![[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅲ)](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250428171032795173098.jpg)

[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅲ)

| Working Paper | 2025-02-25

Asia Democracy Research Network

Active citizen participation in democratic decision-making?through elections, political parties, media, and civil society?is vital for ensuring government accountability. To assess the gaps between vertical accountability institutions and their practical implementation in Asia, the Asia Democracy Research Network (ADRN) conducted a comprehensive study. As part of this initiative, the East Asia Institute (EAI) published a series of working papers examining cases from Japan and Nepal. These papers explore the evolving role of civil society in fostering participatory political culture and underscore the importance of effective election management and strong political parties to safeguard electoral integrity.

In 2022, Asia Democracy Research Network (ADRN) selected horizontal accountability by the ability of state institutions to hold the executive branch accountable, and vertical accountability through elections, parties and citizens’ participation, as the requirements to accomplish robust and sustainable democracy in Asia.

Against this background, ADRN published this report to evaluate the current state of the trends and trajectories of vertical accountability in the region by studying the phenomenon and its impact within countries in Asia, as well as their key reforms in the near future.

The report investigates contemporary questions such as:

● To what extent are elections free, fair, and inclusive, and multi-party in practice?

● To what extent are political parties unrestrained in their foundation and activity?

● How effective does the media provide diverse political perspectives?

● To what extent do citizens voluntarily engage in CSOs, operated without interference?

● To what extent are citizens free to express their views without fear of suppression?

● What should be done to improve the state of vertical accountability performance?

Drawing on a rich array of resources and data, this report offers country-specific analyses, highlights areas of improvement, and suggests policy recommendations to fulfill methods of vertical accountability in their own countries and the larger Asia region.

Vertical Accountability in Japan’s Governance:

Impact of Public Conception and Its Changes

Maiko Ichihara[1]

Institute for Global Governance Research, Hitotsubashi University

Japan is experiencing a major political fund scandal. It is aligned that the Abe and Nikai factions within the governing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) failed to report a significant portion of income from political fundraising parties. The total amount is estimated to be approximately 800 million yen (approximately USD 5.5 million) over the five-year period from 2018 to 2022. As of January 2024, a lower house member Yoshitaka Ikeda had been arrested, and the Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office was reported to be considering prosecuting the treasurers of the two factions (NHK 2024-01-13).

While the Abe and Nikai factions together possess about 140 Diet members, only two have thus far commented on the case in public. It has been reported that the leadership of the factions has asked their members not to speak publicly about the case. This indicates a lack of accountability in Japanese politics.

Given the lack of enthusiasm among individual Diet members to engage with the public on this issue, the government’s approach to political reform seems somewhat tepid and superficial. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has taken the initiative of establishing a political party reform body within the LDP. However, an investigation revealed that ten of the 38 members of that body were affiliated with the Abe faction (NHK 2024-01-11). Kishida is criticized for his reluctance to implement meaningful reforms.

This scandal demonstrates a weak accountability in Japanese politics. Why ’did the faction members not raise this issue voluntarily? Why have they been refraining from talking about the case to the public, although they are elected officials who should abide by the law? In sum, what are the reasons for the lack of vertical accountability in governance in Japan? This paper argues that, while freedom of the press and of speech is well protected in the country, weak political participation of citizens, or weak exercise of “positive liberty,” fails to hold politicians, the party, and the government accountable.

1. Governance in Japan

In Japan’s governance, the bureaucracy has historically held significant influence over policy creation and implementation, with citizens expected to adhere to these policies.[2] Although the political landscape changed under the Abe adm?nistration, which strengthened the power of the cabinet secretariat over the bureaucracy, the centrality of the bureaucracy’s role returned under the Kishida adm?nistrations. The legislature’s lack of sufficient expertise and knowledgeable personnel has contributed to the bureaucracy’s continued dominance. Each Diet member in Japan possesses only two to three staff, whereas each American congress member has about 40. In addition, by conducting its politics of influence peddling until the mid-1990s, the LDP had established patron-client relations between politicians and citizens (Kobayashi 1997, Chapter 7; Kono and Iwasaki 2004).

From the perspective of society, Japanese tend to refrain from challenging the state on matters that they perceive as patronizing. Instead, they demonstrate a reluctance to engage in political participation, relying on the government to address collective action problems in the public sphere. Because of such an attitude towards political participation, the number of people with a political party affiliation is relatively low. The International Social Survey Programme study of Citizenship conducted in 2004 revealed that only less than 5% of respondents specified their political party affiliation “when asked which party” they typically support. This is a clear contrast to the United States, where over 40% of respondents specified their political party affiliation in the same research. Although the United States shows an exceptionally high percentage of individuals with political affiliation compared to other countries, North European and other Anglo-Saxon countries also had about or more than 10% of respondents specifying their party affiliations (Gibson et al. 2004, “Party Affiliation”). In comparison to other developed democracies, the lack of interest in political participation is distinctive in the case of Japanese citizens.

Rather than engaging in political processes and contributing to the resolution of collective action problems, Japanese citizens tend to expect and depend on the state. Compared to their interest in policy outputs, their interest in inputs is substantially weaker (Murayama 2003; Neary 2003). The Japanese population demonstrated a lack of interest in political participation in post-WWII period. The general population has historically demonstrated a lack of motivation to influence political processes. Instead, they have tended to rely on the government as a “charitable parent” who provides protection to its citizens, as articulated by Japanese philosopher and political activist Osamu Kuno (Kuno 1970; Yatsuhiro 1980, 6, 45-46). In light of these observations, the state-society relations literature of comparative politics and the domestic politics literature of international relations have consistently categorized Japan as a strong state, a statist country, or an elitist democracy (e.g., Katzenstein 1978; Katzenstein 1985; Risse-Kappen 1991).

1.1. Inactive Civil Society and Low Civil Liberty

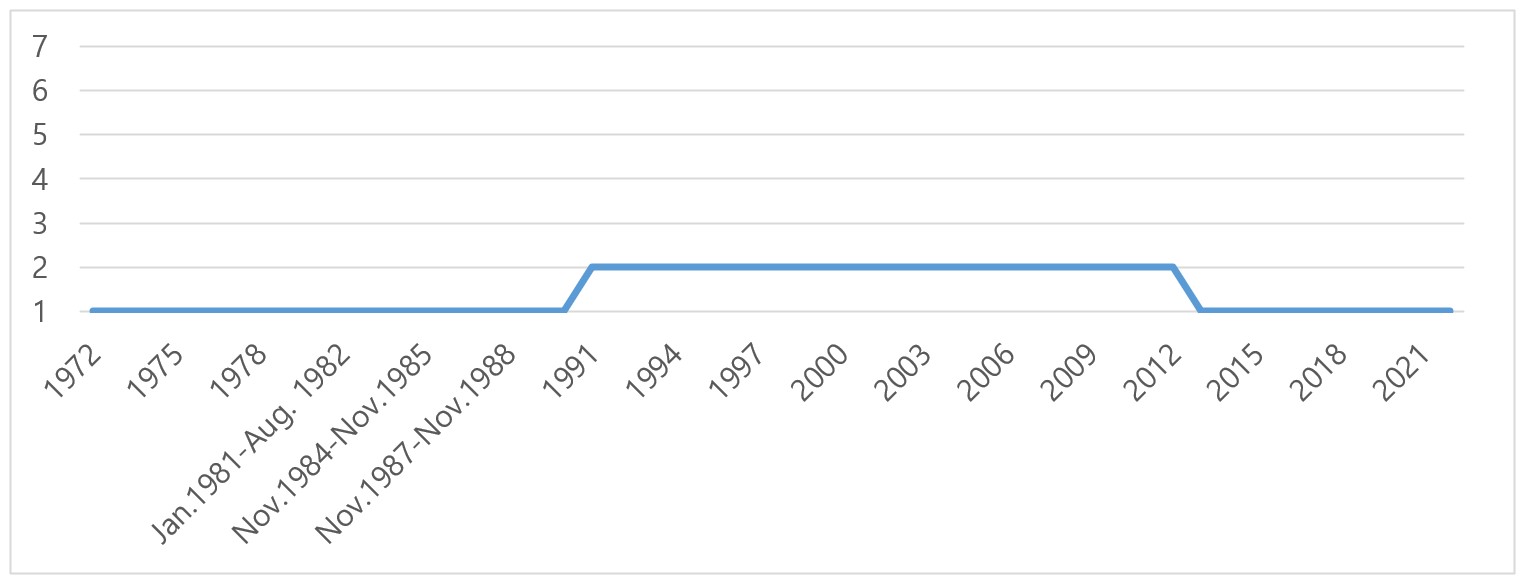

Robert Dahl argues that two dimensions are necessary for a country to be a democracy, or “polyarchy” in his term: public contestation and participation (Dahl 1971). There has been a notable level of public contestation in Japan since the conclusion of the Second World War. Despite the LDP’s nearly 40-year tenure between 1955 and 1993, the context was one of freedom of elections. Although the party conducted a politics of influence peddling during its years in office, citizens exercised their freedom to criticize the government, holding demonstrations and contesting in elections. Since Freedom House started collecting data on political rights and civil liberties in 1972, Japan has consistently scored either 1 or 2 out of 7 (with 1 being best and 7 being worst) on civil liberties (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Japan’s Civil Liberty Scores, 1972–2022

Source: Freedom House n.d.

While Dahl measures political participation based on suffrage, citizens’ political participation can also be measured by the existence of a vibrant civil society from the viewpoint of the civil society literature (Tocqueville 1969; Coleman 1988; Putnam, Leonardi and Nanetti 1993). Participatory democracy is a systеm in which civic associations play an active role in addressing collective action problems in the public sphere. It regards citizens not only as subjects to be governed, but also as governors, influenced by communitarianism, where the common good is considered ’the behavioral principle of the people.

However, citizens are not necessarily active in participating in politics and solving collective action problems in all democracies. Italy serves as an illustrated example. Scholars such as Edward Banfield and Robert Putnam have posited that a political culture of vertical personal relations can impede the flourishing of civil society (Banfield 1958; Putnam, Leonardi and Nanetti 1993). This seems to apply to the case of Japan as well.

The type of liberty exercised by the Japanese seems to affect state-society relations. In order to satisfy the two requisites of democracy which defined by Dahl, different types of liberty are necessary. For the exercise of public contestation, the concept of negative liberty, as defined by Isaiah Berlin, is essential. Negative liberty can be defined as the absence of limitations or interference from others. Public contestation may occur at various scales, from boycotts and strikes to demonstrations. Such actions are feasible when the guarantee of liberty from external influence is in place. On the other hand, in addition to negative liberty, positive liberty is a prerequisite for political participation. This is the liberty to engage with others, form agreements with them, and let oneself and others obey certain limitations, which cannot be attained through the mere exercise of negative liberty (Berlin 1958).

The Japanese people tend to only exercise public contestation or negative liberty, but they often lack the will to participate in political activities, which would constitute positive liberty. What factors have contributed to this phenomenon? An insight into this phenomenon can be gained from an examination of the Japanese understanding of the concept of the public (see, for example, Sasaki and Kim 2002; Yamakawa 1999).

2. Concept of the Public in Japan

As Jürgen Habermas observed, the concept of the public has undergone a transformation within Western culture. In feudal societies during the medieval period, the concept was used to express high social status or power. With the advent of the modern state, the public concept came to be used as a synonym for the state, as states expanded their adm?nistrative functions. However, as citizens’ economic activities became increasingly distinct from those of the state, the public concept came to encompass the citizenry (Habermas 1991). Additionally, Hannah Arendt defines the modern public sphere as relations among citizens (Arendt 1973).

In contrast, the concept of the public in Japan has remained largely unchanged over time. As was understood in the feudal systеm, the term “public” continues to be used to refer to those at the pinnacle of the social hierarchy in Japan. From the introduction of the public concept in Japan until the present, the term has been used to refer to a variety of figures, including lords, emperors, dominators, heroes, warlords, and bureaucrats, depending on the assumed hierarchy. In contrast, the term “private” has historically been used to refer to subjects and common people (Kim 2002, i). While the term “public” is subject to interpretation depending on the assumed hierarchy, the very concept of the public itself has remained consistent. Yoshiko Terao explains the genesis and etymological origins of the public concept in Japan as follows:

The Japanese word “oyake [(public or公)]” originally meant “great house,” which obtained the reading when the words “公” and “私 [(private or I)]” were brought from China. Then “公” and “私” rooted representing structural relations which function to support the feudal systеm during the Edo period. In the Edo’s feudal systеm, the shogunate was the “公” and feudal clans were “私,” while feudal clans were the “公” and vassals were “私” in their relations. Such systеm was embedded into the very bottom of the feudal systеm as can be seen in the word “奉公” [which means “apprenticeship” but writes as “contribution to the public”]. When comparing this structure to the public/private relationships of the West, Western public/private basically do not have hierarchical relations but were considered to constitute different spheres, while “公” was always positioned higher in the relations between “公” and “私,” and was considered to have higher values. Public as the main players in the public sphere of Europe and America is a group of individuals who is in charge of the public and are rational. They are the group of citizens who can be rational in their dialogues with rational others in the public sphere. “私” as first-person pronoun was established in the latter half of the medieval period, and differing from “我 (I),” “私” as a humble term taking a back seat to the others as a “公” cannot be an existence to have momentum to claim and justify its existence and thinking (Terao 1997, 135. Square brackets were added by the author).

Due to this understanding of the public as those at the apex of the hierarchy, the actors engaged in governance within the public sphere are perceived as exclusively state actors. As Terao points out, while the “general public” in English tends to have the connotation of sovereign members, “koshu (公衆)” as its Japanese translation does not have such a connotation, but it simply denotes people (Terao 1997, 136). As a result of this understanding of the public concept, Japanese citizens have typically refrained from engaging in political participation, asserting their rights only when these are contested. As posited by Hiroshi Minami, a Japanese psychologist, “selfhood is asserted in Japan usually only from the viewpoint of selfish individual benefits, not from the viewpoint of autonomous individual dignity being free from the interference of authority” (Minami 1953, 40). In other words, citizens are regarded as voicing their opinions not to fulfill their civic duty of participating in public governance, but rather as people who are not responsible for it.

Japanese citizens tend to have little interest in making inputs in politics and public policy (Murayama 2003). This makes a contrast when compared to citizens of other Western countries in providing input through avenues such as advocacy and lobbying. The number of NGOs with an advocacy function is relatively limited in Japan, as Robert Pekkanen points out (Pekkanen 2006). A survey conducted by the Johns Hopkins University group revealed a notable discrepancy in the ratio of service-providing NGOs to advocacy NGOs between Sweden and Japan. While the ration in Sweden was 1 to 1.07, in the early 1990s, it was significantly lower in Japan, at approximately 1 to 0.14.[3] The Japanese in general are not interested in the exercise of positive liberty or participation in politics. Japanese citizens rely on the authority for governance and tend not to take individual actions or participate politically (Kawashima 2000). Problems within the public sphere have historically been perceived as matters to be addressed by state actors.

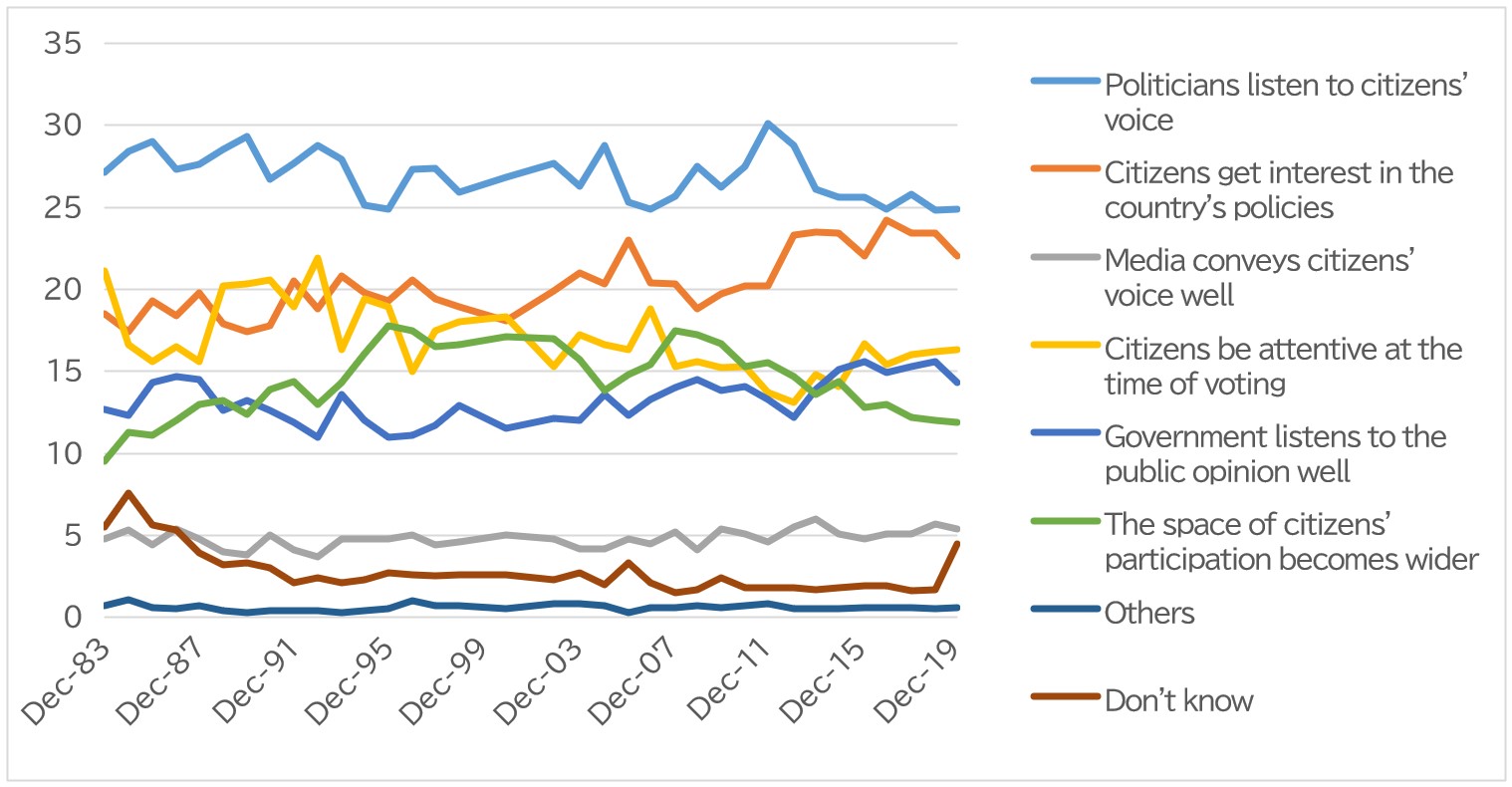

Figure 2 shows the prevailing opinion regarding the ideal means of reflecting public opinion in national policy. The predominant stance since the 1980s, indicated by the biggest percentage of respondents, has been in favor of politicians heeding citizens’ voices. This shows that the most popular method is one of passive engagement. In contrast, concerning active citizen participation in politics, the proportion of respondents who believe that “citizens should be attentive at the time of voting” reached its peak around the end of the Cold War, standing at approximately 20%. Since then, this figure has exhibited a downward trend. A similar downward trend is evident in the perception that “the space for citizens' participation should become wider,” with the proportion of respondents who expressed this view declining from approximately 17% in the late 1990s to below 12% by 2020.

Figure 2. Opinion Poll on How Best to Reflect Public Opinion in National Policy

Source: Cabinet Office, “Public Opinion Survey on Social Awareness (October 2024 survey).”

https://survey.gov-online.go.jp/living/202501/r06/r06-shakai/#sub15

This phenomenon is further compounded by a pervasive lack of awareness regarding the potential impact of political participation on shaping political outcomes. A survey conducted by the Asahi Shimbun in May 2021 offers illuminating insights to this matter. The survey revealed that 47% of respondents expressed a positive response when asked if their vote had the power to influence political developments, while a contrasting 49% expressed a negative view. During the years 2010 and 2011, when the Democratic Party of Japan was in power, there was a temporary increase in the sense of political efficacy, with 56% and 55% of respondents answering “yes,” respectively (Isoda et al. 2021). This suggests that the sense of political efficacy among the Japanese population as a whole is low. In a survey conducted by NHK in June 2022, 46.7% of respondents answered that they had “no expectations for politics,” and 42.1% answered that “even if I were to take an interest, politics would not change” (NHK 2022-06-15).

3. Changes and Three Enabling Factors

Despite the continued predominance of this political culture in Japan, there have been multiple indications of a shift in attitudes. The Abe Factor, digital technology, and the diversification of actors and activities have been the primary drives.

Before getting into the three drives, the impact of the New Public Management approach of relegating public roles to the private sector, adopted by US President Ronald Reagan and UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, on Japan in the aftermath of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake needs to be mentioned as the background enabling factor. The earthquake, which struck in January 1995, resulted in the loss of over 6,000 lives. However, the government's response was slow, as it took time for information to flow to the government and for countermeasures to be drawn up. It was primarily NGOs that carried out the rescue efforts quickly. Given this experience, the Japanese government passed the Act on Promotion of Specified Non-profit Activities the following year, which relaxed the criteria for recognizing the legal status of NGOs and allowed tax deductions for them. It was also around this time that organizations for vertical accountability such as the National Citizens' Ombudsman Liaison Conference and the Citizens' Information Disclosure Center were established.

On such basis, the number of advocacy NGOs working to increase political accountability increased during the first Abe adm?nistration. When Shinzo Abe took office in 2006, he took a series of actions that downplayed Japan's responsibility for past wars. A central tenet of Abe’s political philosophy, which he articulated through the slogan “breaking free of the postwar regime,” was the necessity of constitutional reform. This agenda encountered significant public opposition, leading to the formation of citizen groups across the country that sought to protect Article 9 of the Constitution, which stipulates Japan's renunciation of war. According to the Association for Article 9, the number of such groups exceeded 7,000 by 2008 (Japanese Communist Party 2008). These groups were active, holding demonstrations, public lectures, and distributing educational pamphlets (Creighton 2015, 128).

Pro-constitution groups diversified their activities, including opposition to the restart of nuclear power plants and the acceptance of the right to collective self-defense (Creighton 2015, 138). During the second Abe adm?nistration, Students Emergency Action for Liberal Democracy–s (SEALDs), an organization comprised of over 1,000 young individuals who expressed opposition to the Act on the Protection of Specially Designated Secrets and the security-related laws, carried out a wide range of advocacy and demonstration activities. These demonstrations, which were held repeatedly, attracted unprecedented numbers of participants, with some of them, according to the organizers' figures, drawing over 40,000 participants.

Advocacy in Japanese society shifted its main battlefield from offline to online after the SEALDs was disbanded in August 2016 due to the enactment of the security-related laws and the strong social opposition to their advocacy. In addition to the increased activity of speech on Twitter, online signature campaigns became more active. This shift in the political landscape was further evidenced by the rejection of six candidates who expressed criticism of the government's security policies by Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, in response to a proposal by the Science Council of Japan for new members. This rejection led to the initiation of an active petition campaign on change.org, aimed at safeguarding academic freedom (Ichihara, Misinformation and Polarization in Japan: The Suga Adm?nistration and the Science Council of Japan 2020). In the wake of these developments, various organizations have emerged, with a focus on enhancing the democratic transparency of the Japanese government. Prominent among these are No Youth No Japan and the Youth Democracy Promotion Agency, which are employing a combination of offline and online methodologies in their activities.

As we enter the 2020s, the combination of new actors and enablers has further invigorated civil society activities in Japan. This revitalization of civil society is motivated by the rise in protests by citizens against repressive moves by authoritarian governments in Asia. Large-scale protests against authoritarian rules and the violation of human rights have taken place since the end of the 2010s in Asia, spanning from the anti-extradition bill protests in Hong Kong, which led to the enactment of the National Security Law, the establishment of a military government through a coup in Myanmar, and the subsequent emergence of the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), as well as the Chinese government's repressive zero-COVID policy and the A4 Paper movement that opposes it. These protests have led to clashes between citizens and the governments in power. Consequently, notable number of pro-democracy citizens have moved to other countries, leading to an influx of these individuals in Japan. This influx has not only increased the number of activities advocating for freedom and human rights in their home countries from Japan, but also led to a rise in demonstrations questioning the collusion between these authoritarian governments and the Japanese government.

The scope of these activities has expanded beyond traditional advocacy work. Myanmar citizens have persisted in raising funds to support CDM's activities, and according to Yuki Kitazumi, Japan is the largest source of foreign funding for Myanmar's pro-democracy movement. Documentary films depicting individuals in Hong Kong and Myanmar who are advocating for freedom and human rights have been screened in cinemas nationwide, with full attendance recorded in most of the venues. Furthermore, when a singer who is banned from performing in China came to Japan to hold a nationwide tour, not only Chinese people in Japan, but also Chinese people who had traveled all the way from China to see the singer, gathered at the concerts, and the venues were packed to capacity all over the country. Exhibitions and other events that convey the current situation in each country are also being held in various places (Ichihara 2024).

These events are held one after another, and their success in attracting customers across Japan can be attributed to the presence of Japanese enablers. These enablers include Japanese activists who provide support and backing for the activities, as well as film distribution companies, cinemas and concert venues that actively screen these documentaries. The age range of these Japanese enablers is extensive, spanning from their 20s to their 70s.

4. Conclusion

In the context of Japan, the concept of vertical accountability has been found to be deficient, primarily due to the perceived weakness of civil society, which is in turn influenced by the public’s perception of the term. However, recent observations have indicated that an increase in the number of citizens' groups engaging in demonstrations, a revitalization of activities employing digital tools, and the emergence of novel actors and alterations in the form of activities. These developments suggest a gradual thickening of civil society.

The evolution of advocacy activities indicates a strategic adaptation by civil society actors to the political culture of Japan. In an era marked by societal fragmentation across various nations, it cannot be said that simply holding more demonstrations will necessarily benefit society. A more effective approach entails the development of activities that do not exacerbate societal division and instead foster empathy among individuals. The emergence of novel activities in the future holds promise as a catalyst for positive change. ■

References

Arendt, Hannah. 1973. The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Banfield, Edward C. 1958. The Moral Basis of a Backward Society. New York: Free Press.

Berlin, Isaiah. 1958. Two Concepts of Liberty: An Inaugural Lecture Delivered before the University of Oxford on 31 October 1958. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Cabinet Office. 2024. "Shakai ishiki ni kansuru yoron chosa (Reiwa 6 nen 10 gatsu chosa) (Public Opinion Survey on Social Awareness (October 2024 survey))."

Coleman, James S. 1988. “Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital.” The American Journal of Sociology 94: S95-S120.

Creighton, Millie. 2015. "Civil Society Volunteers Supporting Japan's Constitution, Article 9 and Associated Peace, Diversity, and Post-3.11 Environmental Issues." Voluntas 26: 121-143.

Dahl, Robert A. 1971. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Freedom House. n.d. “Freedom in the World: Country and Territory Ratings and Statuses, 1973-2023.” https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world (accessed November 18, 2023).

Gibson, Rachel, Shaun Wilson, and Markus Hadler. 2004. “International Social Survey Programme 2004: Citizenship.” Cologne: GESIS Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.11372 (accessed January 15, 2024)

Habermas, Jürgen. 1991. (translated by Thomas Burger, with the assistance of Frederick Lawrence), The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Hyden, Goran. 1999. “Governance and the Reconstitution of Political Order.” In State, Conflict, and Democracy in Africa, by Richard Joseph. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Ichihara, Maiko. 2020. Misinformation and Polarization in Japan: The Suga Adm?nistration and the Science Council of Japan. Asia Democracy Research Network Issue Briefing, 2020.

______. 2024. "Support Democracy in Asia from Japan." Shinano Mainichi Shimbun.

Isoda, Kazuki, et.al. 2021. "Ippyo ni Seiji ugokasu chikara "aru" 47%: Asahi yoron chosa (47% believe that one vote has the power to influence politics: Asahi poll)," Asahi Shimbun, May 3.

Japanese Communist Party. 2008. ““Kyujo no Kai" 7sen Toppa: Undo heno Futo na Kansho ni Kogi ("Association of Article 9" Counts More than 7000: Protesting against Unjust Interference in the Movement)." Akahata.

Johnson, Chalmers. 1982. MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Katzenstein, Peter J. 1985. Small States in World Markets: Industrial Policy in Europe. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Katzenstein, Peter J., and ed. 1978. Between Power and Plenty: Foreign Economic Policies of Advanced Industrial States. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Kawashima, Takeyoshi. 2000. Nihon Shakai no Kazokuteki Kosei (Family-like Structure of the Japanese Society). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Kim, Tae-Chang. 2002. “Hajimeni: Ima naze nihon ni okeru “ooyake” to “watakushi” nanoka (Introduction: The Importance of “Public” and “Private” in Japan Now).” In Kokyo tetsugaku 3: Nihon ni okeru ooyake to watakushi (Public Philosophy 3: Public and Private in Japan), by Tsuyoshi Sasaki, Tae-Chang Kim and eds. Tokyo: Tokyo daigaku shuppankai.

Kjaer, Anne Mette. 2004. Governance. Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: Polity.

Kobayashi, Yoshiaki. 1997. Gendai nihon no seiji katei (Political Process in the Current Japan). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Kono, Takeshi, and Masahiro Iwasaki. 2004. Rieki yudo seiji: Kokusai hikaku to mekanizumu (Politics of Patronage: International Comparisons and Mechanisms). Tokyo: Ashi Shobo.

Kuno, Osamu. 1970. “Niju yonenme wo mukaeru kenpo (Constitution Reaching Its 24th Years).” Mainichi Shimbun, May 1 and 2.

Minami, Hiroshi. 1953. Nihonjin no shinri (Psychology of the Japanese). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Murayama, Hiroshi. 2003. Nihon no minshusei no bunkateki tokucho (Cultural Characteristics of Japanese Democracy. Kyoto: Koyo Shobo, 2003.

Neary, Ian. 2003. “State and Civil Society in Japan.” Asian Affairs 34, 1 : 27-32.

NHK. 2022. "Seiji ishiki ni kansuru chosa: 3000 nin no riaru na omoi ha? (Survey on Political Awareness: What are the Real Thoughts of 3000 People?)" June 15.

______. 2024a. “Jimin “seiji sasshin honbu” de hatsukaigo: Kishida shusho ga tokaikaku ni ketsui (LDP’s “Political Reform Headquarters” Holds First Meeting; Prime Minister Kishida Determined to Reform Party).” January 11.

______. 2024b. “Seiji shikin jiken: Abe ha to nikai ha no kaikei sekininsha wo zaitaku kiso de kento (Political Fund Case: Treasurers of Abe’s and Nikkai’s factions to be considered for home prosecution).” January 13.

Pekkanen, Robert. 2006. Japan’s Dual Civil Society: Members Without Advocates. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Putnam, Robert D., Robert Leonardi, and Raffaella Y. Nanetti. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Risse-Kappen, Thomas. 1991. “Public Opinion, Domestic Structure, and Foreign Policy in Liberal Democracies.” World Politics 43 (July 1991): 479-512.

Sasaki, Tsuyoshi, Tae-Chang Kim, and eds. 2002. Kokyo tetsugaku 3: Nihon ni okeru ooyake to watakushi (Public Philosophy 3: Public and Private in Japan). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Terao, Yoshiko. 1997. “Toshi kiban seibi ni miru wagakuni no kindaiho no genkai (Limitations of Japan’s Modern Laws concerning Urban Infrastructure Improvement).” In Gendai no Ho 9: Toshi to Ho (Modern Law 9: Cities and Law), by Masahiko Iwamura, et al and eds. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. 1969. (George Lawrence trans., J.P. Mayer ed.), Democracy in America. New York: Perennial Classics.

Yamakawa, Katsumi. 1999. “Kokyosei no gainen ni tsuite (On the Concept of the Public).” Keynote lecture at the Annual Meeting of Nihon Kokyo Seisaku Gakkai (Public Policy Studies Association Japan).

Yatsuhiro, Nakagawa. 1980. Obei demokurashi heno chosen: Nihon seiji bunka ron (Challenge to Western Democracy: Japanese Political Culture). Tokyo: Hara Shobo.

[1] Professor, Graduate School of Law, Hitotsubashi University

[2] On the central role bureaucracy plays in Japan, see, for example, Johnson 1982.

[3] The number for Sweden is as of 1992, and that for Japan is as of 1995. The Johns Hopkins University, Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project.

Vertical Accountability: A Case Study of Nepal

Ujjwal Sundas[1]

Samata Foundation

1. Introduction

Following the People’s Movement of 2006, the country made significant strides towards a more democratic systеm of governance, with notable shifts occurring within the political landscape. All of the country’s major political parties began to emphasize the importance of “inclusion” as a goal. Nevertheless, the change has not significantly benefited the disadvantaged groups, including women, Dalit, Madheshi, Janajati, Muslims, and others. Overall, the level of participation of marginalized groups in the political process remains relatively low, despite the promises of inclusion in terms of caste and ethnicity made by political parties and subsequent governments.

Nevertheless, the people have finally identified a representative after two decades of absence, during which time they experienced a prolonged period of statelessness. Today, at least, the systеm is in place. The groundwork for a genuine democracy has been established. Nevertheless, it is imperative that the government at the local level be fully utilized to capitalize on the opportunities presented by the recent elections. The gradual approach towards an ideal democracy necessitates the integration of the people at the grassroots level with the state mechanism. There has been a notable discrepancy at the local level. The issues of good governance, gender and social inclusion, corruption, and impunity remain largely unaddressed.

At the present time, women and the most marginalized communities, such as the Dalits, are represented in the government. It is a mandatory requirement that each ward at the local level across the country accommodate a Dalit elected member. This is indicative of the progress that Nepal has made in its democratization process. Notwithstanding the altered context, the culture of representation, partnership, and participation remains significantly underdeveloped.

In order to ensure vertical accountability, it is essential to have in place horizontal accountability mechanisms like elections. These include independent and professional media, civil society, and other accountability mechanisms in between elections. In addition, the establishment of horizontal accountability mechanisms, namely the creation of robust and autonomous agencies, will serve to reinforce vertical accountability mechanisms (Lawoti 2019).

2. Rationale of the Study

In Nepal, following the abolition of the monarchy, the general public has been fully exercising their democratic right to choose their own leaders. Nepal, a federal democratic republic, has held significant elections in 2017 and 2022. In accordance with the Constitution, the country has adopted a mixed model of an electoral systеm. In consideration of the country’s context and a meticulous examination of the relative merits and drawbacks of the mixed systеm, the Nepalese electoral systеm incorporates both the First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) and Proportional Representation (PR) methods of voting. It is regarded as one of the most exemplary models of elections, exhibiting the principle of inclusion. Nevertheless, numerous challenges have arisen within the country, particularly with leaders failing to align their actions with the expectations of the electorate and major political parties engaging in a cycle of unstable coalition governments. The country faces a significant challenge in maintaining a stable government. Over the course of 16 years, Nepal has formed a coalition of parliamentarians on 12 occasions. The elected members have frequently switched between being in government and being out of government. The increasing influence of smaller political parties is contributing to a situation in which the formation of coalitions is becoming a determining factor in the political landscape, leading the country towards a state of prolonged instability.

Individuals assume governmental or parliamentary roles on numerous occasions, exploiting the provisions of the systеm. However, it is a crucial question in the present context to whom they are accountable. Those elected through both FPTP and PR appear to prioritize the interests of their respective parties. The election manifestos that are publicly declared right before the election are rarely fulfilled in practice. Individuals with criminal histories have been elected to government positions. Corruption and bribery have been pervasive within the political landscape. The tenets of the election code of conduct are grossly violated. The selection of an unsuitable leader, based on flawed input, has the potential to result in a lack of accountability to the electorate.

A multitude of actors are involved in the electoral process. However, the results of the election are not satisfactory, resulting in significant corruption during and after the electoral process. As a consequence of the lack of accountability of the entities and bodies associated with the electoral systеm in Nepal, a number of issues have become apparent, as outlined below.

Some political issues that have emerged include the formation of a predatory coalition between the ruling party and business houses, an unstable government, the formation of pre-election alliances among political parties, and a lack of effective institutional control over the electoral process. Similarly, there are some legal issues, including violations of the code of conduct during elections, an increase in corruption over the past 15 years (as reported by Transparency International Nepal in 2022), a lack of transparency regarding the rules, laws, and processes, delays in the formulation of laws and rules that have yet to be devised according to constitutional provisions, and a lack of transparency regarding the rules, laws, and processes.

3. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this research is to explore and analyze the accountability of political and legal entities to the general public, identify deficiencies in the electoral systеm in Nepal, and assess the challenges in fulfilling the aspirations of voters.

The following questions are of particular importance:

1. What improvements could be made to the electoral systеm in Nepal?

2. What factors contribute to the inability of elected officials to fulfill the expectations of the general population of Nepal? What obstacles do they encounter in the fulfillment of their responsibilities?

3. What factors contribute to the prevalent discontent expressed in the mainstream media regarding the performance of elected officials?

4. What forms of assistance do elected officials anticipate from the media and civil society organizations (CSOs) to maintain accountability to their constituents?

4. Literature Review

4.1. Government Structure of Nepal

The government of Nepal is structured into three tiers: federal, provincial, and local. The credit goes to the movement initiated by Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Center) which was later followed by democratic parties and other communist parties.

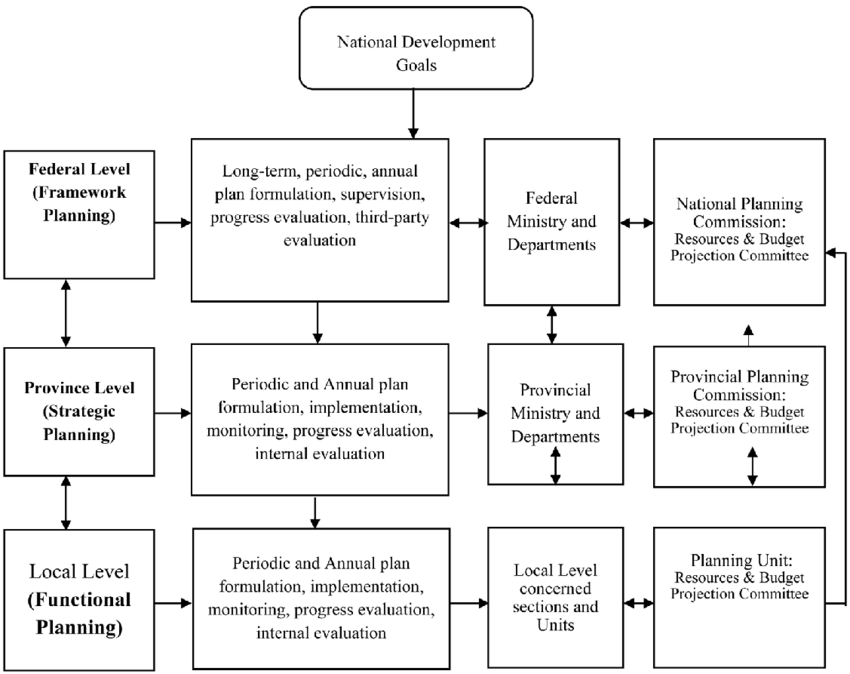

In accordance with the constitutional provision, the distribution of state power is allocated among the three-tier government systеm. The governments at the three levels are linked through the establishment of national development goals and objectives, which are set by the National Development Council. An intergovernmental relationship exists among the planning units at each level, both in terms of institutional structure and planning procedure. The distribution of state power among the three-tier government is defined by Article 57 of the Constitution.

The relationship between the three tiers of government is a two-way vertical one. This relationship exists between the federal government (FG), provincial government (PG), and local government (LG) and their respective planning entities during the different phases of the plan. This relationship can be further categorized as either a functional relationship or a resource-wise relationship. A defined relationship exists with regard to policy translation. In the preparation, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation of long-term, periodic, and annual plans, a vertical relationship shall be maintained between the planning entities of the FG, PG, and LG.

Figure 1. Relationship Between Three Tiers of the Government

Source: Taskforce Study Report Formulated by the NPC on 2016/09/25

The electoral systеm in Nepal reflects three key elements: the weight of public opinion, the consideration of popular interest, and the broad-based representation of social, economic, and political concerns of citizens. In addition to these functions, elections serve other vital purposes, including the selection of leaders, the conferral of legitimacy upon governance, and the establishment of accountability between the government and the electorate (Dahal 2001).

Nepal’s electoral systеm differs from the single-member-constituency systеm observed in the USA, UK, and Canada. In these countries, the candidate with the most votes in each constituency is declared the winner, even if this number falls below 50%. Nepal adheres to a mixed electoral systеm.

The Mixed Electoral Systеm (MES) preserves the proportionality benefits of the PR systеm while also ensuring that elected officials are assigned to specific geographical districts. Nevertheless, in instances where voters possess two ballots—one for the political party and one for their local representative—it remains uncertain whether the local representative vote is of lesser consequence than the party vote in determining the overall distribution of seats in the legislative body. Moreover, the MES can result in the creation of two distinct categories of legislators: those who are primarily responsible to and subservient to a constituency, and those who are drawn from the national party list and obedient to the party. Such a situation could have implications for the cohesion of elected political party groups.

The House of Representatives (HoR) is comprised of 275 elected seats, while the State Assemblies (SAs) have a total of 550 seats. The State Assemblies and the House of Representatives will be elected through a mixed electoral systеm, with 60 percent of representatives elected through the FPTP method and 40 percent through a systеm of PR that utilizes closed lists of candidates submitted by political parties. On Election Day, voters are thus required to cast four votes: one for an FPTP candidate for the House of Representatives (HoR), one for an FPTP candidate for their State Assembly (SA), one for the HoR party list, and one for the SA party list (source: IFES, November 2021).

5. Accountability of Government Bodies and Other Entities Towards the Voters

5.1. Election Commission

The Election Commission (EC) of Nepal is a constitutional election management body in Nepal. The Constitution of Nepal has established the framework for the EC in Section 24, Articles 245 to 247. The Constitution of Nepal has enshrined the competitive multiparty democratic systеm, adult franchise, and periodic elections as fundamental guiding principles of democracy. In accordance with the constitutional provisions, the Commission bears the responsibility for conducting elections at various levels—federal, provincial, and local bodies—in accordance with the prescribed electoral systеms (Election Commission of Nepal 2017).

The EC is responsible for conducting and supervising the national and local elections, as well as referenda on matters of national importance. They also make a final decision regarding the legitimacy of nominations for candidacy. The EC may delegate its authorities and duties to the Election Commissioner or the Government employee.

It is not feasible to conduct a fair and reliable election with the sole input of the EC. Therefore, in order to ensure the fairness and integrity of the electoral process, various judicial authorities have been established. Some of the aforementioned sectors are as follows:

5.2. Nepal Government

In accordance with Article 57 of the Constitution, the government is tasked with several responsibilities to ensure a clean, fair, and fearless election. These include creating a conducive environment for the election, finalizing election dates in coordination with the EC and political parties, and formulating laws to combat impunity and corruption. The government must also guarantee the safety of voters and candidates, support the Commission in enforcing the code of conduct, and ensure the safe and convenient transportation of senior citizens, individuals with illnesses, and persons with disabilities to voting centers. Additionally, it is responsible for coordinating with the EC to mobilize non-government sectors, as well as engaging election supervisors, media, and social organizations to properly manage and organize the election process.

A government lawyer has specific responsibilities both during and after an election and may be held accountable for fulfilling these duties. They are tasked with aiding and guiding law enforcement agencies in the investigation and prosecution of electoral crimes, ensuring all proceedings are lawful and supported by sufficient evidence. Additionally, they must provide support to plaintiffs in a tactful and effective manner. If a verdict is deemed unsatisfactory, it is the responsibility of the government lawyer to initiate an appeal in a higher court.

5.3. Parliaments

In order to ensure the timely and meaningful conduction of elections, it is incumbent upon parliamentarians to formulate the necessary policies and make the requisite amendments. Similarly, parliamentarians are expected to assess the performance of the EC and the government and provide constructive feedback, recommendations, and guidance as needed.

5.4. Political Parties

It is incumbent upon political parties to instruct their respective cadres to refrain from any form of intimidation, harassment, or unlawful influence exerted upon voters and candidates. Political parties should establish criteria for candidate nomination in accordance with existing legislation.

In collaboration with the EC, civil society organizations, and the government, political parties should implement training programs for their respective cadres to enhance their capacity for conducting fair elections. It is incumbent upon political parties to lend their support to the government in its efforts to control and punish those engaged in election-related crimes.

5.5. Election Supervisor, Civil Society and Media

Election supervisors, members of civil society, and media personnel carry significant responsibilities in ensuring transparency, fairness, and the timely dissemination of election results. The press should exert pressure on the relevant authorities to uphold the highest standards in these areas and assist government bodies in creating a safer environment that protects human rights for all. Collaborating with the EC and government entities, civil society is responsible for implementing voter education programs and ensuring that political parties and candidates adhere to the established election code of conduct. Additionally, they must provide necessary resources, training, and services to support the electoral process effectively.

6. Findings and Analysis

6.1. Uniqueness of Electoral Systеm

The two major elections held after the promulgation of the Constitution in 2015 are distinctive in that they are a mixed systеm (FPTP and PR with a 60:40 ratio). The principle of inclusion is reflected in the PR systеm at both the federal and local levels. The aforementioned reservations are intrinsic to the electoral systеm itself. The scope of the reservation is extensive, encompassing a diverse array of groups, including women, Dalits, Madhesi, Janajati, Muslims, and others. In the presidential, parliamentary, municipal, and ward levels, it is required that the chair and the deputy be of different genders.

A minimum of 33% female representation is required for nearly all formal parliamentary committees, ministries, and other official bodies.

6.2. Degree of Accountability

Members elected at the local level are more directly accountable to the public, whereas members elected at the provincial and federal levels have dual responsibilities: to their political parties and to the general public. It appears that elected members at the provincial and federal levels are more focused on the agenda of their political party and less focused on the needs of the general public. The parliamentarians are dedicated to their party leaders and are engaged in a competitive pursuit of securing an election ticket for the subsequent round, in the hope of pleasing the party leaders.

The party manifesto may initially appear to be quite attractive and in the public interest. However, maintaining a coalition in a multi-party systеm/government is a significant challenge. Therefore, the party manifesto is subject to dilution as a consequence of the greater influence exerted by the dynamics of the coalition.

7. Efforts to Promote Accountability

A number of donors and international development organizations have been providing support to the electoral systеm and the EC in collaboration with the Nepalese government since the introduction of federalism in Nepal. Immediately following the election, training is provided to elected members. A variety of international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and government bodies collaborate to conduct training sessions for elected officials with the objective of ensuring accountability to the general public.

The majority of parliamentarians and ministers do not engage in the training programs. Such individuals often exhibit a self-assured demeanor, suggesting a belief that they possess comprehensive knowledge on the subject matter. Such individuals tend to believe that their extensive political experience and understanding of the nuances of governance equips them with the requisite knowledge to address the needs of the general public.

The training and assistance provided encompass various initiatives aimed at strengthening electoral and governance processes. These include capacity-building programs for the EC, voter education programs, and legislative drafting. Additional training focuses on skills to mitigate conflict and foster collaboration, ensuring that elected officials and civil servants fulfill their responsibilities and remain accountable to the public. Furthermore, specialized programs are offered to empower women to actively engage with the Constitution (Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Adm?nistration 2021; Himalayan News Service 2018-02-18; NDI 2009).

7.1. Code of Conduct

The EC has made an election code of conduct for all voters and the candidates (Nepal Election Commission 2022). The code of conduct is disseminated to the general public and political party members through a series of training programs and via the election supervisors.

Some behaviors are overt and can be monitored and regulated, whereas others are covert and conducted surreptitiously. Adherence to the Code of Conduct is of paramount importance for elected officials, both during and after the electoral process. In the context of elections, a number of irregularities have been observed, including the induction of elected members, the use of bribery, the exertion of threats to influence candidacy and results, and the capture of polling stations. The tenets of electoral law are either disregarded or contravened. Campaigning programs often result in significant expenditures that exceed the limits set by the EC. Some candidates seek undue financial support from wealthy businessmen.

In some remote areas of Nepal, incidents such as intimidation and the consumption of alcohol in polling stations are not uncommon. In regions with challenging geographical features and limited transportation options, individuals with disabilities and the elderly may face difficulties in reaching polling centers, thereby hindering their ability to cast votes. Consequently, the number of votes cast for the selected candidate is reduced. The candidate(s) who are able to provide logistical support (travel, food, and accommodation) for the voters may have an advantage in the electoral process. Additionally, some villagers have been offered the waiver of their loans in exchange for casting their votes in accordance with the instructions provided.

Furthermore, the EC has been found to have some shortcomings. Some respondents indicated that the EC is not functioning in an autonomous manner. The dates of the elections are set by the incumbent government without any consultation or discussion with the EC. The financing of election security measures is not subject to sufficient regulation. The efficacy of voter education is undermined by its hasty adm?nistration in the period preceding the election. The incumbent government has been observed to deliberately initiate or approve development projects in the period preceding elections. In rural areas, security and order is not adequately maintained.

7.2. Continuous Political Party Rule and the Division of Power

The two major political parties have been in continuous power since 1990. The Nepali Congress (NC) and the Communist Party of Nepal (CPN) – United Marxist-Leninist (UML) have been in government, holding key ministries for the past 34 years. Even after declaration of Nepal as a republican country, they are still in power along with the Nepal Communist Party (NCP). The reason for this is that they are unable to secure an absolute majority (two-thirds) in the lower house. Such parties anticipate the outcome of elections and seek to form alliances in advance, with the objective of achieving the desired result. This has been the case since 2008.

Table 1. Prime Ministers of Nepal since 2008

|

No. |

Prime Ministers |

From |

Till |

Period of Month |

Political Party |

|

1 |

Girija Prasad Koirala |

28-May-08 |

18-Aug-08 |

3 |

NC |

|

2 |

Pushpa Kamal Dahal |

18-Aug-08 |

25-May-09 |

9 |

NCP-MC |

|

3 |

Madhav Kumar Nepal |

25-May-09 |

6-Feb-11 |

21 |

UML |

|

4 |

Jhala Nath Khanal |

6-Feb-11 |

29-Aug-11 |

6 |

UML |

|

5 |

Baburam Bhattarai |

29-Aug-11 |

14-Mar-13 |

19 |

NCP-MC |

|

6 |

Khil Raj Regmi |

14-Mar-13 |

11-Feb-14 |

11 |

Independent |

|

7 |

Sushil Koirala |

11-Feb-14 |

12-Oct-15 |

20 |

NC |

|

8 |

KP Sharma Oli |

12-Oct-15 |

4-Aug-16 |

23 |

UML |

|

9 |

Pushpa Kamal Dahal |

4-Aug-16 |

7-Jun-17 |

10 |

NCP-MC |

|

10 |

Sher Bahadur Deuba |

7-Jun-17 |

15-Feb-18 |

8 |

NC |

|

11 |

KP Sharma Oli |

15-Feb-18 |

13-Jul-21 |

41 |

UML |

|

12 |

Sher Bahadur Deuba |

13-Jul-21 |

26-Dec-22 |

17 |

NC |

NC: Nepali Congress, UML: United Marxist and Leninist, NCP-MC: Nepal Communist Party-Maoist Center

The government was dissolved on 12 occasions between 2008 and the present. In order to maintain a two-thirds majority coalition government, frequent changes have been made to both the cabinet and the arithmetic equations of political party members. The dissolution of a coalition government at the federal level has repercussions at the lower levels as well.

7.3. Significant Systеmic Corruption

Following the declaration of Nepal as a “secular, federal, democratic, republic nation” in 2008, a significant instance of systеmic corruption emerged. There has been a flagrant abuse of power. Those in positions of power, including ministers, parliamentarians, mayors, and high-level government bureaucrats, have been implicated in acts of corruption. Some have been incarcerated, while others are currently under investigation, and a few more are awaiting trial. The following is a list of significant instances of corruption that have occurred in Nepal since 2008.

Table 2. List of Significant Instances of Corruption since 2008

|

No. |

Major Scandals |

Approx. Amount (NPR) |

|

1 |

Gold smuggling |

N/A |

|

2 |

Fake Bhutanese Refugees |

288.17 million |

|

3 |

Lalita land scam |

N/A |

|

4 |

Omni scandal |

N/A |

|

5 |

Tax Embezzlement |

10.02 billion |

|

6 |

Budhigandaki Hydropower |

9 billion |

|

7 |

Printing press |

700 million |

|

8 |

CCTV scandal |

N/A |

7.4. Election Expense and Predatory Relations with Businessmen

EC guidelines limit campaign expenses to NPR 2.5 million (equivalent to USD 18,000) for General Assembly and NPR 1.5 million (equivalent to USD 10,800) for Provincial Assembly. Political leaders are seeking the support of businessmen in order to obtain the necessary funds, and in turn, the politicians are working in favor of the businessmen.

A former minister asserts that a minimum of NPR 50 million (equivalent to USD 360,000) is required to secure an election victory. He further states, “Our average five-year income would be approximately four million, and we believe that we must recover this amount during our tenure.”

7.5. Candidacy Nomination by Political Parties

The nomination of candidates by political parties is a common practice in Nepal, observed across the political spectrum, including among smaller and newer parties. In the case of FPTP candidates, nomination is principally based on the contribution of the proposed member to their respective political parties.

The formal process is as follows. Firstly, the district committees nominate members from each district and send the recommendations to the central committee. Subsequently, the central committee members finalize the list of candidates who compete through FPTP. However, in reality, the party president exercises ultimate decision-making authority in an autocratic manner. In addition, undue influences are exerted by neighboring countries with regard to regional politics.

7.6. Selection of PR Candidates

In principle, 110 members of parliaments are selected from Dalits, Janajatis, women and Madheshi communities by central committees of the respective parties. However, in contrast, influential party members, particularly those with the prerogative of the Party President, have been known to make decisions that result in nepotism and favoritism. For example, individuals from the elite and privileged classes and castes have been observed to occupy seats. For instance, in the case of the spouse of the General Secretary of UML, this individual has been elected as a parliamentarian under the PR systеm. From the Nepali Congress, a spouse of a prominent leader serves in the parliament through the PR systеm. Similarly, from the CPN (Maoist), a daughter and brother respectively hold the positions of mayor and speaker in the upper house.

Senior politicians themselves have opted for the PR systеm over direct elections, as it is a more cost-effective option for them. Rather than engaging in electoral competition, some individuals choose to make a financial contribution to the party in question. This can be described as a form of illicit procurement of seats in the PR systеm. Elected members assert that the financial expenditure incurred during the electoral process (FPTP) could potentially reach up to NPR 50 million per seat.

7.7. Political Manifestation during Election

The concept of accountability is not a mandatory legal requirement. In an interview, a former member of the Constituent Assembly observed that voters are not particularly concerned with election manifestos and are instead guided by political parties. He additionally stated that voters anticipate personal benefits from election candidates. Voters are less concerned with the policies and laws that elected members will enact for the general public and instead focus on the potential benefits they may receive from these elected members, such as employment or business opportunities. Additionally, a senior journalist posited that voters should establish deadlines and inquire of elected officials what actions they have taken to ensure accountability.

In the aftermath of an election, the gap between leaders and voters appears to deepen, giving rise to concerns regarding the quality of communication and interaction between the elected representatives and the electorate. This phenomenon has been observed to engender frustration among voters who, despite having previously enjoyed positive relations with their elected representatives, have found themselves facing diminished communications in the period following their electoral winning. The ease with which individuals can engage with their leaders becomes increasingly challenging, leading to a gradual erosion of trust and a perception among the public that leaders become unreachable.

7.8. The Advent of Novel Perspectives

“The PR model is financially burdensome, as it necessitates greater representation and resources, which consequently increases expenses for the government,” asserted senior leaders from the NC and UML. The influence of minor political parties has resulted in a disproportionate amount of power, which has led to a lack of decision-making progress. The practice of political representation is being misused by political parties. Those who have held prominent positions of authority on numerous occasions are frequently recommended for PR seats. “Those who are concerned about the potential consequences of losing elections under the FPTP systеm are also seeking PR tickets,” states a professor of political science and former chief of the Central Department of Political Science. There have been calls from within the major political parties (such as the NC and the UML) for the removal of the PR systеm and the adoption of a full FPTP systеm. In contrast, the CPN-UML has expressed support for a full PR systеm and direct election of the state head.

8. Various Factors for Poor Accountability

Vertical accountability is subject to various factors that contribute to its weakening, apart from the influence of leaders themselves. The deterioration of accountability in the country is influenced by numerous factors, including the actions of law enforcement agencies, such as security forces mobilized during elections; government officials responsible for updating voter lists;the Election Commission (EC) officials who sets the standards for election process; the tendency of politicians seeking support from businessmen; the conduct of politicians; the role of the media; and the influence of CSOs. Subsequently, the entire accountability of elected members is impacted.

8.1. Factors Related to Election Management

State of Security Arrangement: Security concerns represent the most significant challenge during election periods. During the election, EC mandated an efficient security arrangement, which included the deployment of a temporary police force. However, these forces were unable to fully fulfill the required security duties. During elections, tensions between opposing parties escalate, leading to physical altercations in election camps and, in extreme cases, the cessation of voting. The deployment of adequate security personnel is contingent upon the magnitude of the electoral district. This Underscores the necessity for the mobilization of temporary police forces. Additionally, security measures should be assured for senior citizens and individuals with special needs.

In 2022, the local people of Ward No. 4, Deuchuli Municipality, Area No. 1 of Nawalpur District set alight the ballot box, which contained 702 votes. A similar incident occurred in Area No. 6 of Deurali in Kavre district, where the ballot box was destroyed by local people. These incidents exemplify the challenges in maintaining peace during elections in Nepal, where disorder is a common occurrence.

Error and update delay on voter’s list: Errors in the voter list have been observed due to the untimely updating of voter data, which results in the list reaching voting centers after the designated time. This has led to instances where voters, particularly those residing in distant locations, have been unable to attend voter education programs, consequently causing errors in the voting process. Consequently, A significant number of previously cast votes have been subsequently canceled, suggesting a deficiency in the efficacy of the government sectors responsible for maintaining accurate data.

The consequences of this malfunctioning systеm are evident in the occurrence of multiple instances of individuals casting votes on behalf of absentees. In some cases, these votes were cast as many as ten times. This phenomenon can be attributed to the failure to update the voter list in a timely manner, which may result from changes such as migration, death, or simply absence. The repercussions of this malfunctioning systеm are far-reaching, as it has led to significant tensions among the contesting parties.

Negligence of the Election Commission: The EC has demonstrated negligence in its evaluation of political parties’ eligibility for new registration, as evidenced by the case filed against Mr. Rabi Lamichhane, the party chair of the Rastriya Swatantra Party, who was questioned on his nationality.

Despite the established rule prohibiting the provision of money or invitations to feasts during elections, political parties have been observed distributing money and organizing feasts for the public. Furthermore, it is not allowed to paste pamphlets and posters of candidates on the walls and poles during campaign, but no political party has followed this regulation. Buses and trucks are overloaded by the campaigners, in violation of the standard set by the EC. The EC’s approach to addressing these violations has been limited, as it has not taken any action against the parties.

Poor voter education: Voter education is a crucial aspect of electoral processes, yet the efficacy of voter education programs in Nepal remains questionable. The state has allocated NPR 50 million for voter education, yet the outcomes have not been satisfactory. In the April 2022 elections, EC allocated 15 days for voter education program and tried to implement an electronic voting systеm. However, due to inadequate planning by the relevant sector, the e-voting systеm was not widely adopted, resulting in the cancellation of numerous ballots.

From 1991 to 2017, there was an increasing trend in the nullification of electoral results, primarily attributable to inadequate voter education. In 1991, 322,000 votes were annulled, while in 2017, the figure reached 1,568,191. A similar trend was observed in the 2022 election, where a total of 9,644 votes were annulled in the Jumla district alone.

This tendency is primarily due to the complexity of the voting slips and the subsequent inability of voters to comprehend the instructions provided. This persistent issue underscores the necessity for comprehensive voter education to enhance voter awareness and ensure the integrity of electoral processes.

8.2. Factors Related to Political Party

Undue Pressure from Political parties: During elections, major parties have been observed to engage in actions that may be considered as misuse of power, often employing various strategies to maintain their position of authority. The apprehension of losing the election has led to a pervasive trend of manipulating the general public through deceptive means. Constitutional provisions have granted local governments increased authority; however, local political parties and leaders have been found to deliberately delay the delivery of voter lists, thereby impeding the execution of voter education programs and resulting in the cancellation of numerous ballots. Party cadres have been found to exercise undue influence over election results, contributing to widespread manipulation.

Local governments, purportedly entrusted with the responsibility of good governance, have been embroiled in various scandals. This has further eroded public trust.

Pre-election Alliances: Political parties have been observed engaging in practices that have the potential to create confusion among voters. These practices include the establishment of alliances with competing parties prior to the election, often accompanied by the dissemination of promises and threats, which can disorient voters who adhere to specific political ideologies. This phenomenon has the capacity to impede the autonomy of voters in selecting their leaders.

Furthermore, political parties tend to delineate their prospective electoral areas, thereby influencing the electoral landscape. These parties employ mathematical strategies to secure a majority of seats in the government or, at the very least, maintain their presence in government by holding key ministries. In doing so, they frequently neglect their own manifestos and engage in negotiations with competing parties, arriving at mutual agreements that allow them to remain in government. This practice has been observed in Nepal since 1992, when the country underwent an election under a constitutional monarchy. The formation of pre-election alliances effectively renders the general public captive. For instance, the Nepali Congress party, which had previously entered into an alliance with the Communist Party, compelled voters to cast their ballots for the latter.

Support sought from businessmen: Political parties seek support from businessmen, while businessmen, in turn, await opportunities to influence legislation in a manner that benefits their interests. As political parties receive financial and logistical support from these businessmen, leaders are compelled to compromise on various issues, often favoring the interests of businessmen. It has been observed that individuals involved in heinous crimes have been acquitted. Notably, Presidents have been known to exercise amnesty towards affluent and influential gangsters with who they share a connection with political parties.

In Nepal’s context, a symbiotic relationship exists between corporate entities and politicians, which intensifies during electoral periods. As the election gets over, politicians appear to prioritize fulfilling their pre-existing agreements with corporate entities, often at the expense of smaller and less influential businessmen.

Corruption during and after the election: Recent news outlets have reported a surge in high-profile corruption cases; however, there has been a paucity of action in response. The cases in point are the alleged involvement of high-level leaders in gold smuggling and “Lalita Niwas” land grab scam, that has remained stagnant. This phenomenon suggests that the nation’s legal apparatus is being undermined by influential actors.

The systеmic corruption manifests in the formulation of policies that are rife with loopholes, subsequently legitimized by the very same laws. In this case, corruption is occurring in a rather subtle manner. The majority of these kinds of irregularities often go unnoticed, which has a detrimental effect on the country’s economy.

8.3. Factors Related to Candidates and Electorates

Elected members to declare their wealth possession: EC has established a systеm mandating that all elected officials are required to disclose their wealth following their assumption of public office. As outlined in Article 50 of the Corruption Detail Act 2049, an elected official is obligated to reveal all wealth and properties held in their name and on the name of any family members within 60 days of assuming their public position. The Commission for Investigation of Abuse of Authority is authorized to initiate proceedings at any time if it finds that a person has accumulated wealth in an unnatural manner.

While the Code of Conduct promulgated by the EC requires all winning candidates to disclose their wealth immediately upon assuming their positions, high-level leaders have not complied with this code.

Notably, as of April 2022, the Mayor of Kathmandu Metropolitan City, Balen Shah, the Deputy Mayor, Sunita Maharjan, and the Mayor of Bharatpur Metropolitan City, Renu Dahal, had not submitted the election expense details. These incidents give rise to numerous suspicions.

It is important to note that political parties are only permitted to engage in election campaigning for a maximum of 90 days. Following the promulgation of the code of conduct by EC during the election period, the government is obligated to cease all activities, including the promotion and transfer of government employees, in order to avoid any undue influence on the electoral process.

Unnecessary Expenses by Candidates for Election Purposes: The EC has stipulated the following expense standards for local governments during the 15-day election campaign.

Table 3. Expense Standards for Local Electoral Campaign (NPR)

|

|

Mayor and Deputy Mayor |

Other Members |

|

Metropolitan Cities |

750,000 |

250,000 |

|

Sub-metropolitan Cities |

550,000 |

200,000 |

|

Municipality |

400,000 |

50,000 |

|

Rural Municipality |

350,000 |

- |

According to the 2022 EC guidelines, election expenses should be conducted in the 10 areas of procurement of voter lists, transportation of campaign materials, fuel, meeting expenses, mobilization of party cadres, and conduction of representatives.

However, the election code of conduct is not being followed properly, and candidates are not adequately briefed about election expenses. In the previous electoral cycle, a total of 1,233 candidates were in contention; however, only 574 of these candidates have submitted comprehensive election expenses reports.

Irrational decisions of parties on candidacy for FPTP and PR: PR systеm is not implemented according to its fundamental principles. Originally conceived as a means of integrating individuals from marginalized communities into the domain of mainstream politics, the PR systеm has become subject to misinterpretation. Women from affluent backgrounds and rich businessmen in the name of Madheshi have been incorporated into the PR systеm. In contrast, under the FPTP systеm, political parties select candidates who are popular but also possess the financial resources to influence voters.

False promises made by the candidates: Leaders pledge to prioritize initiatives such as education, healthcare, infrastructure development, potable water provision, electricity, and employment. However, upon assuming office, these commitments are often disregarded, as the focus shifts towards partisan agendas, leading to a perceived breakdown in accountability for these pledges. This phenomenon can erode public trust in leadership.

Disconnect between Elected members and general public: In the context of remote regions in Nepal, effective communication emerges as a salient concern. A significant proportion of the population appears to be uninformed about the candidates and the process of casting votes. Campaigners often neglect to provide comprehensive information, instead focusing on showcasing a select group of candidates and symbols. This oversight results in the general public lacking a comprehensive understanding of political parties and candidates, rendering them susceptible to external influences. Individuals in positions of authority, often wielding power and cunning, strategically manipulate the perceptions of the general populace in remote regions.

8.4. Factors Related to Media and CSOs

Media’s Bias: The preponderance of news outlets is under the sway of the major political parties, and the journalists who work for these outlets often lack integrity. They disseminate information that favors certain political parties, and in many cases, the facts and figures that the public needs are either distorted or concealed. This results in voters being under- or misinformed.

Given that the media is considered the fourth main organ of the state, it is essential that it functions ethically and impartially. The Nepali public places significant trust in various media sources. FM radios, in particular, have gained significant popularity across the country. During elections, the media has the potential to play a pivotal role in educating the public, preventing rigging, controlling violence, and assisting voters in making informed decisions. However, the effectiveness of this potential is hindered by the presence of bias in media outlets, which hinders the promotion of good governance.

Role of Civil Society Organizations: Civil society can play a significant role in the process of selecting leaders. One way that civil society can contribute to this process is by ensuring that the general public is informed about their rights, the vision of political parties, and the importance of fair elections. Civil society organizations can also function as a watchdog during elections. Unfortunately, many of these organizations are actually controlled by the major political parties, which can result in election manipulation. For instance, in Nepal, many of the CSOs that were established after 1992 were initiated by UML party, followed by the Nepali Congress.

9. Conclusion