※ This issue briefing has been published as a sequel to the ADRN Online Seminar titled “Democracy and New Generations.” Ian McAllister (Professor, The Australian National University), Woo Chang Kang (Professor, Korea University), Janjira Sombatpoonsiri (Research Fellow, German Institute for Global and Area Studies), and Ganbat Damba (Chairman of the Board, Academy of Political Education) presented the findings from precedent research and country cases. For more details of the event, please follow this link.

As we approach the second quarter of this century, millennials have firmly established themselves as the mainstream of society. The subsequent generation, often referred to as Generation Z, has taken their initial steps into the workforce. This trend is also evident in the political landscape of democratic countries in Asia. As time passes, the proportion of new generations among voters naturally increases, prompting political parties to consider their demands when formulating election strategies and policies.

Several Asian countries underwent democratization during the third wave of democracy in the 1980s and 1990s. This wave allowed the new generations in these countries to embrace democracy as an inherent value and norm. As democracy has progressed towards consolidation, it has not only become “the only game in town” but also “the only game in a lifetime” for the new generations. Furthermore, significant advancements in information and communication technologies have opened up new avenues for accessing information and taking into actions for political change. This has led to a widespread belief that younger citizens are generally more pro-democratic compared to their elders.

On the flip side, there are concerns that younger generations are relatively less engaged and apathetic towards politics. These concerns often stem from worrisome indicators such as lower voter turnout and occasionally result in a skeptical outlook on the future of democracy. Therefore, it has been increasingly important to delve into the perspectives of the younger generation on democracy, as well as the factors influencing their attitudes toward politics. This brief article reviews previous research conducted through survey analysis and examine youth participation in the Asian region as a case study.

Youth Demand for Substantive over Procedural Democracy

Young Asians exhibit several distinct attitudes compared to their elderly counterparts. Chu and Welsh (2015) conducted an analysis of the results from the third wave of the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS) and identified a noteworthy trend among Asian youth: their inclination to view democracy as a substantive concept. When asked to select the meaning of democracy from four values, “good governance” was the most frequently chosen, with 31 percent of respondents, followed closely by “social equity” at 28 percent. This suggests that 58 percent of respondents conceived of democracy in substantive terms, while the remainder placed greater emphasis on procedural aspects, namely “norms and procedures” (23 percent) and “freedom and liberty” (21 percent).

While the data also indicates that young generations consider all four principles important, the authors interpreted this as a sign that youth expect tangible outcomes from democratic governance. If democracies perform poorly in addressing issues such as economic recession and corruption, young citizens have the potential to become skeptical about democracy, even if procedural legitimacy remains intact.

A generation gap is also evident when citizens are classified based on their democratic orientation. In countries classified as “free” by the Freedom House Index, the proportion of “critical democrats” who embrace democratic values but are less supportive of their own democracy is relatively higher among younger cohorts. Among Generation Z, the percentage of critical democrats surpasses that of consistent democrats who uphold both democratic values and support for democracy. It is important to note that this correlation is partly contingent on the level of democracy, with the specific country playing a significant role as a variable. Nonetheless, the survey challenges the optimistic belief that youth are inherently more progressive.

Drawing from these indications, the lower enthusiasm of the younger generation toward politics may stem from a sense of inefficacy of their own democracy. This has led to a waning interest in traditional institutions of representative democracy among the new generations. They express less satisfaction with the functioning of democracy in their countries, compared to older age groups. ABS data reveals that they vote less frequently and are less engaged in politics through conventional means, such as joining political parties.

Still Lagging Youth Voting Participation and Electoral Barriers against Young Politicians

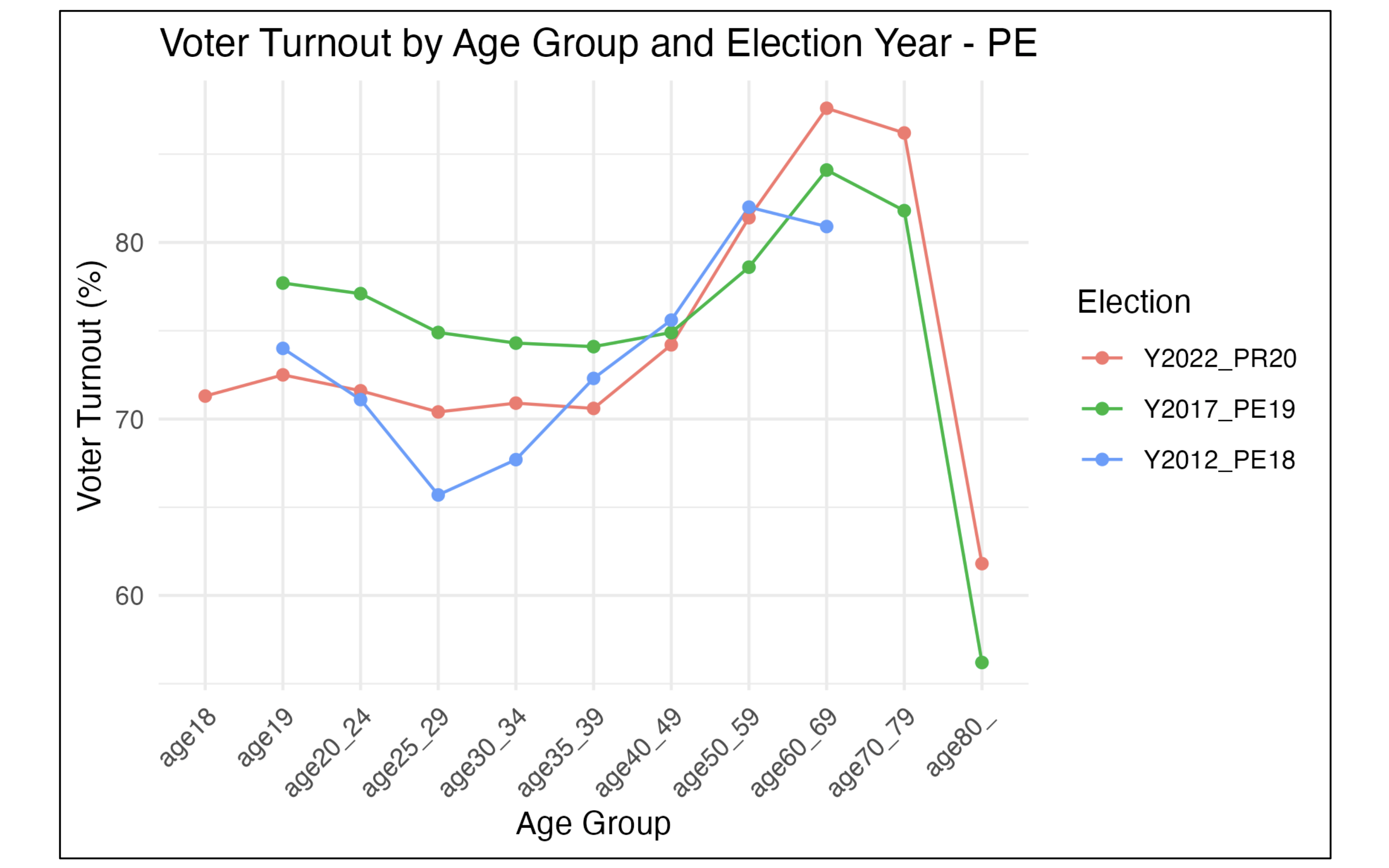

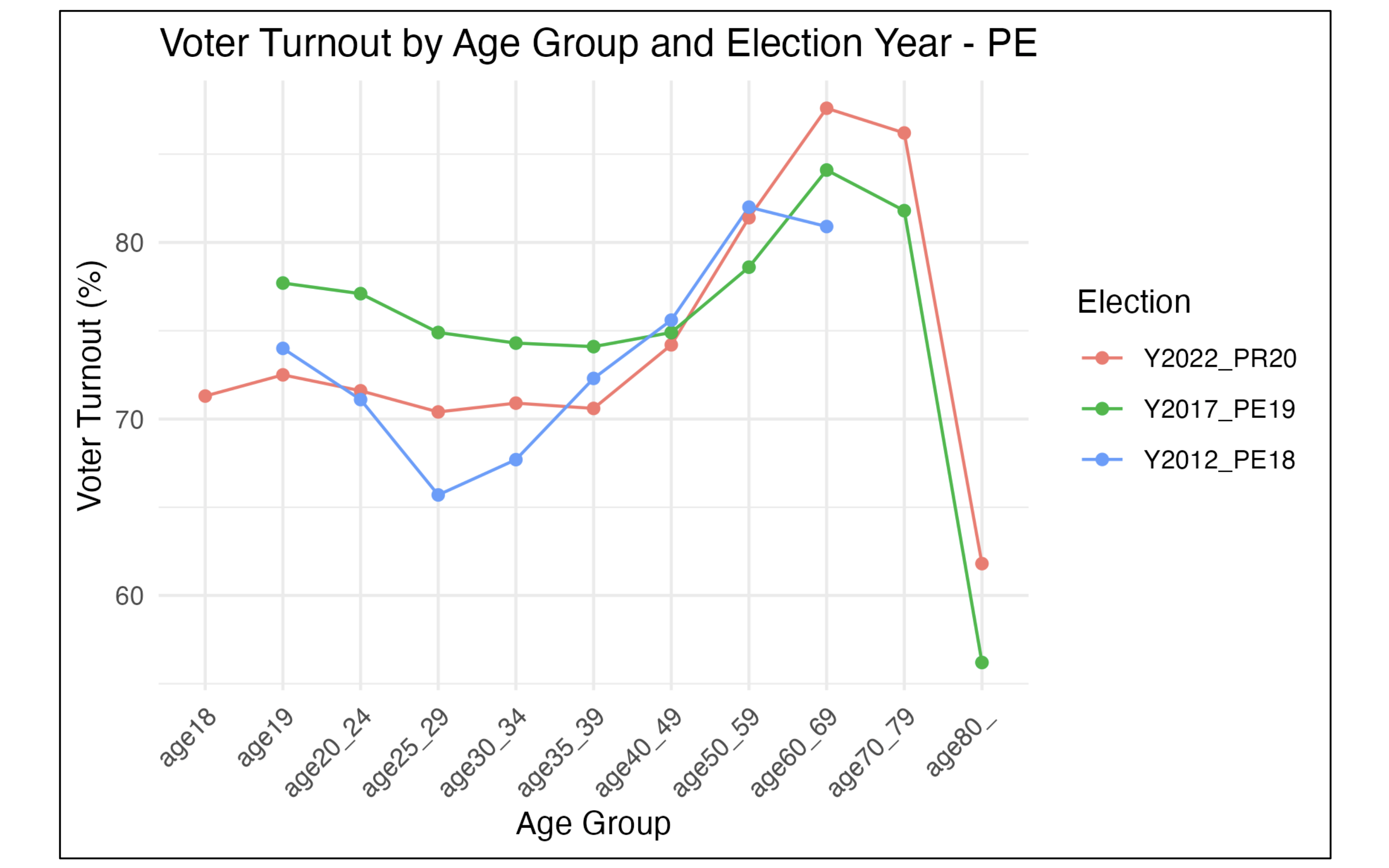

In recent years, South Korea has experienced significant dynamics within its democracy, marked by the impeachment of the president in 2017 and the successive change of government. Voter turnout for presidential, general, and local elections has seen improvement as the public felt stronger political efficacy. The youth generation was not an exception. However, their turnout rate is still the lowest among all cohorts. According to the National Election Commission (NEC), the turnout rates for individuals in their 20s and 30s in the 2022 presidential election were 71.0 percent and 70.7 percent, respectively. These figures are notably lower than the overall turnout rate of 77.1 percent and that of individuals in their 60s and 70s, which stood at 87.6 percent and 86.2 percent respectively. This age-related disparity in turnout is even more pronounced in general and local elections, where youth turnout falls further behind that of presidential elections.

This pattern of voter turnout mirrors the typical life cycle of a Korean citizen. Young voters aged 18 and 19 exhibit slightly higher turnout rates than those in their 20s and 30s. However, as young people enter the labor market, their turnout drops, only to recover when they reach their 50s and 60s, before declining again as health issues become a factor in their later years. This similarity suggests that the intense competition for a stable life with employment and housing may discourage young people from engaging in political matters.

Figure 1. Voter Turnout by Age Group and Election Year: South Korean Presidential Elections 2012-2022

South Korean youth are notably underrepresented in the realm of representative democracy. In the 2020 general elections, only 1.5 percent of candidates were in their 20s, and 6.1 percent in their 30s, while nearly half of the candidates were in their 50s. The underrepresentation of youth is even more pronounced among the elected representatives. In the same elections, out of 300 members elected to the National Assembly, only two were under 30, and thirteen were in their 30s. Given that the young voters under 40 constitute about a third of all voters, the gap between the demographic proportion of young voters and their representative proportion among elected politicians is big.

This gap is caused by the higher entry bar in politics against youth. Running for election in South Korea requires candidates to pay a deposit to the NEC with the amount varying based on the level of the election. For example, candidates for legislative elections in the district pay 15 million won, approximately 11 thousand US dollars. Additionally, there are campaign expenses to consider. Parties may cover their candidates’ deposits and campaign costs and the government reimburses these expenses based on the approval rate. Nevertheless, the competition to secure nominations from major parties is fierce, and new generations face challenges in mobilizing support due to their limited recognition and career experience compared to older candidates. These expenses pose significant barriers to youth participation.

Both the government and political parties have recognized the issue of lower youth participation and underrepresentation, and have made efforts to cultivate youth engagement and provide opportunities. Young voters have shown relatively greater fluctuations in their voting choices compared to older generations, who tend to align with conservatives and liberals. This has prompted major parties to focus their election campaigns on youth, pledging more financial support and featuring young politicians on the frontline of the campaign. However, most of these strategies lose momentum after the elections conclude. At the government level, each ministry in the cabinet has begun recruiting youth secretaries and advisory panel groups to incorporate youth voices into the policy-making process. Nevertheless, these entities have limitations due to their ambiguous authorities and lack of representativeness, as they are appointed by government officials rather than elected by young people.

South Korea’s example highlights the challenges in ensuring political opportunities for youth and how these challenges are linked to their lower participation. At the regional level, the participation of Asian youth in legislative bodies has been less active compared to youth in Europe or the Americas. When comparing the lower and single chambers worldwide, the average proportion of parliamentarians under the age of 40 in Asian countries was 16.01 percent, while European and American young parliamentarians accounted for 24.13 percent, respectively (IPU 2021). Ensuring youth representation in political processes is crucial for incorporating their perspectives and achieving sustainable and responsive outcomes (OECD 2021). Addressing the problem of underrepresentation is essential for enhancing the efficacy of democracy, as it contributes to younger citizens’ sense of involvement and revitalizes the sustainability of democratic norms and procedures.

Youth’s Expressive Politics and Potential as Agent of Political Change

Yet, the new generations possess the potential to serve as a driving force for political change. Chu and Welsh observed that the youth can be both disengaged and engaged, depending on the political context. ABS data has revealed that the young Asians are less active in the electoral process and formal methods of participation but have a relatively strong sense of their ability to participate in and influence politics. This self-evaluation is rooted in their characteristics, such as being highly educated, having easy access to sources of information, and actively expressing their thoughts through the internet and social networks. Their potential as a game changer at the critical political juncture is globally observed.

In Asia, youth in Thailand has recently demonstrated their capacity as a game changer. Young advocates for democracy have grappled with the challenges posed by the hybrid regime and have sought to mobilize reformative forces in recent years. The 2019 general election served as a catalyst for their efforts to achieve democratic governance. The Future Forward Party (FFP) embodied the aspirations of the new generation and rose to become the third-most-voted party with over six million votes. However, their political impact was short-lived as the party was dissolved by a ruling from the constitutional court, citing an illegal loan. This decision triggered mass mobilization led by young FFP advocates.

A series of massive protests unfolded between 2020 and 2021. Participants voiced their opposition to military rule and called for democratization and constitutional amendments. As the protests reached their peak in October 2020, social media users played a highly active role during the same period. The incumbent government responded to the movement with various and sophisticated repression strategies, including targeted harassment, surveillance of activists, as well as smear campaigns and online stigmatization.

Although the enthusiasm of the new generation expressed through protests has somewhat waned, party politics has continued to provide a platform for young citizens. The Move Forward Party (MFP), established in 2014, emerged as the successor to the dissolved FFP. Led by Pita Limjaroenrat, who is in his early forties, the MFP proposed reformative agendas targeting the military, the incumbent government, and even the monarchy. The party has relied on support from younger generation while striving to persuade the broader electorate to endorse for a better future.

In the 2023 House of Representatives election, the MFP secured 151 out of 500 seats, becoming the largest party in the House of Representatives. However, due to the presence of members nominated by the military government in the Senate, the MFP failed to form a coalition, and Limjaroenrat did not garner sufficient support to become the prime minister. As the institutions that restrict the possibility of regime change further discourage young advocates, the youth in Thailand stand at the crossroads between continued resistance and a sense of despair.

Conclusion

Young citizen’s perceptions, interests, and participation in democracy exhibit distinct characteristics compared to older generations and are sometimes adversely affected by social circumstances. It is essential to differentiate these characteristics from mere indifference or passivity.

Participation through online platforms and mobilization, which younger generations often engage in, can have a significant impact on their countries’ democracies and lead to change. However, it is representative democracy that ultimately determines most of the institutions and policies that affect the lives of future generations. To strengthen the influence of youth, political parties should encourage their younger members to pursue opportunities to run in elections and reflect the young generation’s perspectives into their policies. Additionally, it is crucial to lower the barriers for young politicians to enter the political arena.

The efficacy of democracy for young people cannot be improved solely by increasing the number of young representatives and public officials. It is vital to continually work towards enhancing the performance of democracy in terms of economic opportunities and social justice. Advocates of democracy should remember that the key to sustainable democracy lies in whether politics can effectively address the substantive concerns of the younger generation and deliver better outcomes. ■

References

Chu, Yun-han, and Bridget Welsh. 2015. “Millennials and East Asia’s Democratic Future.” Journal of Democracy 26, 2: 151-164.

Inter-Parliamentary Union: IPU. 2021. “Youth participation in national parliaments.” https://www.ipu.org/youth2021

OECD. 2021. Government at a Glance 2021. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en

■ Ganbat Damba is the Chairman of Board at the Academy of Political Education, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. From 1999 to 2010 he worked as an Executive director of the Academy. Since 2009 to 2017 he was an advisor to the President of Mongolia on research and a Director of the Institute for Strategic Studies of Mongolia. Since September, 2017-2021 he was an Ambassador of Mongolia to Federal Republic of Germany. He became Ph.D. in 2002 at the Academy of Science of Mongolia. He has published various articles examining democratization, democratic and authoritarian values, elections, political party development and on principles of foreign and security policy of Mongolia.

■ Hansu Park is a Research Associate at the East Asia Institute.

■ Typeset by Hansu Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | hspark@eai.or.kr

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Young Asians’ Attitude and Behavior Toward Democracy](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20230927183435373691294.jpg)

![[EAI Issue Briefing] Expectations and Challenges for Improved Relations with “Unfavorable” China under the Lee Administration: 2025 EAI Public Opinion Poll on East Asia](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2025070114329345217651(0).jpg)

![[EAI Issue Briefing] The Public Prioritizes a Future-oriented Cooperation over Resolving the History Problem in Korea-Japan Relations: 2025 EAI Public Opinion Poll on East Asia](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20250627164526777359170(0).jpg)