I. Introduction

Throughout the 20th century, Japan and Korea maintained a complex and contradictory relationship in terms of politics and economics. While Japan, which initiated modernization earlier, had established a modern state and capitalist economy in Asia since the late 19th century, Korea joined the wave of modernization in the early to mid-20th century. The 20th century was a period for both countries to move towards a leading position in the global order. In the 21st century, the time gap between Japan and Korea’s socio-economic development has narrowed, while both countries face future challenges. Among the crises and challenges faced by both countries in the 21st century, population crisis coming from low birth rates and an aging population are particularly difficult issues. The population crisis is difficult to solve and its impact is widespread.

Sociologist Chang Kyung-seop argues that Korea fell into the trap of compressed modernity as it underwent rapid growth (Chang 2022). Both Korea and Japan exhibit characteristics of compressed modernity, and the population crisis for both countries is a product of compressed modernity. Compressed modernity emphasizes not only that modernization proceeded rapidly but also that the process of modernization was uneven and contradictory. The burdens of this unevenness and contradiction were borne by individuals and families, not by social systerns or governments. The sustained decline in fertility rates in Korea and Japan, although at different times, is attributed to this compressed modernity. Aging is not only a biological process but also a socio-economic process, especially a result of compressed modernity.

Responding to social problems involves both resolution and adaptation. Even in the case of the population crisis caused by low birth rates and an aging population, resolution and adaptation are needed simultaneously. In this article, we focus more on the aspect of adaptation to the population crisis rather than resolution. Raising the birth rate is important as a solution to the population crisis. However, even if the birth rate rises immediately, the effects of hitherto low birth rate will continue for quite some time, and adaptation to it is very important and necessary.

In this article, we focus on two aspects of overall social adaptation to the population crisis: pension systern issues and local extinction. We examine trends and responses to these issues in Korea and Japan so far, and discuss how Korea and Japan can respond together in the future.

II. Population Crisis and Problems in Korea and Japan

Demography explains demographic transition as part of modernization as follows (Kirk 1996). A traditional society with high birth and death rates maintains a stable population, but when the standard of living improves and medical technology develops, the death rate decreases while the birth rate remains constant, resulting in a rapid increase in population. This rapidly increasing population leads to a crisis of overpopulation as argued by Malthus. As modernization progresses, however, the birth rate decreases, and a balance between low birth and low death rates is achieved, resulting in a stable population again. Countries in Europe and North America have generally followed this pattern of demographic transition.

However, the countries that joined modernization later, such as East Asian countries including Japan and South Korea, did not follow this pattern of demographic transition (Zaidi and Morgan 2017; Atoh et al. 2004). In these countries, modernization started later than the West, and the process was accelerated. A good example is economic growth, and another is demographic transition. Life expectancy increased rapidly, as did the decline in birth rates. In addition, Korea, Japan, and East Asian countries experienced more dramatic change compared to the West. Both the decline in death rates and the decline in birth rate was extremely large. This extreme and rapid change has exacerbated demographic transition, the result of which is a crisis of rapid aging and population decline.

Korea and Japan currently belong to the group of countries with the longest life expectancy in the world. In 2022, Korea’s life expectancy was 83.5 years, and Japan’s was 84.7 years, significantly higher than the OECD average of 80.5 years. High life expectancy increases the proportion of older people living long lives, leading to an overall aging of the population. However, it is the fertility rate that has a more significant impact on the aging of the population. Sharp decline in the influx of new population through childbirth results in a decreasing proportion of young people and a rapidly increasing proportion of the elderly.

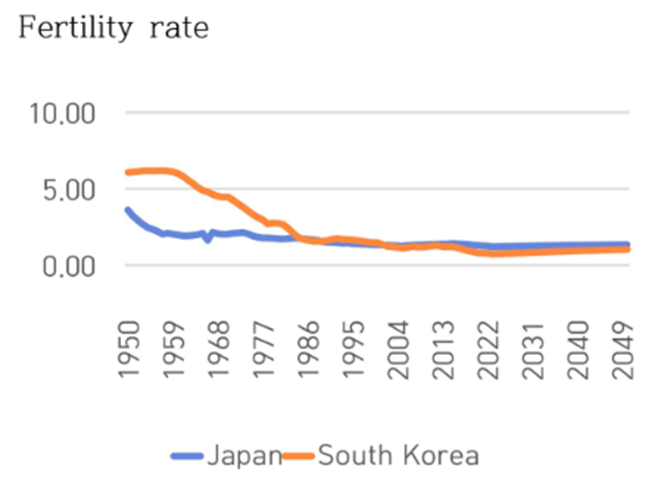

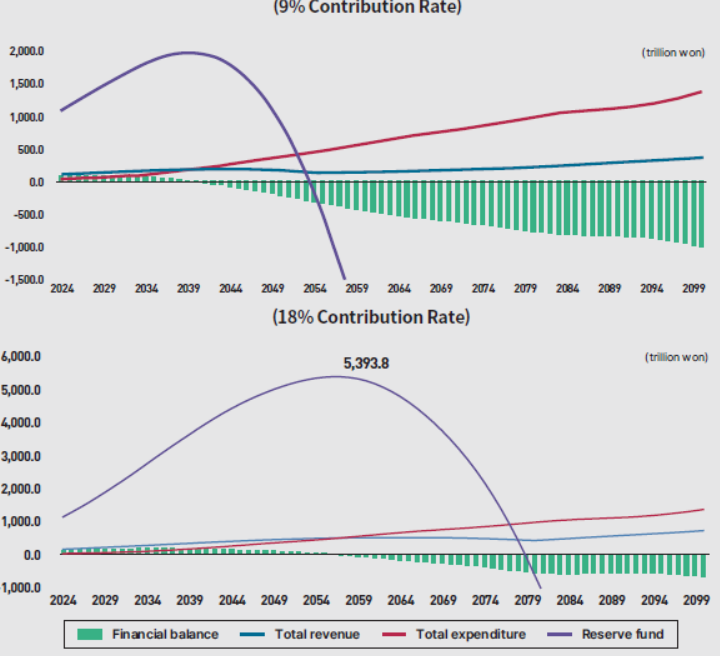

Korea and Japan not only have the highest life expectancy but also the lowest fertility rates (OECD 2023). The next graph shows the changing fertility rates in Korea and Japan. The fertility rate of Japan, which remained high due to the encouragement of childbirth during World War II and the postwar baby boom, dropped rapidly after the war. In contrast, South Korea’s total fertility rate was still high enough to exceed 6 until the beginning of modernization in 1960, but has since continued to decline. In Japan, birth control was introduced with concerns about an excess population during the economic difficulties after the war. In Korea, birth control was implemented semi-compulsively under the name of family planning projects with the advice of international organizations and government encouragement. Japan’s fertility rate fell below the replacement level of 2.2 in 1960, but has remained higher than 1.2 until 2020. On the other hand, Korea fell below the replacement level in 1983 and has consistently stayed around 1.2 in the 2000s, before dropping below 1.0 in 2018.

[Figure 1] Fertility rate of Japan and South Korea: trend and projection

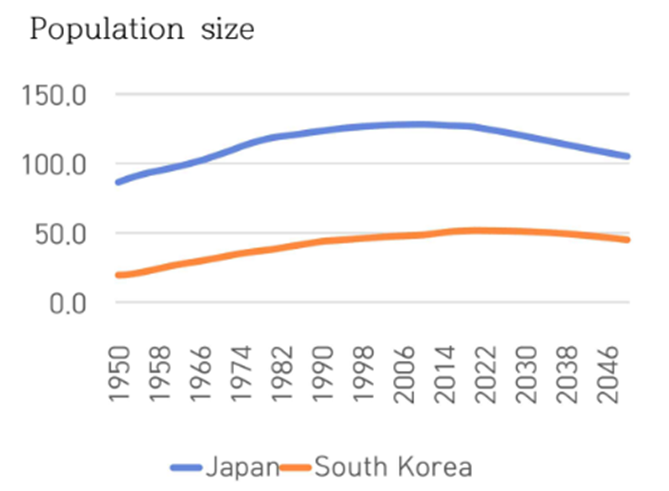

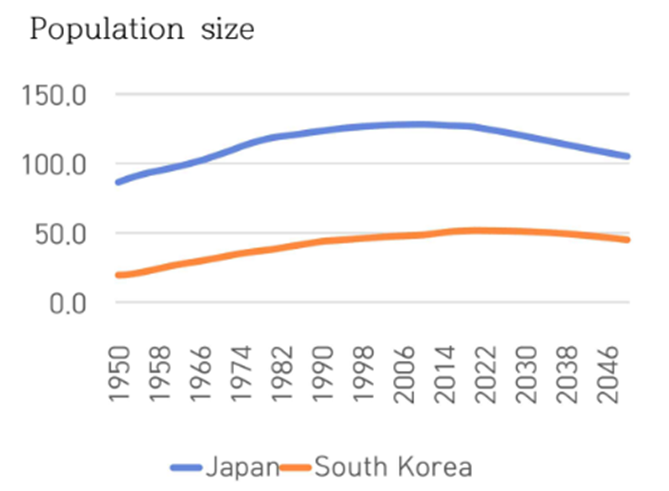

The effect of low birth rates is temporarily offset by the extension of life expectancy, but ultimately, the population growth slows down and then declines. As shown in the next graph, Japanese population decline began in 2005 when deaths exceeded births, and the total population decline, including foreigners, started in 2010. In Korea, population decline started in 2020, 15 years later than Japan, but the total population, including foreigners, has recently increased, so population decline is not yet a serious problem.

[Figure 2] Population size of Japan and South Korea: trend and projection

According to population prediction, the total population of Japan in 2050 is expected to be 14.68 million and the total population of Korea is expected to be 4,234 million, 81.7% of each country’s population just before population decline. Considering Korea’s current ultra-low fertility rate, Korea’s population decline after 2050 is expected to proceed much faster than Japan’s.

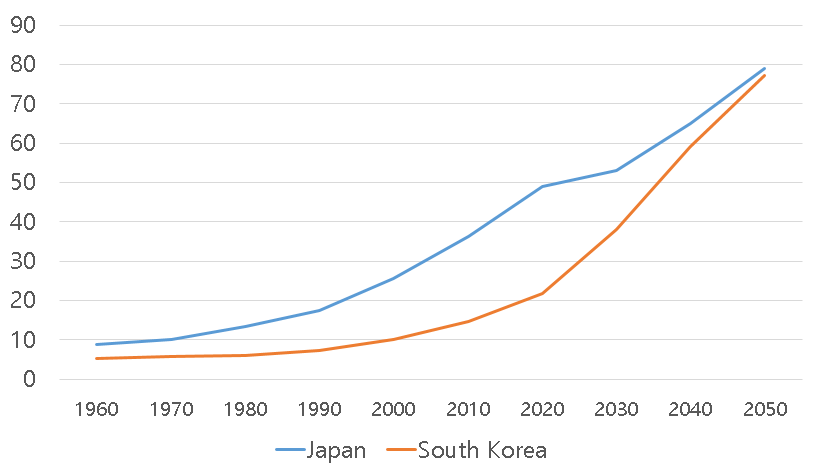

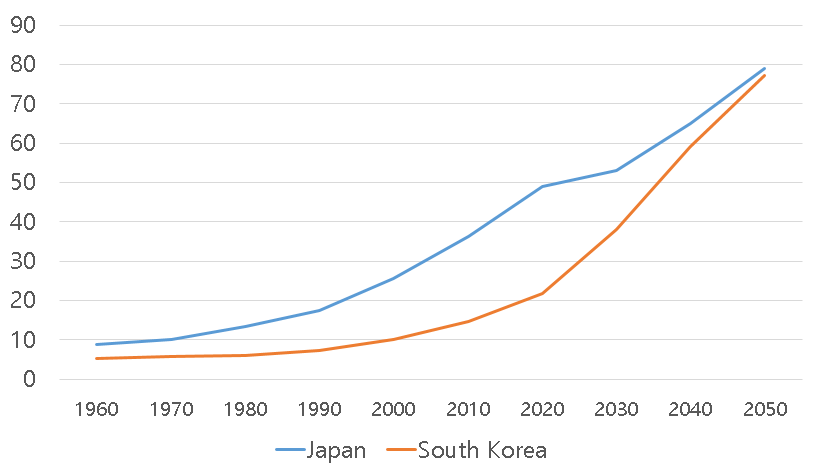

However, by 2050, the core of the population crisis is not the size of the population but the composition or distribution of the population. Rapid decline in the influx of young people and the increasing lifespan of the elderly disrupt the balance of the population and send ripple effects on the economy and society as a whole. The figure below shows the trend of the elderly dependency ratio, the number of elderly people aged 65 or older that one hundred people of working age must support, for Japan and Korea. Around 1960, when Japan’s postwar revival was in full swing and Korea’s economic development began, the elderly dependency ratio was 8.9 in Japan and 5.3 in Korea. The low elderly dependency ratio provided favorable conditions for economic development, and Korea and Japan enjoyed the population premium in economic development. The elderly dependency ratio began to rise sharply in the 1990s for Japan and in the 2010s for South Korea. Currently, Japan’s elderly dependency ratio exceeds 50, and Korea’s exceeds 20. As Korea’s elderly dependency ratio increases rapidly, both Korea and Japan are expected to approach 80 by 2050.

[Figure 3] Old age dependency ratio of Japan and South Korea: trend and projection

Overall, the population crisis in Japan and Korea is characterized by an aging population and ultra-low fertility rates since the mid-20th century, accompanied by a sharp increase in the elderly dependency ratio and population decline. The economic impacts of this population crisis can be summarized as follows:

First, there will be a shortage of labor due to a population decline, particularly the working-age population. Responses to this problem include utilizing robots and AI, utilizing idle workforce, extending retirement ages, and increasing immigration from abroad.

Second, there will be a fiscal crisis caused by a rapid increase in social welfare costs on aging population. The increase in the elderly population not only increases medical costs but also threatens the pension systern for living after retirement. Responses to this problem include reforming the pension systern to enhance its sustainability and extending retirement ages and delaying the receipt of pensions.

Third, there is the issue of local extinction caused by the concentration of young people in metropolitan areas. As young people flock to big cities, the fertility rate in rural areas is significantly lower than in urban areas, and rural areas are at risk of extinction. Responses to this problem include maintaining the local population by increasing the influx of foreign workers, among others, and consolidating local administrative districts.

In this article, we focus on the second and third problems and explore Japan and Korea’s responses to them, seeking directions for cooperation between Korea and Japan to prepare for 2050.

III. Pension issues and responses in Korea and Japan

Though the Japanese pension systern began in the late 1930s, but a universal pension systern for all citizens was introduced after the enactment of the National Pension Act in 1959 (Nomura 2019). After the introduction of the Welfare Pension for employees, the National Pension for the general public, including self-employed individuals, emerged in 1961. Although the pension systern was divided between employees and the self-employed, Japan’s pension systern is characterized by a large government subsidy. Japanese government has continuously increased the share of national expenditure in pensions to appease public dissatisfaction several times to resolve financial crises in the pension systern throughout the latter half of the 20th century.

The pension systern for civil servants was introduced in 1960, followed by the systern for military personnel in 1963 and for private school teachers in 1974. Although the National Pension Act was enacted in 1973, the actual pension systern began with the amendment of the National Pension Act in 1986 and the introduction of the pension systern for employees in 1988 ( Yang 2023). In 1995, pension systern included farmers and fishermen, and in 1999, a pension for urban residents was introduced, covering the entire population. There has been little government subsidy to the national pension in Korea so far. This contrasts with the substantial government contributions to the pension systern in Europe and Japan.

Japan’s National Pension initially operated on a fully funded systern, but has since shifted to a pay-as-you-go systern. Korea’s National Pension is also fully funded in principle, but in reality, it is a partially funded systern that may shift to a pay-as-you-go systern in the future due to the pressure of ageing population.

The problem with all national pensions is that pension fund may deplete if the number of beneficiaries increases while the number of contributors decreases. This is inevitable, especially in countries like Japan and Korea where aging is rapidly progressing due to ultra-low birth rates. When the national pension systern shifts from a fully funded systern to a pay-as-you-go systern, the issue of intergenerational equity arises. This is because a large number of elderly people enjoy comfortable retirements through pensions, while a smaller number of younger generations bear a heavier pension burden and their future pension benefits are at risk (Klein and Mosler 2021).

To address these issues, the response is to delay the eligibility age for pensions and lower the income replacement rate, meaning less money is received and pension contributions increases. However, the problem is that the public is not willing to accept such proposals of increasing current pain to avoid future crises.

In Japan, during the high growth period of the late 20th century, pension payments were increased to match inflation and wage increases to ensure income security. However, since entering a period of low growth, Japan has made efforts to increase the sustainability of the pension systern. As a result, in 1994, a systern to gradually raise the pension eligibility age from 60 to 65 was introduced through amendments to the pension act, and this is still ongoing. However, this is still lower than in other developed countries, so such reforms were not very effective (Higo 2021). In 2022, a plan to further delay the pension eligibility age from 65 to 75 was announced. Additionally, in 2004, the Koizumi administration implemented reforms to increase the pension contribution-to-income ratio from 13.9% to 18.3% by 2017.

Despite these efforts, Japan’s pension systern still faces many risks. Most importantly, although the contribution rate to the national pension has been raised, the government’s burden is still heavy. Furthermore, when we look at the overall social security systern, the real problem lies in that the share of expenditures in social security costs related to the elderly is high, making it inevitable that the fiscal burden will continue to increase (Jung 2021). Japan’s social security costs increased from 5.8% of GDP in 1970 to 13.7% in 1990 and then to 32.8% in 2021. This ratio is expected to exceed 40% by 2050, accounting for the largest part of Japan’s fiscal burden.

The rapid increase in Japan’s social security costs is driven by the fact that two-thirds of social security costs are related to the elderly (Jung 2021). In addition to pensions, medical care costs, and other welfare services costs are all increasing rapidly with population aging. The lack of an increase in the tax burden rate despite the continued increase in social security spending further contributes to the increase in fiscal problem. Despite the steady increase in social security spending, the tax burden rate has not actually increased since 1990. As a result, the scale of Japan’s long-term government bonds has rapidly increased, reaching 225% of GDP by 2020. Moreover, the tax revenue has not increased since 1990 due to low growth, while government spending has continued to increase. The largest portion of current government spending is social security spending, accounting for more than half of it, and two-thirds of it is related to the elderly (OECD 2023).

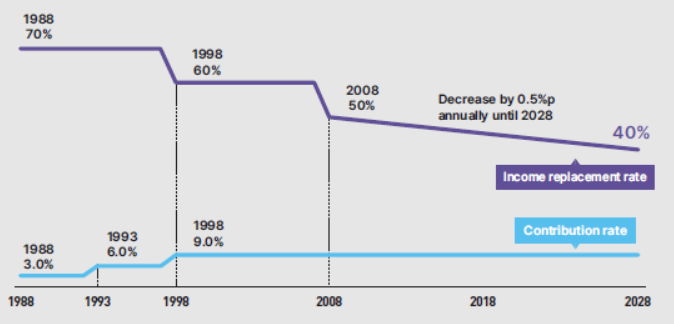

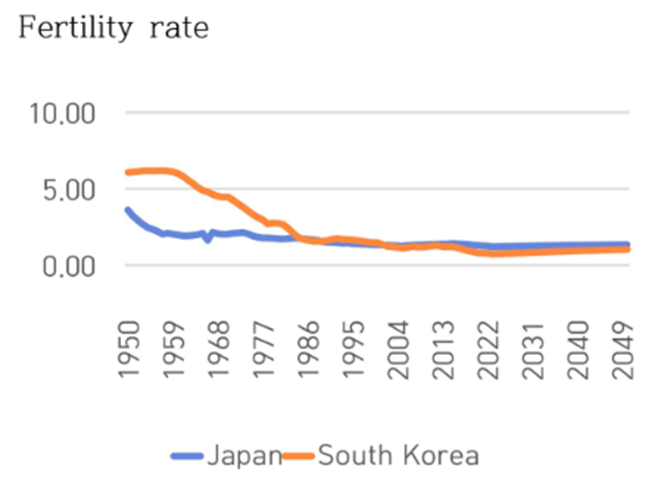

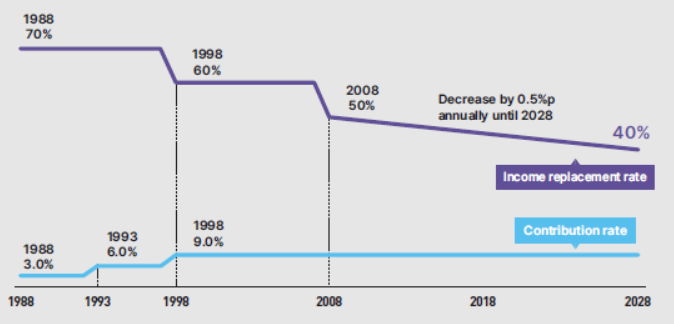

In Korea, there are similarities and differences compared to Japan. All employees and self-employed individuals are included in the same national pension systern in Korea, unlike Japan’s separate pension systerns for employees and the self-employed. When the Korean National Pension systern was launched in 1988, it was designed unrealistically with a high income replacement rate of 70% and a very low contribution rate of 3%. Since then, several revisions have been made, and the current income replacement rate has been lowered to 40%, and the contribution rate has been increased to 9% (Yang 2023). However, it still falls short of half of Japan’s 18.3%. This pension systern is sustainable only under the assumption that the population continues to grow.

[Figure 4] Korea’s National Pension Plan Contribution & Replacement Rates

Source: (Lee and Shin 2024).

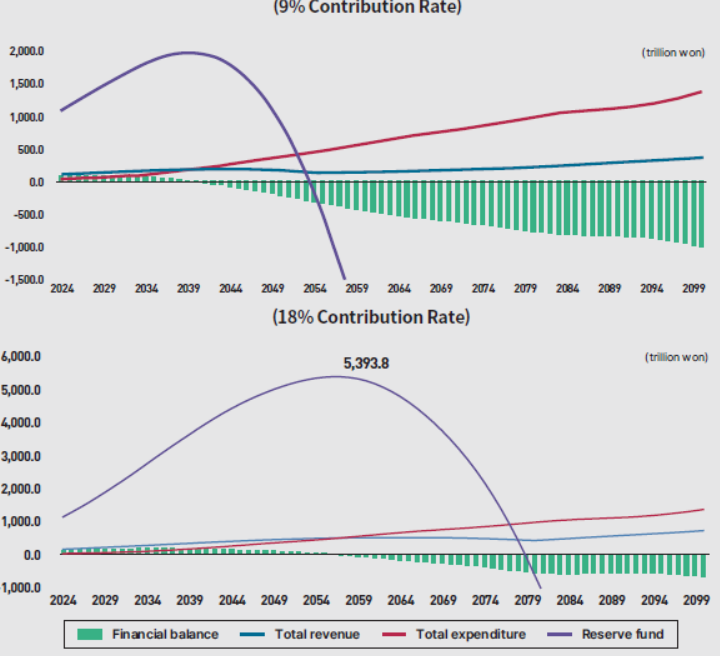

However, this systern becomes not sustainable if the population declines and the proportion of elderly people increases rapidly (Lee and Shin 2024). South Korea’s pension eligibility age has been 60 since its inception, and it will gradually increase to 65 by 2033, starting in 2023. There are voices calling for a higher retirement age in South Korea, with one of the highest life expectancies alongside Japan. A pension systern is unsustainable if the expected rate of return is higher than 1, meaning there are more benefits from than contributions to the systern. Especially in a country like South Korea, with little subsidy from the government, relying solely on the pension fund can lead to fund depletion. The figure below shows a projection of when the fund will deplete if the current premium rate of 9% continues and if the premium rate increases to 18%, comparable to Japan. If the current premium rate is maintained, the pension fund will be depleted in 2055. If we do not reduce the income replacement rate, which is the basic purpose of pensions, we need to increase the premium rate, and if we increase the premium rate to 18%, the fund will be depleted around 2080.

[Figure 5] Projections for National Pension financial balance and reserve fund

Source: (Lee and Shin 2024).

The South Korean government has been discussing and debating pension reform for some time, with various reform alternatives, but no reform bill has yet been passed by the National Assembly. South Korea, like Japan, is on the verge of a significant increase in government spending on healthcare and other social security for the elderly. South Korean government spending on social security is currently 15.5% of GDP, lower than Japan’s, but is expected to rise to 26.9% by 2065. Overall reforms are needed to make the social security systern, including pensions, more sustainable.

IV. Rural decline and responses in Korea and Japan

The impact of aging is also evident in the spatial distribution of the population. Globally, industrialization and urbanization have led to a concentration of population in cities. In countries that have experienced compressive modernization, such as South Korea and Japan, this process has been even more rapid.

In Japan, the high growth period since 1955 has led to a concentration of population in three major urban areas: Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya. As a result, only eight of Japan’s 47 metropolitan areas grew in population during the high-growth period: Tokyo, Osaka, Kanagawa, Aichi, Hyogo, Saitama, Chiba, and Fukuoka. After the high-growth period ended, migration from rural areas to metropolitan areas generally eased, but the Tokyo metropolitan area continued to attract people. Since most of the people who moved to the cities were young people, the rural areas that lost population were left with not only a shortage of people but also a high proportion of elderly people (Jung 2021).

The same is true in South Korea, where the process of modernization and high economic growth has led to a concentration of population in metropolitan areas. Prior to high growth, the Seoul metropolitan area centered on the Gyeongbu axis and the southeast region centered on Busan established themselves as large cities. During industrialization, Daegu grew into a metropolis, and as a result of high growth, Incheon and Suwon became metropolises in the metropolitan area and Ulsan in the southeast. As in Japan, the Seoul-centered metropolitan area is the only one with sustained population growth after the high-growth period (Yim 1994).

Both South Korea and Japan have made efforts to revitalize rural areas as the concentration of population in large cities during the high-growth process has led to the shrinkage of rural areas. However, there have been little success. Especially since the 2000s, the crisis in rural areas has intensified as the birthrate has remained extremely low and the population has aged rapidly. As flight of young people to Tokyo and Seoul continued, a growing number of local governments failed to maintain the minimum population size to function as autonomous units. The difference between the rural crisis of the high-growth period and the current rural crisis is that while the problem of the past was the atrophy of rural areas, the current problem is the disappearance of rural areas.

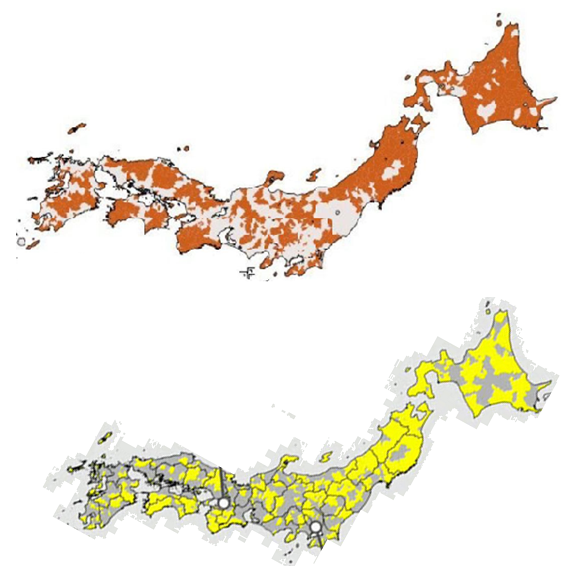

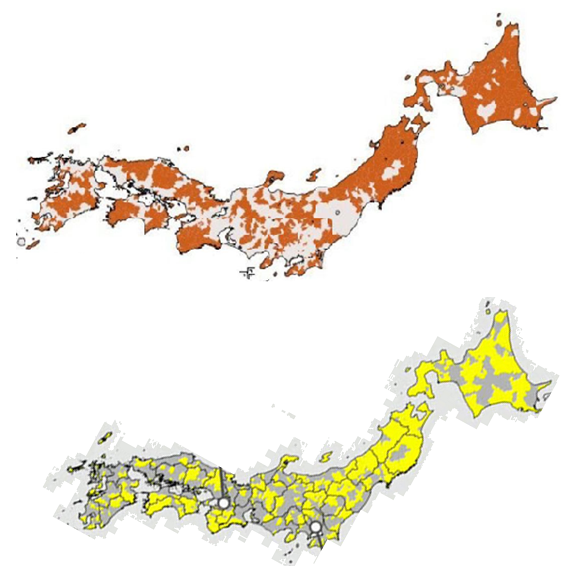

Japan’s municipalities have dwindled from nearly 70,000 to fewer than 1,720 in the 2000s, following major mergers during the Meiji, Showa, and Heisei periods. In 2014, a private organization called the Population Strategy Committee, led by Masuda Haroya, a former senior Japanese government official, calculated the percentage of basic municipalities at risk of disappearing by 2040. The risk of disappearance was calculated based on the percentage of women of childbearing age in the total population. In the figure above, the brown areas are those at risk of extinction as of 2014, totaling 896, or 52% of all basic municipalities. The figure below is based on the same 2024 data and shows that the number of at-risk areas in yellow is 744 (43% of the total), a decrease from 10 years ago (Suzuki 2024; Cho 2024). The main reason for the decrease is the migration of foreigners.

[Figure 6] Local municipalities at risk of extinction in Japan, 2040: Comparison of projection in 2014 (above) vs 2024 (below)

Source: (Population Strategy Council 2014; 2024).

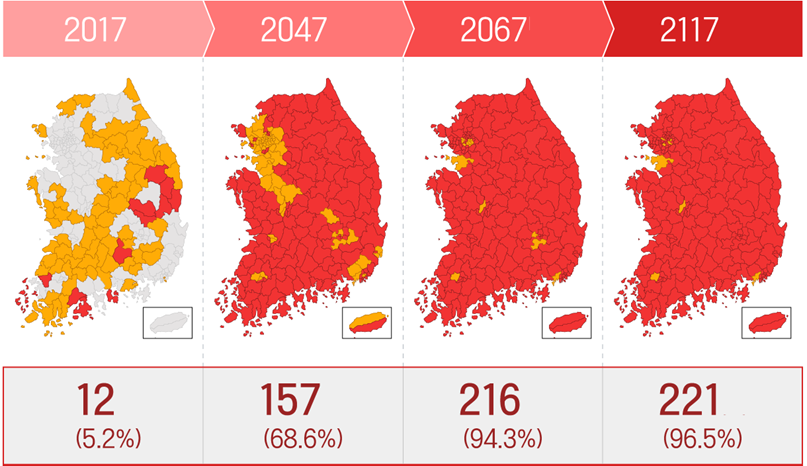

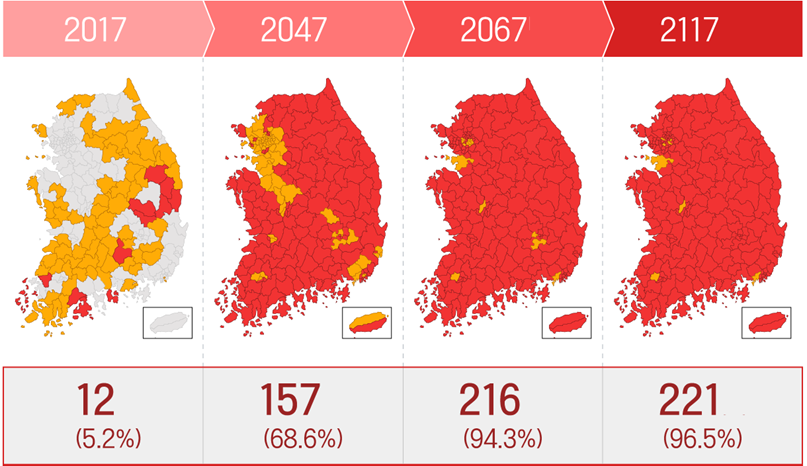

In South Korea, the situation is similar or worse than in Japan. The number of municipalities in South Korea has increased to 229 since 2010. South Korea’s National Audit Office calculated the proportion of basic municipalities at risk of disappearance due to future population decline, following the way Japan’s Population Strategy Commission calculated in 2021, and found that in 2017, there were 12, or 5.2% of the total, and that by 2047, 157 municipalities, or 68.6% of the total, will be at risk of disappearance if the current trend of rapid aging continues. Even more shocking is the result that after the mid-2060s, more than 90% of foundation municipalities will be at risk of disappearing (The Board of Audit and Inspection of Korea 2021).

[Figure 7] Projection of local municipalities at risk of extinction in Korea

Source: (The Board of Audit and Inspection of Korea 2021).

In both Japan and South Korea, rural decline is an imminent risk by 2050. Many policy reports on the risk of rural decline recommended increasing the fertility rate of rural areas, minimizing the outflow of young people, or maintaining the population through migration from abroad. However, these efforts have been already made in the past with little success. Other responses include focusing on regional hubs and merging municipalities to form larger cities. However, these changes require the consent and support of many residents.

V. Future Prospects for Cooperation in Addressing the Population Crisis in Japan and South Korea

We looked at the population challenges faced together by Korea and Japan: the crisis surrounding pensions and social security, and rural decline. Neither of these issues is easy to solve or respond to.

In the case of pensions and social security, Japan needs to lower the social security spending on elderly people and keep the balance of contributions and benefits to make pensions more sustainable. Similarly, South Korea needs reforms to increase premium rates to maintain income replacement rates. However, in Korea and Japan, where the elderly people are becoming a larger and larger share of the electorate, these reforms are likely to be made to improve intergenerational equity. Furthermore, it is possible that they will reject reforms to pension and social security systerns altogether.

In a socio-political climate of increasing gerontocracy, attaining reforms to promote intergenerational equity requires efforts to make young people interested in and participate in politics to ensure their voices are heard. However, the increasingly isolated and passive social climate for young people is making these efforts more difficult. There is a need for exchanges between young people in Korea and Japan, especially those aimed at raising awareness of their rights and revitalizing their political participation. Such constructive and forward-looking exchanges could be the first step toward more proactive social security and pension reforms to promote intergenerational equity.

The cooperation and trust between the central government, local governments, and local residents is crucial to preventing the disappearance of municipalities and revitalizing them. While the major merger of Japan’s municipalities in the past has faced many difficulties and opposition, the future expansion of municipalities will need to overcome many objections and complaints. This will require the streamlining of local governments and the ability to increase access to administrative and welfare services over large areas. It will also require administrative and business capacity to overhaul abandoned houses and facilities in rural areas. It would be beneficial for Japan and South Korea to create joint organizations to collaborate on rural revitalization, create business opportunities, exchange best practices, and make efforts to engage and interact with residents. The high level of mutual interest in popular culture and daily lives of South Korea and Japan provides favorable conditions for such exchanges.

Finally, learning and cooperation through the exchange of information and experiences between Japan and South Korea can be very helpful in responding to aging, not only at the local but also at the central government level. Both Japan and South Korea are moving toward a future of declining birthrates and aging populations that is unprecedented globally. So far, Japan has experienced aging ahead of South Korea, but if aging continues at the current pace, South Korea will have a more severe aging problem than Japan after 2050. If Korea and Japan collaborate on discussions and responses to aging at the civil society level, including academia, rather than just at the administrative level of government, it will be more productive and have a greater societal impact than if each country tries to solve its own problems. ■

References

Atoh, Makoto, Vasantha Kandiah, and Serguey Ivanov. 2004. “The Second Demographic Transition in Asia? Comparative Analysis of the Low Fertility Situation in East and South-East Asian Countries.” The Japanese Journal of Population 2(1): 42-75.

Chang, Kyung-Sup. 2022. The Logic of Compressed Modernity. Cambridge: Polity.

Cho, Sungho. 2024. “Japan’s Policy Responses to Municipalities at Risk of Extinction.”

Global Social Security Review (31): 101-113.

Higo, Masa. 2021. “Making Sense of Japan’s Retirement Reform: An International Perspective.” Res. Bull. International Student Center, Kyushu University (29): 1-11

Jung, Hyun-Sook. 2021. Japan, Country with Population Crisis (In Korean). Seoul: Espisteme.

Kirk, Dudley. 1996. “Demographic Transition Theory.” Population Studies 50(3): 361-387.

Klein, Axel, and Hannes Mosler. 2021. “The Oldest Societies in Asia: The Politics of Ageing in South Korea and Japan.” In Global Political Demography: The Politics of Population Change, ed. Hannes Mosler and Axel Klein, 195-217. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Lee, Kang-koo, and Seung-ryong Shin. 2024. “Korea’s National Pension: Structural Reform Measures.” KDI Focus, February 21.

Nomura, Akiko. 2019. “Japan’s Pension systern: Challenges and Implications.” Nomura Institute of Capital Markets Research.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2023. Pensions at a Glance 2023. http://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/population.html

Suzuki, Kohei. 2024. “Japan’s Local Governments and Governance Under Population Decline.” In Handbook on Subnational Governments and Governance, 193-207. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

The Board of Audit and Inspection of Korea. 2021. Responses to Structural Changes in Population. Audit Report.

Yang, Jae-jin. 2023. “The Developmental State, Export-Oriented Industrialization, and South Korea’s Social Security systern.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance and Public Management for Social Policy, 219. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yim, Seok-Hoi. 1994. “Problems of Administrative Area systern in Korea and Reforming Direction.” Journal of the Korean Geographical Society 29(1): 65-83.

Zaidi, Batool, and S. Philip Morgan. 2017. “The Second Demographic Transition Theory: A Review and Appraisal.” Annual Review of Sociology 43(1): 473-492.

■ Joon Han is Chair of Innovative Future Research Center at the East Asia Institute and Professor of Sociology at Yonsei University.

■ Typeset by Chaerin Kim, Research Assistant

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | crkim@eai.or.kr

![[Korea-Japan Joint Work on the World 2050] ⑩ How can South Korea & Japan Overcome the Impending Population Risk Together?](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/2025040114216395366503.png)

![[ADRN Working Paper] Democratic Backsliding in South Korea](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250702151055558995988(0).jpg)

![[ADRN Working Paper] The Impact of the Millennials and Gen Z on Democracy in Northeast Asia](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/202505231731371005535793(0).jpg)