs, and legislative drafting. Additional training focuses on skills to mitigate conflict and foster collaboration, ensuring that elected officials and civil servants fulfill their responsibilities and remain accountable to the public. Furthermore, specialized programs are offered to empower women to actively engage with the Constitution (Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Admіnistration 2021; Himalayan News Service 2018-02-05; NDI 2009).

7.1. Code of Conduct

The EC has made an election code of conduct for all voters and the candidates (Nepal Election Commission 2022). The code of conduct is disseminated to the general public and political party members through a series of training programs and via the election supervisors.

Some behaviors are overt and can be monitored and regulated, whereas others are covert and conducted surreptitiously. Adherence to the Code of Conduct is of paramount importance for elected officials, both during and after the electoral process. In the context of elections, a number of irregularities have been observed, including the induction of elected members, the use of bribery, the exertion of threats to influence candidacy and results, and the capture of polling stations. The tenets of electoral law are either disregarded or contravened. Campaigning programs often result in significant expenditures that exceed the limits set by the EC. Some candidates seek undue financial support from wealthy businessmen.

In some remote areas of Nepal, incidents such as intimidation and the consumption of alcohol in polling stations are not uncommon. In regions with challenging geographical features and limited transportation options, individuals with disabilities and the elderly may face difficulties in reaching polling centers, thereby hindering their ability to cast votes. Consequently, the number of votes cast for the selected candidate is reduced. The candidate(s) who are able to provide logistical support (travel, food, and accommodation) for the voters may have an advantage in the electoral process. Additionally, some villagers have been offered the waiver of their loans in exchange for casting their votes in accordance with the instructions provided.

Furthermore, the EC has been found to have some shortcomings. Some respondents indicated that the EC is not functioning in an autonomous manner. The dates of the elections are set by the incumbent government without any consultation or discussion with the EC. The financing of election security measures is not subject to sufficient regulation. The efficacy of voter education is undermined by its hasty admіnistration in the period preceding the election. The incumbent government has been observed to deliberately initiate or approve development projects in the period preceding elections. In rural areas, security and order is not adequately maintained.

7.2. Continuous Political Party Rule and the Division of Power

The two major political parties have been in continuous power since 1990. The Nepali Congress (NC) and the Communist Party of Nepal (CPN) – United Marxist-Leninist (UML) have been in government, holding key ministries for the past 34 years. Even after declaration of Nepal as a republican country, they are still in power along with the Nepal Communist Party (NCP). The reason for this is that they are unable to secure an absolute majority (two-thirds) in the lower house. Such parties anticipate the outcome of elections and seek to form alliances in advance, with the objective of achieving the desired result. This has been the case since 2008.

The government was dissolved on 12 occasions between 2008 and the present. In order to maintain a two-thirds majority coalition government, frequent changes have been made to both the cabinet and the arithmetic equations of political party members. The dissolution of a coalition government at the federal level has repercussions at the lower levels as well.

Table 1. Prime Ministers of Nepal since 2008

|

No. |

Prime Ministers |

From |

Till |

Period in Month |

Political Party |

|

1 |

Girija Prasad Koirala |

28-May-08 |

18-Aug-08 |

3 |

NC |

|

2 |

Pushpa Kamal Dahal |

18-Aug-08 |

25-May-09 |

9 |

NCP-MC |

|

3 |

Madhav Kumar Nepal |

25-May-09 |

6-Feb-11 |

21 |

UML |

|

4 |

Jhala Nath Khanal |

6-Feb-11 |

29-Aug-11 |

6 |

UML |

|

5 |

Baburam Bhattarai |

29-Aug-11 |

14-Mar-13 |

19 |

NCP-MC |

|

6 |

Khil Raj Regmi |

14-Mar-13 |

11-Feb-14 |

11 |

Independent |

|

7 |

Sushil Koirala |

11-Feb-14 |

12-Oct-15 |

20 |

NC |

|

8 |

KP Sharma Oli |

12-Oct-15 |

4-Aug-16 |

23 |

UML |

|

9 |

Pushpa Kamal Dahal |

4-Aug-16 |

7-Jun-17 |

10 |

NCP-MC |

|

10 |

Sher Bahadur Deuba |

7-Jun-17 |

15-Feb-18 |

8 |

NC |

|

11 |

KP Sharma Oli |

15-Feb-18 |

13-Jul-21 |

41 |

UML |

|

12 |

Sher Bahadur Deuba |

13-Jul-21 |

26-Dec-22 |

17 |

NC |

|

13 |

Pushpa Kamal Dahal |

26-Dec-22 |

15-Jul-24 |

18 |

NCP-MC |

|

14 |

KP Sharma Oli |

15-Jul-24 |

|

|

UML |

NC: Nepali Congress, UML: United Marxist and Leninist, NCP-MC: Nepal Communist Party-Maoist Center

7.3. Significant Systеmic Corruption

Following the declaration of Nepal as a “secular, federal, democratic, republic nation” in 2008, a significant instance of systеmic corruption emerged. There has been a flagrant abuse of power. Those in positions of power, including ministers, parliamentarians, mayors, and high-level government bureaucrats, have been implicated in acts of corruption. Some have been incarcerated, while others are currently under investigation, and a few more are awaiting trial.

Table 2. List of Significant Instances of Corruption since 2008

|

No. |

Major Scandals |

Approx. Amount (NPR) |

|

1 |

Gold smuggling |

N/A |

|

2 |

Fake Bhutanese Refugees |

288.17 million |

|

3 |

Lalita land scam |

N/A |

|

4 |

Omni scandal |

N/A |

|

5 |

Tax Embezzlement |

10.02 billion |

|

6 |

Budhigandaki Hydropower |

9 billion |

|

7 |

Printing press |

700 million |

|

8 |

CCTV scandal |

N/A |

7.4. Election Expense and Predatory Relations with Businessmen

EC guidelines limit campaign expenses to NPR 2.5 million (equivalent to USD 18,000) for General Assembly and NPR 1.5 million (equivalent to USD 10,800) for Provincial Assembly. Political leaders are seeking the support of businessmen in order to obtain the necessary funds, and in turn, the politicians are working in favor of the businessmen.

A former minister asserts that a minimum of NPR 50 million (equivalent to USD 360,000) is required to secure an election victory. He further states, “Our average five-year income would be approximately four million, and we believe that we must recover this amount during our tenure.”

7.5. Candidacy Nomination by Political Parties

The nomination of candidates by political parties is a common practice in Nepal, observed across the political spectrum, including among smaller and newer parties. In the case of FPTP candidates, nomination is principally based on the contribution of the proposed member to their respective political parties.

The formal process is as follows. Firstly, the district committees nominate members from each district and send the recommendations to the central committee. Subsequently, the central committee members finalize the list of candidates who compete through FPTP. However, in reality, the party president exercises ultimate decision-making authority in an autocratic manner. In addition, undue influences are exerted by neighboring countries with regard to regional politics.

7.6. Selection of PR Candidates

In principle, 110 members of parliaments are selected from Dalits, Janajatis, women and Madheshi communities by central committees of the respective parties. However, in contrast, influential party members, particularly those with the prerogative of the Party President, have been known to make decisions that result in nepotism and favoritism. For example, individuals from the elite and privileged classes and castes have been observed to occupy seats. For instance, in the case of the spouse of the General Secretary of UML, this individual has been elected as a parliamentarian under the PR systеm. From the Nepali Congress, a spouse of a prominent leader serves in the parliament through the PR systеm. Similarly, from the CPN (Maoist), a daughter and brother respectively hold the positions of mayor and speaker in the upper house.

Senior politicians themselves have opted for the PR systеm over direct elections, as it is a more cost-effective option for them. Rather than engaging in electoral competition, some individuals choose to make a financial contribution to the party in question. This can be described as a form of illicit procurement of seats in the PR systеm. Elected members assert that the financial expenditure incurred during the electoral process (FPTP) could potentially reach up to NPR 50 million per seat.

7.7. Political Manifestation during Election

The concept of accountability is not a mandatory legal requirement. In an interview, a former member of the Constituent Assembly observed that voters are not particularly concerned with election manifestos and are instead guided by political parties. He additionally stated that voters anticipate personal benefits from election candidates. Voters are less concerned with the policies and laws that elected members will enact for the general public and instead focus on the potential benefits they may receive from these elected members, such as employment or business opportunities. Additionally, a senior journalist posited that voters should establish deadlines and inquire of elected officials what actions they have taken to ensure accountability.

7.8. The Advent of Novel Perspectives

“The PR model is financially burdensome, as it necessitates greater representation and resources, which consequently increases expenses for the government,” asserted senior leaders from the NC and UML. The influence of minor political parties has resulted in a disproportionate amount of power, which has led to a lack of decision-making progress. The practice of political representation is being misused by political parties. Those who have held prominent positions of authority on numerous occasions are frequently recommended for PR seats. “Those who are concerned about the potential consequences of losing elections under the FPTP systеm are also seeking PR tickets,” states a professor of political science and former chief of the Central Department of Political Science. There have been calls from within the major political parties (such as the NC and the UML) for the removal of the PR systеm and the adoption of a full FPTP systеm. In contrast, the CPN-UML has expressed support for a full PR systеm and direct election of the state head.

8. Conclusion

The relatively low level of voter education in Nepal requires further endeavor. It would be prudent to consider voter education as a continuous process with adequate and timely period rather than a one-time event. In addition, it is imperative that the EC monitor and regulate the mounting costs associated with electoral processes and assume responsibility for the effective oversight of the security and safety of the general public. It would be prudent for the legislature to enact a law that would prohibit political parties from forming pre-alliances prior to the election. Such a measure would help to prevent the manipulation of election results. Voters bear responsibility for selecting inappropriate leaders. They should be encouraged to exercise their right to vote in a considered manner, and to hold elected leaders to account by questioning them about their election manifesto and the timelines they have set for achieving the goals set out in it. Those in positions of leadership and political parties in general should demonstrate respect for the principles of proportional representation and comply with the constitutional provisions that govern them. ■

References

ACE Project. 2005. “Holding the Government Accountable.” https://aceproject.org/ace-en/topics/es/esa/esa05 (Accessed October 14, 2024)

Bishwakarma, J. B. 2013. Dalit in Nepali Media. Kathmandu: Martin Chautari.

Dahal, Dev Raj. 2001. “Electoral Systеm and Election Management in Nepal.” Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. https://aceproject.org/ero-en/regions/asia/NP/Electoral%20Systеm%20and%20Election%20Management%20in%20Nepal.doc/view (Accessed October 14, 2024)

Himalayan News Service. 2018. “Training organised for civil servants, elected representatives.” February 5. https://thehimalayantimes.com/kathmandu/training-organised-civil-servants-elected-representatives (Accessed October 14, 2024)

International Foundation for Electoral Systеms: IFES. 2017. “Elections in Nepal: 2017 House of Representatives and State Assembly Elections.” November 21. https://www.ifes.org/tools-resources/faqs/elections-nepal-2017-house-representatives-and-state-assembly-elections (Accessed October 14, 2024)

Lawoti, Mahendra. 2019. “Democracy, Accountability, And A New Nepal.” Social Science Baha. October 23. https://soscbaha.org/lecture-series/democracy-accountability-and-a-new-nepal/ (Accessed October 14, 2024)

Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Admіnistration. 2021. “Legislative Law Drafting training for local level conducted by Province 1.” https://plgsp.gov.np/legislative-law-drafting-training-local-level-conducted-province-1 (Accessed October 14, 2024)

National Democratic Institute: NDI. 2009. “Nepal: Training Women to Engage in the Constitution-Drafting Process through the Nepali Women’s Leadership Academy.” March 16. https://www.ndi.org/our-stories/nepal-training-women-engage-constitution-drafting-process-through-nepali-women%E2%80%99s (Accessed October 14, 2024)

Nepal Election Commission. 2022. “The Election Code of Conduct, 2022.” https://election.gov.np/admіn/public/storage/HoR/LAw/Election%20Code%20of%20Conduct%20final%20.pdf (Accessed October 14, 2024)

Ocampo, JA, and N Gomez Arteaga. 2014. “Accountable and effective development cooperation in a post-2015 era.” https://www.un.org/en/ecosoc/newfunct/pdf13/dcf_germany_bkgd_study_3_global_accountability.pdf (Accessed October 14, 2024)

Wilson, Evan Michael. 2016. “Answerability versus Enforceability: A Study of Accountability in the Relationships Between Donors and Recipients of Foreign Aid.” Master’s Thesis, Department of Political Science, University of Oslo. https://www.duo.uio.no/handle/10852/51799 (Accessed October 14, 2024)

■ Ujjwal Sundas is a Director of Program and Research at Samata Foundation.

■ Edited by Hansu Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | hspark@eai.or.kr

Center for Democracy Cooperation

Asia

Democracy

Democracy Cooperation

Asia Democracy Research Network

![[ADRN Working Paper] The Impact of the Millennials and Gen Z on Democracy in Northeast Asia](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/202505231731371005535793(0).jpg)

Working Paper

[ADRN Working Paper] The Impact of the Millennials and Gen Z on Democracy in Northeast Asia

Asia Democracy Research Network | 2024-12-26

![[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅲ)](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250428171032795173098(0).jpg)

Working Paper

[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅲ)

Asia Democracy Research Network | 2024-12-26