Introduction

In a historic decision, the Indian Parliament in a special session recently passed the long-awaited Women Reservation Bill (officially called the Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam, 2023). The legislation (106th Constitutional Amendment Act), which received the president’s approval on September 28, establishes a requirement to reserve one-third of the total seats in the Lok Sabha (Lower House of the Parliament), Vidhan Sabha (state legislative assemblies), and the Legislative Assembly of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (Pathak and Roy 2023). The law will become effective following the completion of the Census in 2026 and the delineation of constituencies, which will be used as the basis for allocating seats to women (Government of India 2023). As per the new legislation, this reservation will remain in effect for a period of 15 years and can be extended by the Parliament. Furthermore, the allocation of seats set aside for women will undergo rotation after each delineation. The new law, when implemented, will increase women Members of Parliament (Lok Sabha) to 181 seats (from the current 82) and Members of Legislative Assemblies (Vidhan Sabha) to as much as 2000 (currently 740).

The passage of the historic women reservation bill is an outcome of 27 years of relentless struggle by women activists and its strong votaries. While the issue of women’s reservation was flagged up in the 1980s, the first serious attempt to get legislation was made in 1996 by the then Congress government. Though unsuccessfully, further attempts were made by a number of governments at the center in 1998, 1999, and in 2008. The most serious attempt to bring legislation was made in 2010 by the then Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. A bill seeking women’s reservation in the Lok Sabha and state legislatures was passed in the Rajya Sabha (Upper House) in 2010, but it failed to get the approval of the Lok Sabha due to strong opposition from the politicians of heartland states (Rajvanshi 2023). Finally, the bill was successfully steered by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government with near consensus from opposition parties. Of course, it has taken a few decades of consensus building and political awareness and sensitization on gender equality to get this important legislation passed in a large country with strong patriarchal norms and rigid social mores (Manoj C G 2023).

A Long Struggle for Gender Equality

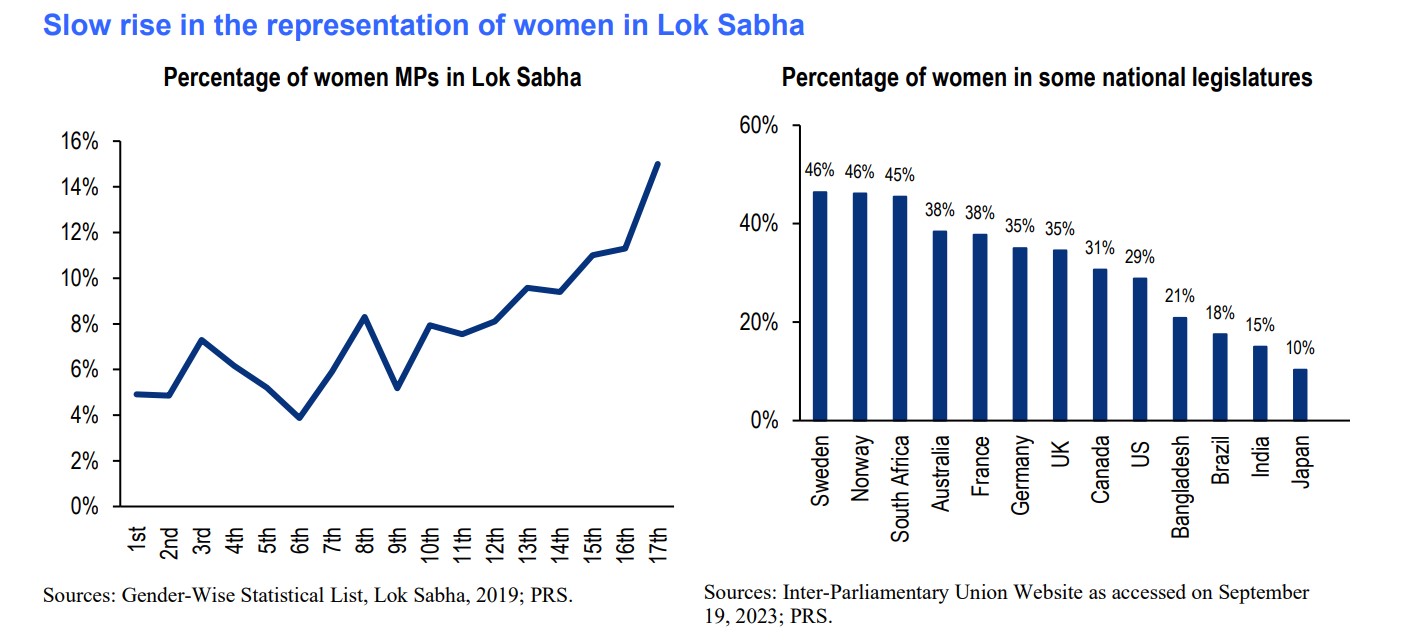

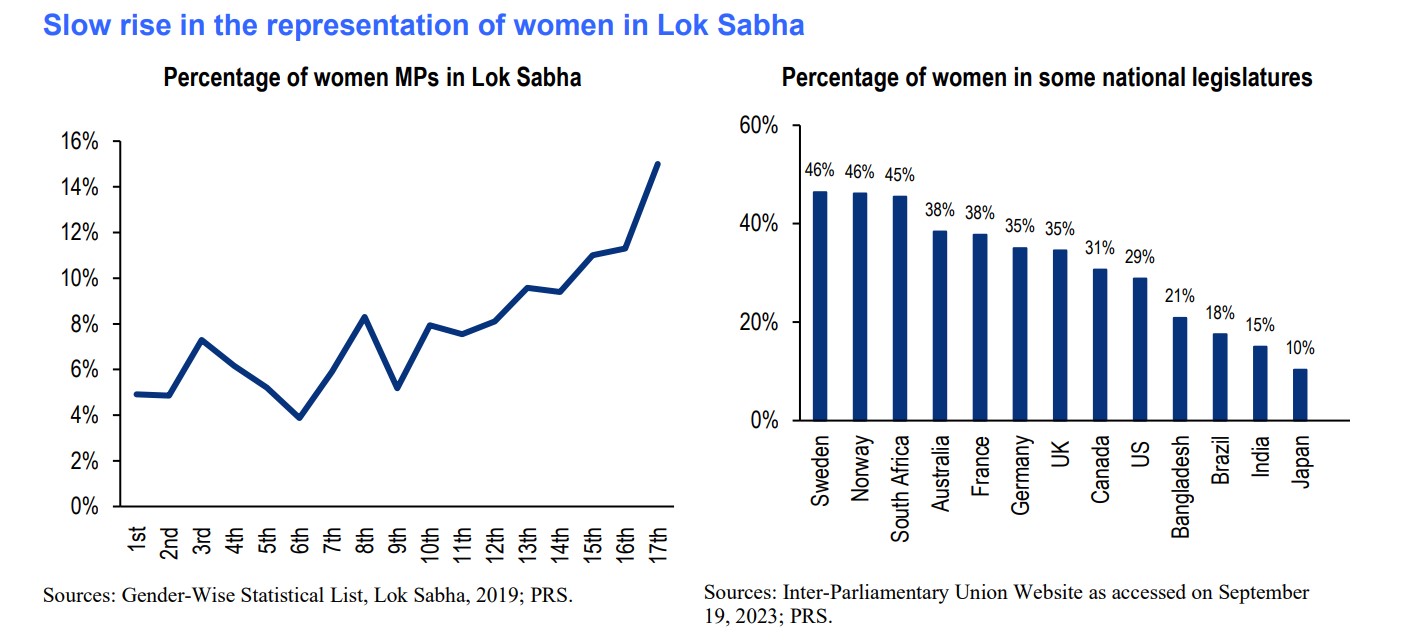

The compelling reason for having more women in parliament and assemblies stemmed from the very low presence of women in politics. For instance, the latest Global Gender Gap Report ranks India 141 out of 185 countries (World Economic Forum 2023). This is clearly evident from the low presence of women in the upper echelons of politics. As per the latest data, women occupy only 15.2 percent of seats in the Lok Sabha and 13.9 percent in the Rajya Sabha (Fleck 2023). In state legislative assemblies or Vidhan Sabhas, the average representation of women is even lower, standing at less than 10 percent (Bhatt 2021; Ramakrishnan et al. 2021). In some states like Nagaland, women representation in assemblies is as low as 3.1 percent. A meager 14 percent representation of women in the national parliament reflects deep-seated structural gender inequality. A major barrier is that very few women get the opportunity to fight elections. For instance, both the national parties, the Congress and the BJP, fielded as low as 54 and 53 women candidates in the 2019 general elections (India Today 2019).

In terms of global and regional comparisons, India’s gender representation looks seriously abysmal. Based on data from IPU Parline, a global resource tracking national parliamentary statistic, as of May 2022, the average proportion of women in these parliaments worldwide stood at 26.2 percent (14 percent for India). Although the Americas, Europe, and Sub-Saharan Africa surpassed this global average in terms of women’s representation, regions like Asia, the Pacific, and the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) fell short on women representation (Ghosh 2022).

However, it is worth noting that even in the laggard Asia and South Asia in particular, India fares worse as far as gender representation in politics is concerned. As per the latest IPU data, in South Asia, Nepal had 33.6 percent female representation, while Bangladesh had 20.9 percent, Pakistan had 20.5 percent, Bhutan had 17.4 percent. Only Sri Lanka had 5.3 percent (IPU 2022). Afghanistan was not included in this study, but data from the World Bank in 2021 indicated that the last parliament in Afghanistan before Taliban takeover had a female representation of 27 percent. Although a number of women have risen to occupy the posts of Chief Ministers (heading state governments) including in some of the politically charged states as Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Rajasthan, they continue to face multiple barriers particularly patriarchal norms, sexism, institutional discrimination, violence, lack of support from facilities among others to compete for political offices (Brechenmacher 2023).

Table 1. Global Average of Women’s Representation in Parliament

|

|

Lower chamber and unicameral

|

Upper chamber

|

All chambers

|

|

Total No. of MPs

|

37,248

|

7,062

|

44,310

|

|

Men

|

27,425

|

5,255

|

32,680

|

|

Women

|

9,823

|

1,807

|

11,630

|

|

Percentage of women

|

26.4%

|

25.6%

|

26.2%

|

Source: IPU Parline: Global Data on National Parliament (as of May 2022)

Figure 1. Women Representation in Lok Sabha

Source: PRS Legislative Research 2023

Table 2. Women’s Representation in Parliament, by Geographical Region

|

Region

|

Parliamentary representation of women (in percentage)

|

Region

|

Parliamentary representation of women (in percentage)

|

|

Americas

|

34.6

|

Europe

|

31.1

|

|

Caribbean

|

39.7

|

Nordic Countries

|

44.7

|

|

North America

|

38.2

|

Western Europe

|

35.2

|

|

South America

|

30.1

|

Southern Europe

|

31.1

|

|

Central America

|

29.5

|

Central and Eastern Europe

|

24.3

|

|

Sub-Saharan Africa

|

26.0

|

Asia

|

20.9

|

|

East Africa

|

32.0

|

Central Asia

|

26.1

|

|

Southern Africa

|

31.8

|

Southeast Asia

|

21.8

|

|

Central Africa

|

22.5

|

East Asia

|

21.8

|

|

West Africa

|

16.9

|

South Asia

|

16.7

|

|

Middle East and North Africa

|

16.8

|

Pacific

|

20.9

|

|

Middle East

|

17.1

|

Australia and New Zealand

|

42.2

|

|

North Africa

|

16.4

|

Pacific Islands

|

6.0

|

Source: IPU Parline: Global Data on National Parliament (as of May 2022)

Impressive Success Stories at the Local Governments

However, India has done quite well in fostering gender equality at the local level. In the 1990s, India ushered a path-breaking decentralized systеm of governance at the local levels (both rural and urban spheres) (Shanker 2014). The passage of historic 73rd and 74th constitutional amendments which aimed at creating opportunities for local-level planning, more effective implementation, and better monitoring of various social and economic development programs across the country included the most transformative provision of reserving one-third of the total seats in local bodies for women (Joshi 2018; Chawla 2021). Recent studies have demonstrated that this law has led to a remarkable increase in the political engagement of women at the grassroots level (Sahoo and Chavaly 2022). Consequently, 20 out of India’s 28 states have subsequently elevated women’s quota to 50 percent of the elected offices of rural local bodies. As a consequence of this, a mammoth 1.45 million elected women representatives have come up at various levels of local governments.

The significant point is that the gender quota at the grassroots level has bolstered the political empowerment of women. A recent report indicates that approximately 44 percent of local government positions in India are now held by women (Joshi 2022). This remarkable achievement places India at the forefront of nations worldwide that are promoting women’s political empowerment at the local level. India surpasses other major countries like France, the UK, Germany, and Japan in this regard and even exceeds the global average of 34.3 percent. Although concerns have been raised in the past about women in reserved seats being potentially manipulated by male politicians, recent studies demonstrate that exposure to public life and participation in leadership skills training programs have facilitated the emergence of numerous competent and capable women leaders in India’s local political landscape (PRIA 1999). The consistent growth of women’s representation in local politics and the development of political agency among women leaders, thanks to the reservation of seats in local government, offer a blueprint for enhancing women’s political engagement in national and state politics. This becomes especially relevant when the Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam law is put into practice.

Some Concerns but Hopeful Prospect

While the passage of the women reservation bill is long overdue and likely to open up crucial democratic space for women at the top levels, the path to greater gender equality is still going to be a long struggle. To begin with, there are numerous roadblocks to the new legislation. First, the women’s quota legislation is not going to be implemented with immediate effect. Its implementation is predicated upon the completion and publication of the new Census and the delimitation exercise which is slated to begin in 2026. The real risk to the new legislation is serious uncertainty over the fate of delimitation. It may be recalled that delimitation, which is a major bone of contention between the southern and northern states, has been frozen since 1976. Given the exercise likely to open up fault lines in India’s fragile federal systеm, it is uncertain whether the government will take a call on this. Thus, the delimitation sword hangs on the fate of the reservation bill.

Second, there is speculation about the nature and contours of the new law and its subsequent rollout. Given the new legislation has not specified the issues of representation of women from the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) that constitutes a sizeable section of the population, there are apprehensions that women from such backward groups might remain deprived from the benefit of the quota law (Dahiya 2023). Also, a number of political parties particularly from Hindi heartland states have also demanded a sub-quota for women from the backward classes and religious minorities (Sinha 2023). Caution needs to be exercised in order to ensure that the quota law does not only benefit political dynasties and urban and economically better-off women. (Agnes 2023).

Third, some analysts fear that women candidates are likely to be nominated by male family members or patrons who ultimately will influence or control their decisions. Thus, there are chances of proxies that would call the shots in parliament and assemblies.

Fourth, the bill does not address the inadequate women representation in the Rajya Sabha as well as State Legislative Councils (upper house of state-level legislatures) which also has elected an extremely low proportion of women as members so far.

Finally, there are strong apprehensions that the new systеm with the rotation of seats every five years is likely to create uncertainty and instability in the electoral process (Agnes 2023). The change of constituencies every five years would negatively impact the continuity and accountability of elected representatives to their constituents.

Notwithstanding these infirmities and some uncertainty over its actual rollout, the new law holds plenty of promise on gender equality and governance which is responsible to women in India. Given many positive outcomes that have emerged due to gender quota at the local levels, many analysts see increased women presence in parliament and state assemblies can make the policy space more sensitive to the needs and aspirations of women. Plus, as seen from the global experience and from India’s own experiment at the local level, having more women in crucial decision-making bodies can lead to increased spending on health, education, sanitation, and developmental schemes that benefit women and children. In short, the new legislation can be a game changer for gender equality in a large country marked by rigid patriarchal norms and social conditions. ■

References

Agnes, Flavia. 2023. “Real commitment to women’s representation will be seen in 2024 Lok Sabha polls.” The Indian Express. September 25. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/womens-reservation-bill-the-inclusion-test-8954328/

Bhatt, Pankhuri. 2021. “Women’s Representation in India’s State Legislative Assemblies.” Samvidhi. July 11. https://www.samvidhi.org/post/women-s-representation-in-india-s-state-legislative-assemblies

Brechenmacher, Saskia. 2023. “India’s New Gender Quota Law Is a Win for Women – Mostly.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. September 26.

Chawla, Akshi. 2021. “A revolution in local politics.” IDR Online. January 22. https://idronline.org/a-revolution-in-local-politics-women-participation/

Dahiya, Himanshi. 2023. “‘Quota within quota’: Understanding Caste Dynamics of Women’s Reservation Bill.” The Quint. September 19. https://www.thequint.com/news/politics/womens-reservation-bill-caste-politics-bjp-congress-bsp-rjd

Fleck, Anna. 2023. “India’s Path Towards Greater Gender Equity in Parliament.” Statista. September 26. https://www.statista.com/chart/30910/share-of-women-in-indias-lower-house-and-upper-house/

Ghosh, Ambar Kumar. 2022. “Women’s Representation in India’s Parliament: Measuring Progress, Analysing Obstacles.” ORF Occasional Paper No. 382.

Government of India. 2023. “The Constitution (One Hundred and Sixth Amendment) Act, 2023.” September 28. https://egazette.gov.in/WriteReadData/2023/249053.pdf

India Today. 2023. “724 women, 4 transgender candidates in fray for 2019 Lok Sabha polls.” May 23. https://www.indiatoday.in/elections/lok-sabha-2019/story/724-women-4-transgender-candidates-in-fray-2019-lok-sabha-1532288-2019-05-22

Inter-Parliamentary Union: IPU. 2022. “Parline – global data on national parliaments.” https://data.ipu.org/women-averages?month=5&year=2022&op=Show+averages&form_build_id=form-8t9vx839F4GPWWbSuGDMqsgQed3R3GlWQbSgtwIS96M&form_id=ipu__women_averages_filter_form

Joshi, Madhu. 2018. “Promoting women in grassroots governance: Strategies that work.” IDR Online. September 26. https://idronline.org/promoting-women-in-grassroots-governance-strategies-that-work/

Joshi, Ritika. 2022. “Data Reveals 44 Percent Of Seats In Local Government In India Are Held By Women.” Shethepeople. August 27. https://www.shethepeople.tv/news/un-women-in-local-government-seats/

Manoj C G. 2023. “Hanging fire for 27 years: How Women Reservation Bill kept lapsing through its tumultuous journey.” The Indian Express. September 19. https://indianexpress.com/article/political-pulse/hanging-fire-for-27-years-how-women-reservation-bill-kept-lapsing-through-its-tumultuous-journey-8945864/

Pathak, Vikas, and Esha Roy. 2023. “Women’s reservation Bill gets Parliament seal.” The Indian Express. September 22. https://indianexpress.com/article/india/womens-bill-gets-parliament-seal-33-per-cent-quota-for-women-in-lok-sabha-state-assemblies-set-to-become-law-8950720/

Participatory Research in Asia: PRIA. 1999. “Women’s Leadership in Panchayati Raj Institutions: An analysis of six states.” https://pria.org/knowledge_resource/1533206139_Women’s%20Leadership%20in%20Panchayati%20Raj%20Institutions.pdf

Rajvanshi, Astha. 2023. “Why India’s Women’s Reservation Bill Is a Major Step Forward.” Time. September 22. https://time.com/6316383/india-womens-reservation-bill/

Ramakrishnan, Anoop, N R Akhi, Manish Kanadje, and Mridhula Raghavan. 2021. “Explained: Share of women, youth in new state Assemblies.” The Indian Express. May 5. https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/assembly-elections-benal-tamil-nadu-kerala-share-of-women-youth-in-new-assemblies-7300884/

Sahoo, Niranjan, and Keerthana Chavaly. 2022. “Decentralisation @75: How the third-tier institutions have deepened India’s Democracy?” ORF Expert Speak. August 15. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/decentralisation-75-how-the-third-tier-institutions-have-deepened-indias-democracy/

Shanker, Richa. 2014. “Measurement of Women’s Political Participation at the Local Level: India Experience.” https://unstats.un.org/unsd/gender/mexico_nov2014/Session%206%20India%20paper.pdf

Sinha, Shishir. 2023. “Political parties urge passage of women’s reservation Bill in Parliament’s special session.” The Hindu businessline. September 17. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/political-parties-urge-passage-of-womens-reservation-bill-in-parliaments-special-session/article67319025.ece

World Economic Forum. 2023. Global Gender Gap Report 2023. https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-gender-gap-report-2023/

■ Niranjan Sahoo, Ph.D., is a Senior Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

■ Ambar Kumar Ghosh is an Associate Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

■ Typeset by Hansu Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | hspark@eai.or.kr

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] India’s Women Quota Law is a Game Changer for Gender Inclusive Politics](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20231117225842800771094.jpg)

![[EAI Issue Briefing] Expectations and Challenges for Improved Relations with “Unfavorable” China under the Lee Administration: 2025 EAI Public Opinion Poll on East Asia](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2025070114329345217651(0).jpg)

![[EAI Issue Briefing] The Public Prioritizes a Future-oriented Cooperation over Resolving the History Problem in Korea-Japan Relations: 2025 EAI Public Opinion Poll on East Asia](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20250627164526777359170(0).jpg)