On August 12th, Malaysia held elections in six states, with voters from nearly a third of the country’s population eligible to vote. The results were a rebuke of Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s eight-month leadership. The conservative Islamist ethno-nationalist opposition Perikatan Nasional, comprised of the Islamist party PAS and ultra-ethnonationalist Malay party Bersatu led by former prime minister Muhyiddin Yassin, gained 61 seats out of 245 and 49% of the popular vote.

Given the unevenness of Malaysia’s post-COVID-19 economic recovery and the challenges of Anwar’s coalition ‘unity’ government, it is important to note that this coalition comprises his pro-reform Pakatan Harapan, his former political foe, the Malay nationalist United Malays National Organization (UMNO)-dominated Barisan Nasional (BN), and regional parties from Borneo. This alliance came together after the 2022 general election, which resulted in a hung parliament. Anwar’s preoccupation with promoting himself rather than focusing on policy programs made these election results somewhat expected. Little had been done to effectively communicate a cohesive program to the electorate or to shore up the legitimacy of a new friends-and-foes elitist government that holds the majority in parliament but remains unknown to the majority of voters. Instead, Anwar’s government relied on short-term populist initiatives that only served to fuel perceptions of seeking political security rather than leadership confidence in government.

Election Results: Anwar’s Weak Support and Growing Ethnic Divisions

The results show an across-the-board loss of support for Anwar’s unity government in all six states. In the Malay heartland states of Kelantan, Kedah and Terengganu, where the Islamist party PAS held power, it emphatically won two-thirds of the seats.

Table 1. 2023 Malaysia State Election Results

|

|

Total Seats

|

Anwar's Unity Government Seats

|

Seat Change from 2018

|

Opposition Perikatan Nasional Seats

|

Seat Change from 2018

|

|

Kedah

|

36

|

3

|

-9

|

33

|

13

|

|

Kelatan

|

45

|

2

|

-5

|

43

|

7

|

|

Terengganu

|

32

|

0

|

-10

|

32

|

10

|

|

Negeri Sembilan

|

36

|

31

|

-5

|

5

|

5

|

|

Penang

|

40

|

29

|

-6

|

11

|

10

|

|

Selangor

|

56

|

34

|

-11

|

22

|

17

|

|

Total

|

245

|

99

|

-46

|

146

|

61

|

In the three states on the more multiracial West Coast, Anwar’s government lost ground, losing the two thirds of support that Anwar’s party held as the incumbent state government in Malaysia’s richest state of Selangor.

The drop in seat numbers and the opposition’s gain of almost half the popular vote does not fully capture the ongoing shifts taking place in Malaysian politics. There are major political realignments taking place, including greater political polarization and a narrowing of the space to engage in democratic political reform.

First, the results show that the party that performed the worst was actually Anwar’s ally, UMNO, the Malay nationalist party that governed the country from 1957 through 2018. UMNO lost its power with its leader with its former prime minister Najib Razak mired in the 1MDB kleptocracy scandal. The current UMNO president is Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, Anwar’s deputy prime minister and close ally. His corruption charges shockingly dropped after the polls, despite the earlier findings supporting the need for prosecution and weeks of testimony. UMNO had 41 seats going into the state elections and emerged victorious in only 19 of the 108 seats (18%) that it contested. The erosion of support for UMNO started from 2004, but has reached the point that the party is no longer a national party, only holding power in the south and west of the country. With 26 seats in parliament, UMNO’s (and Zahid’s) support is deemed so vital for the Anwar government that he is now not facing criminal charges.

Second, not all of the parties in Anwar’s coalition Pakatan Harapan performed evenly. The Chinese-dominant Democratic Action Party (DAP) won 46 out of 47 seats (98%) it contested, while Anwar’s party Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) only gained 26 out of 59 (44%) seats contested and the progressive Islamist party Amanah won 8 out of 31 seats (26%). Pakatan was able to galvanize most of its traditional base of support, only losing turnout of some supporters. However, with the exception of one seat won marginally in Kelantan, it was not able to gain any electoral ground. The implication is that Anwar’s leadership has not been able to translate into political gains across the coalition, making Pakatan dependent on the support for the DAP.

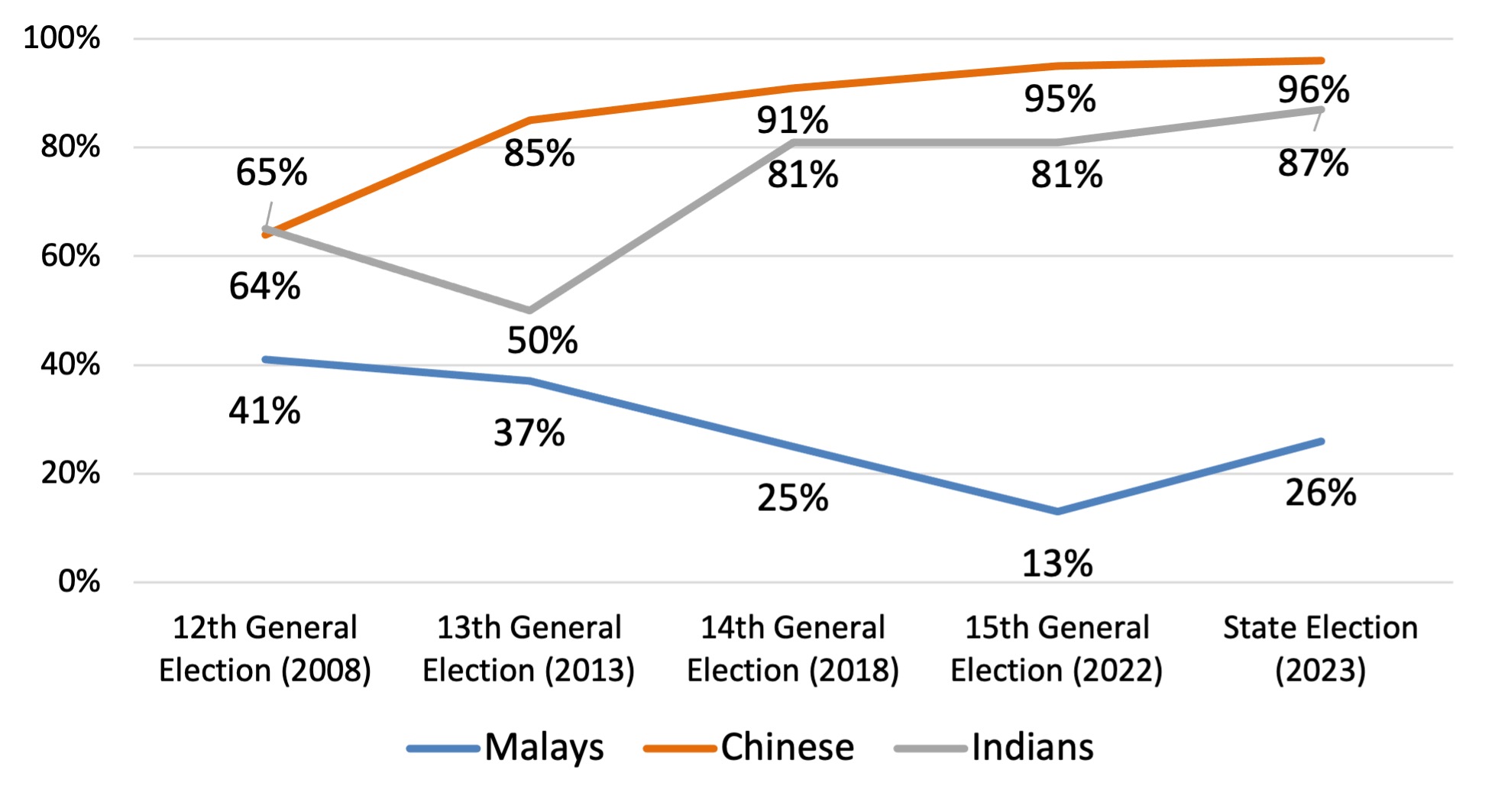

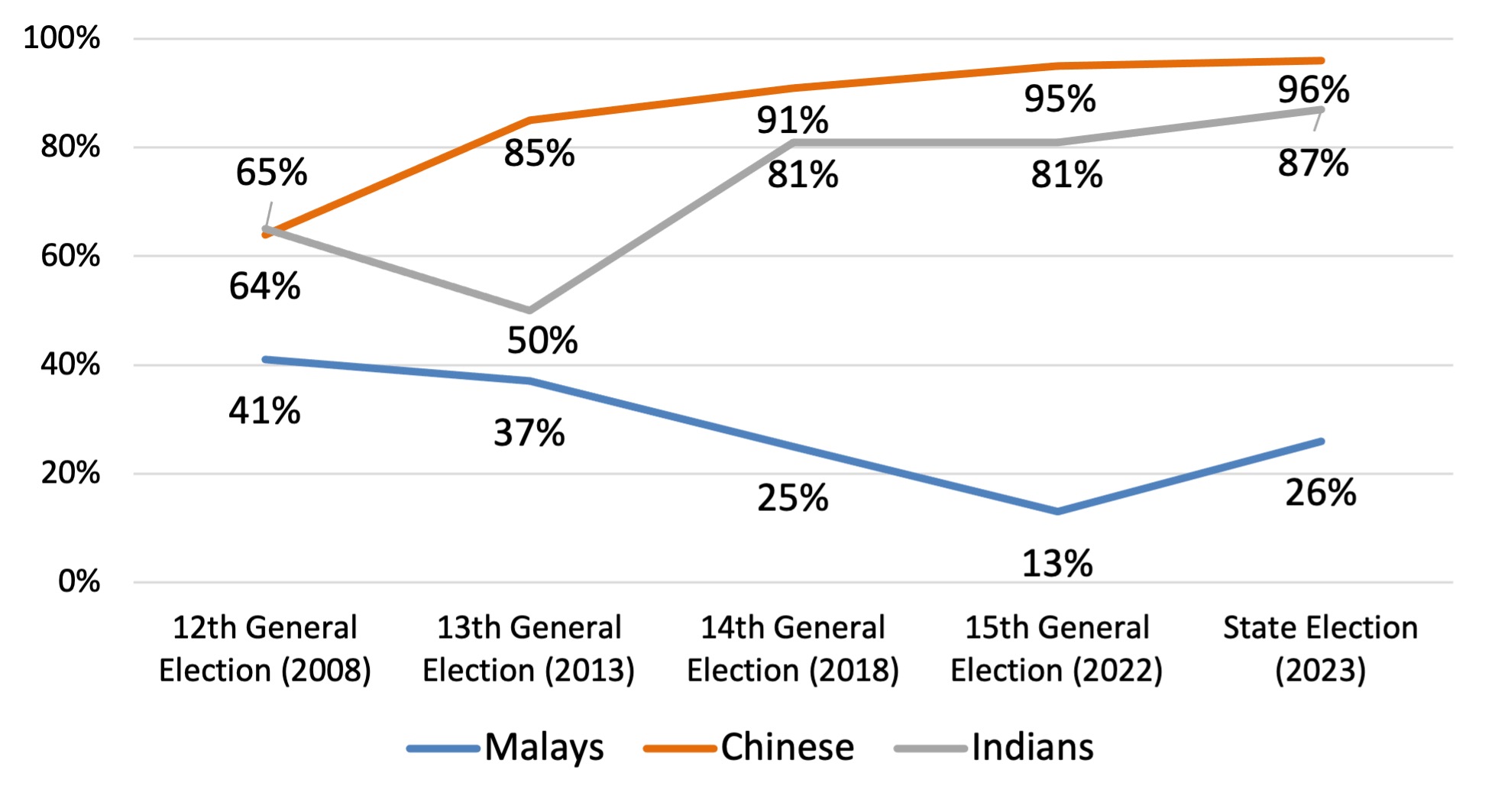

The reason for this lies with the third feature of the results, a widening ethnic polarization in voting. The unity government relied heavily on the support of Chinese Malaysians, an estimated 96 percent of those that voted and to a lesser extent Indian support at an estimated 87 percent. Meanwhile, the opposition gained a significant share of the majority ethnic group of Malays, estimated 73 percent of those voted. Perikatan’s increase in Malay support came largely from UMNO, where it captured nearly half of the party’s traditional support compared to the result in the 2022 November General Election. In that election, UMNO only managed to capture 26 of the seats out of 222 and 32 percent of the Malay vote. Anwar’s Pakatan relies on non-Malay support, even in its collaboration with UMNO/BN in the 2023 state elections, as shown in the chart below.

Figure 1. Estimated Electoral Support by Ethnicity for Pakatan Harapan Peninsular Malaysia, 2008-2023

The results show that ethnic differences in voting in Malaysia have widened and become more entrenched since 2008. The parties that were the most secure in the state polls are those traditionally on the more ethnic extremes of Malaysian politics, Islamist PAS and the Chinese-dominant DAP. With ethnic polarization in voting, Malaysia’s political realignment has shifted to one of polarized parties as well, with the middle ground hollowed out by UMNO’s political collapse.

Understanding the Results: Losing the Referendum

Explanations of the election results have centered on the campaigns, rise of conservative Islamist forces and shortcomings in Anwar’s leadership.

The Islamist opposition party PAS had made gains in the 2022 General Election, in its collaboration with Muhyiddin’s party Bersatu in a new branded coalition of Perikatan Nasional. PAS was able to build on its stronger social connections from religious schools, provision of social services, business ties and calculated campaign projecting itself as less ‘extreme’ than in the past. It was part of the federal government from 2020 through 2022 and part of a rebranded Malay ethnonationalist coalition, Perikatan Nasional, served to strengthen its electoral outreach.

PAS was able to extend its electoral gains in the state polls. What made PAS even stronger in the state polls was its ability to harness dissatisfaction with the economy, becoming a more acceptable opposition party. What occurred in the state polls was not a rise in conservative forces, but rather a normalization of them. A reliance on social media, calculated use of misinformation and emotional appeals further strengthened the Perikatan opposition.

With a focused campaign, Perikatan Nasional gained most of its support from political erosion of UMNO, a party that has corruption-tainted leadership that refuses to give way and give up access to the spoils of power. The relationship with UMNO president Zahid allows Anwar to hold power, as his coalition did not win its own electoral mandate in 2022. The relationship has also served to delegitimize both UMNO and Pakatan among their traditional core supporters. The electoral impact has been most evident for UMNO in the state results and among Harapan voters, especially with the post-election decision to drop Zahid’s corruption charges.

The results also indicate weaknesses in Anwar’s government. Their campaign for the state polls was ad hoc, lacking coordination and clear messaging, never controlling the political narrative. They underestimated political dissatisfaction. In Selangor, Malaysia’s richest state with PKR-led government, it lost its two-thirds majority. In fact, if it was not for the popularity of state leaders, the results might have been more even worse for Anwar, as the anger against his federal government was palpable.

The main weakness Anwar’s government faced was the weak economy, with high inflation and an uneven recovery from the COVID-19 economic contraction. With uneven competency in Cabinet, there has been a lack of coordinated policy reform, with measures that have been introduced poorly communicated. A focus of the government around Anwar’s persona rather than policy deliverables further undercut support. Anwar continues to have a trust deficit among large shares of the population, shaped by decades of political attacks he endured as a leader in the opposition from 1999.

Perikatan was effective in capitalizing on Anwar’s weaknesses through the campaign, making the election a referendum on him and his leadership.

Dampening Public Aspiration for Democratization Amid Polarization

Conditions were ripe for the opposition to gain ground. Part of this involves the legacy of COVID-19 on the economy and on the youth, who now comprise a large share of the electorate. Electoral reforms implemented in 2022 lowered the voting age to 18 and introduced automatic voter registration, bringing in large number of voters in their 20s and 30s into the electoral roll. Over a third of the electorate is under 30 years of age. Anwar’s government had yet to introduce substantive youth policies or programs where the young can recognize tangible benefits. Another part of this is the prominence of social media in Malaysia campaigns, especially TikTok which is a medium that has proven effective in capitalizing on anger and discontent.

What was striking in the 2023 state polls was a lack of messaging harnessing positive emotions compared to earlier polls. Calls for democratic reform have anchored support for Pakatan for decades, galvanizing voters through five general elections. Promises of hope and meaningful change were missing in these 2023 polls. With the election of pro-reform Pakatan Harapan government then led by Mahathir Mohamad in 2018 and its collapse in 2020, as well as the formation of the Anwar government in 2022 allied with the target of calls for reform, UMNO, the momentum for reform has precipitously slowed. Liberals hoping for meaningful policies to promote rights and inclusion have been repeatedly disappointed. For many Pakatan supporters, their vote was largely one against the opposition, more pragmatic and realistic, rather than one filled with the idealism of the past. This idealism is eroding with a focus on holding power rather than delivering promises to voters, the same voters that voted for reform for over two decades. More Malaysians do not believe that its leaders will deliver the meaningful reforms they voted for.

As such, an important shift is taking place in Malaysian politics; reform as an effective political mobilizer by parties is declining, contributing to the new political realignments and less trust in political parties across the political divide. Contestation over reform – strengthening checks and balances, more competent political institutions, electoral fairness, ethnic inclusion, decentralization and greater freedoms – has long anchored Malaysia’s political divisions, along with differences over race and religion. With reform no longer as prominent, identity politics have become even more salient, cutting into the social fabric of Malaysia’s ethnic relations.

The opposition Perikatan Nasional have positioned themselves to capitalize on this shift by combining race and religion in their messaging, articulating a neo-Malay nationalist agenda blended with political Islam. The opposition’s state polls campaign explicitly attacked the Anwar government for its collaboration with the non-Malay DAP and billed itself as the only legitimate representative for the Malay community. They articulated a more exclusionary Malay-only vision of governance on their campaign in the 2022 General Election, and claimed their opponents as lacking religious credentials. The Anwar government is being attacked for its supposed liberal policies of protecting the LGBTQ communities, allowing concerts and supposedly empowering non-Muslims, part of a heightened racialized culture war that has aimed to strengthen the opposition and put the Anwar government on the defensive.

What has happened, however, is that democratic political reforms are on the defensive in conditions with heightened racialized electoral polarization. Anwar’s government is relying more on its elite relationships, the levers of power against opposition leaders, with many facing legal charges, and is focused on holding power rather than on using power for concrete programs and new initiatives.

The implication is that Malaysia’s window to introduce meaningful democratic political reforms is closing. The 2023 state election results and aftermath, suggest that a government led by a leader who promised progressive reform to gain office is falling short in the delivery of promises and facing less favorable conditions to do so. This is a lesson many countries have learned before, but it nevertheless is a hard one for Malaysians seeking meaningful political change.

As Malaysia celebrates its 60th anniversary as a nation, the August state polls highlight that the challenges for nation-building remain as salient as they did decades ago; improving ethnic relations, reducing polarization, developing substantive policies to address inequalities and promote growth. At the same time, the hope for change and better governance is strong, with an electorate more demanding and confident in its aspirations. Reformasi may not yet be garnering traction among elites, but it continues to remain alive in a society looking for a stronger Malaysia in the years ahead. ■

■ Bridget Welsh is currently Honorary Research Associate with the University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute Malaysia (UoNARI-M) based in Kuala Lumpur. She is also a Senior Research Associate of the Hu Feng Center for Eats Asia Democratic Studies of National Taiwan University and a Senior Associate Fellow of the Habibie Center. She specializes in Southeast Asian politics, with a focus on Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore and Indonesia. She is committed to fostering engagement, mutual understanding and empowerment.

■ Typeset by Hansu Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | hspark@eai.or.kr

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Beginning of the End of Reformasi? Malaysia’s August 2023 State Polls](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2023092111628385503451.jpg)

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Europe’s Democracy Catch-22](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2024072614919379354954(1).jpg)

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Mongolia’s Electoral Reform and the State Great Khural (Parliamentary) Elections](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2024071923404138697271(1).jpg)