![[Korea-Japan Joint Work on the World 2050] ① Taking a Future-Oriented Approach to ROK-Japan Partnership](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250401141026395415734.png)

[Korea-Japan Joint Work on the World 2050] ① Taking a Future-Oriented Approach to ROK-Japan Partnership

Working Paper | 2025-03-10

Yul Sohn

President, EAI; Professor, Yonsei University

Yul Sohn, President of the East Asia Institute (EAI) and Professor at Yonsei University, argues that South Korea and Japan must move beyond historical disputes and establish a future-oriented partnership grounded in shared strategic interests. He identifies key challenges the two countries must navigate by 2050?including geopolitical shifts, economic transformation, AI, climate change, and demographic decline?and underscores the need for institutionalized cooperation in economic security, technology, and global governance. Sohn emphasizes that sustained engagement, particularly among younger generations, is crucial for forging a resilient and forward-looking bilateral relationship. However, he cautions that merely deferring unresolved historical disputes risks deepening intergenerational identity conflicts.

The frequent employment of the term “future-oriented Korea-Japan relations” reflects the fact that bilateral relations have been predominantly characterized by both diplomatic dialogue and conflict regarding historical issues. The two nations have long been at odds on the interpretation of history, particularly in relation to Japan’s colonial rule and wartime actions during the years of modern transition.

The normalization of diplomatic relations between Korea and Japan, achieved sixty years ago, was the result of a compromise on historical disputes. However, subsequent decades have necessitated continued diplomatic efforts to address contentious matters, including the narrative of Japan’s history textbooks, the Japanese Prime Minister’s visits to Yasukuni Shrine, and the unresolved statuses of wartime “comfort women” and forced laborers. Even in 2025, these issues remain a significant source of controversy.

With regard to the comfort women issue, the two governments reached the “Korea-Japan Agreement of December 28, 2015, on the Issue of ‘Comfort Women’ Victims.” However, disputes persist concerning both the content of the agreement and its implementation. Similarly, the South Korean government proposed a “third-party reimbursement” plan in 2023 as a resolution for the victims of forced labor, but the issue remains unresolved due to Japan’s insufficient cooperation in meeting South Korea’s expectations. Furthermore, the designation of Sado Island Gold Mines as a UNESCO World Heritage Site has provoked severe backlash within Korea.

In this context, historical conflicts between the nations go beyond being unresolved conundrums in the diplomatic realm, but has evolved into obstructions instrumental in bilateral relations that wield significant influence in areas beyond history and diplomacy, such as in the economy and national security. For instance, former President Lee Myung-bak’s 2012 visit to Dokdo and his demand for an apology from the Japanese Emperor came with the breakdown of the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) negotiations and the termination of the Korea-Japan currency swap agreement. Tensions escalated in 2013 following then-Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s statement denying Japan’s military aggression in the 1930s and 1940s, along with his visit to the Yasukuni Shrine. In 2014, disputes over a resolution to the comfort women issue, coupled with heightened international public diplomacy efforts, further strained bilateral relations.

While the 2015 agreement on comfort women initially provided an opportunity for rapprochement, relations soured again in 2018 following the dissolution of the “Reconciliation and Healing Foundation” and the South Korean Supreme Court’s rulings on forced labor compensation. These developments triggered a series of retaliatory measures, including the radar lock-on dispute in the East Sea, Japan’s 2019 trade restrictions against South Korea and Seoul’s countermeasures, and South Korea’s announcement of its intention to terminate GSOMIA.

The persistent emotional hostility and mutual distrust surrounding history issues has led both governments to hesitate in engaging in cooperative initiatives, to undervalue each other’s strategic significance, and, at times, to adopt overtly adversarial policies. Although the Yoon Suk Yeol government’s proposal of a “third-party reimbursement” plan in 2023 has facilitated a tangible improvement in bilateral relations, historical disputes remain a substantial impediment to achieving long-term stability.

In this regard, the concept of a “future-oriented relationship” serves as a discourse that seeks to transcend the reality in which Korea-Japan relations remain mired in historical disputes, thereby hindering progress on cooperative agendas. In other words, the term “future-oriented” should be understood as a call to prioritize collaborative functional agendas over historical controversies. It emphasizes that historical disputes should not obstruct bilateral cooperation in key areas such as trade, technology, security, and climate change.

Korea and Japan face a multitude of challenges that necessitate joint responses, including North Korea’s nuclear and missile development, China’s attempts at economic coercion, rising protectionist pressures from the United States, the climate and environmental crisis, maritime transport security, and the stable supply of energy resources. The breadth of these shared concerns underscores the significant convergence of national interests between the two countries.

However, merely addressing these areas of cooperation does not inherently constitute a future-oriented Korea-Japan partnership. It is necessary to reconsider the very notion of “future.” The context of Korea-Japan relations must be considered in an extended temporal and spatial dimension that primarily concerns to the younger and future generations, rather than the current generation, which remains primarily concerned with the past and present. For the younger generation, the future is a tangible reality set to unfold in a few decades, around 2045 or 2050, when they come to dominate leadership roles in society and assume the role of the mainstream generation. When that inflection point comes, what kind of future will these generations encounter, and what vision of Korea-Japan relations will they seek to realize?

This study aims to identify the key challenges that the younger generations of Korea and Japan will encounter in the next two decades, define the critical tasks necessary to address these challenges, and explore strategic directions for effective responses. While many initiatives marking the 60th anniversary of Korea-Japan diplomatic normalization in 2025 focus on finding solutions to current bilateral issues, this study takes a forward-looking approach by envisioning the future of Korea-Japan relations for the next generation and formulating a vision for sustained cooperation.

Future Challenges

First, the security challenges of 2050 will likely involve existential threats to humanity. For South Korea, traditional security concerns have been centered on the division of the Korean Peninsula and North Korea’s nuclear and missile development. For Japan, the primary security focus has been on the perceived threat from China. Consequently, the current generation’s security framework is predominantly shaped by the U.S.-South Korea alliance and the U.S.-Japan alliance. However, as future generations become the mainstream of society, key security challenges will include the worsening climate crisis, great power nuclear rivalry, and the risks of AI misuse and loss of control.

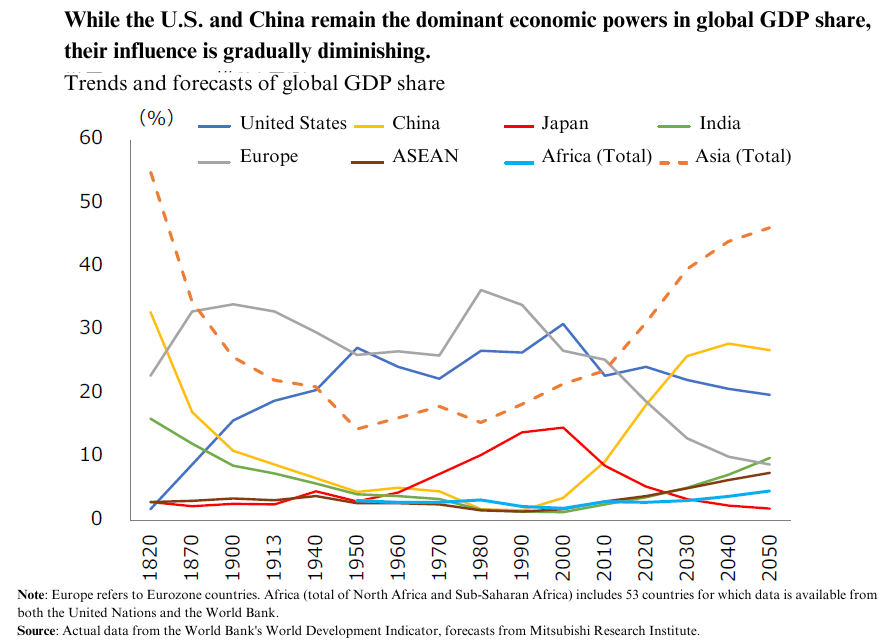

[Figure 1] Trends and Projections of Global GDP Share

A critical factor in shaping the future security order is the evolution of the United States’ global strategy and its regional security strategy in East Asia. As illustrated in [Figure 1], a key determinant of this evolving security landscape is the long-term decline of the U.S. economy. By the 2030s, China’s economy is projected to surpass or closely rival that of the United States. If this occurs, the military power gap—where the U.S. has traditionally maintained a distinct advantage—will inevitably shrink, intensifying strategic competition between the two nations.

As Chun (2025)’s analysis suggests, the U.S. is pursuing strategic adjustments amid a domestic consensus that it can no longer bear the costs of sustaining a unipolar hegemonic systern. The rise and return of President Trump signify a departure from the U.S. commitment to the liberal international order, marking a shift toward a narrower pursuit of national interests and a retreat from its global leadership role. This strategic transformation is closely linked to shifts in the balance of power between the U.S. and China, leading to significant changes in the nuclear order, the governance of advanced technologies, and the alliance structures in East Asia.

Consequently, the future security order that South Korea and Japan will face will undergo a fundamental transformation in response to shifts in U.S. foreign strategy, all while the U.S.-China strategic competition continues to persist and intensify. In adapting to these structural changes, South Korea and Japan must, as Ogi (2025) emphasizes, seek “foundational cooperation” by aligning their policies toward China and North Korea.

The second major challenge is economic transformation. As shown in [Figure 1], the future global economic landscape indicates a marked decline in the economic share of the United States and Europe, while Asia is poised to become the dominant economic center. Over the next 20 to 30 years, ASEAN and India are expected to be the primary drivers of global economic growth. In particular, by 2050, India is projected to emerge as a major economic power alongside the United States and China, forming a tripolar economic structure. In light of these shifts, Korea-Japan economic cooperation must be reoriented from its traditional focus on the United States and Western economies toward deeper integration with Asia.

A more significant systernic change is de-globalization. As Lee (2025) highlights, the United States, which has long upheld a liberal economic order, is shifting toward protectionism, while the rise of economic security concerns has led to increased state control over economic activities. These trends indicate a broader retreat from globalization. While the current strategic challenge for major economies is to devise individual survival strategies (各生, “each seeking its own survival”), the long-term task for future generations will be to revive the benefits of globalization while simultaneously addressing income disparities and mitigating economic security risks, ultimately striving for re-globalization.

Future-oriented Korea-Japan economic cooperation must be structured within a broad framework that remains free and open while also promoting inclusivity and resilience in shaping a new international economic order. As Terada (2025) suggests, South Korea and Japan should establish a high-level “3+3” dialogue, with Japan supporting South Korea’s accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and both countries working to develop a government-private collaboration framework to enhance cooperation in advanced technology sectors.

The third major challenge is the rise of artificial intelligence (AI). As a transformative technology, AI is expected to drive fundamental shifts in military, economic, and political structures. Generative AI, in particular, enables cost reduction, data-driven decision-making, and increased corporate productivity, making it a key driver of national competitiveness. In response, major economies are escalating AI competition, accelerating corporate investments, and widening the global disparity in AI capabilities.

At the same time, AI poses significant risks, including the spread of disinformation, manipulation of public opinion, and heightened societal instability. Concerns are also growing over the potential for AI to be deployed indiscriminately in military applications or to operate beyond human control in various domains, leading to existential threats. Shiono (2025) underscores the critical importance of establishing guidelines that ensure the safe and ethical use of AI technologies.

Baek (2025) identifies the growing decoupling pressures on the global AI ecosystern—driven by U.S.-China AI competition—as a key challenge for South Korea and Japan. As AI middle powers, both countries would benefit from a more integrated AI ecosystern, making policy cooperation essential in addressing this issue. He suggests that the two countries align their mid-to-long-term AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) visions and foster trans-generational, full-cycle cooperation spanning the entire AI development process—from planning and design to implementation. Additionally, he proposes the joint development of AGI-driven projects aimed at achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

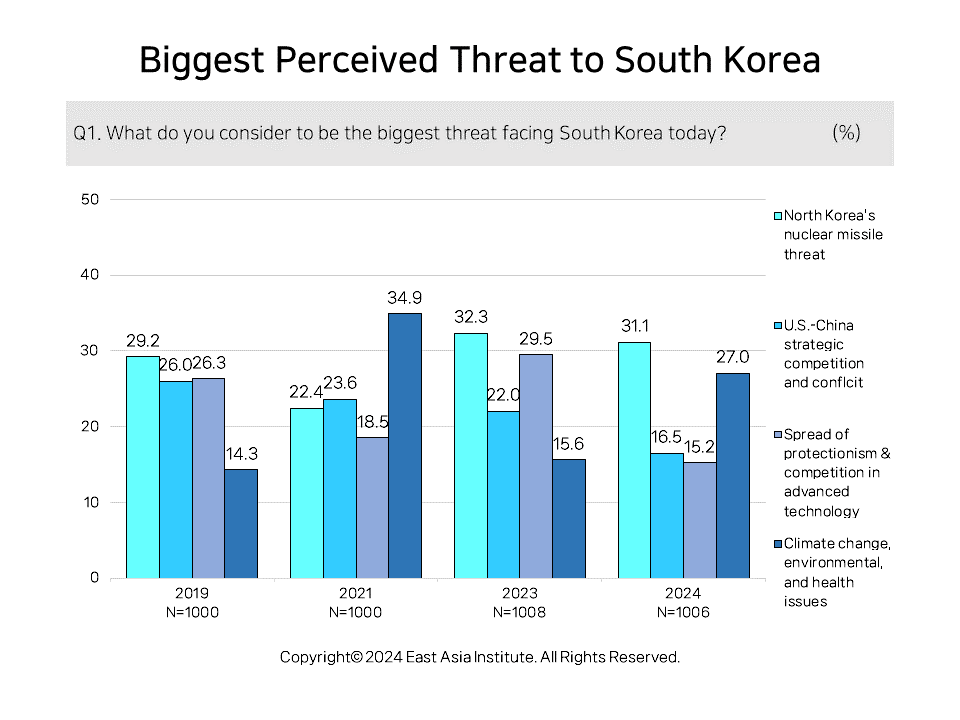

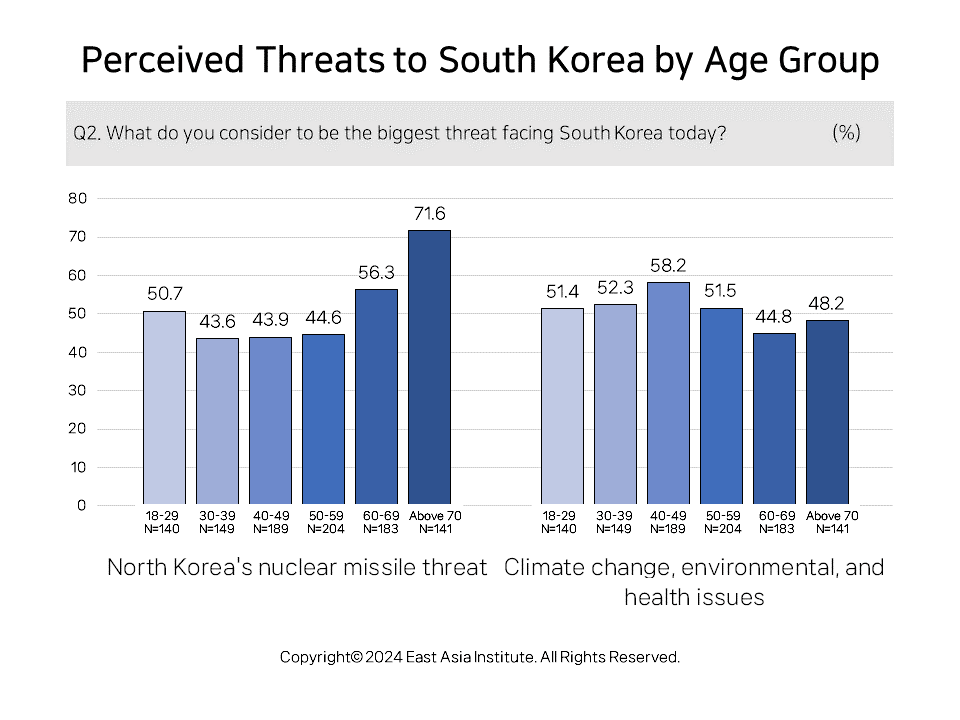

The fourth major challenge is climate change and energy crisis. These issues pose existential threats to humanity, making them among the most formidable challenges that future generations will face. Consequently, compared to the current generation, younger generations inevitably exhibit a heightened sense of urgency. For instance, as shown in the 2024 EAI public opinion survey ([Figure 2, 3]), South Korean youth perceive fine dust pollution as a major threat, reflecting a distinct security perspective from that of the older generation.

[Figure 2] Perceived Threats to South Korea

[Figure 3] Perceived Threats to South Korea by Age Group

Given that both Japan and South Korea remain heavily dependent on fossil fuels for their energy supply, achieving “carbon neutrality by 2050” stands as one of their most pressing future challenges. Over the past six decades, South Korea’s average temperature has risen from 11.03°C in 1965 to 13.32°C in 2023, an increase of 2.29°C. Similarly, Japan has experienced a rise from 10.04°C in 1965 to 12.99°C in 2023, marking an increase of 2.95°C. Consequently, the carbon neutrality targets established under the 2015 Paris Agreement pose an immense challenge for both countries. Given that their rates of temperature increase are projected to exceed the global average, the impact of this transition on their energy and industrial sectors will be profound—akin to a seismic shift in their economic structures.

In this context, Harada (2025) and Lim (2025) emphasize that a comprehensive energy transition and international cooperation are essential. They argue that South Korea and Japan must actively pursue joint initiatives, including LNG co-development and market integration, advancements in decarbonization technologies, and enhanced collaboration in renewable energy and nuclear power.

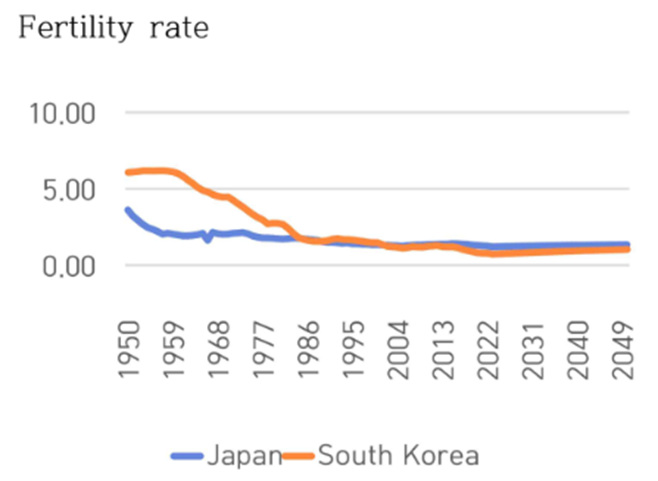

The fifth major challenge is demographic change. This issue is particularly pronounced in South Korea and Japan, stemming from unique domestic factors. Currently, both countries rank among those with the highest life expectancy in the world. In 2022, South Korea’s life expectancy was 83.5 years, while Japan’s was 84.7 years, significantly exceeding the OECD average of 80.5 years. A longer life expectancy increases the proportion of elderly individuals, contributing to the overall aging of the population. However, both countries also have the lowest fertility rates globally, further accelerating population aging. As shown in [Figure 4], the sharp decline in birth rates has led to a decreasing proportion of young people, while the elderly population is expanding at a rapid pace.

[Figure 4] Drops in Fertility Rate, 1950-2049

As 2050 approaches, both countries will face a demographic crisis with far-reaching consequences. Several critical challenges are anticipated. First, a declining population, particularly within the working-age demographic, will lead to severe labor shortages. Second, a fiscal crisis is likely to emerge due to the escalating costs of social welfare, driven by an aging population. Rising healthcare expenses and increasing pressure on the pension systern will further exacerbate financial instability. Third, the risk of local depopulation will intensify as younger generations increasingly concentrate in metropolitan areas. As urban migration accelerates, fertility rates in rural regions are expected to decline even further, placing these areas at risk of long-term socioeconomic decline and potential extinction. As Sagara and Han highlight, addressing these challenges is imperative for future generations; however, the current generation continues to defer difficult but necessary policy solutions.

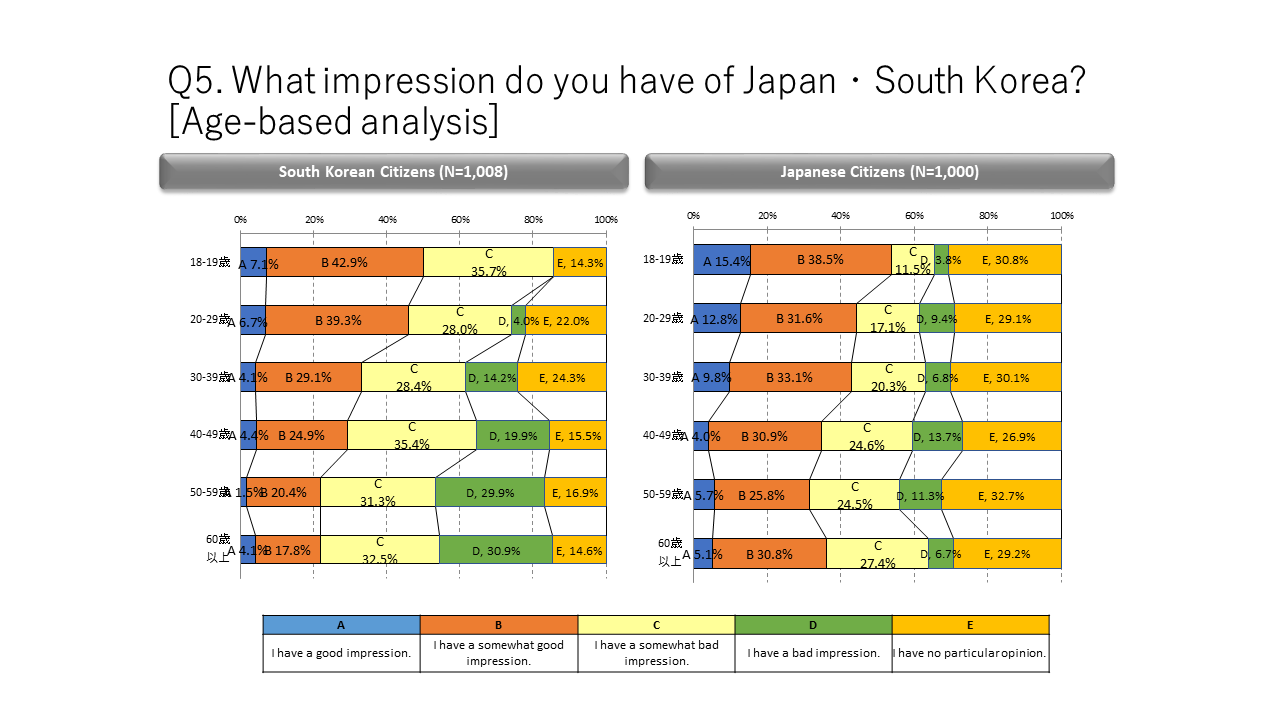

Lastly, the future generations of Japan and South Korea share a common identity as advanced nations, characterized by their commitment to universal values as democratic states, their possession of cutting-edge technologies, and their high standard of living as leading global economies. According to the EAI public opinion survey ([Figure 5]), younger generations in both countries exhibit significantly higher levels of mutual affinity compared to older generations, particularly the elderly. Unlike the identity-based divisions prevalent among older generations—who often frame relations through the historical dichotomy of “empire vs. colony”—younger generations are less influenced by notions of superiority or inferiority. Instead, as indicated by Park (2025), they tend to evaluate each other through the lens of universal values and shared principles as advanced nations.

[Figure 5] Perceptions of the Other Country by Age Group

For instance, in response to the 2019 trade dispute triggered by Abe’s export restrictions on semiconductor materials, the South Korean government at the time framed the issue as “economic aggression” by Japan. However, younger generations criticized the Abe administration based on principles of “fairness” and “justice,” rather than perceiving it solely through the historical framework of colonial oppression. Similarly, historical issues are increasingly being assessed not just in terms of colonial rule and subjugation, but from a broader human rights perspective.

Furthermore, the primary consumers of Korean and Japanese popular culture are the younger generations. Increased engagement with each other’s cultural products—such as popular music (K-pop/J-pop), cuisine, films and dramas, manga/anime, and literature—correlates with a more positive national image and higher levels of mutual affinity. This cultural exchange reflects a growing convergence in cultural identity among younger generations in both countries.

If the values and identities of future generations are to develop independently, they must not be constrained by the fixed paradigms of the older generation, such as the “anti-Japan” vs. “anti-Korea” divide. However, if the current generation neglects efforts to resolve historical disputes and outstanding issues and instead defers them to future generations, it risks perpetuating intergenerational identity conflicts.

As South Korea and Japan commemorate the 60th anniversary of diplomatic normalization, concerns and uncertainties driven by leadership risks have, in many ways, overshadowed optimism for the future of bilateral relations. This makes it all the more imperative to adopt a long-term, strategic perspective and collaborate in jointly shaping a shared future. Crucially, this vision must be informed by and reflective of the experiences and aspirations of future generations. ■

References

Baek, Seoin. 2025. “Korea-Japan AGI for Science, Science for AGI Cooperation.” In Korea-Japan Joint Work on World 2050. EAI-KF-API Working Paper Series.

Chun, Chaesung. 2025. “Future Military and Security Environments Toward 2050: Challenges and Opportunities for Korea-Japan Relations.” In Korea-Japan Joint Work on World 2050. EAI-KF-API Working Paper Series.

Han, Joon. 2025. “How can South Korea and Japan Overcome the Impending Population Risk Together?” In Korea-Japan Joint Work on World 2050. EAI-KF-API Working Paper Series.

Harada, Daisuke. 2025. “Prospectives of Cooperation between Japan and Korea toward Carbon Neutrality 2050.” In Korea-Japan Joint Work on World 2050. EAI-KF-API Working Paper Series.

Lee, Junghwan. 2025. “The Long-Term Vision for ROK-Japan Economic Cooperation in the Era of Deglobalization and Shrinking.” In Korea-Japan Joint Work on World 2050. EAI-KF-API Working Paper Series.

Lim, Eunjung. 2025. “2050 South Korea-Japan Cooperation in Energy and Climate Change-Related Areas.” In Korea-Japan Joint Work on World 2050. EAI-KF-API Working Paper Series.

Ogi, Hirohito. 2025. “Adjusting Net Imbalances of Benefits in Complex Geopolitics: Foundational Security Cooperation between Japan and South Korea.” In Korea-Japan Joint Work on World 2050. EAI-KF-API Working Paper Series.

Park, Jisoo. 2025. “Youth as Catalysts: Building a Renewed Momentum for ROK-Japan Relations.” In Korea-Japan Joint Work on World 2050. EAI-KF-API Working Paper Series.

Sagara, Yoshiyuki. 2025. “Declining Population, Increasing Human-Machine Teaming.” In Korea-Japan Joint Work on World 2050. EAI-KF-API Working Paper Series.

Shiono, Makoto. 2025. “Safety and Ethics Guidelines for AI Cooperation between South Korea and Japan.” In Korea-Japan Joint Work on World 2050. EAI-KF-API Working Paper Series.

■ Yul Sohn is President of East Asia Institute (EAI) and Professor at Yonsei University.

■ Edited by Chaerin Kim, Research Assistant

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | crkim@eai.or.kr

Center for Japan Studies

Korea-Japan Future Dialogue

![[ADRN Working Paper] The Impact of the Millennials and Gen Z on Democracy in Northeast Asia](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/202505231731371005535793(0).jpg)

Working Paper

[ADRN Working Paper] The Impact of the Millennials and Gen Z on Democracy in Northeast Asia

Asia Democracy Research Network | 2025-03-10

![[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅲ)](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250428171032795173098(0).jpg)

Working Paper

[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅲ)

Asia Democracy Research Network | 2025-03-10