![[Working Paper] Convenient Compliance: China’s Industrial Policy Staying One Step Ahead of WTO Enforcement](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/201505131161734.jpg)

[Working Paper] Convenient Compliance: China’s Industrial Policy Staying One Step Ahead of WTO Enforcement

Future of Trade, Technology, Energy Order | Working Paper | 2015-05-13

Seung-Youn Oh

Fellows Program on Peace, Governance, and Development in East Asia

Author

Seung-Youn Oh is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at Bryn Mawr College starting Fall 2013. She specializes in international relations and comparative politics in East Asia. Her broader academic interests include China’s industrial restructuring and upgrading, state-owned enterprise reform and corporate governance, the effects of national origin of foreign direct investment on local economic development, as well as the evolving role of Chinese governments at the national and sub-national levels in shaping the country’s developmental path.

Seung-Youn is currently working on her book manuscript based on her dissertation, The Limits of Liberalization: Sub-National Government Autonomy and the Auto Industry in Post-WTO Era China. In the dissertation, she seeks to understand effects of international linkages on regional economic development in China, with a specific focus on China’s burgeoning automotive industry.

Her recent articles have appeared in China Quarterly and Asian Survey. Prior to coming to Bryn Mawr, she served as a post-doctoral fellow at the Center for the Study of Contemporary China at the University of Pennsylvania for the year 2012-2013. She has also served as a visiting lecturer at the Shanghai branch of the French school of management, École Supérieure des Sciences Commerciales from 2009 to 2012.

In addition, Seung-Youn served as the Northeast Asia Project Director at the Berkeley Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Study Center, where she assisted in organizing the conference for the volume, Asia’s New Institutional Architecture: Evolving Structures for Managing Trade, Financial and Security Relations (Vinod K. Aggarwal and Min Gyo Koo, eds., Springer Verlag, 2008). She has been a research fellow of the Korean Foundation for Advanced Studies (KFAS) and a visiting scholar at the Institute of World Economics and Politics of the Chinese Academy of Social Science (CASS) in Beijing, China. Seung-Youn holds an M.A. and Ph.D in Political Science from the University of California at Berkeley and a B.A. in Political Science as valedictorian from Yonsei University in Korea. She spent a year as an undergraduate exchange student at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Abstract

Through case studies of China’s WTO trade disputes in the automobile and wind turbine sectors, I argue that China’s compliance with WTO rulings reflects Beijing’s skillful navigation through the WTO’s dispute-resolution process rather than socialization to international norms. China liberally implements industrial policies and removes them after they come into dispute at the WTO — strategies that I characterize as “convenient compliance.” By the time China removes the challenged measures, it often no longer needs them, since it has already achieved its goals and can still build up a reputation as a responsible WTO member by complying with the organization’s rulings. The dynamics of the global supply chain certainly complicate foreign business groups’ interests and countries’ domestic political calculations regarding trade disputes with China.

China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 was hailed as a significant step forward in opening up China’s markets and curbing governmental practices that placed foreign firms at a competitive disadvantage. While moving from being a cautious observer to an active participant in the WTO, China has demonstrated an outstanding record of compliance with the organization’s dispute settlement rulings; in most cases, Beijing has either reached agreement with the complainant over the disputed practices or removed measures the WTO finds inconsistent with China’s WTO obligations. As such, China’s record at the WTO appears to confirm international relations and legal studies scholarship on international organizations’ effectiveness in socializing and pressuring China for further economic liberalization.

However, China’s achievement in this regard is overshadowed by foreign governments’ and businesses’ increasing criticisms regarding their diminishing access to the Chinese market and Beijing’s continuing use of WTO-inconsistent industrial policy measures. In recent years, trade disputes involving China at the WTO have increased, focusing on the issues of subsidies, anti-dumping, favorable treatment of domestic companies, and discrimination against foreign businesses or imports. This begs the question of how to reconcile two different pictures: China’s continuing reliance on industrial policy measures that contradict WTO rules and its record of successful compliance within the WTO’s dispute-settlement process. Conventional wisdom views China’s compliance with the WTO rulings as a measure of China’s socialization to international norms and the effectiveness of WTO’s dispute-settlement process in addressing trade concerns with China, as compared to the era of bilateral negotiations. But if China’s compliance with the WTO settlement process is a result of China’s socialization into international standards, why do we not see a simultaneous decrease in China’s adoption of WTO-inconsistent measures? What does China’s continuing reliance on industrial policy measures and ability to flout WTO rules reveal about the trade organization’s limits? In the relationship between the WTO and China, who is socializing whom and who is limiting whom?

In examining the pattern of China’s compliance with WTO dispute settlements, this article argues that China keep its industrial policies one step ahead of the WTO umpire by conveniently complying later with WTO dispute rulings. Under the WTO system, China does not hesitate to implement WTO-inconsistent regulations as a way to protect infant industries, develop strategic industries, and nurture national champions. Because the legal process at the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) takes months or even years, China continues to benefit from disputed policies while they are being reviewed and then can repeal them once the challenge succeeds. Also, DSB rulings mostly accomplish the removal of the offending measures rather than punishing the country that violated the provisions. Thus, it is in China’s best interest to adopt industrial policy measures first and remove them afterwards when they are in dispute. In doing so, China not only achieves its developmental purposes of putting those measures in place but also builds a reputation as a responsible WTO member by complying with the DSB rulings — a practice that I characterize as convenient compliance. Thus, China’s compliance reflects Beijing’s realpolitik calculation of achieving its economic development goals by navigating through the limitations of the WTO’s dispute-settlement process, rather than reflecting China’s socialization to international norms.

I also contend that multinational companies (MNCs) are not necessarily the main drivers of economic liberalization in China, as is often assumed in the literature. MNCs implicitly or explicitly support protectionist measures in China either because they fear retribution from Chinese government officials or because they benefit from gaining even small pieces of the ever-enlarging pie of Chinese trade. Global supply chain dynamics certainly complicate the issue of initiating trade disputes with China. First, interests between those economic actors who benefit from inexpensive Chinese imports and those who are hurt by them diverge. Second, interests also diverge between businesses without clear investment or contract ties with China and those with existing operations in China who are dealing with the country’s regulatory system on a daily basis. Firms’ form of market entry and their mode of operation in China often shape their attitudes toward initiating trade disputes with Beijing.

In an effort to substantiate China’s pattern of “convenient compliance,” I examine two recently completed trade disputes. First, I look at the dispute over China’s Measures Affecting Imports of Automobile Parts (DS 340), which the United States brought to the WTO in 2006 because of its adverse impact on American automobile parts exports to China. This is the first WTO case where China allowed the dispute to go through the full panel process. The second case I examine is China’s Special Fund for Wind Power Equipment Manufacturing (DS 419), where the United States and the European Union contested China’s subsidies for domestic wind turbine manufacturers that use domestic rather than imported goods.

I chose these cases as representative and indicative examples of China’s record of convenient compliance at the WTO. First, both have been viewed as positive examples of China’s removing contested measures upon the WTO’s final decision. Second, both the auto and the wind turbine industry have received strategic support from Chinese governments at various levels. Lastly, both cases show how China can continue to pursue its developmental goals by adopting other measures to replace the measures that were contested at the WTO. The auto case has continued to have an impact with the recent dispute the United States brought to the WTO in September 2012 regarding China’s subsidies for local automakers, and the wind case has had an impact on other green energy industries, such as solar panels.

This article begins by introducing my empirical puzzle and delineating the literature review on the WTO’s and MNCs’ impact on socializing and liberalizing China. I then explain my theoretical framework of convenient compliance and provide two trade dispute cases in the automotive and the wind turbine sectors. In so doing, I demonstrate how developing countries flout WTO rules, which in turn raises important systemic issues not only for the WTO, but also for free market principles in coping with the challenges raised by a large transitional economy like China.

Empirical Puzzle: What’s behind China’s Compliance to the WTO’s Dispute Settlement?

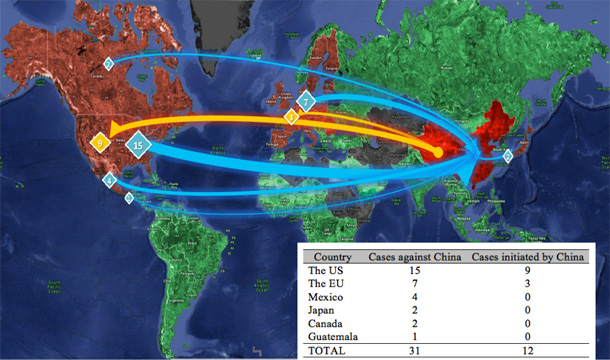

From its WTO accession till August 2014, China has participated in 155 disputes — 12 cases as a complainant, 31 cases as a respondent, and 112 cases as a third party. China is expected to be part of more trade disputes, given that it became the world’s largest exporter starting in 2009 and that the scope for trade friction increases as countries trade more. In fact, China was a party to only two of the 93 trade disputes at the WTO between its accession in 2001 and the end of 2005, but in 2009, China was a party to half of the fourteen new WTO disputes initiated in that year. And in 2010, China was involved in 26 of the 84 cases filed at the WTO. The United States accounts for the lion’s share of cases against China — as it has initiated 50 percent of the WTO disputes targeting China and participated in 70 percent of all WTO cases against China (which include disputes initiated by the EU). WTO members have mostly challenged Chinese industrial policy measures that favor state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and other domestic companies, discriminate against imports, and restrict foreign companies’ access to Chinese markets. The issues involved in these disputes include intellectual property rights, trading rights, and distribution services for products such as semiconductors, auto parts, and more recently renewable energy components. Over the years, China has shown “aggressive legalism” by being active in initiating disputes at the WTO, as it realizes its ability to use membership in the organization to defend its rights and interests. The eleven cases China has initiated at the WTO have so far targeted only two members — the U.S. (eight cases) and the EU (three cases). Nine of these cases have concerned trade remedies targeting anti-dumping, countervailing measures, and safeguard measures (Figure 1).

China’s compliance record in WTO dispute settlements has been quite outstanding. In the 11 completed cases where China was the respondent, Beijing has either reached agreement with the complainant over the disputed practices or has removed the measures that the DSB has found to be inconsistent with China’s WTO obligations. Of the eight completed cases where China was the complainant, Beijing has won four cases, received mixed rulings in another, and lost the remaining three cases. This record suggests that the WTO has been more effective in addressing countries’ trade concerns with China when compared with the era of bilateral trade negotiations. What does China’s increasing compliance with WTO procedures say about international institutions’ impact on transitional economies like China? And what about China’s continued reliance on industrial policies and discriminatory measures that contradict WTO principles and tilt the playing field against foreign business and imports?

The “liberalization group” of analysts in international relations and international legal studies expected China to accelerate its economic liberalization by preparing a level playing field for foreign companies and imports and increasingly comply with WTO rulings. First, according to these neo-liberal scholars, the WTO facilitates trade liberalization among nations by providing, monitoring, and enforcing rules on a multilateral basis. Its DSB enforces trade rules by evaluating a country’s potential WTO rule violations upon the request of other countries’ trade representatives. By entering the WTO, China abolished more than 800 of its trade-related rules during the first few months of 2002 and it had adopted, revised, or abolished an additional 2,300 pieces of legislation by the end of 2005.

Constructivist scholars, meanwhile, highlight international institutions’ ability to teach and socialize member countries to adopt international norms. According to this argument, China’s participation in the WTO leads China to incorporate WTO principles and terms into the Chinese government’s standard operating procedures and to mobilize domestic agents who share the idea of economic liberalization and compliance with WTO rules. These processes of learning and norm diffusion take place through the establishment of networks between domestic and transnational actors, or an “acculturation” process whereby a state “adopts the beliefs and behavioral patterns of the surrounding culture” through micro-processes of mimicry, identification, and status maximization. Scholars in international legal studies also believe that once countries join international legal agreements, they change behaviors and abide by those agreements out of the reputational concern of being considered a responsible member of the international community. However, these socialization and learning arguments would be more persuasive if we had witnessed China’s compliance with WTO rulings improve over time.

Figure 1. WTO Dispute Cases involving China (2001-August 2014)

Source: WTO, Dispute settlement: the map of disputes between WTO members, available at:

http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/dispu_maps_e.htm?country_selected=CHN&sense=e

Another group of scholars speak about how WTO rules are more constraining for developing countries than developed countries. According to Robert Wade (2003) and Linda Weiss (2005), WTO rules diminish developing countries’ room to maneuver by prohibiting industrial policy measures that developing countries may want to use in labor- and capital-intensive manufacturing industry. Most importantly, the WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMs) prohibits popular non-tariff barriers such as imposing requirements on foreign companies regarding local content, trade balancing, export performance, technology transfer, and domestic sales. On the other hand, other WTO rules permit — or at least do not explicitly prohibit — advanced countries to pursue more restrictive industrial policy in technology-intensive industries. For example, governments in developed countries can offer substantial support for venture capital financing of high-tech start-ups or provide strategic financing for pre-commercial technologies and product development. Thus, Wade and Weiss argue that developed countries craft WTO rules to best suit their current developmental trajectory, thereby putting developing countries at a systemic disadvantage...(Continued)

Center for China Studies

Center for Trade, Technology, and Transformation

Future of Trade, Technology, Energy Order

Rising China and New Civilization in the Asia-Pacific

Archives

![[ADRN Working Paper] Horizontal Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅰ)](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20240305162413775004648(1).jpg)

Working Paper

[ADRN Working Paper] Horizontal Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅰ)

Asia Democracy Research Network | 2015-05-13