![[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅰ)](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250428162723795173098.jpg)

[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅰ)

| Working Paper | 2024-12-23

Asia Democracy Research Network

Active citizen participation in democratic decision-making processes?through formal mechanisms such as elections and political parties, as well as the roles of media and civil society organizations?is crucial for ensuring governmental accountability. The Asia Democracy Research Network (ADRN) has undertaken research to evaluate the existing gaps between vertical accountability institutions and their implementation across the region, while identifying necessary reforms for the future. As part of this initiative, EAI published a series of working papers analyzing cases from India, Indonesia, Mongolia, Pakistan, South Korea, and Thailand. The research highlights the critical importance of safeguarding the autonomy of electoral management bodies and political parties, as well as fostering active citizen participation and oversight to prevent governance from being dominated by authority alone.

In 2022, Asia Democracy Research Network (ADRN) selected horizontal accountability by the ability of state institutions to hold the executive branch accountable, and vertical accountability through elections, parties and citizens’ participation, as the requirements to accomplish robust and sustainable democracy in Asia.

Against this background, ADRN published this report to evaluate the current state of the trends and trajectories of vertical accountability in the region by studying the phenomenon and its impact within countries in Asia, as well as their key reforms in the near future.

The report investigates contemporary questions such as:

● To what extent are elections free, fair, and inclusive, and multi-party in practice?

● To what extent are political parties unrestrained in their foundation and activity?

● How effective does the media provide diverse political perspectives?

● To what extent do citizens voluntarily engage in CSOs, operated without interference?

● To what extent are citizens free to express their views without fear of suppression?

● What should be done to improve the state of vertical accountability performance?

Drawing on a rich array of resources and data, this report offers country-specific analyses, highlights areas of improvement, and suggests policy recommendations to fulfill methods of vertical accountability in their own countries and the larger Asia region.

Electoral Accountability in India:

Emerging Discourse in the Historical Context

Kaustuv Kanti Bandyopadhyay[1]

Participatory Research in Asia

1. Introduction

India’s democracy has thrived over the past 77 years since the country gained independence from British colonial rule. Its foundation has been fortified through distinct contributions of various pillars, including the parliament, the judiciary, political parties, media, civil society, and most significantly, the citizens. Despite concerns and uncertainties from various corners, the framers of the Indian Constitution and the Constituent Assembly made a pivotal decision by embracing universal franchise. This move opened up the opportunity for every adult Indian to participate in voting and select their representatives.

India embraced constitutional federalism with a unitary structure featuring two tiers of government – the union government and state governments. Subsequently, in 1992, two significant constitutional amendments introduced a third tier of government as an institution of local governance, with Panchayats for rural areas and Municipalities for urban areas. India’s parliament is bicameral, consisting of the House of People (Lok Sabha, also known as the Lower House) and the House of States (Rajya Sabha, also known as the Upper House). The representatives of the House of People are directly elected by the people from their respective constituencies, while the members of the House of States are elected by Members of Parliament and State Legislatures. Members of the Lok Sabha are elected for a five-year term, while members of the Rajya Sabha serve a six-year term, with one-third of the members retiring every two years. Both houses are represented by Members of Parliament (MPs). Each Indian state has an elected State Legislative Assembly (also known as Vidhan Sabha), and its members, known as Members of Legislative Assemblies (MLAs), are directly elected by the people. Some states[2] also have bicameral legislatures with an Upper House known as the Legislative Council. Members of Legislative Councils are elected by representatives of local governments, state legislatures, and others[3]. In the context of local governance, members of the three-tier[4] Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) and Municipalities[5] are directly elected by the people. Additionally, in specific states, mayors or chairpersons of the municipalities may directly elected by the people.

This paper primarily focuses on recent political discourses concerning electoral accountability at the national level. However, it also delves into the historical context of these issues, thus offering readers a more comprehensive understanding of the evolving nature of the discourse. The first section of the paper discusses the extent of citizen participation in elections with a specific focus on the participation of two prominent demographics: women and youth. These constituencies have a significant impact on electoral outcomes in recent elections. It also illustrates the substantial contribution of civil society in promoting electoral participation. The second section explores the functioning of the Election Commission of India, which is responsible for the supervision and management of national and state elections. Furthermore, the paper addresses the controversies surrounding the use of Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs). The subsequent section examines the proposed simultaneous elections of national, state, and local governments, as well as the potential implications for the federal nature of Indian politics. This followed by a section addressing the political party and election campaign financing, a consistently controversial issue in Indian politics. In light of the aforementioned discussions, the paper draws conclusions and proposes crucial policy recommendations.

2. Citizen Participation in Elections

The voter turnout, or electoral participation of citizens, is a key indicator of the strength of a democracy. India is frequently designated as the world’s largest democracy due to the significant number of people who exercise their right to vote as granted by the Indian Constitution. Given the country’s diverse population, encompassing different genders, religions, castes, ethnicities, geographies, languages, abilities, and more, the specific breakdown of participation has been a topic of interest for scholars. This section will explore the historical context of overall voter turnout, with a specific focus on the participation of women and youth.

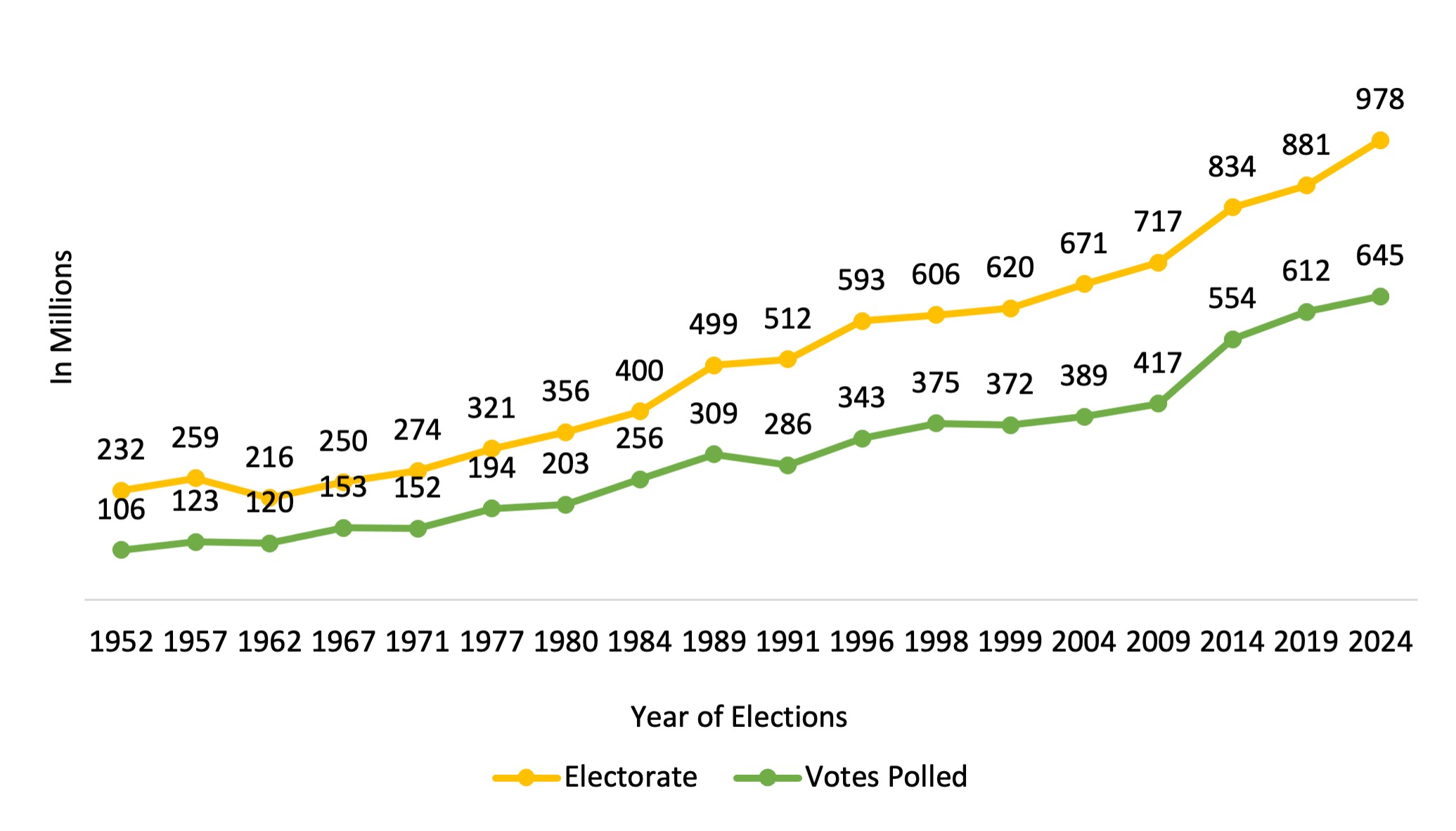

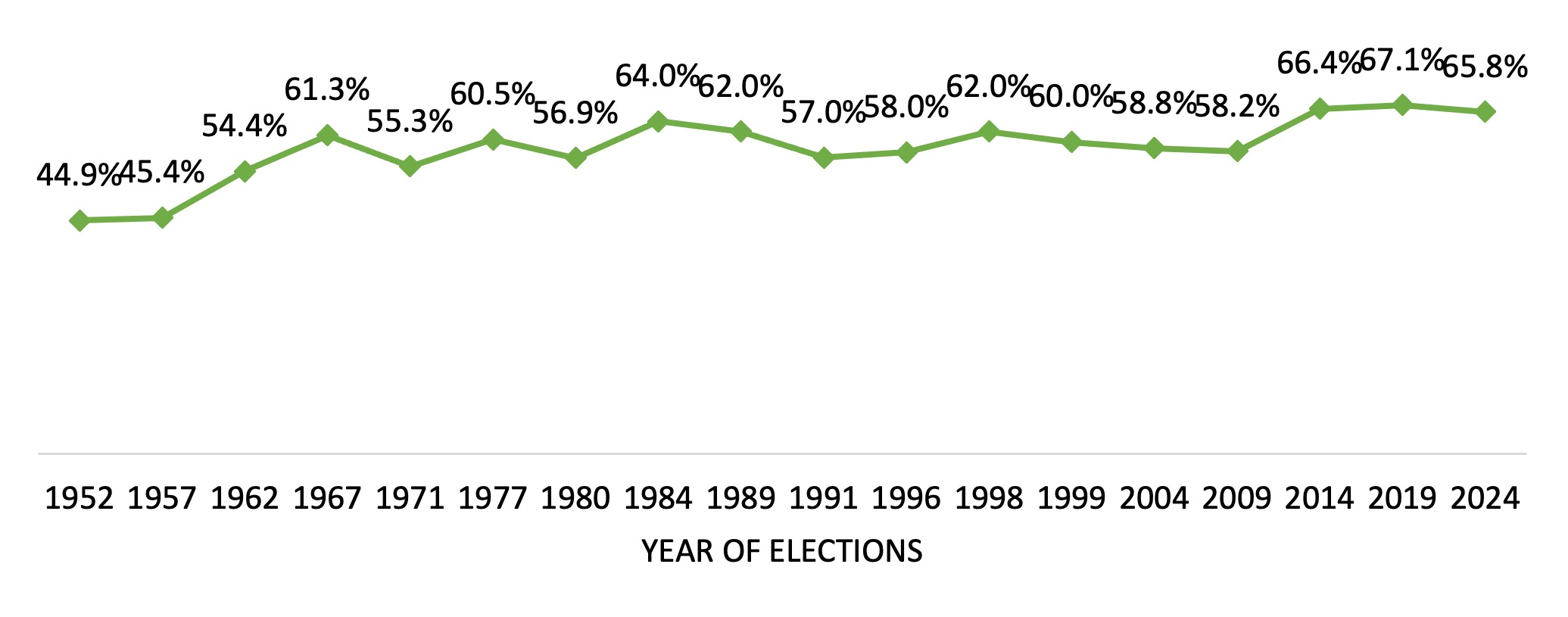

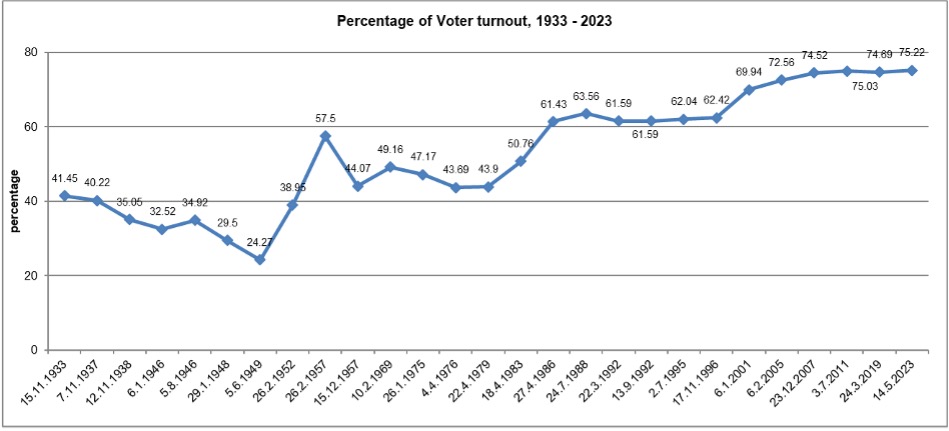

As illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, voter participation has increased substantially over the years. The voter turnout has gone up from 44.9 percent in the first Lok Sabha (parliamentary) elections held in 1952 to 58.2 percent in 2009. The 2014 Lok Sabha election marked a notable shift in electoral participation, observing a turnout of 66 percent, exceeding the previous record of 64 percent set during the 1984 national elections. This election witnessed a turnout that was approximately 8 percent higher than the 2009 Lok Sabha elections, which had a turnout of 58.2 percent. The 2019 Lok Sabha elections registered an even higher turnout, reaching 67.1 percent.

As Kumar (2022) observed, the rise in electoral participation was particularly pronounced in the state assembly elections. The state assembly elections held between 1989 and 2020 exhibited a higher voter turnout not only in comparison to the previous assembly elections but also in comparison to Lok Sabha elections held during the same period. Additionally, Kumar noted that smaller states, including those in the north-eastern part of India, have historically recorded higher voter turnout in both Lok Sabha and state assembly elections (Table 1). His plausible explanation is that the smaller size of the electoral constituency allowed for greater mobilization, as political parties and candidates were able to reach a larger number of voters personally, which in turn encouraged them to come out and cast their votes on election day.

Figure 1. Participation in Lok Sabha Elections (1952 to 2024 Elections)

Source: Election Commission of India and India Votes Portal (https://www.indiavotes.com)

Figure 2. Voter Turnout (percentage) in Lok Sabha Elections (1952 to 2024 Elections)

Source: Election Commission of India and India Votes Portal (https://www.indiavotes.com)

Table 1. Comparison of Average Voter Turnout in Lok Sabha and State Assembly Elections in the North Eastern States

|

North-Eastern States |

Average Turnout |

|

|

Lok Sabha Elections |

State Assembly Elections |

|

|

Arunachal Pradesh |

66.16 |

72.59 |

|

Assam |

73.83 |

77.78 |

|

Manipur |

72.63 |

87.41 |

|

Meghalaya |

62.83 |

81.88 |

|

Mizoram |

62.41 |

80.41 |

|

Nagaland |

80.37 |

79.30 |

|

Sikkim |

77.40 |

79.03 |

|

Tripura |

78.07 |

86.79 |

Source: Kumar 2022

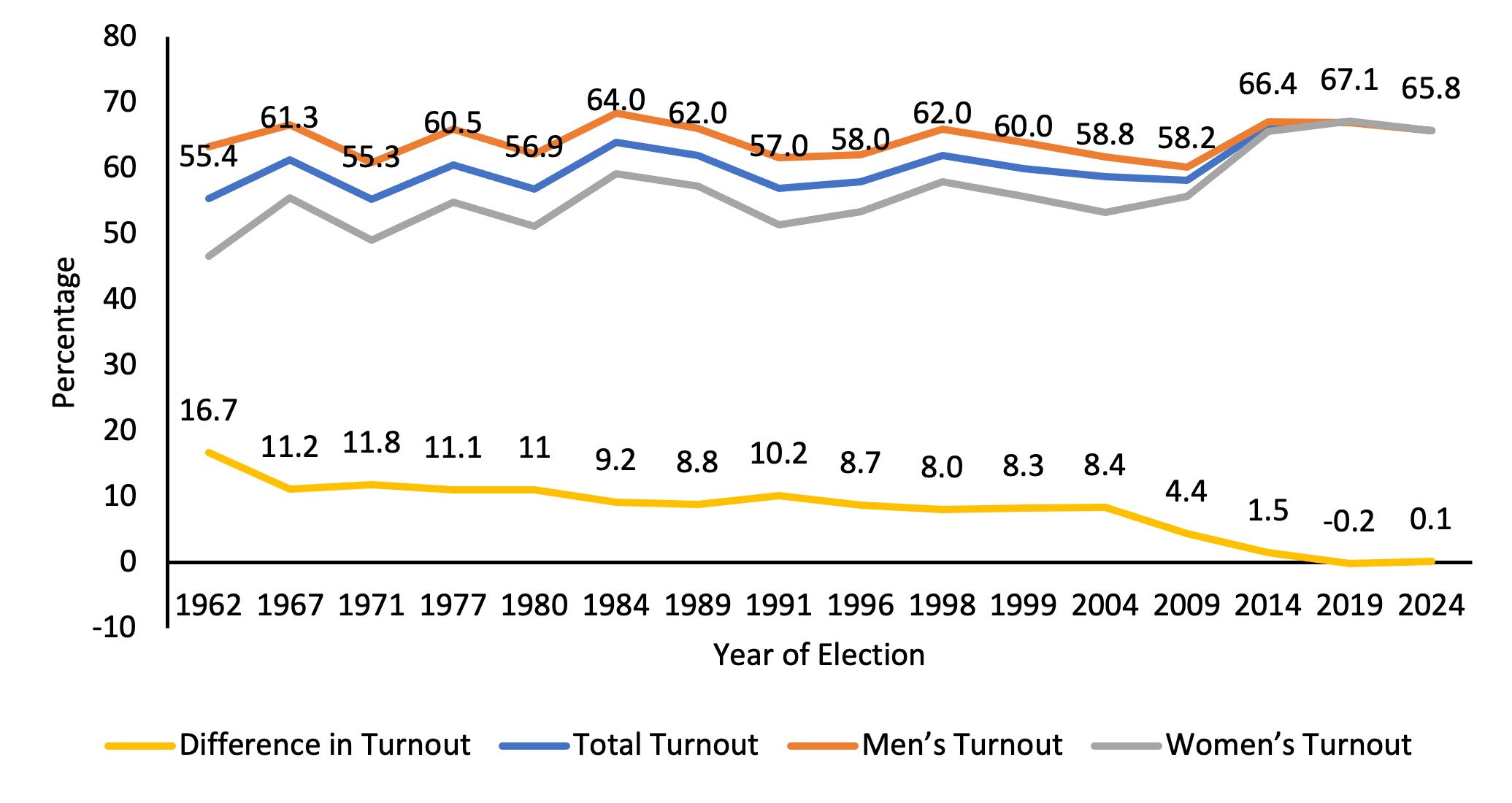

Figure 3. Gender Gaps in Lok Sabha Election Participation (1962 to 2024)

Source: Election Commission of India and India Votes Portal (https://www.indiavotes.com)

The participation of women in elections is an essential indicator of the development of a democratic systеm in any country around the world (Thomas and Wilcox 2005). In India, women of voting age have been eligible to vote since the first general election, with minimal resistance. This was a truly historic achievement, considering that in numerous developed countries, women’s suffrage was only attained through arduous and often violent struggles (Roychowdhury 2024).

This remarkable surge in female voter participation is undoubtedly a cause for celebration. However, it also reveals several paradoxical aspects. Firstly, although female voter turnout in India is increasing, female labor force participation, which is a crucial driver of women’s political engagement, remains lower than that of peer economies (Roscher 2024). Secondly, numerous studies confirm that women remain less engaged in various measures of political involvement than men, including contacting elected representatives, attending public meetings, and participating in campaign activities (Kumar 2024). Despite the increasing number of female voters in India, the representation of women in parliament and state legislatures remains significantly lacking (Deshpande 2004).

Based on these observations, some theorists argue that the electoral processes in India are biased in favor of male dominance, deliberately excluding women from equal power sharing. However, this argument is countered by others who highlight the fact that since the 1990s, there has been a rise in women’s participation in electoral competition and their involvement in grassroots politics, particularly in local governance, suggesting a move towards greater gender inclusivity (Rai 2017). The rise in female participation as candidates in local government elections can be attributed, at least in part, to affirmative action policies that reserve seats for women.

In the last few years, political scholars have accorded several plausible reasons for such an increase in women voters’ participation. Rai (2017) offers five compelling reasons for the upsurge of women’s participation as voters. First, the proliferation of electronic media creates awareness about women’s political and electoral rights. Second, the awareness generation and advocacy efforts at the grassroots level by civil society and women’s groups. Third, the initiatives of the Election Commission of India (ECI) in conducting free, fair, and violence-free elections inculcated a sense of safety and security. Fourth, one-third (fifty percent in some states) reservations for women at the local governance that gave women a sense of sharing power with men equally. Finally, the changing perception of women from seeing politics as dirty and one should stay away from it to participation as an instrument changing power relationship. Individual socio-demographic factors, including education and income, sociocultural norms, and caste, have also been identified as associated with women’s opportunities for political participation (Agarwal 1997; Banerjee 2003; Gleason 2001). Women’s voting patterns in India are also influenced by geographical and spatial factors. Rural women are more likely to vote than their urban and metropolitan counterparts, largely due to the time and financial constraints in reaching polling stations in urban areas (Rai 2011).

The Women’s Reservation Bill 2023, also known as the Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam, was passed in September 2023. This legislation reserves one-third of the seats in the Lok Sabha, state legislative assemblies, and the Delhi Assembly for women, and is being hailed as a transformative development in Indian politics. Despite numerous failed attempts since its initial introduction in Parliament in 1996, the bill’s passage in 2023 is regarded as a historic event. Notably, this reservation is also extended to the seats designated for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) in the Lok Sabha and state legislatures. However, the implementation of this act is contingent upon two determinants. The reservation will become effective upon the publication of the census data collected subsequent to the enactment of the bill. Following the census, the reserved seats for women will be apportioned through a process of delimitation. The reservation is set to last for a period of 15 years, although it may continue until a different date is established by a law passed by Parliament. Additionally, the seats reserved for women will be subject to rotation following each delimitation, as prescribed by parliamentary law (Ghosh 2022; Sahoo and Ghosh 2023).

Two-thirds of India’s population is below the age of 35, contributing to the country’s youthful demographic profile. The younger generation is increasingly regarded as a driving force in social and political change, and their engagement in electoral processes is of significant consequence. In recent decades, young people have been actively participated in various social and political movements, including protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), movements against violence against women (Nirbhaya Movements), anti-corruption movements, and farmers’ movements. Despite this active engagement, there is room for improvement in youth participation in elections, both as registered electorates and voters.

As reported by the Election Commission of India, the electoral rolls for the 2024 Lok Sabha election have been updated to include only slightly over 18 million new voters in the 18- and 19-year-old age bracket. This figure represents a significant shortfall in comparison to the projected population size of this age group, which stands at just under 49 million. In other words, only 38 percent of these first-time voters have successfully registered. Several factors contribute to this situation, including voter apathy, cynicism towards the electoral process, a lack of political representation from their demographic, adm?nistrative challenges, logistical hurdles like paperwork processing, and the opportunity costs associated with voting (The Economic Times 2024-04-05).

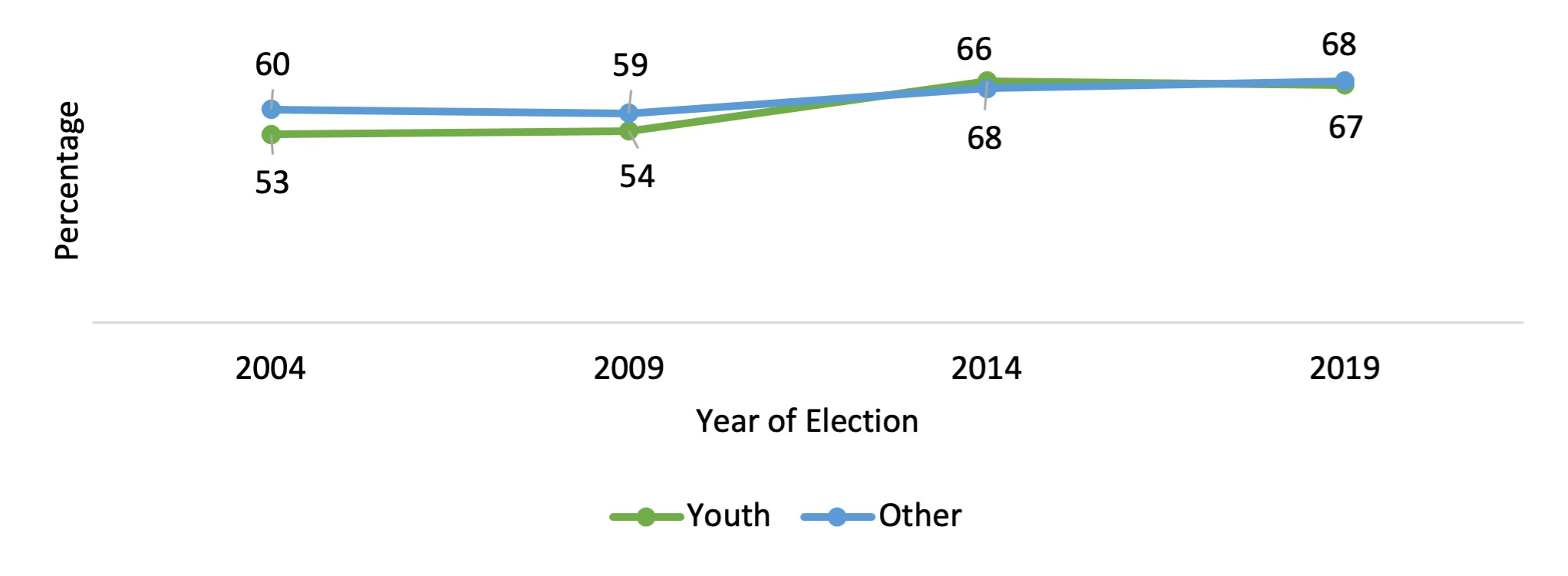

In 2009, the ECI launched the Systеmatic Voter’s Education and Electoral Participation (SVEEP) program with the objective of engaging and educating voters, particularly the youth and women. Figure 3 demonstrates a notable increase in the proportion of young people participating as voters in the 2014 and 2019 elections in comparison to the 2004 and 2009 Lok Sabha elections. This trend has led political parties to recognize the importance of the youth as a key constituency in shaping India’s political landscape and electoral outcomes. According to studies conducted by Lokniti-CSDS, the youth voter turnout increased from 54 percent in 2009 to 68 percent in 2014, surpassing the average voter turnout. However, despite a 9.3 percent growth in the electorate size, the 2019 elections witnessed a stagnation in voter turnout at around 67.4 percent. The ECI identified that the youth, especially those from urban areas, display less interest in participating in the elections.

Figure 4. Voter Turnout among Youth and Others (2004-2019)

Source: Attri and Mishra 2020, based on CSDS Surveys

The data is weighted as per the actual voter turnout.

The political parties and civil society must assume greater responsibility for mobilizing young people in electoral processes. Although the student wings of major political parties have played a significant role in familiarizing youth with politics and fostering political leadership, their integration into political parties requires closer examination. The ambitions of young political leaders often face obstacles when they encounter seasoned veterans within the party. Most parties are unwilling to disrupt the status quo, which leaves these young aspirants feeling increasingly adrift and marginalized. As a result, many choose to leave the party, while others become disillusioned and withdraw from active politics entirely (Hazarika 2024). The problem of youth voter apathy is multi-faceted and requires collaborative and multi-pronged approaches. The National Youth Policy 2014 underscored that there is little coordinated effort along these lines (Gaurishankar and Lal 2023).

Civil society organizations have played a pivotal role in increasing voter turnout, particularly among women and youth. Long before the CEC launched the SVEEP initiative in 2009, organizations such as Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA) had already initiated the Pre-Election Voter Awareness Campaign (PEVAC) to encourage voter enrollment and participation in rural and urban local governance elections across several states (Dasgupta 2010). PEVAC employed a variety of innovative methods, not only to share relevant information about voter registration and voting processes, but also to facilitate interactions between voters and candidates. The Jaago Re campaign by Janaagraha in partnership with Tata Tea, and the #Get Set Vote campaign jointly launched by Youth Ki Awaaz, PRIA, and Facebook in collaboration with the CEC, both played a role in enhancing public awareness, particularly among younger demographics.

3. The Functioning of Election Commission of India

The ECI, with a nearly impeccable history since its formation in 1950, has delivered 18 parliamentary elections (Lok Sabha or Lower House) and several hundred State Assembly elections till date. In 2024, India held its 18th parliamentary election. This election was regarded as the largest electoral exercise in the world, with 978 million registered voters. A total of 18 million individuals between the ages of 18 and 19 participated in the electoral process for the first time. In preparation for this monumental electoral process, the ECI announced the establishment of 1.048 million polling stations and the deployment of 5.5 million EVMs. Additionally, 15 million polling officials and security staff were assigned to facilitate a seamless voting process across seven phases (Mukherjee 2024). The extensive electoral apparatus necessitated meticulous management by the ECI.

The Constitution of India (Articles 324 to 329) provides for the ECI and also stipulates clear guidelines to ensure its autonomy. It has also been vested with residual powers about the electoral process to cope with unexpected problems that might evolve. As rightly described by Kumar (2022), unlike other Indian institutions, the ECI is not a colonial legacy, and it represents all the values and democratic principles that a nascent India aspired for.

Currently, the ECI is a three-member body, with one Chief Election Commissioner (CEC), and two Election Commissioners (ECs). Under Article 324(2) of the Constitution, the President appoints the CEC and ECs. This provision further stipulates that the President, who acts on the aid and advice of the prime minister and the council of ministers, will make the appointments ‘subject to the provisions of any law made in that behalf by Parliament’ (Anand 2022).

The independence of the CEC and ECs is paramount in ensuring free and fair elections. This is obviously contingent upon how independent and transparent are the appointment procedures of the CEC and ECs which have been in political and legal discourses for some time. The current debate was triggered by a Constitution Bench, constituted in 2022 comprising five judges of the Supreme Court. This was in response to a batch of four public interest litigations (submitted in 2015, 2017, 2021, and 2022) which broadly pressed for the issuance of directives to the union government for setting up a neutral and independent selection panel for recommending names to the President for appointments as CEC and ECs. The bench observed that although Article 324(2) of the Constitution makes provision for Parliament to lay out rules and procedures on selecting the CEC and ECs, the absence of such provisions has been exploited by all political parties. This has risen to concerns about the suitability of those appointed, in light of the expectation that they will do the bidding of the dispensation at the relevant time. It further criticized the union governments for failing to provide a full six-year term for the CEC or ECs since 1996. Under the 1991 Election Commission (Conditions of Service of Election Commissioners and Transaction of Business) Act, the CEC and ECs shall hold office for a term of six years or until they reach the age of 65, whichever occurs first.

However, in the absence of a law backed by the parliament, up until December 2023, the CEC and ECs had been appointed by the President on the advice of a committee consisting of the prime minister, the leader of the opposition of the Lok Sabha, and in case no leader of the opposition is available, the leader of the largest opposition party in the Lok Sabha in terms of numerical strength, and the Chief Justice of India.

In December 2023 the parliament passed an Act, replacing the 1991 Act, outlining a procedure for appointing the CEC and ECs. The law, passed by parliament, established a committee comprising the prime minister, the leader of the opposition in the Lok Sabha, and a cabinet minister nominated by the prime minister. The selection will be made from five names shortlisted by a screening panel headed by the law minister and comprising two union secretaries (Chopra 2024).

Since the Supreme Court bench had specified that its appointment norms are “subject to any law to be made by parliament,” the union government was well within its right to bring this law. However, the appointment process proposed in the law raised concerns regarding its potential to undermine the reforms sought by the Supreme Court as well as other civil society groups. The opposition political parties also criticized the committee’s composition because it could effectively sideline the leader of the opposition, who the prime minister and the union minister could consistently outvote.

The ECI is often praised for its management of the massive and intricate election processes using the EVM. However, despite being considered an important Indian innovation, there are doubts about the credibility of the EVM and critics who question its vulnerability. As India approached the 18th parliamentary election, the EVM was once again at the center of political debate. This debate was accentuated further after the state assembly elections in Haryana and Maharashtra on October and November 2024, where several discrepancies in the vote counting were highlighted by the opposition political parties.

The EVM was first used in selected polling stations within Kerala’s Paravur Assembly constituency during a by-election in 1982. However, it faced legal obstacles, resulting in a Supreme Court ruling that it could not be utilized in elections due to the absence of an enabling provision within the law. In response, the government, led by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, a staunch proponent of technological advancement, amended the Representation of the People Act in 1989 to provide legal backing for the use of the EVM. The manufacturing of the EVM was entrusted to two public sector firms: the Electronics Corporation of India Ltd (ECIL) in Hyderabad, and the Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL) in Bengaluru, which also developed prototypes for the EVM.

Since its introduction, the EVM has been met with mistrust, with political parties and observers frequently making claims that it can be hacked or tampered with. Nevertheless, a political consensus was reached by 2004, and the 2004 parliamentary election saw the complete replacement of the traditional ballot box with the EVM. In all 543 parliamentary constituencies, voters cast their votes using the EVM. The counting of votes was completed in less than a day, which was a notable achievement given that the traditional method of counting ballot papers would usually take two to three days.

Over time, the EVM technology has undergone incremental enhancements. The third generation of EVMs comprises three units: a ballot unit, a control unit, and a Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) machine. The control unit and the VVPAT machine are placed in a voting compartment, with the VVPAT machine producing a paper slip as a tangible record of the vote cast. Voters can view the paper slip through a transparent panel on the machine before it falls into a receptacle. The control unit is placed next to the officer-in-charge, thereby guaranteeing that each individual voter is permitted to cast a single vote. Meanwhile, the remaining two units are positioned within the voting compartment, allowing voters to make their choice in a confidential manner. Most former and current CECs have strongly advocated for the use of EVMs. They argue that EVMs are more efficient and reduce malpractices such as rigging and booth capturing, which were prevalent with paper ballots. Many also highlight the issue of invalid votes due to improper marking or ink smudging in paper ballots. Debnath et al. (2017) found that the introduction of EVMs has led to a significant decline in electoral fraud, particularly in politically sensitive states where rigging was common, as well as a decrease in crimes like murder and rape.

In response to a petition by the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), the Supreme Court reaffirmed its trust in the integrity of the electoral process in its judgment in April 2024. The petitioners based their argument on a report published by a news magazine that highlighted inconsistencies in the data recorded by EVMs and VVPATs during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, which the ECI also acknowledged. Subsequently, the Commission clarified that the difference between the EVM and VVPAT counts was due to an inadvertent inclusion of testing votes by the polling officer. The petitioners demanded that all votes cast on EVMs be cross-verified with the accompanying VVPAT paper slips and that paper ballots be reintroduced, although this latter proposal was later withdrawn. At present, only five percent of EVM-VVPAT counts are randomly verified in each assembly constituency. The Court acknowledged the voters’ right to ensure the accuracy of their votes but clarified that this does not entitle them to 100 percent cross-verification of EVM votes with VVPAT slips or physical access to the VVPAT slips (Bhaumik 2024). Although the controversies surrounding the procedure for EVM use were temporarily resolved by the Supreme Court judgment in April 2024, it is highly unlikely that the debate is considered definitively settled for ever, as this debate resurfaced during the recent two state assembly elections in Haryana and Maharashtra.

4. One Nation One Election: Challenges of Simultaneous Election

In India, the first four rounds of general elections in 1952, 1957, 1962, and 1967 for the Lok Sabha and State Legislative Assemblies were held simultaneously. Subsequently, due to the premature dissolutions of the Lok Sabha, State Legislative Assemblies, or both, the elections to the Lok Sabha and State Legislative Assemblies are held at different times. In the two most recent general elections held in 2019 and 2024, only four states (Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Odisha, and Sikkim) out of the 28 states and 8 union territories, along with the Lok Sabha and state legislative assemblies, held. Local government elections (PRIs in rural areas and municipalities in urban areas) are held at varying times. In some states, even elections for PRIs and municipalities are held at different times within the same state.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the current ruling party in India, in its election manifesto in 2014 promised to hold simultaneous elections in Lok Sabha, State Legislative Assemblies, and Local Governments (PRIs and Municipalities). However, it is worth mentioning that the idea of simultaneous elections has been mooted in the past by the ECI in 1982 and the Law Commission in 1999. While a few political parties, part of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) headed by the BJP have argued that holding simultaneous elections at all three levels is the only way to ensure ‘free and fair’ elections, most opposition parties argued against this move for a variety of reasons.

In September 2023, the union government set up a six-member high-level committee (HLC) on ‘one nation, one election’ headed by the former President of India, Mr. Ram Nath Kovind. The committee was mandated to examine and make recommendations for holding simultaneous elections to the Lok Sabha, State Assemblies, municipalities, and panchayats keeping in view the existing constitutional framework. For this purpose, the panel was entrusted with the task of proposing specific amendments to the Constitution and any other legal changes necessary to enable simultaneous elections. The panel also has to give its opinion on whether the proposed amendments shall require the assent of half of the State assemblies, as stipulated in Article 368. The HLC, since then conducted intensive consultations with various stakeholders including the political parties, civil society groups, elected representatives, and Law Commissions, among others.

The arguments in favor of simultaneous elections have clear merits in terms of the burden on public finances and the constraints on governance and development caused by frequent elections. It is estimated that each Lok Sabha election costs approximately 40 billion INR (equivalent to USD 472 million) to the central government alone. The cost of conducting state assembly elections varies from one state to another, depending on the size of the state. Additionally, political parties and individual candidates contribute to the overall expenditure. With simultaneous elections, there would only be one electoral roll, and the government would require the services of security forces and civilian officials only once. This would save public money and human resources that could be allocated to other public needs (Kumar 2023).

The frequency of elections has the effect of prolonging the deployment of security and police forces, which gives rise to concerns about national security and the maintenance of law and order. Furthermore, the adm?nistration becomes strained due to the mass-scale transfers or temporary deployment of officials within and outside the states. The implementation of development projects is also affected due to the enforcement of the model code of conduct. No new projects can be initiated during this period, and even ongoing projects suffer from delays.

Simultaneous elections would reduce the influence of money in elections, as campaign finance for political parties would decrease. The monitoring of election expenditures by the ECI would also become more effective through a coordinated effort at the national level. Additionally, it would help reduce the deleterious effects of regionalism, casteism, and communalism on voter mobilization, as the practice of divisive politics for electoral gain would be less prevalent. Additionally, it would elevate national issues to a more prominent position within the electoral discourse. Finally, it is argued that having too many elections leads to voter fatigue. Voter turnout at the national level has remained stagnant in recent elections (Jain 2024; Nair 2024).

There are strong arguments against implementing simultaneous elections. Firstly, the BJP-led union government’s initiative is seen as hostile to the idea and spirit of constitutional federalism, especially since there was hardly any meaningful consultation with non-BJP-ruled states. Secondly, conducting simultaneous elections may overshadow important local and regional issues in favor of national interests which might lead to regional discontent. Thirdly, proponents of simultaneous elections argue that it would save costs, but this claim is negated by the need to purchase a large number of EVMs and VVPATs. Additionally, there would still be biennial elections to the Rajya Sabha and by-elections, which would require resources and money. Lastly, holding periodic elections ensures that important issues remain in the public domain and keeps political parties and elected representatives accountable.

As the debates continued, the HLC on One Nation, One Election submitted its report to the Indian government in March 2024. Following the formation of the new government in May 2024, the Union Cabinet, presided over by the Prime Minister, accepted the recommendations put forth by the HLC regarding the implementation of concurrent elections for the Lok Sabha, State Legislative Assemblies, and local bodies (Panchayats and Municipalities)

The Committee put forth a framework for holding simultaneous elections, which will require constitutional amendments. In preparation for the next Lok Sabha election, it is recommended that all state assemblies and local bodies be dissolved, irrespective of their remaining terms, as a one-time measure. This will enable the synchronization of all elections. The Committee recommended that elections for the Lok Sabha and all state assemblies be held concurrently, with local body elections occurring within 100 days thereafter. The Committee put forth a number of recommendations in favor of simultaneous elections; however, a few of these have major implications for the electoral process.

Firstly, the current term for a legislature is five years. In the event of a hung legislature, the elections will become asynchronous with regard to the subsequent simultaneous election. To address this issue, the Committee recommended that new elections be held for a hung legislature or local body for a reduced term, equivalent to the remaining period of the five-year cycle for the simultaneous election. This implies that if new elections for a state assembly or the Lok Sabha are held two years after the simultaneous election, their term would be limited to three years. This approach aims to synchronize all elections occurring every five years.

Secondly, the Committee observed that constitutional amendments related to the terms of Parliament and state assemblies will not require ratification by the states. However, constitutional amendments pertaining to local bodies will necessitate the ratification of at least half of the states.

Thirdly, the Committee addressed the issue of using a single electoral roll. Currently, the ECI is responsible for overseeing elections to both houses of Parliament, state legislative assemblies and councils, the president, and the vice president, while the supervision of local body elections is managed by the State Election Commissions (SECs). The preparation of electoral rolls by SECs is subject to the provisions of the respective state legislation. Some state laws allow SECs to prepare separate electoral rolls, whereas others mandate that they utilize the electoral roll prepared by the ECI. The Committee recommended the adoption of a single electoral roll. To implement this single electoral roll, a constitutional amendment will be required. The Committee noted that the proposed amendments would also require ratification by at least half of the states (PRS Legislative Research 2024).

While the pro-government political circles welcomed the Committee’s recommendations, numerous critics have emerged. Many political commentators have criticized the favored arguments presented by the Committee, namely that the proposed scheme would result in cost savings, reduce voter fatigue, improve adm?nistrative convenience, protect social harmony, and stimulate economic development. They have also accused the Committee of failing to explain how the scheme would deepen the government’s accountability to the legislature (Sahu 2024).

Some prominent political opponents even questioned the veracity of the Terms of Reference given to the Committee on the grounds that it asked the Committee to “examine and make recommendations for holding simultaneous elections.” Therefore, the Committee’s implied mandate was to recommend that simultaneous elections were feasible and desirable, without a mandate to recommend against the idea of holding such elections (Chidambaram 2024).

5. Financing of Political Parties and Election Campaigns

The financing of political parties and election campaigns in India has been an unresolved issue for decades. The lack of transparency and inconsistent policies surrounding this matter have had a negative impact on the accountability and transparency of political parties. According to Gowda and Sridharan (2012), flawed political party funding and election expenditure laws are one of the main contributors to corruption in the government and political systеm. These laws encourage parties and politicians to misuse the government’s discretionary powers in order to raise funds for their campaigns and parties. In light of the Indian people’s aspiration for a democratic polity, it is of paramount importance to identify a more effective solution to this problem. Vaishnav (2019) also made a similar observation, stating, “As the costs of elections have increased, politicians – and the bureaucrats under their influence – have become experts at skillfully manipulating regulations and policies in exchange for campaign funds. And if a candidate is fortunate enough to win a higher office, the quest to rebuild their coffers for future elections starts anew.” This section examines four key aspects of financing political parties and election campaigns: expenditure limits, contribution limits, public funding of election campaigns, and reporting and disclosure requirements, all within a historical context.

In India, political parties traditionally obtained funding through private donations and membership fees. Corporate contributions to political parties were allowed; however, there were certain restrictions in place. The Representation of the People Act (RPA), 1951 regulated campaign expenses during elections. Candidates who exceeded the spending limits set by the RPA could face disqualification and have their election results nullified. The Santhanam Committee on Prevention of Corruption (1964), the Wanchoo Direct Taxes Enquiry Committee (1971), the Supreme Court Rule in 1974, the Dinesh Goswami Committee (1990) reports, and the Indrajit Gupta Committee on State Funding of Elections (1998) have drawn attention to the issue of illicit funds infiltrating the political systеm and have proposed measures to improve transparency in the political financing systеm in India.

In 1996, the Supreme Court responded to a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) filed by an NGO called Common Cause, by issuing notices to political parties, requiring them to file returns as mandated by the Income Tax and Wealth Tax Acts. Previously, political parties had been remiss in responding to similar notices issued by the Income Tax Department. The Supreme Court also elucidated that the expenditure incurred by a political party in the context of an election would not be aggregated with that of a candidate in order to ascertain compliance with the expenditure ceiling, provided that the party in question had submitted audited accounts of its income and expenditures.

In 2003, the Election and Other Related Laws (Amendment) Act underwent further revisions. As a consequence of these amendments, political contributions from both companies and individuals became fully deductible for income tax purposes. While this modification was intended to facilitate the solicitation of donations by cheque, it also resulted in the removal of anonymity for donors. Furthermore, the Act mandated that political parties submit a list of donations exceeding INR 20,000 to the Election Commission. In the event of a failure to disclose these donations, the party in question would be subject to the loss of its income tax exemption.

Additionally, the law mandated that political parties and independent supporters report their expenses, which would contribute to the overall expenditure ceiling for a candidate. However, the legislation excluded travel expenses incurred by the top 40 leaders of a recognized national party and the top 20 leaders of a state-level registered party to a candidate’s constituency during an election campaign. These travel expenses would not be included in the candidate’s expenditure. Furthermore, the Act exempted expenditures made by political parties and their supporters for the purpose of promoting the party’s program. Additionally, the expenditure ceiling for a Lok Sabha election was increased to INR 2.5 million, while for state assembly elections, it was set at INR 1 million. In February 2011, the limits were augmented once more, reaching INR 4 million and INR 1.6 million, respectively.

In 2013, the Companies Act of 1956 introduced a new instrument known as the Electoral Trust Scheme. According to the regulations, Electoral Trusts are authorized to receive voluntary contributions from individual Indian citizens, companies registered in India, firms, and Hindu Undivided Families (HUFs). These contributions may be made via cheque, bank draft, or electronic transfer to the trust’s designated bank account. It is important to note that foreign entities, other registered electoral trusts, and individuals who are neither citizens nor residents of India are prohibited from contributing to these trusts. Electoral Trusts are required to maintain comprehensive records of donors and their contributions, funds distributed to political parties, and expenses incurred by the trust. These accounts are required to be audited and submitted to the income tax authority. The trust is also obliged to disclose the list of donors, the political parties to which the funds were distributed, and the disbursed amounts. As of 2024, there were 18 active Electoral Trusts, with the largest one the Prudent Electoral Trust, which has numerous corporate donors. From 2013 to 2023, the Prudent Electoral Trust raised INR 22.57 billion, with 75 percent of the funds donated to the BJP and 7.35 percent to the Congress party (Karthikeyan 2024).

The discourse on political party financing was revived in 2024 when a Constitution bench of five judges, led by the Chief Justice of India, invalidated the ‘Electoral Bond’ scheme implemented by the BJP. The Electoral Bond Scheme was introduced in 2017 through the Finance Bill, allowing Indian citizens or bodies incorporated in India to purchase unlimited quantities of electoral bonds from specified SBI branches. These bonds could then be donated to registered political parties, who could redeem them through their verified accounts.

In the same year, the Indian NGO, Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), filed petitions in the Supreme Court challenging the amendments to the Finance Act. The petitions alleged that the acts were passed as money bills improperly to avoid scrutiny by the Upper House (Rajya Sabha). The petitioners also argued that the Electoral Bond Scheme would encourage opacity in political funding and could result in widespread electoral corruption. However, in 2018, the union government notified the electoral bond scheme.

In 2023, a three-member bench of the Supreme Court referred the petition against the validity of the Electoral Bond scheme to a Constitution bench composed of five judges. On February 15, 2024, the Constitution bench declared the Electoral Bond scheme unconstitutional, stating that anonymous Electoral Bonds violated the Right to Information and Article 19(1)(a). The Supreme Court also directed the SBI to disclose details of Electoral Bond donations to the Election Commission and ordered the Election Commission to publish this information on its website by March 13, 2024. On March 4, the SBI requested an extension until June 30, 2024, to provide information about electoral bonds to the Election Commission of India. On March 7, a petition was submitted to the Supreme Court, requesting contempt charges to be filed against the SBI. The petition alleged that the bank had deliberately and knowingly failed to comply with the court’s order to submit information about contributions to political parties through electoral bonds. The Supreme Court dismissed the SBI’s plea for an extension and inquired about the SBI’s actions over the past 26 days. The Supreme Court ordered the SBI to disclose information about electoral bonds by the close of business on March 12, 2024 (Outlook 2024-03-12).

The disclosure has raised concerns regarding the lack of transparency in political party financing, further obscuring campaign finance. According to the data, a total of INR 127.69 billion was encashed through electoral bonds between April 12, 2019, and January 24, 2024. The ruling BJP received 47.5 percent (INR 60 billion) of these funds, followed by the All India Trinamool Congress (AITMC) with 12.6 percent (INR 16.09 billion), and the Indian National Congress (INC) with 11.1 percent (INR 14.21 billion). While this data suggests potential wrongdoing, the ruling party has categorically denied any such possibilities. A preliminary analysis revealed that several companies that donated bonds to political parties were also facing financial offense charges by investigative authorities of the union government. Many political pundits and opposition parties have raised concerns about possible quid pro quo (Bose 2024).

Upon the introduction of electoral bonds, the government implemented supplementary amendments to the legislative framework governing campaign finance through the incorporation of specific provisions within the Finance Act. Firstly, the cap on corporate donations, which had previously been restricted to 7.5 percent of a firm’s average net profits over the past three years, was removed. Secondly, the obligation for companies to disclose details of their political donations was revoked. In lieu of providing a comprehensive account of political donations in their annual statements of accounts, firms would be required to disclose only an aggregate figure. Thirdly, the government expanded the definition of a “foreign” firm under the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA), thereby enabling a wider range of firms to legally make political donations. This modification permitted any individual, firm, or special interest group to provide an unrestricted monetary contribution to any political party without disclosing the specific amount, except to the government of the day. One significant aspect of this entire episode was the response of independent institutions, including the Reserve Bank of India, the Election Commission of India, and the Parliament. Despite expressing reservations about the electoral bond scheme, these institutions were unable to resist the government’s actions (Vaishnav 2019).

While the Supreme Court’s ruling has temporarily halted the brazen influence of unlimited crony capitalism in political financing, civil society has remained at the forefront of promoting transparency and accountability of political parties. The National Election Watch, a coalition of nearly 1,500 civil society groups spearheaded by the Association of Democratic Reforms, has made significant contributions to the disclosure of contestants’ assets, academic qualifications, and criminal records. However, the influence of money in political campaigns remains unabated. In recent years, civil society groups have brought the issue of surrogate advertising and targeted online campaigns by political actors to the attention of the CEC. These campaigns are designed to influence voter perception and beliefs. In addition, the use of generative AI, including the promotion of deep fakes, by political actors across the spectrum with the intent to influence voter perception and impact electoral outcomes raises urgent concerns.

6. Conclusion

India remains the largest electoral democracy in the world. Notwithstanding concerns raised by various political groups pertaining to the transparency and accountability of electoral processes, voter participation has demonstrated a consistent upward trajectory in recent elections. As India seeks to establish itself as a global leader based on its democratic credibility, it is imperative that it continues to enhance its internal democratic framework. Achieving this objective is contingent upon the maintenance of the integrity of electoral processes. Similarly, ensuring the representation and inclusivity of various sections of society, particularly women and youth, in elections would make the process more inclusive. Political parties have already taken note of the growing participation of women as voters, despite their lower participation in the economy and broader political activities. The election manifestos of the major political parties in the lead-up to the 2019 and 2024 elections included a range of women’s welfare schemes to attract female voters. This has been a persistent phenomenon, even in the context of recent state assembly elections. While some of these schemes reinforce traditional caregiving roles of women, the transformative force of women in society cannot be ignored any longer.

The historic Women’s Reservation Bill, known as the Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam, was enacted in Parliament in 2023. This legislation provides for one-third reservation for women in the Lok Sabha and state assemblies, and it has the potential to be a game changer in this regard. The women’s movements that have been fervently advocating for this reservation over the past four decades now have the opportunity to reinforce gender equality in political participation.

A multitude of youth organizations are actively engaged in efforts to raise awareness and mobilize young people to enhance their political participation. Political parties and civil society must collaborate to deepen these transformative changes in Indian politics. The government should facilitate this process by enacting appropriate legislation and allocating resources for civil society to work towards this vision.

The Supreme Court’s annulment of the electoral bond scheme has also resulted in a policy vacuum in terms of the future of political funding. As the new government has been formed, it would be prudent for Parliament to prioritize extensive consultations among political parties, businesses, and civil society to develop a transparent and accountable mechanism for financing political parties and election campaigns.

Indian politics has consistently exhibited a notable degree of competitiveness and vitality. However, over the past decade, India has witnessed an unprecedented level of polarization among political parties. This polarization is evident across a range of policy areas, including economic and foreign policy, socio-cultural engineering, and attempts to appeal to the diverse population based on religion, caste, ethnicity, languages, and other factors. This has had an impact on the intense competition among political parties, often at the expense of basic decency. In this scenario, the role of the CEC as an independent and impartial institution is crucial in restoring a sense of decency in electoral competition. The recent changes in laws related to the appointment and management of the Election Commission have been perceived by many as an attempt to render the Commission susceptible to the whims and fancies of the ruling dispensation. In this context, the rule of law alone prove inadequate for maintaining the integrity and neutrality of the Election Commission. The rule of law must be complemented by a sense of morality and values based on democratic principles.

There is a growing recognition of the pivotal role that civil society plays in strengthening grassroots democracy. Mobilization of the most marginalized communities through awareness building and conscientization has greatly enhanced their participation in political processes and the upholding of rights and entitlements. Three significant roles that civil society has been playing – enhancing voter participation through civic education, amplifying citizens’ voices through mobilization, and advocating for greater transparency and accountability in the electoral systеm through public advocacy – need to be supported and strengthened. ■

References

Agarwal, Bina. 1997. “Editorial: Re-sounding the Alert – Gender, Resources and Community Action”, World Development 25(9): 1373-1380.

Anand, Utkarsh. 2022. “Independence of Election Commission destroyed by all govts, says Supreme Court.” Hindustan Times. November 23. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/independence-of-ec-destroyed-by-all-govts-says-sc-101669139785719.html (Accessed May 3, 2024)

Attri, Vibha, and Jyoti Mishra. 2020. “The Youth Vote in Lok Sabha Elections 20191.” Indian Politics & Policy 3, 1: 87-107. https://www.ippjournal.org/uploads/1/3/6/5/136597491/the_youth_vote_in_lok_sabha_elections_2019.pdf (Accessed May 18, 2024)

Banerjee, Sikata. 2003. “Gender and Nationalism: The Masculinization of Hinduism and Female Political Participation in India.” Women’s Studies International Forum 26, 2: 167-179.

Bhaumik, Aaratrika. 2024. “EVM-VVPAT case: What are the key takeaways from the Supreme Court’s verdict?” The Hindu. April 27 (Updated May 9, 2024). https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/evm-vvpat-case-key-takeaways-from-supreme-court-verdict/article68109342.ece (Accessed May 10, 2024)

Bose, Prasenjit. 2024. “Decoding electoral bonds data.” The Hindu. March 19. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/decoding-electoral-bonds-data/article67969866.ece (Accessed May 1, 2024)

Chidambaram, P. 2024. “Kovind committee report: dead on arrival.” The Indian Express. September 22. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/p-chidambaram-writes-kovind-committee-report-dead-on-arrival-9581116/ (Accessed December 1, 2024)

Chopra, Ritika. 2024. “Explained: The new process for picking Election Commissioners, why it was brought in.” The Indian Express. February 9. https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/picking-election-commissioners-9149779/ (Accessed March 15, 2024)

Dasgupta, S. 2010. Citizen Initiatives and Democratic Engagement: Experiences from India. New Delhi: Routledge.

Debnath, Sisir, Mudit Kapoor, and Shamika Ravi. 2017. “The Impact of Electronic Voting Machines on Electoral Frauds, Democracy, and Development.” Brookings Institution. March 16. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/evm_march2017.pdf (Accessed April 18, 2024)

Deshpande, Rajeshwari. 2004. “How Gendered was Women’s Participation Women in Election 2004?” Economic and Political Weekly 39, 51: 5431-5436.

Election Commission of India. n.d. Election Results – Full Statistical Report. https://www.eci.gov.in/statistical-reports (Accessed December 1, 2024)

Gaurishankar, S., and Harsha Lal. 2023. “Do Young Indians Participate in Elections?” Centre for Public Policy Research (CPPR). November 1. https://www.cppr.in/articles/ylf-youth-vote (Accessed May 18, 2024)

Ghosh, A. K. 2022. “Women’s Representation in India’s Parliament: Measuring Progress, Analysing Obstacles.” Occasional Paper, Issue No. 382, November 2022. Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/public/uploads/posts/pdf/20230717151038.pdf (Accessed May 18, 2024)

Gleason, Suzanne. 2001. “Female Political Participation and Health in India.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 573: 105-126.

Gowda, M. V. Rajeev, and E. Sridharan. 2012. “Reforming India’s Party Financing and Election Expenditure Laws.” Election Law Journal 11, 2: 226-240. https://casi.sas.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/upiasi/Reforming%20India%27s%20Party%20Financing%20and%20Election%20Expenditure%20Laws.pdf (Accessed April 10, 2024)

Hazarika, Thajeb Ali. 2024. “Why Indian youth is not at the polls: Political parties need to do more.” The Indian Express. May 10. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/why-indian-youth-is-not-at-the-polls-political-parties-need-to-do-more-9319104/ (Accessed May 18, 2024)

Jain, J. 2024. “Simultaneous elections can strengthen democracy.” The Indian Express. September 26. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/simultaneous-elections-can-strengthen-democracy-9588264/ (Accessed December 1, 2024)

Karthikeyan, Suchitra. 2024. “Electoral bonds vs Electoral Trusts: What are they and how do they differ?” The Hindu. April 15. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/electoral-bonds-vs-electoral-trusts-what-are-they-and-how-do-they-differ/article67975344.ece (Accessed May 1, 2024)

Kumar, Ashutosh. 2023. “Understanding simultaneous elections.” The Hindu. November 30 (Updated April 10, 2024). https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/understanding-simultaneous-elections-explained/article67592051.ece (Accessed April 15, 2024)

Kumar, Rithika. 2024. “What Lies Behind India’s Rising Female Voter Turnout.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. April 5. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/04/what-lies-behind-indias-rising-female-voter-turnout?lang=en (Accessed May 17, 2024)

Kumar, Sanjay. 2022. Elections in India: An Overview. New York: Routledge.

Mishra, Soni. 2024. “Are EVMs credible? Here’s what ECI and former commissioners told THE WEEK.” The Week. April 7. https://www.theweek.in/theweek/current/2024/03/30/electronic-voting-machine-history-costs-credibility.html (Accessed April 18, 2024)

Mukherjee, Vasudha. 2024. “General Election 2024: Here’s what it will take to elect 18th Lok Sabha.” Business Standard. March 16. https://www.business-standard.com/elections/lok-sabha-election/general-election-2024-here-s-what-it-will-take-to-elect-18th-lok-sabha-124031600364_1.html (Accessed May 3, 2024)

Nair, A. 2024. “One nation, one election: A promise of stability.” Hindustan Times. October 12. https://www.hindustantimes.com/ht-insight/governance/one-nation-one-election-a-promise-of-stability-101728728379883.html (Accessed December 1, 2024)

Outlook. 2024. “Electoral Bonds Scheme Timeline: The Journey From Its Inception To Supreme Court Holding It Unconstitutional.” March 12. https://www.outlookindia.com/national/electoral-bonds-scheme-timeline-the-journey-from-its-inception-to-supreme-court-holding-it-unconstitutional (Accessed May 11, 2024)

PRS Legislative Research. 2024. “High Level Committee Report Summary – Simultaneous Elections in India.” https://prsindia.org/policy/report-summaries/simultaneous-elections-in-india (Accessed December 1, 2024)

Rai, Praveen. 2011. “Electoral Participation of Women in India: Key Determinants and Barriers.” Economic and Political Weekly 46, 3: 47-55.

______. 2017. “Women’s participation in electoral politics in India: Silent feminization.” South Asia Research 37, 1: 58-77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0262728016675529 (Accessed December 1, 2024)

Roscher, Franziska. 2024. “How Clientelist Party Mobilization Closes the Gender Turnout Gap: Theory and Evidence from India.” January 8. https://franziskaroscher.com/research.html (Accessed May 17, 2024)

Roychowdhury, Adrija. 2024. “From 1951-2019: How women voters outnumbered men in Lok Sabha polls.” The Indian Express. May 7. https://indianexpress.com/article/research/from-1951-to-2019-how-women-voters-outnumbered-men-9306969/ (Accessed May 16, 2024)

Sahoo, N. and Ghosh, A. K. 2023. “India’s Women Quota Law is a Game Changer for Gender Inclusive Politics.” ADRN Issue Briefing. November 17. http://www.adrnresearch.org/publications/list.php?at=view&idx=342 (Accessed December 1, 2024)

Sahu, S. N. 2024. “How Kovind Committee Report on Simultaneous Elections Ignores Ambedkar’s Vision of Parliamentary Democracy.” The Wire. September 25. https://thewire.in/government/how-kovind-committee-report-on-simultaneous-elections-ignores-ambedkars-vision-of-parliamentary-democracy (Accessed December 1, 2024)

The Economic Times. 2024. “Why young voters are less interested in elections?” April 5. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/elections/lok-sabha/india/why-young-voters-are-less-interested-in-elections/articleshow/109066465.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest (Accessed May 18, 2024)

Thomas, Sue, and Clyde Wilcox, Eds. 2005. Women and Elective Office: Past, Present and Future. New York: Oxford University Press.

Vaishnav, Milan. 2019. “Electoral Bonds: The Safeguards of Indian Democracy Are Crumbling.” HuffPost India. November 25. Republished in Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2019/11/electoral-bonds-the-safeguards-of-indian-democracy-are-crumbling?lang=en (Accessed May 1, 2024)

[1] Director, Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA), India

[2] Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana, Maharashtra, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh.

[3] Nominated by the Governor, elected by the graduates and teachers.

[4] The tree-tier PRIs include Gram Panchayat at the village or village-cluster level, Block Panchayat at the Block level and Zill Parishad at the district level. Each voter casts three votes to elect members at these three levels.

[5] There are three categories of Municipalities – Municipal Corporations for the larger cities, Municipal Councils for the medium-sized towns and Nagar Panchayats for small or transition towns.

Vertical Accountability in the Case of Indonesia

Devi Darmawan[1], Sri Nuryanti[2]

Indonesian Research and Innovation Agency

1. Introduction

Citizens in all regime types can exercise government accountability (Lindberg 2013). However, the possibility of acquiring government accountability is more likely to happen in democratic countries. Government accountability is understood as a constraint on the government’s use of political power through requirements for justification for its actions and potential sanctions. Conceptually, there are three types of accountability based on the actors who run the constraints to check and balance the government: vertical accountability, horizontal accountability, and diagonal accountability. In this context, vertical accountability refers to the ability of a state’s population to hold its government accountable through elections; horizontal accountability refers to checks and balances between institutions; and diagonal accountability captures oversight by civil society organizations (CSOs) and media activity. Consequently, the three would generate a distinct type of accountability deficit.

In democratic regimes, O’Donnell claimed that vertical accountability is not enough to stop such encroaching authoritarianism. However, I argued that vertical accountability played a significant role in halting democracy from backsliding, especially when the government has captured the cabinet and all the government institutions, including parliament and the judiciary, since forms of vertical accountability, including elections and political parties, can help remove incumbents who abuse their powers from office. This argument is also supported by Anderson (2006), who found evidence in Nicaragua that the mechanisms of vertical accountability have proven more effective than expected in restraining executive authoritarianism and fostering institutions of horizontal accountability. The case of Nicaragua shows that citizens can use the power balance and separate institutional mandate of presidential democracy to limit authoritarianism. However, there is a limited study on the vertical accountability mechanism and its effectiveness in the growing literature of democratic study in Indonesia, especially to find out whether the vertical accountability mechanism works effectively to constrain executive aggrandizement and prevent encroachment authoritarianism in Indonesia.

Vertical accountability is an essential component of democratic governance, and it plays a vital role in ensuring that elected representatives remain responsive to the wishes and needs of their constituents in Indonesia and other democratic nations. Based on this background, this study will cover the main analytic focal points, including the quality of elections and political parties. Therefore, this study coverage aims to identify the gaps between the institutional mechanisms of vertical accountability and the actual performance over time in the case of Indonesian democracy, specifically to analyze the quality of elections and the political parties in politics.

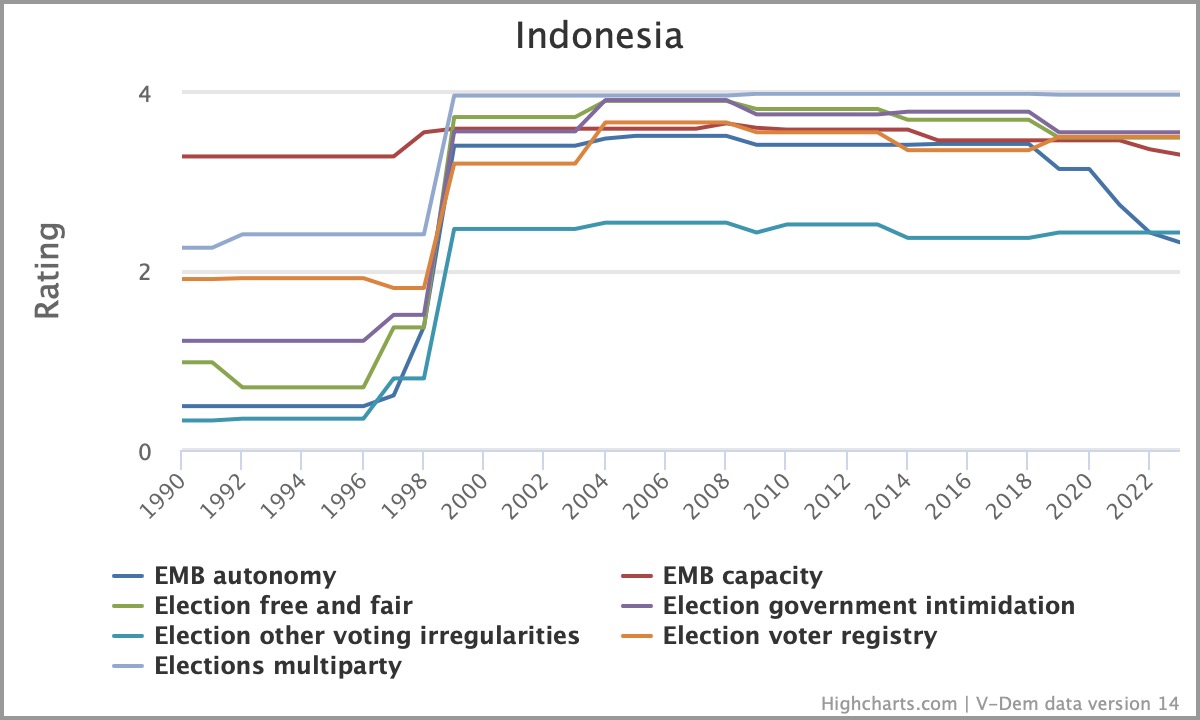

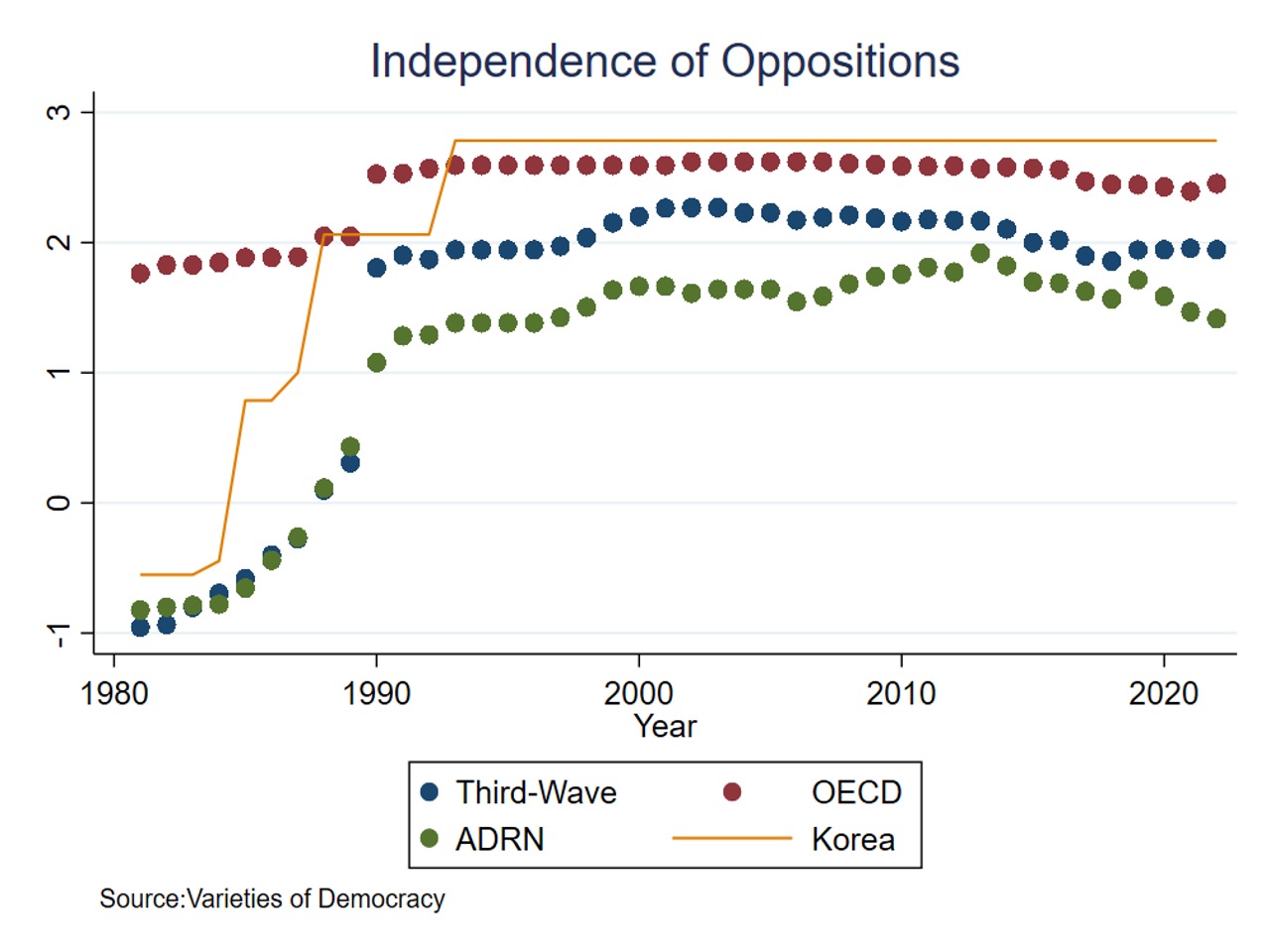

2. Measuring Vertical Accountability in Indonesia

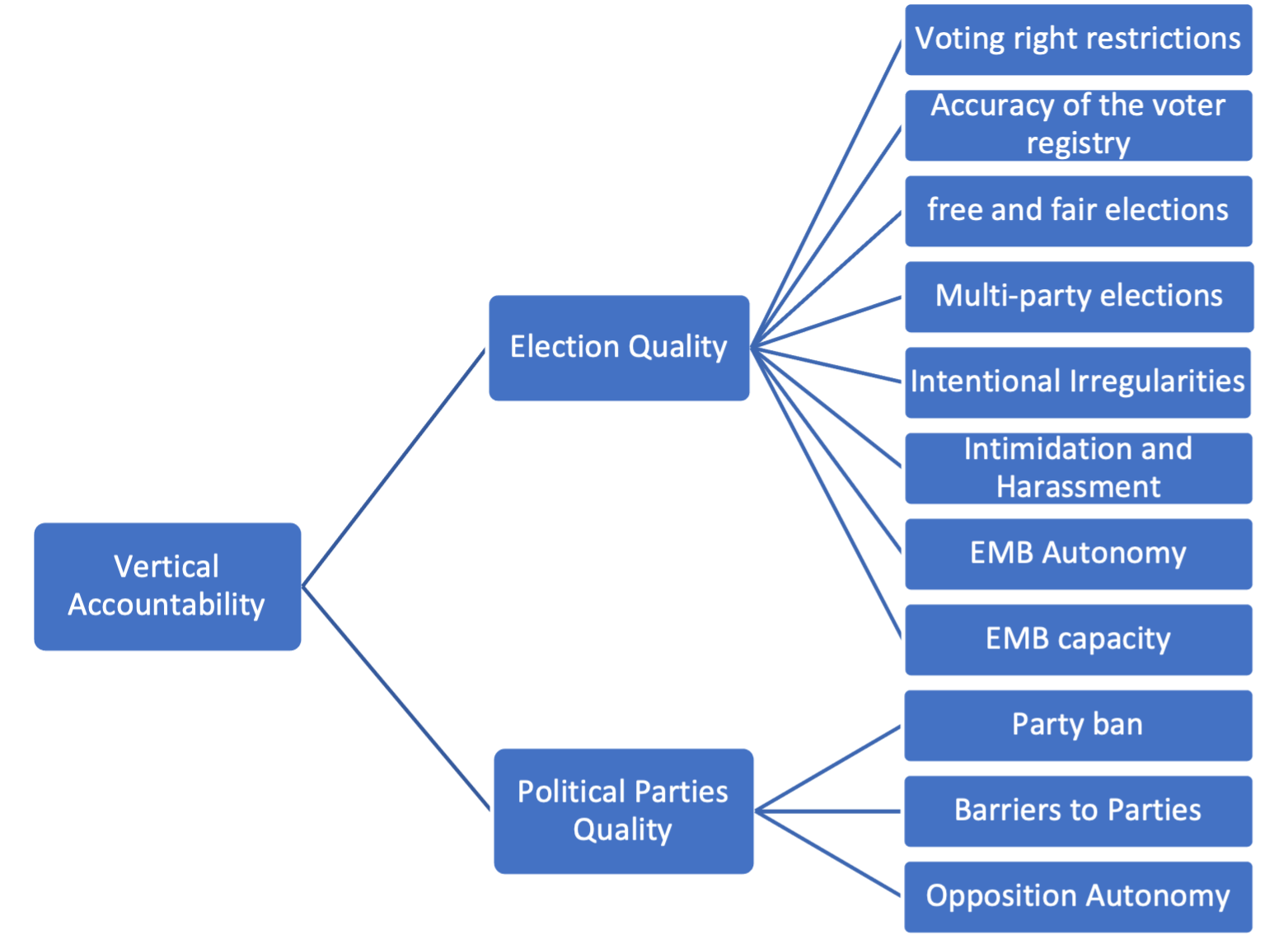

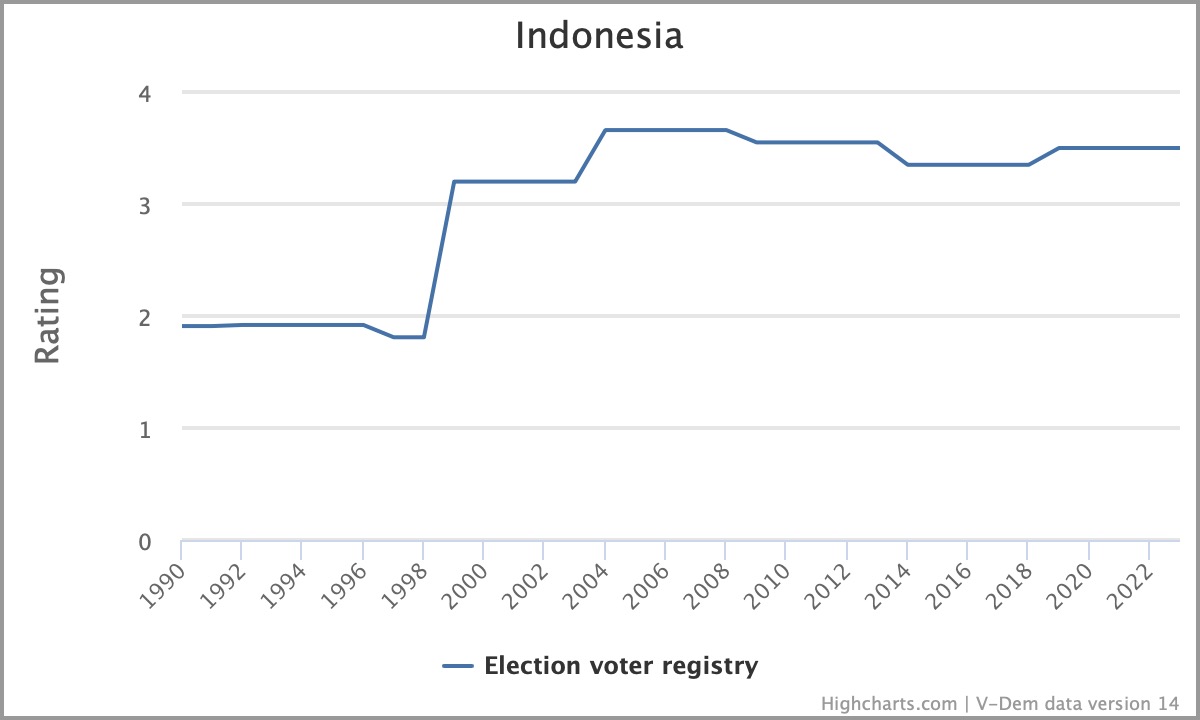

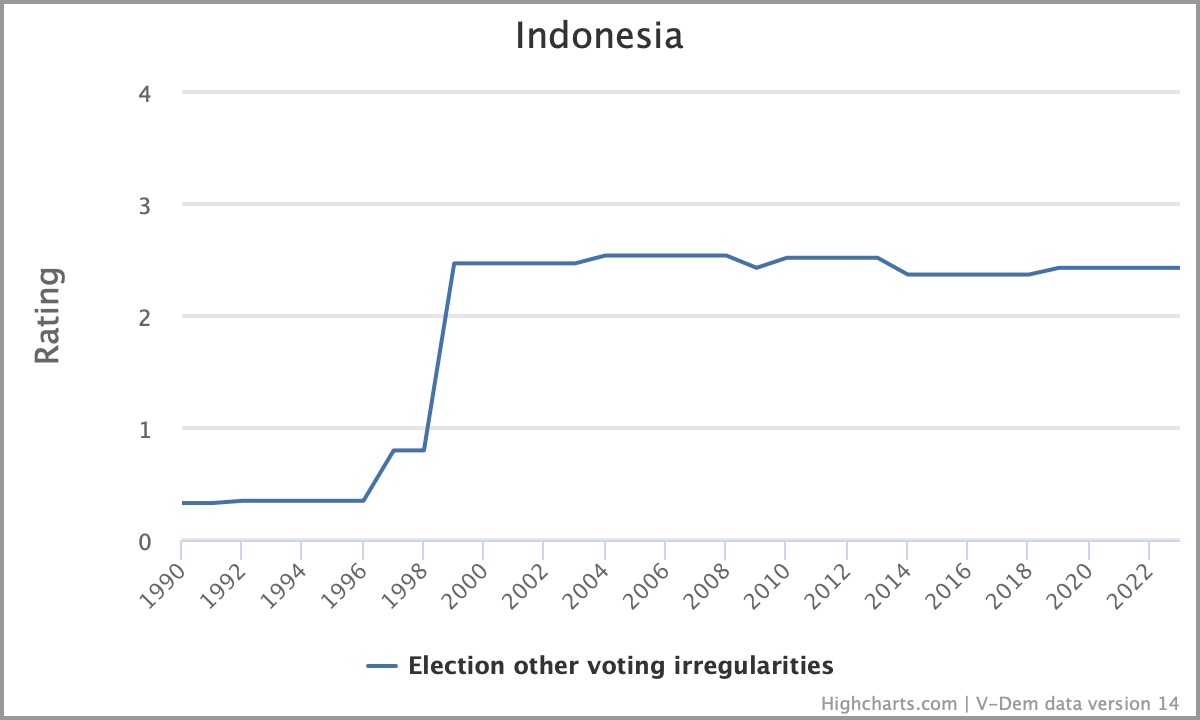

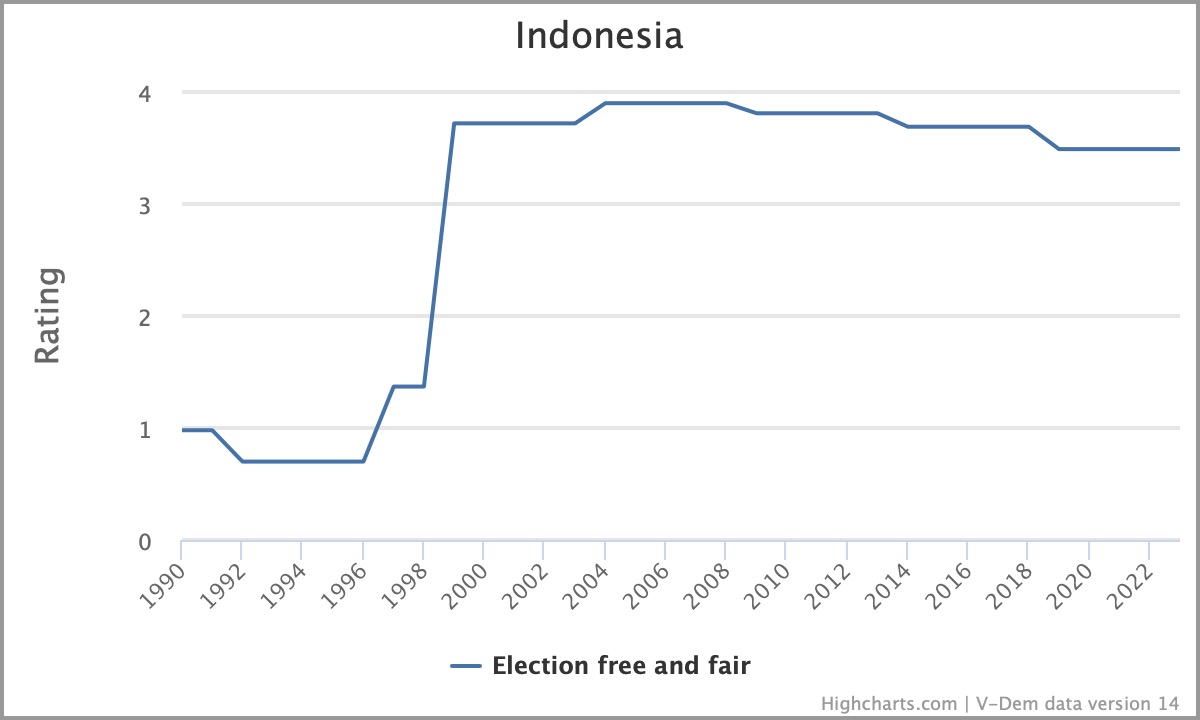

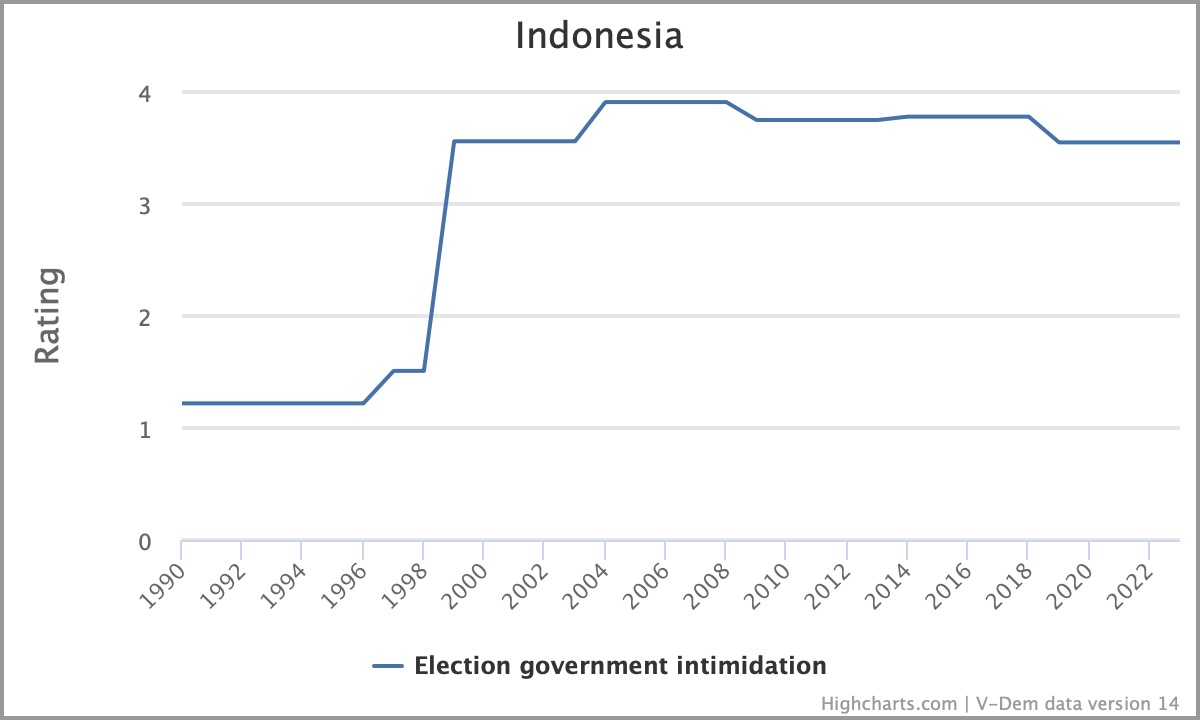

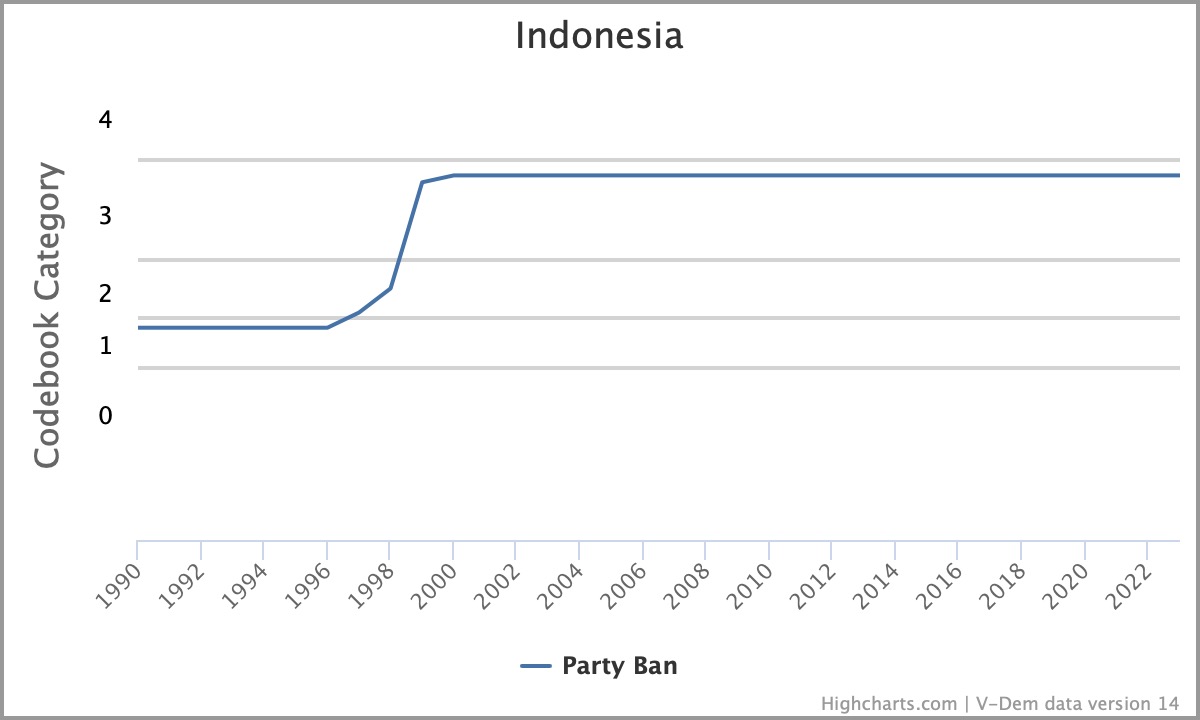

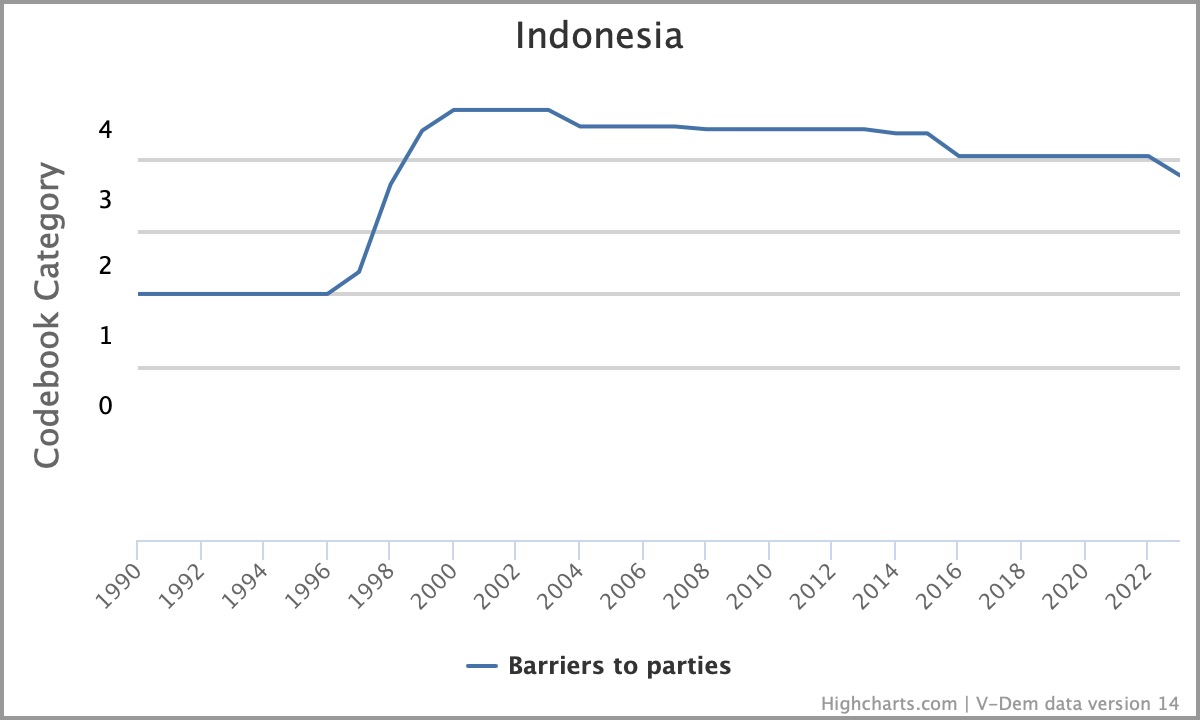

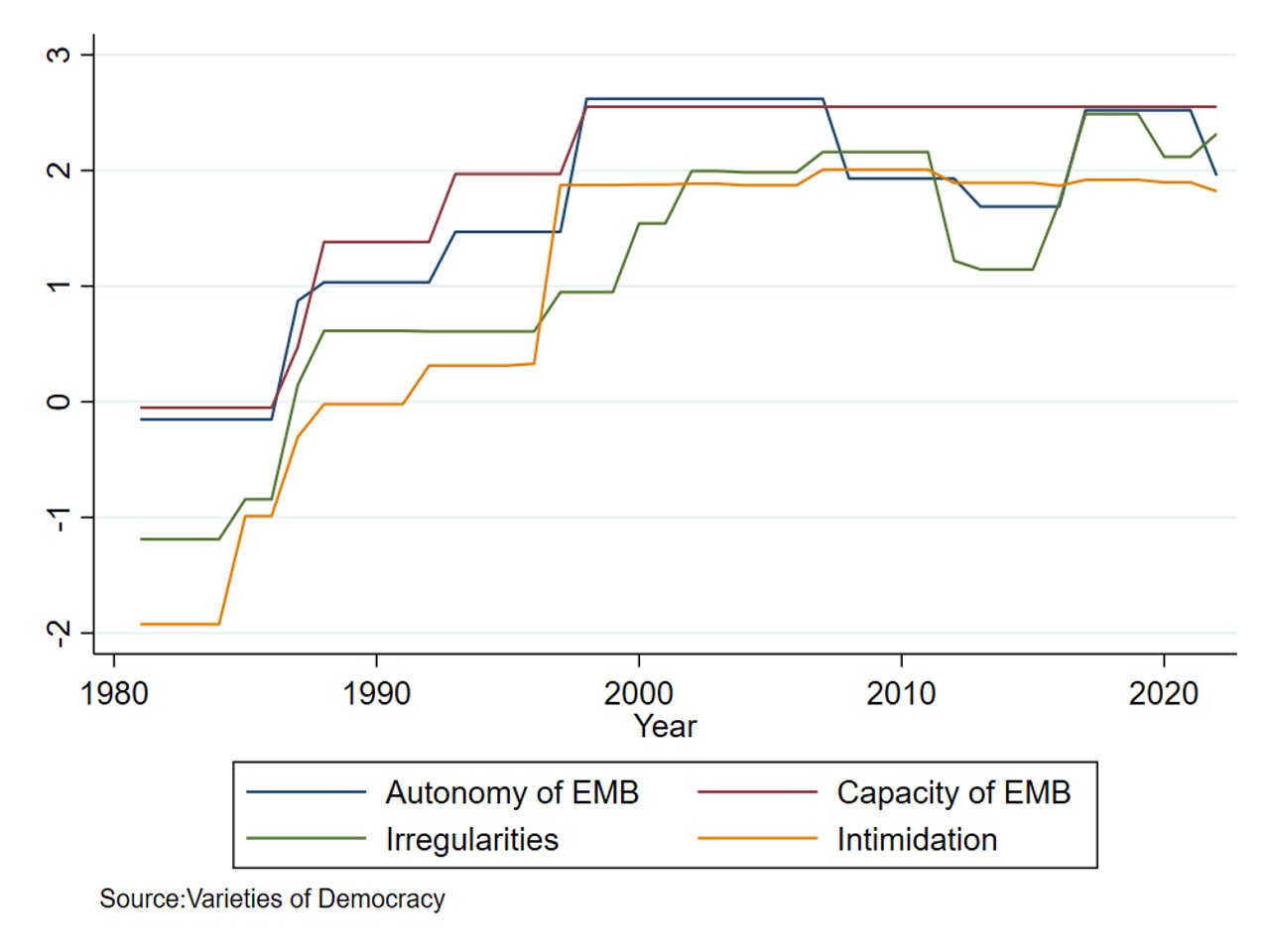

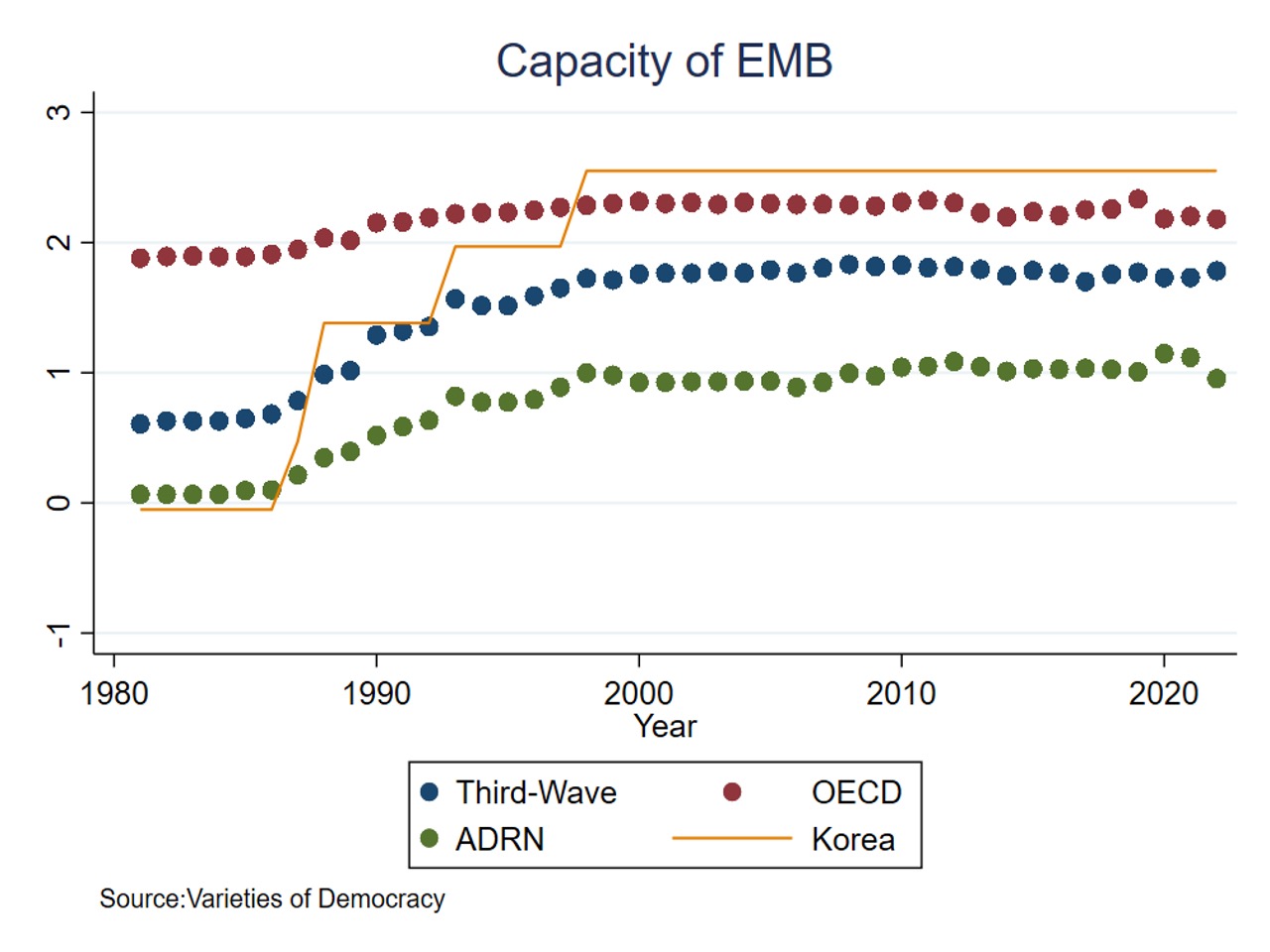

Theoretically, vertical accountability occurs when citizens have the power to hold the government accountable. Vertical accountability mechanisms include formal political participation on the part of the citizens — such as being able to freely organize political parties — and participate in free and fair elections, including for the chief executive. Eventually, the proper assessment of vertical accountability should be based on electoral accountability that proxies the quality of elections and the condition of political parties in competing elections. In measuring the quality of elections, the variables should consist of several factors, including autonomy and capacity of the electoral management body, accuracy of the voter registry, intentional irregularities conducted by the government and opposition, intimidation, and harassment by the government and its agents, to what extent the elections were multi-party in practice, and an overall measure for the freedom and fairness of elections.

In addition, to measure to what extent the political parties support the vertical accountability mechanism, the analysis should focus on whether there are barriers to forming a party, how restrictive they are, and the degree to which opposition parties are independent of the ruling regime. Both measurements of the quality of elections and political parties are the best estimations of how vertical accountability is established in democratic countries to portray the state’s population to hold its government accountable through elections. Therefore, vertical accountability operationalizations would constrain the government and prevent autocratization episodes from taking place in a democratic country. Hypothetically, if these institutions (elections and political parties) work, they will ensure vertical accountability and prevent democracy from declining. In contrast, if these institutions erode, democratic regimes will experience a democratic decline. This paper attempts to identify whether the election and political party’s quality could work to generate a vertical accountability mechanism to prevent further democratic decline.

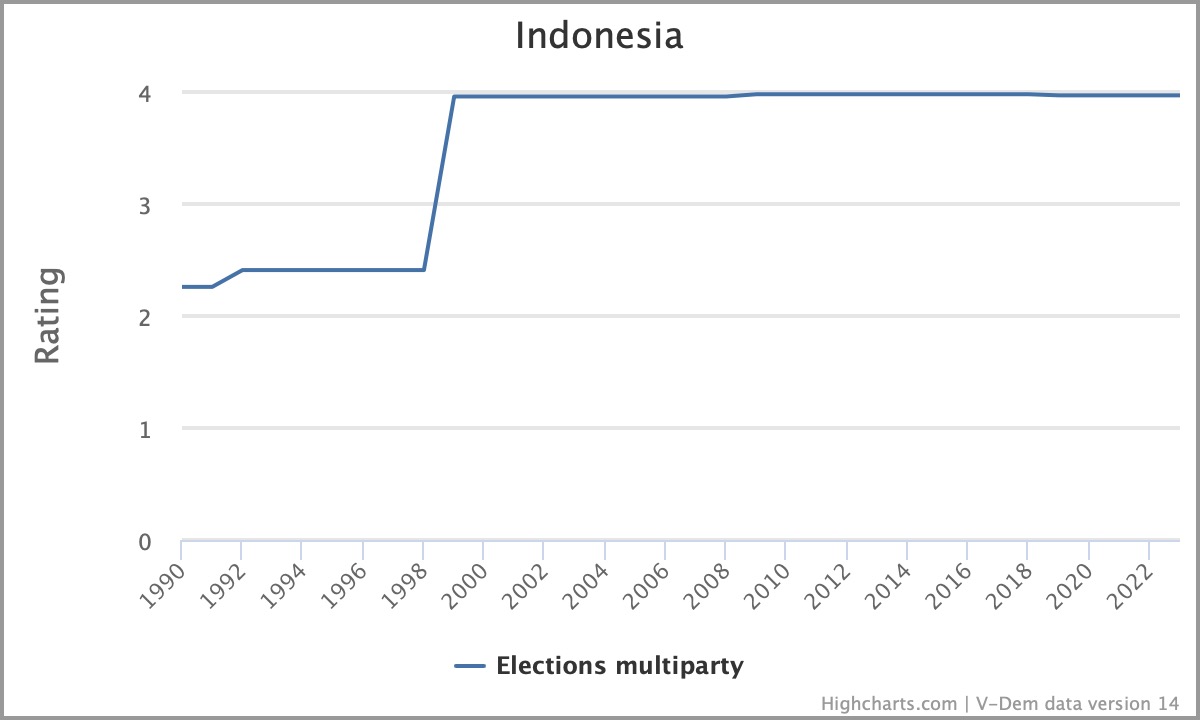

Figure 1. Contributing Variables to Vertical Accountability

As in many democratic countries, Indonesia has conducted elections since 1955. Up until the 1999 election, only legislative elections had the direct election systеm, while the president and vice president appointed by People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR). The systеm was improved by the successful reformation conducted by activists, scholars, and students in 1998, followed by the establishment of the direct election systеm for executives and legislative members. In the post-reformation, the government has consistently held regular elections both at the local and national levels once every five years. Indonesia has conducted the national election approximately six times since 1998, in 1999, 2004, 2009, 2014, 2019, and 2024.

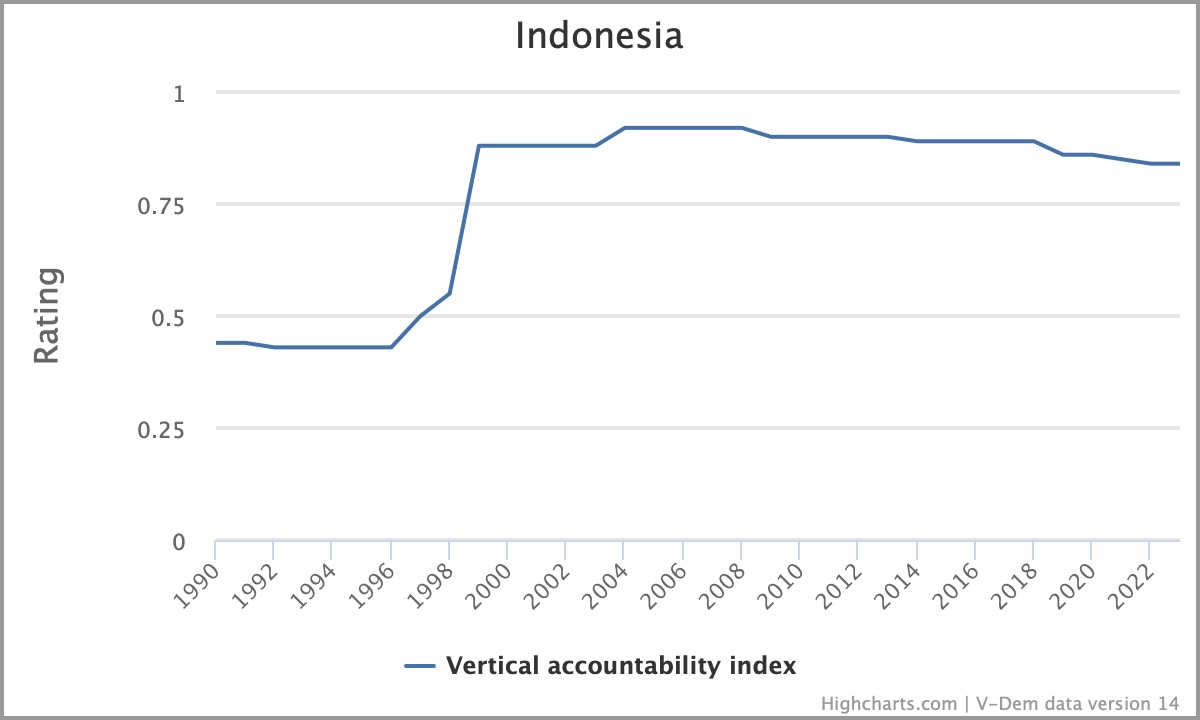

Ideally, the more experienced Indonesia is in holding regular elections, the more powerful its citizens are in acquiring government accountability. However, after a significant lapse in the post-1999 era, the vertical accountability score in Indonesia has failed to improve. Based on V-Dem data on the vertical accountability index in Indonesia, on a scale of 0-1, Indonesia achieved a score of 0.85, which means its citizens have the power to hold the government accountable through elections or other channels of political participation. However, it has slightly decreased since 2018, showing no improvement in pulsing vertical accountability to the maximum level, as depicted by the figure below.

Figure 2. Index of Vertical Accountability in Indonesia

Based on V-Dem Data, the vertical accountability index for Indonesia has steadily decreased since 2008. This data contrasts the fact that Indonesia has been implementing elections from 2004 until 2024. Taking this into account, Indonesia’s experience in holding quite a lot of elections should elevate the accountability index. Unfortunately, the data shows the other path leans in a slightly decreasing direction.

3. Election’s Quality in Indonesia

Vertical accountability has its roots in the relationship between the elected government and the citizens as voters. Thus, the vertical accountability mechanism allows people to hold their elected executives at the national level, such as the president and vice president, and executives at the local level, such as governors, regents, or mayors, accountable. To those elected, citizens, as the ‘vertical’ element, have the means to express their expectations, concerns, and evaluations toward the executives through the elections.

Indonesia conducts elections regularly once every five years (periodic elections) to choose the president and vice president, the Regional Representative Council (DPD) and the People’s Representative Council (DPR), and executives at the local level, such as governors, mayors, and regents. Since the reformation took place, Indonesia managed to hold approximately five multiparty elections at the national level to choose the president and vice president, and members of parliament directly in 2004, 2009, 2014, 2019, and the recent election in 2024. The experience of holding elections regularly every five years in Indonesia to elect the executive and legislative branches has successfully built up a global perspective that Indonesia has become more and more democratic. As such, the experience of holding regular elections can be seen as a form of implementing vertical accountability in Indonesia during the last two decades after Soeharto was no longer in power.

Before the reformation era in 1999, elections in Indonesia had been under autocratic regimes. Even though Indonesia successfully held national elections in 1971, 1977, 1987, 1992, and 1998, those elections resulted President Suharto as the winner from election to election. Thus, he had maintained his power through the elections as head of state and head of executives. The domination of the president’s political party, both in bureaucracy and at the grassroots level, exacerbated the condition. In other words, the failure of New Order democracy was caused by the almost non-existent rotation of executive power, closed political recruitment, and elections that did not adhere to the spirit of democracy, which meant the ability of elections to act as an effective means to hold the government accountable was almost nil.

After Suharto was overthrown, a new phase of democratization began. The new president, B.J. Habibie, changed the constitution and electoral systеm to ensure the quality of elections met the international standard of electoral integrity. Moreover, post-1998 reforms led to the reintroduction of multipartyism and laying down foundations for a more effective means of vertical accountability by government and other persons holding elected positions to the electorate. The regular holding of multiparty elections became the norm at the national level and followed at the local level, along with the implementation of decentralization in 2005. The real question is whether the elections provide citizens with genuine opportunities, inter alia, to hold Indonesian governments accountable, dependent on the quality of these elections and whether they provide citizens the freedom and ability to make free choices on whom to elect. Eventually, a thorough analysis must be conducted to determine whether the quality of the election can support the creation of vertical accountability in Indonesian democracy. In the last election held in 2024, the quality of the election was at stake due to the Constitutional Court’s decision that paved the way for the current president’s son to become a vice-presidential candidate in the 2024 general election.

Several factors determine election quality, including the restriction on voting rights, autonomy and capacity of the electoral management body (EMB), the accuracy of the voter registry, intentional irregularities conducted by the government and opposition, intimidation, and harassment by the government and its agents, to what extent the elections were multi-party in practice, and an overall measure for the freedom and fairness of elections.

3.1. No Voting Right Restrictions

Indonesia guarantees the right to vote for all Indonesian citizens as part of respect for human rights, as stated in Indonesia’s Constitution and the Law on Human Rights. Article 1 Paragraph (2), Article 6A (1), Article 19 Paragraph (1), and Article 22C (1) of the 1945 Constitution regulate the right to vote, while in Law No. 39 of 1999 on Human Rights, the guarantee of the right to vote is regulated by Article 43 paragraphs 1 and 2 which states that every citizen has the right to participate in government directly or through a freely chosen representative, in a manner determined by statutory regulations. These provisions indicate the existence of a legal guarantee inherent in every Indonesian citizen to be able to exercise their right to vote. The General Elections Commission (KPU) Regulation then regulates the requirements for voters, namely Indonesian citizens who are 17 (seventeen) years of age or older, married, or have been married.

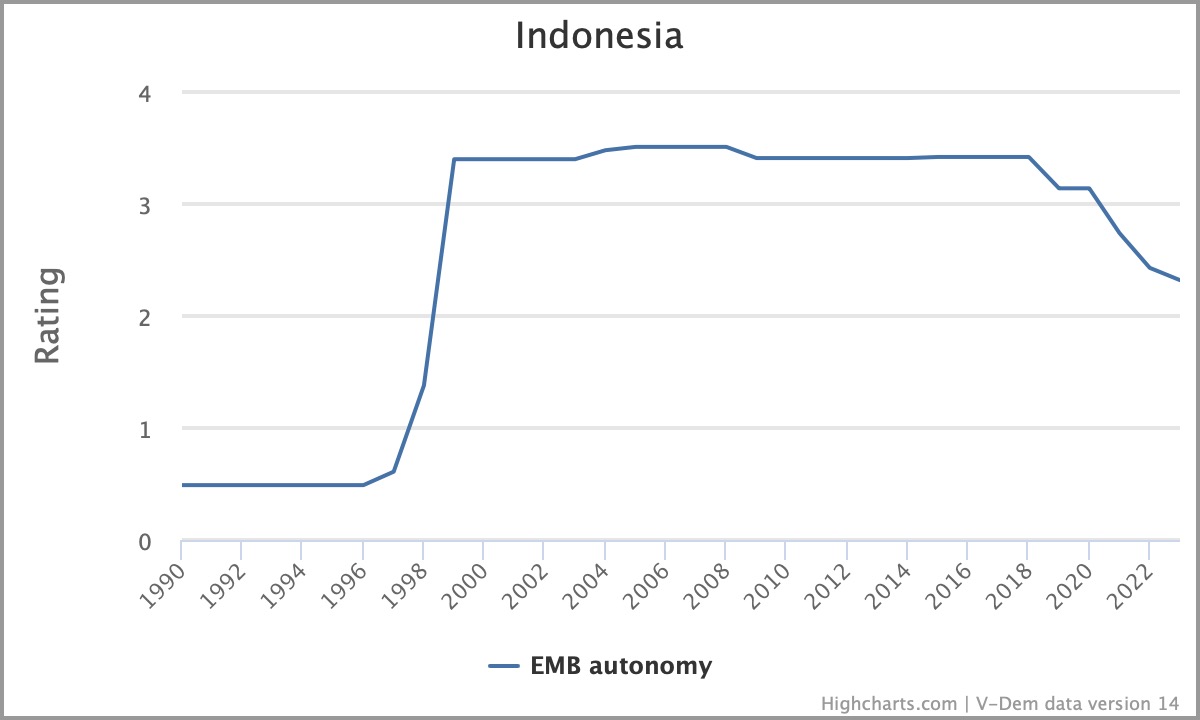

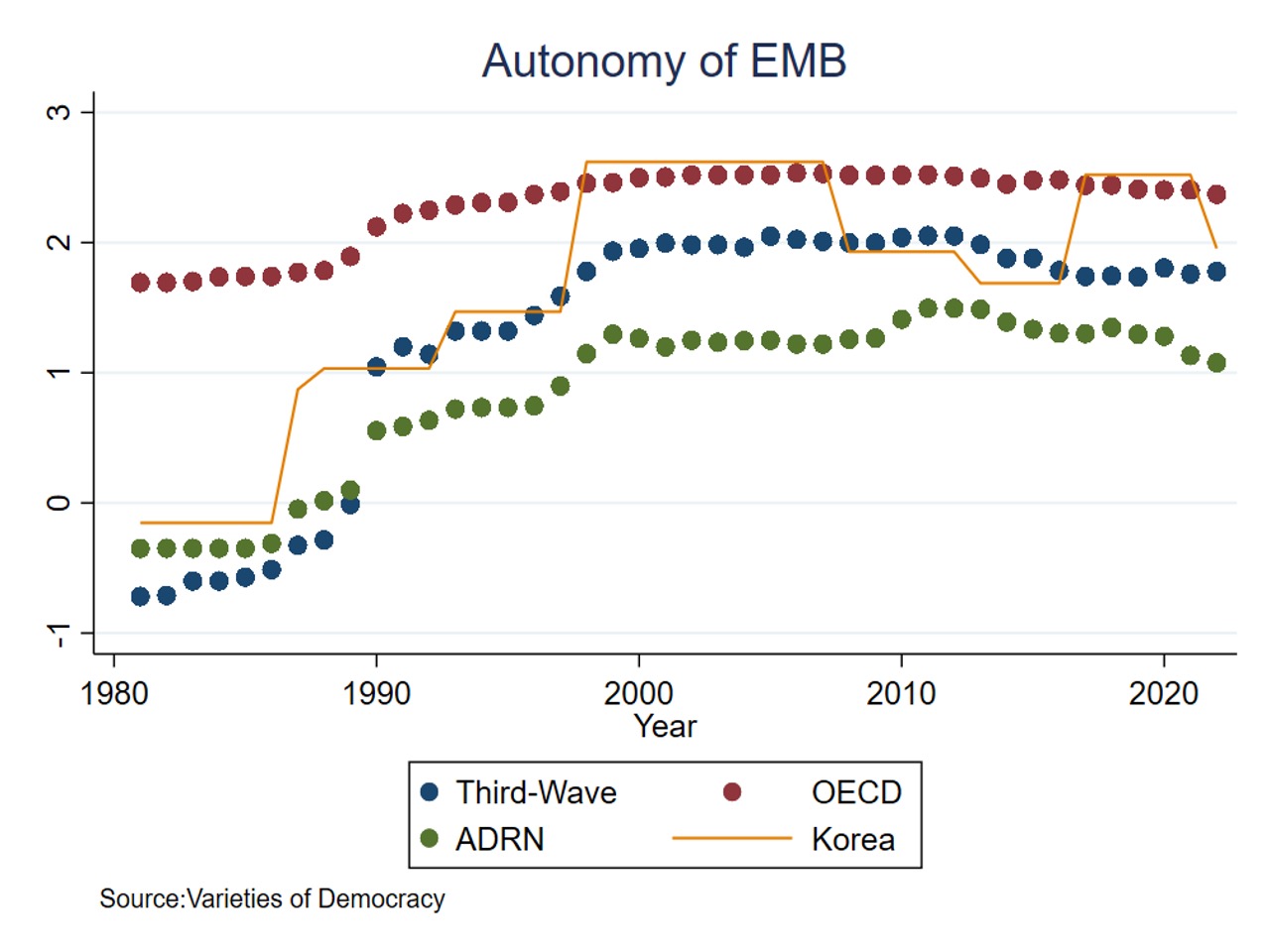

3.2. EMB Autonomy is No Longer Independent

Since Indonesia entered a democratic transition period in 1998, the government has agreed that election organizers must act as autonomous institutions, free from the influence of any party, including the president as head of state and head of government, as presented in the provisions of Article 22E paragraph (5) of the constitution which states firmly that the KPU is national, permanent, and independent. Law No. 15/2011 on Election Organizers further reaffirms this regulation. However, in practice, EMB, as an autonomous institution, finds it difficult to maintain its independence from the influence of the president or parliament, which can be seen from the 2024 election when there were allegations of the president interfering in the implementation of the election and the KPU’s requirement to consult and implement DPR recommendations in making KPU regulations.[3]

Other electoral management bodies do not face the same struggle as KPU to hold its autonomy. In this regard, Indonesia has three institutions that function as election management bodies, namely the General Election Commission (KPU), the Election Supervisory Body (Bawaslu), and the Election Organizer Honorary Council (DKPP). The three are distinguished based on their authority: The KPU carries out the role of election organizers, while Bawaslu and DKPP carry out the supervisory role where Bawaslu supervises the implementation of elections by the KPU, and DKPP oversees the ethics of the election management body including the KPU and Bawaslu. Therefore, the autonomy to apply election laws and adm?nistrative rules impartially in national elections is more determined by the roles of KPU as the holding authority of election organizers.

In Indonesia, the constitution and election laws guarantee the autonomy of the KPU. Based on the typology of the electoral management body classified by IDEA International, the KPU was designed to adopt the independent model to prevent government intervention, especially by the president, due to its implementation during the Orde Baru era before reformation. The KPU was formed along with the implementation of the reform era elections in 1998; therefore, in that year, public trust in election organizers increased significantly. However, from the 2019 elections until the last election in 2024, many issues showed that the KPU is no longer able to maintain its independence in organizing elections. In the 2019 election, one of the election participants was the incumbent president, which led to a growing public perception that the KPU could no longer claim to be neutral.

The KPU was increasingly unable to uphold its principle of autonomy following the former president’s intervention in the 2024 election, helping Prabowo and Gibran Rakabuming Raka win by openly supporting the candidates during the electoral campaign period. In other words, in two recent elections, the public doubted the KPU, claiming that the KPU no longer has the autonomy to act impartially during election phases and may be influenced by the president as the head of executives and the head of government. This kind of influence affected the way KPU implemented the election laws and adm?nistrative rules toward the election candidates. This condition caused a decline in the EMB autonomy index in Indonesia, as presented in the graph below.

Figure 3. EMB Autonomy in Indonesia

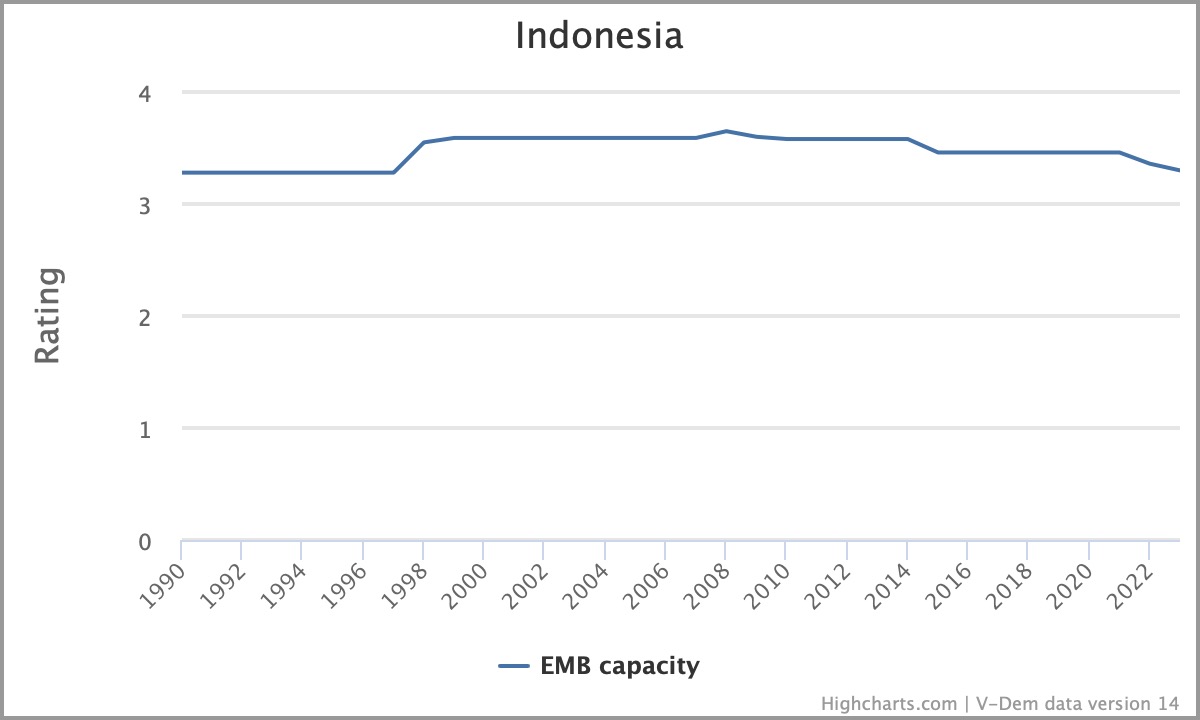

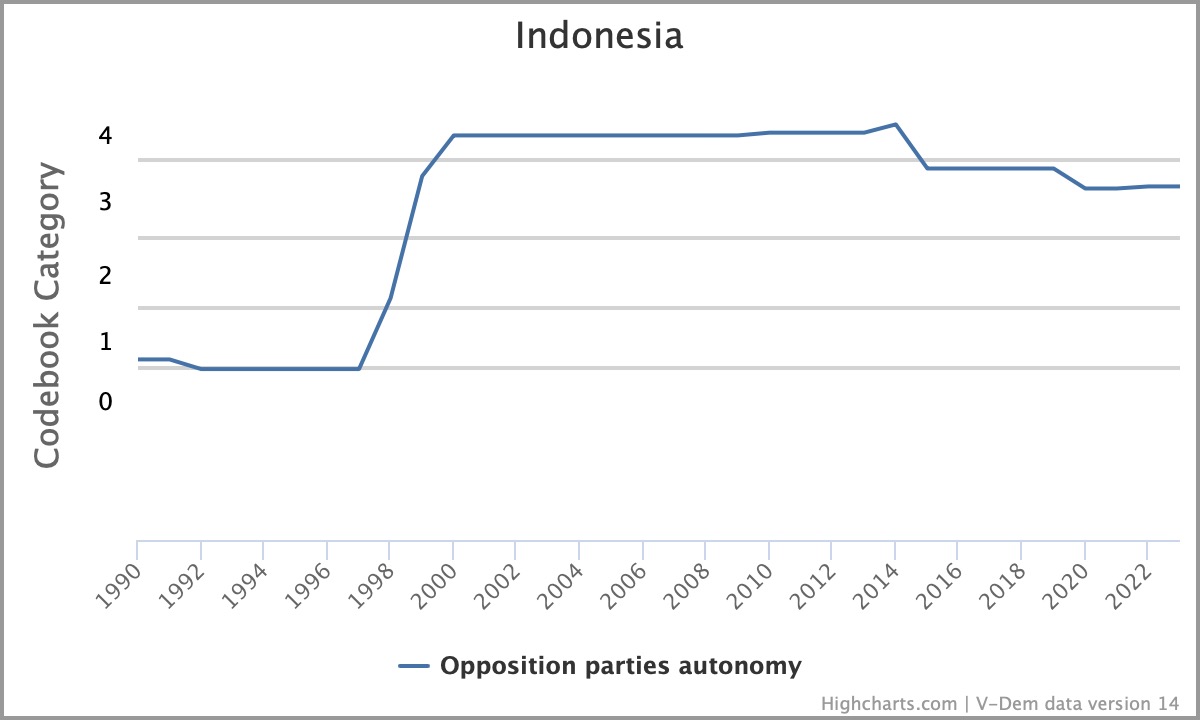

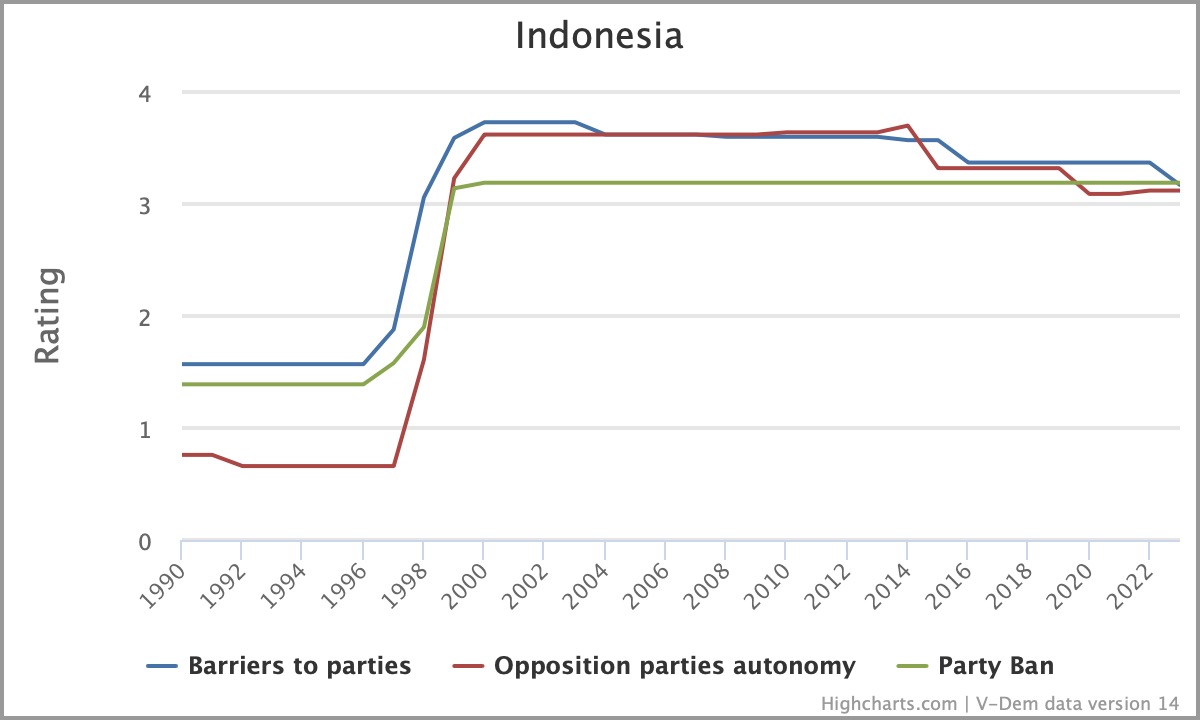

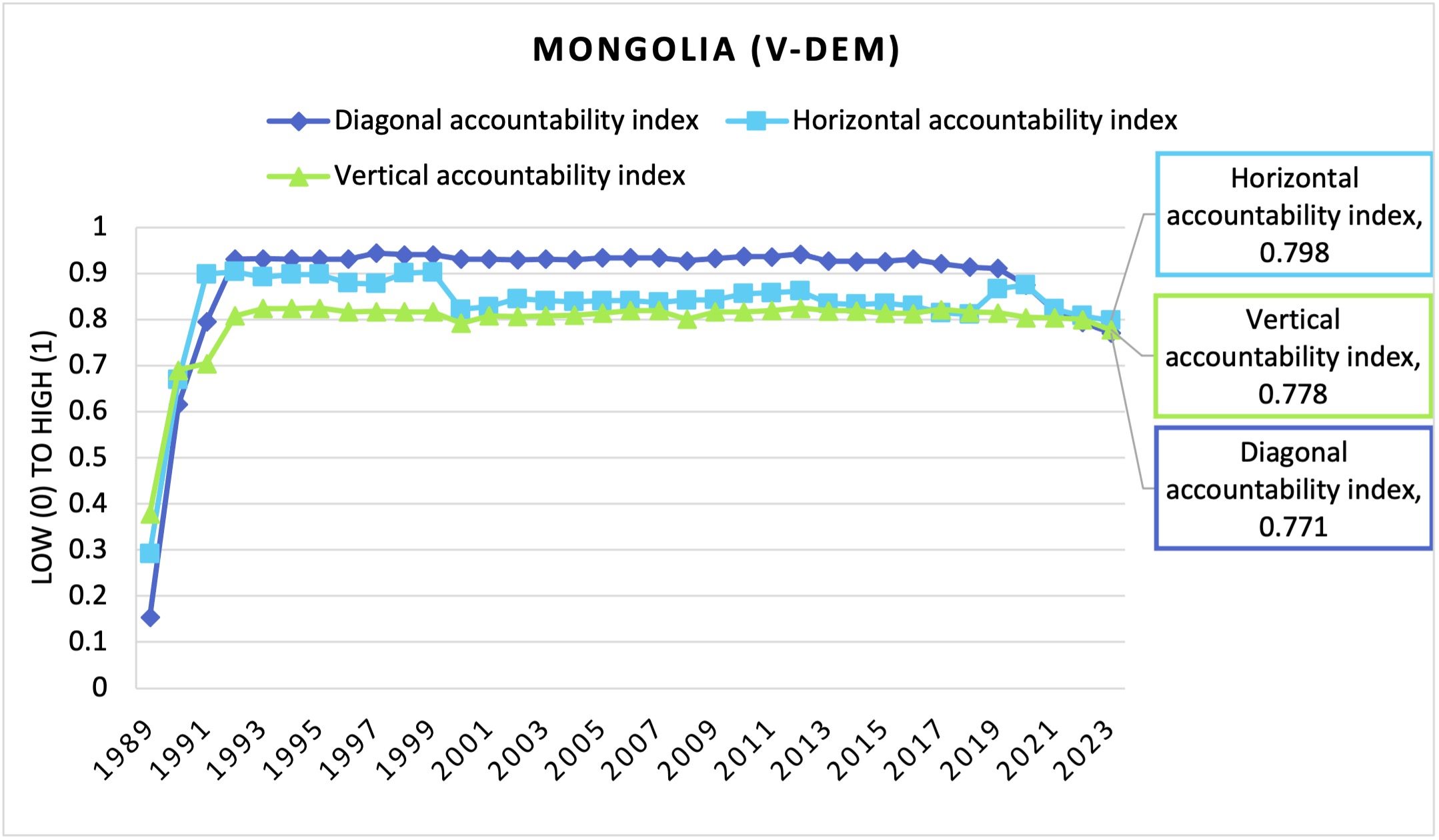

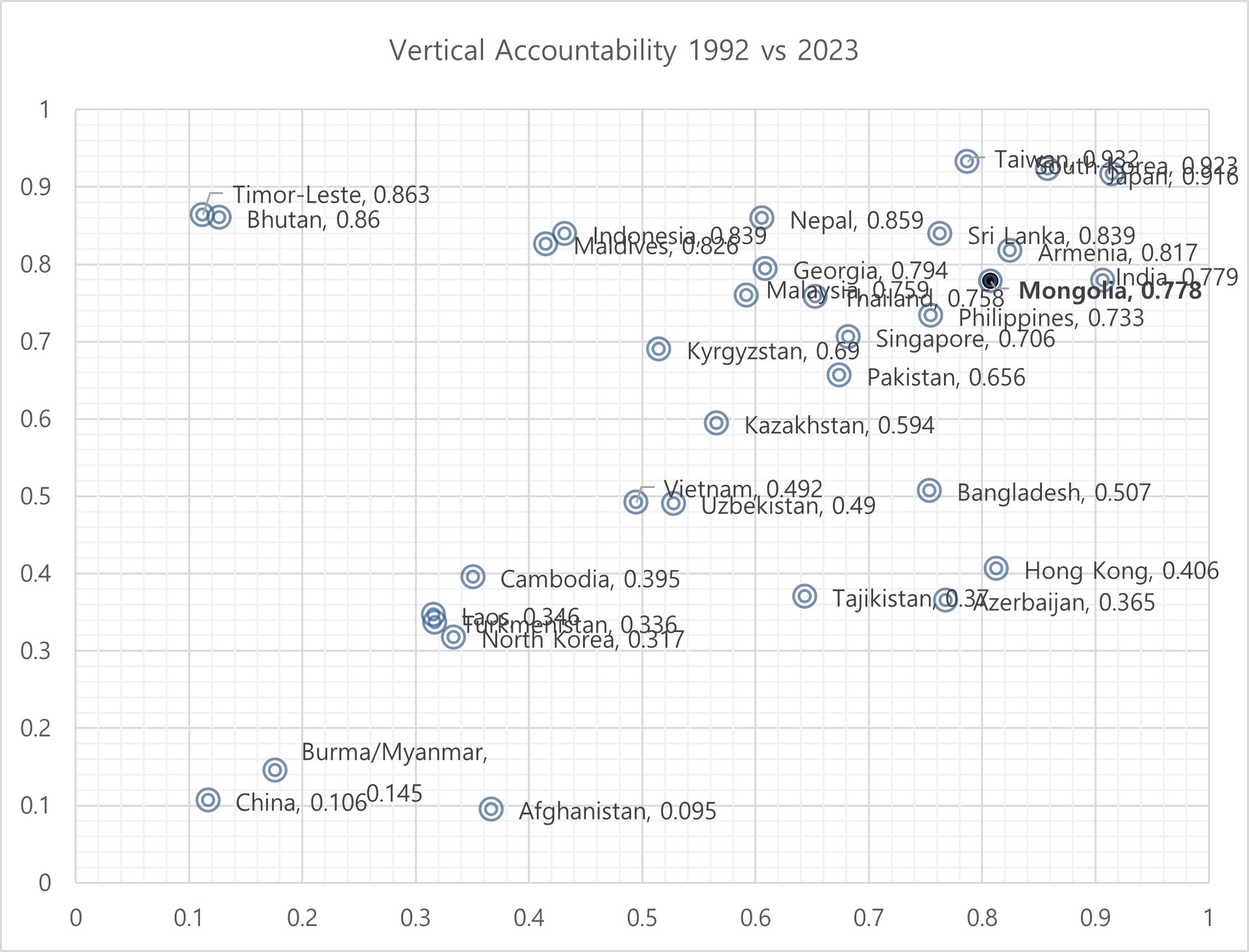

3.3. EMB has High Capacity but is Prone to Intervention