![[Korea-Japan Joint Work on the World 2050] ⑧ Prospects of Cooperation between Japan and Korea toward Carbon Neutrality](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/2025040114225395366503.png)

[Korea-Japan Joint Work on the World 2050] ⑧ Prospects of Cooperation between Japan and Korea toward Carbon Neutrality

Korea-Japan Future Dialogue | Working Paper | 2025-03-14

Daisuke Harada

Project Director, JOGMEC

Daisuke Harada, Project Director at the Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security (JOGMEC), examines the future of South Korea-Japan cooperation on carbon neutrality, emphasizing the need for joint efforts to ensure energy stability while transitioning to a low-carbon economy. He highlights the importance of collaboration in key areas such as hydrogen and ammonia production, carbon capture and storage (CCS), and cleaner LNG practices. In light of Russia’s declining reliability as an energy partner after the Ukraine war, Harada stresses the urgency of reassessing energy security strategies. He underscores the need for South Korea and Japan to diversify energy supply chains, strengthen regional energy cooperation, and invest in decarbonization technologies to enhance resilience and economic security.

I. Response to Global Energy Transition

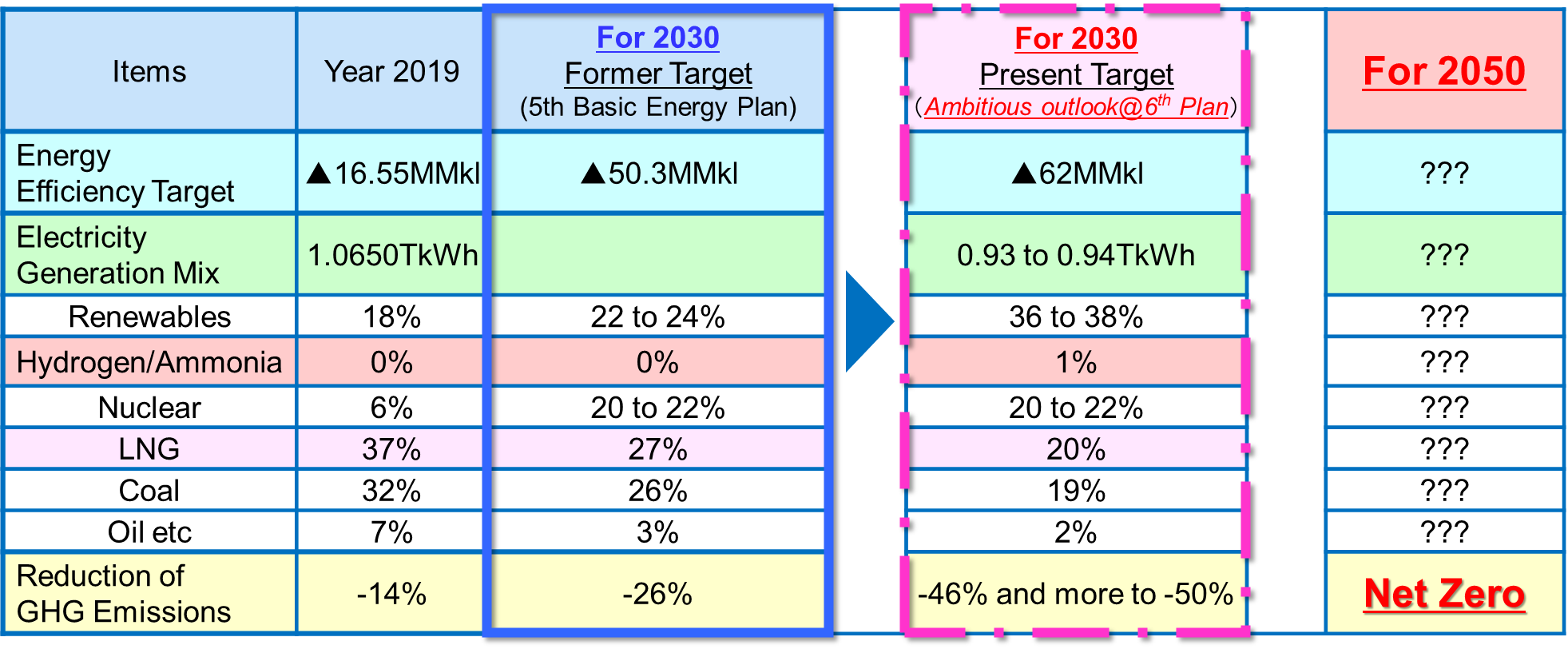

The Japanese government revises its energy plan about every three years (ANRE-METI 2018). The plan is formulated based on the Basic Energy Policy Law enacted in 2002. FY2024 is the year to formulate new 7th plan. The latest 6th one, approved by the Cabinet in October 2021 (see Figure 1), set goals for Japan’s energy mix to 2030 and presented various scenarios to 2050. The plan outlined nuclear energy to remain a key national energy source, as it predicted that it would account for 20-22% of the country’s electricity generation up to 2030. In addition, hydrogen and ammonia, new forms of energy that have recently captured public attention, have been newly added and estimated to contribute 1% to Japan’s generated electricity by 2030 (ANRE-METI 2022).

[Figure 1] Japan’s Energy Outlook for Primary Energy Supply in 6th Basic Energy Plan (2021)

While Japan is 70% dependent on the fossil fuel in its primary energy supply, the recent trend of de-carbonization, led by the EU initiative accelerated in 2020, also promoted Japan’s declaration of “Net-Zero by 2050,” which it declared to follow up other countries. This movement has been a huge earthquake not only for energy policymakers in the government but for most industries who will suffer by such drastic change even though there will be 30 years from now.

The utilization of energy, especially solar power, is restricted in Japan geographically, and wind power will be dependent upon a sufficient level of security against typhoon seasons. Hydro has already been fully exploited. Nuclear energy is currently a hot topic of discussion, particularly regarding how to reduce its use given forecasts predicting another mega-earthquake within 30 years. A realistic and concrete approach to realizing the goal of Net-Zero is required, even though the use of fossil fuels will remain inevitable in the future. The solution will involve energy saving (though this has limited potential for Japan) and diversification of energy sources such as hydrogen (ammonia), carbon-neutral LNG (or possibly ‘green oil’), and CCS/CCUS (not only blue hydrogen and ammonia but also exporting CO₂ by pipeline and by ship), as well as forest sinks (controversial but not negligible) and the purchase of emission rights from abroad.

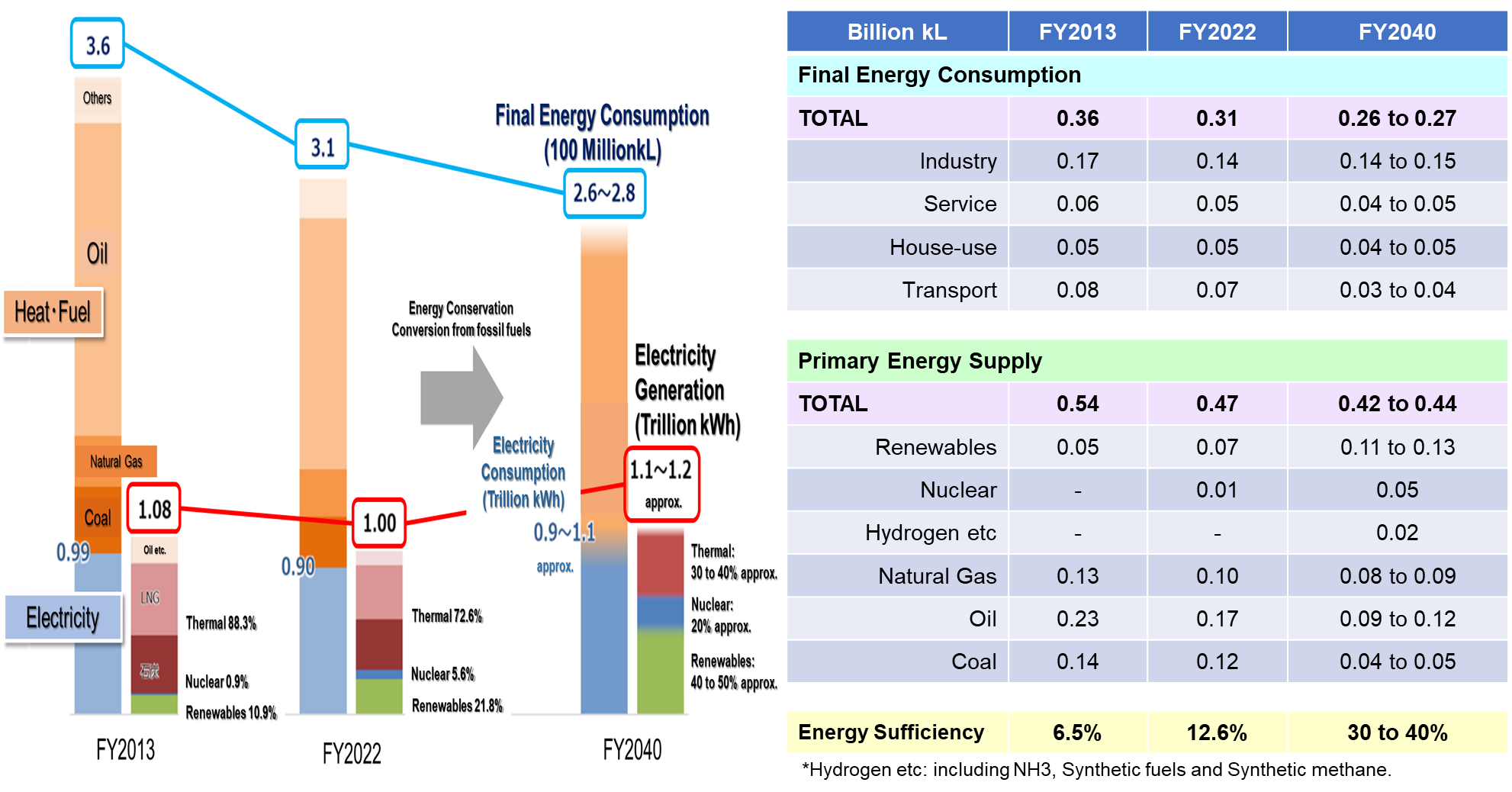

The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) of Japan has finally disclosed the draft of the new 7th Energy Basic Plan, including the outlook toward 2040 (METI 2024). It will undergo public comment in January before being approved by the government in February. The most noteworthy aspect of this draft is that it shows a shift toward maximum use of nuclear power generation. This is a major shift from the previous policy, which implied reducing Japan’s dependence on nuclear power as much as possible.

Regarding the 20% share of nuclear power generation in 2040 (see Figure 2), the important factor is not the share itself but the actual amount of power generated. The current plan’s target for 2030 sets a share of 20-22% of total power generation (0.93 to 0.94 TkWh, Figure 1). In that case, the amount of power generated by nuclear energy will be 180-200 billion kWh. However, this new draft indicates that nuclear power in 2040 will account for 20% of total power generation, equivalent to 220-240 billion kWh, indicating that nuclear power generation will increase by about 17-18% by 2040. This also indicates the possibility of not only restarting nuclear power plants but also constructing new nuclear power plants.

[Figure 2] Japan’s Newly drafted Energy Mix for 7th Basic Energy Plan (FY2024)

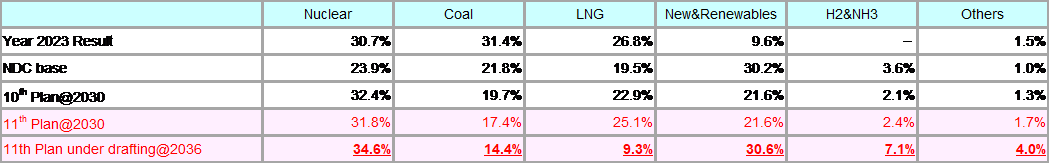

Korea is also now at a point where it needs to revise its Energy Basic Plan from the current 10th to the 11th. Both countries have been following a similar path since their energy situations are largely the same. While Japan’s outlook shows the primary energy mix as a base, Korea’s electricity mix shows trends that Japan is also moving toward, such as nuclear as the baseload, fossil fuels as the dominant energy source, and ambitious perspectives for hydrogen and ammonia as new energy sources (see Figure 3). Several sources say that the upcoming 11th Energy Basic Plan will outline Korea’s energy mix for 2036, and it is forecasted that LNG use in the electricity mix will further decline from the current 26.8% to 9.3%, quoting the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy’s statement: “Korea will rely more on nuclear power generation and renewables instead of fossil fuels and LNG. The balanced energy mix will advance the effective use of renewables to better achieve carbon neutrality (The Korea Times 2024).” This will be one of the controversial points and a key difference in the path that Japan and Korea take in the future.

[Figure 3] Korea’s Electricity Generation Mix Outlook by Source

※New & Renewables contains Fuel Cell. Others contains Heat Pump systern

The game has started to destroy and recreate the present structure and superiority in technology within a fossil fuel society. It seems that the EU’s prohibition of hybrid cars toward 2035 is the one of their strategies to change the market by excluding Japanese global companies such as Toyota and Honda, which have already had advanced and leading tech in those areas.

While hydrogen now becoming a star symbol of clean, future energy, we should also note that new forms of energy, such as green hydrogen, are not primary energy. They are primarily by-products that utilize other energy sources for production, which increases their price in comparison to primary energy sources. They are additionally still unreliable sources of energy in the contexts of security, supply volume, versatility, calorie by unit, and most importantly, economics (which includes problems of production, transportation, and stockpiling, which unanimously turn out to be highly expensive). If we choose to go for using hydrogen, we will lose our money as far as becoming a buyer. We should think it over how we can be a seller of hydrogen (upstream stakes) and its tech (for production and transportation).

There is always a possibility of the emergence of several factors that may put this global de-carbonization trend to an end or make it be forgotten, as we have already experienced in Kyoto-Protocol (agreed in 1997 and effective in 2005). The several factors can be: 1) If global cooling starts, 2) If Covid-19 is stamped out or there is a global acceptance of coexisting with the virus, 3) If world cannot be united in Net-Zero and each country recognizes unfairness on spending huge budget on realizing ‘Net-Zero’ without seeing and feeling climate improvements.

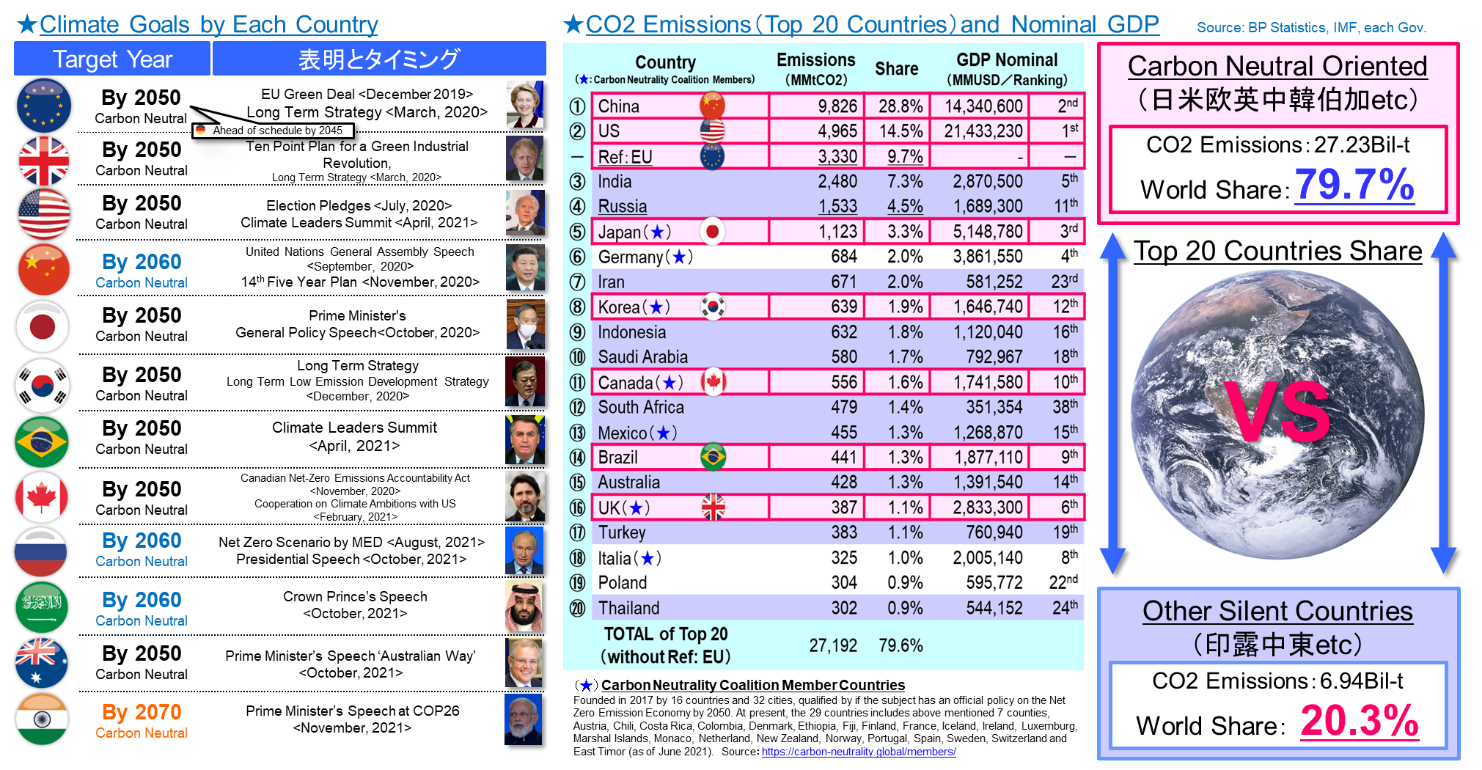

[Figure 4] Year 2020, the First Year of Carbon Neutrality

The COP26 summit was a significant event as it became a symbol of global commitment to decarbonization. On the other hand, it might also have marked the peak of excitement, as we did not see many other countries setting new carbon neutrality (CN) targets after the event, except Oman (October 2022). At this moment, over 80% of countries have set CN goals between 2045 and 2070. The remaining 20%, from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Middle Eastern countries, are still considering whether to join this very expensive millennium game. While 20% is a minority at this moment, the global population projection by the UN shows an increase from 8 billion to 10 billion by 2058, and this increase of 2 billion will mainly come from these 20% of countries.

The decarbonization flagship, the EU’s energy balance, will faithfully reflect the removal of fossil fuels and an increase in carbon-free sources instead. Through the transition, there will be difficulties to face, such as how long to rely on nuclear energy, the procurement of natural gas as a transition energy source and as a hydrogen source, disparities among EU member countries, and now unprecedented soaring energy prices following the Ukraine crisis. In Asia, on the contrary, not all countries are heading in the same direction for decarbonization, even though some countries have set goals for CN. In addition to the shift toward natural gas, cheap coal would continue to play a staple and important role in the energy mix for some large energy-consuming countries.

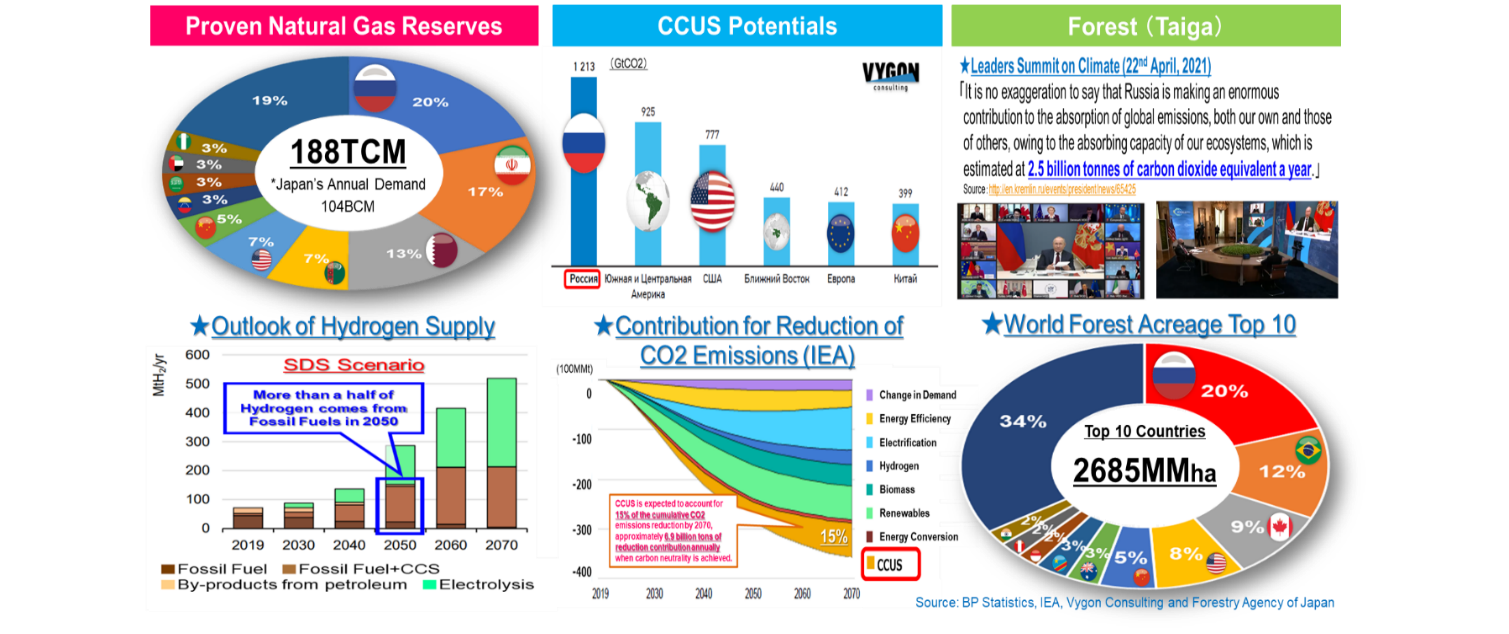

Russia was considered to keep the same importance for Japanese energy security as it does now for fossil fuels because new energy sources such as hydrogen (ammonia) are expected to be produced mainly from natural gas, as is done now. For Russia, the present decarbonization trend is not a threat at all. They believe that the global market will change, but some countries will still prefer cheaper fossil fuels, while others must buy expensive hydrogen from Russia. This represents new business opportunities for them.

In addition, Japan’s desired solutions, as written above, include not only hydrogen (ammonia) but also carbon-neutral LNG (or possibly ‘green oil’) and CCS/CCUS (not only blue hydrogen and ammonia but also CO2 export via pipeline and ship). These are dependent upon Russia’s potential. In other words, Russia is the only country that can provide such sources and solutions to Japan.

Moreover, Russia has started announcing and advertising its ability of the forest absorption of CO2 emissions (1.5billion CO2t emissions against 2.5 billion CO2t absorption by annum) (Presidential Office of the Russian Federation 2021). While there are discussions if it is true or not, it is obvious that Russia has huge potential to support Japan’s Net-Zero by 2050.

II. Toward the Future Beyond Ukraine Crisis

Japan is poor in energy resources and relies on imports from overseas for most of it. Ensuring energy security is the utmost importance to protect the living standards of the people, prevent economic activities from stagnation, and prepare for unforeseen contingencies. Diversification of supply sources (countries) and supply routes plays major efficient roles in strengthening energy security.

Over the past 30 years, especially after the Soviet Union collapsed, Russia had been recognized as a major oil and gas-producing country closest to Japan and as one of the most important countries with projects in which the Japanese government and Japanese companies participate as stakeholders in upstream operations. In addition, the Northern Sea Route, which has been utilized commercially year by year due to climate change, enables Japan to connect with the Arctic Ocean. The Arctic is the last resort of hydrocarbon potential on Earth, with abundant natural gas reserves that emit less CO2 compared with coal and oil and are expected to become the transition energy toward realizing a Net-Zero world. Also, natural gas is expected to serve as a future supply source of hydrogen. The Northern Sea Route has also been attracting attention as a new supply route that does not cross chokepoints or areas with high risks of disputes. Under these circumstances, Japan-Russia energy cooperation has been gradually deepening through upstream projects from Sakhalin in the 1990s, to East Siberia in the 2000s, and to the Arctic in the 2010s.

However, Russia’s invasion against Ukraine forced Japan to reconsider its strategy with Russia. As a member of the international community, Japan quickly aligned itself with the Western countries, and sanctions have expanded to the import ban of Russian oil, the core of Russia’s financial revenue just in three months after the invasion. While Japan still understands the importance of Russia in terms of energy security, showing a resolute stance to the world against Russia’s reckless act of ignoring international law is essential to protecting Japan’s national interests in the international community and much more important than the energy strategy with Russia, at least at this moment.

We must also pay attention to the fact that Russia, as a major oil and gas producing country, has now begun to take advantage of its impact on the oil and gas market in response to Western sanctions strategically. Until 2022, Russia was ‘the reliable energy supplier’ to Europe for more than half a century. Even during the Cold War and the turmoil of the Soviet collapse, the flow of Russian oil and gas never stopped. But now, Russia seems to have decided to abandon such precious trust and its status built over years by breaking existing contracts, actively creating turmoil in the oil and gas market, and driving up prices by controlling gas export volumes.

[Figure 5] Russia’s Tree Biggest Potentials for Realizing Decarbonization

Under these new circumstances, there are several points that we should pay attention to in relations with Russia to re-evaluate and review its energy strategy and security.

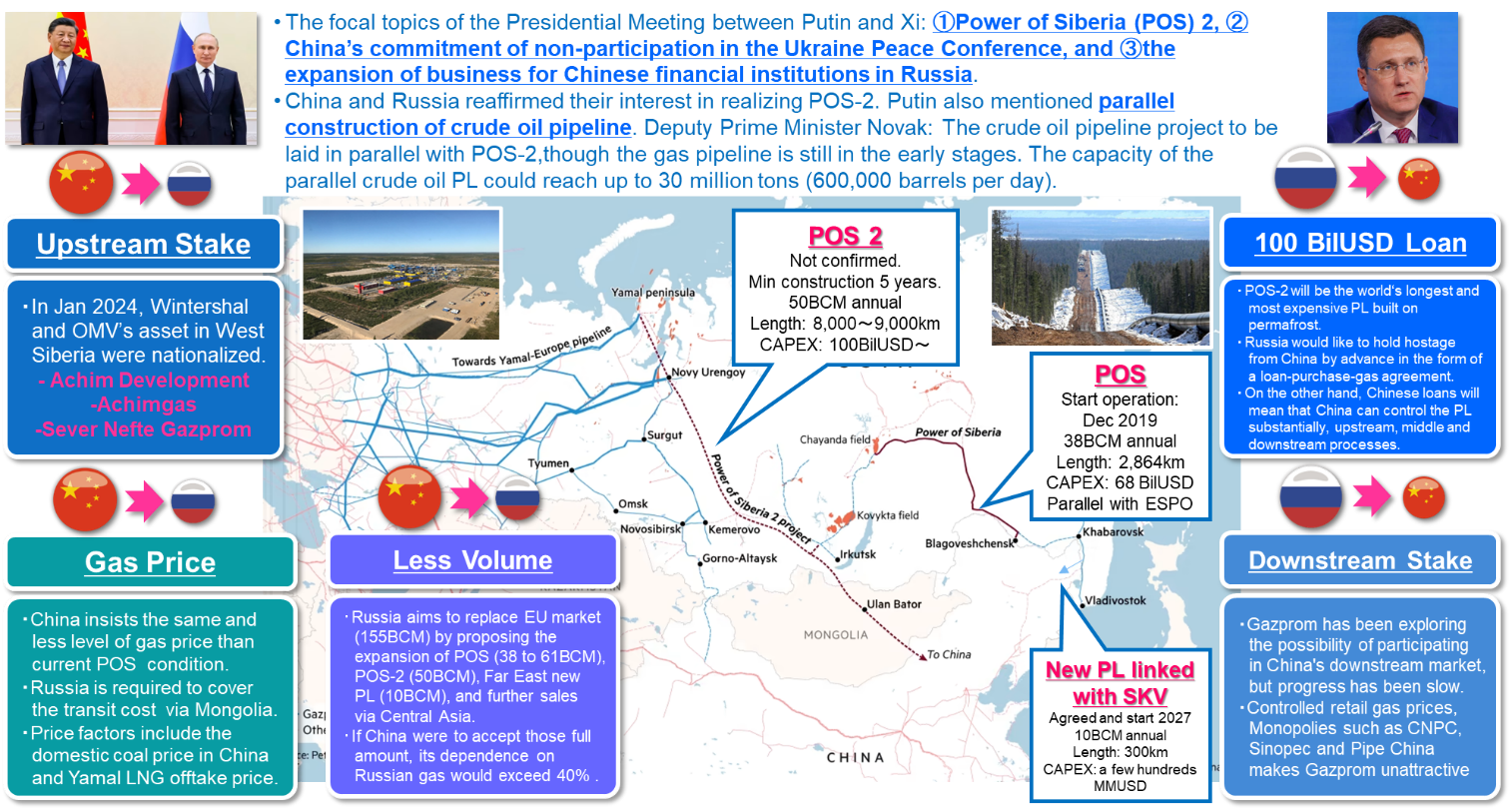

First of all, we must understand the crucial change; Russia is no longer what it used to be. This means that Russia has ceased to be a reliable partner that emphasizes economic relations and adheres to international commercial practices, which was the tacit premise for deepening Japan-Russia cooperative relations. Forced ruble payments to Europe for violating existing contracts (March 2022), suspension of Nord Stream supply (June-August 2022), and mandatory transfer of the stakes and rights of each Sakhalin 1 and 2 project to Russian entity (June-August 2022) have decisively discredited Russia. Second, it is inevitable that Russia’s energy income will shrink as a result of Europe’s accelerated leave from Russia in the long term. Russia has already been forced to provide cheap energy to the Chinese market: oil from 2010 and gas from 2019. And it will be accelerated by its losing of the European market now. Power of Siberia 2 would be the coming symbol of Russia-Sino energy cooperation, but this pipeline can be realized only by Russia’s discount of gas price for China, as it was done in Power of Siberia, which was agreed in 2014 (started operation in 2019). This trend will most probably not be short-term and likely be prolonged in conjunction with the situation of Ukraine Crisis and its post-war process. In other words, it is expected that Russia will no longer be a major power that enjoyed economic revival by the soaring crude oil prices in the early 21st century. Its energy income that was the driving force for the economy will be cut off over the long term, weakening power of the state.

[Figure 6] Ongoing Negotiation on Power of Siberia (POS)

With those perspectives, it is necessary to consider how the bilateral and trilateral relationship with Russia will change and whether it can be rebuilt from a long-term period. What kind of changes in the balance of power will a weakening Russia bring about in Northeast Asia? What opportunities does Japan and Korea can maximize its national interests amid changes with weakening Russia?

Both Japan and Korea have declared to achieve the Carbon Neutrality toward 2050. There is an urgent need to secure natural gas supply as the transition energy for coal and oil, moreover as the source of hydrogen as a new energy. Also, CCUS has potential, along with the utilization of forest sinks. Russia has the world’s largest assets in those areas, and their importance for the rest of the world will increase in the next decades. We must consider how Japan and Korea can utilize these assets owned by Russia while its national power weakens in long term.

III. How to Be on the Winning Team in the Decarbonization Game: Potential Cooperations between Japan and Korea

1. Decarbonization Technology Innovation

The winners and losers in this game are clear, and it is directly linked to whether or not energy security can be strengthened. In other words, the winners are those who sell low-carbon energy and technology for production and manufacturing, which are the core of realizing decarbonization, and those who are on the buying side will be losers.

In this grand game, Japan and Korea, as major energy consumers without abundant indigenous resources, are in a position of the buying side. On the other hand, both countries hold the key for the development of decarbonization technologies that both countries’ high-tech companies already have. Japan, followed by Korea and Germany, has the highest GX-related patent score. In this field, Japan and Korea have already taken a pole position for the race.

Furthermore, technological innovation might significantly redraw the current map of energy between producing and consuming countries. Combination of electricity from renewable energies with Direct Air Capture (DAC) technology may even trigger the possibility for Japan and Korea to become fuel producing (manufacturing) countries. At present, it is not competitive with conventional fuels derived from fossil fuels, and it cannot be a business unless it relies on government subsidies and carbon credits. However, if the cost of electricity from renewable energy sources and DAC technology decreases gradually by incessant efforts and innovations, both countries may emerge as new fuel and oil producing countries.

2. Promotion of Continuous Investment for Upstream, Especially LNG

It is natural that the path towards decarbonization differs from country to country, and the greatest concern is that the time-bound goal of achieving decarbonization will take precedence, with emphasis placed solely on meeting that deadline. Continued upstream investment for the world energy demand including fossil fuels for transition is essential to meet the sufficient supply of energy that humanity still needs, and we must not forget that current divestment will manifest itself in the form of tight supply and demand due to reduced production and the associated rise in market prices over the medium to long term from now on.

3. Coalition for LNG Emission Abatement toward Net-zero (CLAEN)

Methane, one of the greenhouse gases (GHG), is a major component of LNG and 28 times higher greenhouse effect than CO2. It is emitted from the value chain including the production process of LNG. Accelerating methane mitigation is a critical global challenge. In order to reduce methane emissions, the Coalition for LNG Emission Abatement toward Net-zero (CLEAN) was announced in LNG PCC 2023. It is an initiative launched by JERA, KOGAS and JOGMEC. CLEAN stresses the importance of enhancing transparency for methane emissions associated with the LNG value chain and sharing best practices. It aims to make the LNG value chain cleaner by allowing major LNG buyers in Japan and Korea to talk to LNG producers regarding reducing methane emissions. It is expected that this framework will be extended to involve other private companies in the future all over the world.

4. Creating and Nurturing Markets for H2 from LNG Practice

Japan and Korea also have long experience and knowledge in LNG market development history. Best practices in LNG industry such as upstream, middle-stream, downstream, SPA contracts, and establishment of new market with accountability and transparency will be required in the beginning of merging H2 and Ammonia market. Taking the initiative and contributions through rules making in this field by Japan and Korea might benefit both countries’ energy security. ■

References

Agency for Natural Resources and Energy (ANRE-METI). 2018. “Strategic Energy Plan (in Japanese).” July 3. https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/category/others/basic_plan/past.html.

ANRE-METI. 2022. “Here’s more about the 6th Strategic Energy Plan Efforts to overcome ‘grid constraints’ toward expanding the introduction of renewable energy.” April 28. https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/en/category/special/article/detail_174.html.

Presidential Office of Russian Federation. 2021. “Leaders Summit on Climate.” April 22. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/65425.

Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI). 2024. “The 67th meeting of the General Resources and Energy Investigation Council, Basic Policy Subcommittee (In Japanese).” December 17. https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/committee/council/basic_policy_subcommittee/2024/067/.

The Korea Times. 2024. “Korea to Increase the Proportion of Nuclear Power.” October 10. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/tech/2023/01/419_343496.html#:~:text=Korea%20will%20increase%20the%20proportion%20of%20nuclear%20power,to%20below%2015%20percent%20and%2010%20percent%2C%20respectively.

■ Daisuke Harada is Project Director of the Research and Analysis Department at the Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security (JOGMEC).

■ Typeset by Chaerin Kim, Research Assistant

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | crkim@eai.or.kr

Center for Japan Studies

Korea-Japan Future Dialogue

![[ADRN Working Paper] Democratic Backsliding in South Korea](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250702151055558995988(0).jpg)

Working Paper

[ADRN Working Paper] Democratic Backsliding in South Korea

Asia Democracy Research Network | 2025-03-14

![[ADRN Working Paper] The Impact of the Millennials and Gen Z on Democracy in Northeast Asia](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/202505231731371005535793(0).jpg)

Working Paper

[ADRN Working Paper] The Impact of the Millennials and Gen Z on Democracy in Northeast Asia

Asia Democracy Research Network | 2025-03-14