![[ADRN Issue Briefing] The Struggle Against Disinformation: Dissecting the Ecosystеm](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20250604161933930489037.jpg)

[ADRN Issue Briefing] The Struggle Against Disinformation: Dissecting the Ecosystеm

| Commentary·Issue Briefing | 2025-06-04

Sunghack Lim

Professor, University of Seoul

Sunghack Lim, Professor at the University of Seoul, examines the growing threat of disinformation across Asian countries, especially in light of the increasing use of social media, political manipulation, and foreign electoral interference. Lim highlights the accelerating proliferation of false narratives in the form of deepfakes and algorithm-driven campaigns, which are undermining electoral integrity. He underscores the pressing necessity to strengthen media literacy and develop balanced responses that curb disinformation without compromising digital freedoms.

※ This issue briefing is an excerpt of Asia Democracy Network’s report entitled “The 2024 Democracy Overview” published on May 19, 2025.

Disinformation is becoming an increasingly significant challenge in Asia, with its prevalence expected to intensify in the coming years. This trend is driven by several key factors that contribute to the region’s vulnerability to disinformation and its spread.

First, Asia continues to have a large population of social media users, many of whom operate within closed networks due to privacy concerns, the desire to connect with like-minded users, and other information security considerations. This ecosystеm remains particularly susceptible to the rapid dissemination of disinformation, as information tends to circulate within echo chambers with limited external fact-checking.

Second, the political exploitation of disinformation has been a persistent issue in many Asian countries, with a notable escalation during election periods. Asian countries are especially vulnerable given persistent issues on weak electoral admіnistration and campaign regulations. This pattern is expected to persist and potentially worsen in Asian nations scheduled for elections in 2025 given growing political divides and instability the region is experiencing. Furthermore, foreign electoral interference on social media discourses, particularly from actors such as China and Russia, continues to be a concern as these nations leverage disinformation to advance their geopolitical interests.

Third, the emergence of AI-powered disinformation campaigns in Asia presents a worrying trend. The sophisticated use of artificial intelligence in creating and spreading false narratives poses new challenges to information integrity and democratic processes.

Last, the generally low levels of media literacy among Asian populations exacerbate the issue. Many citizens lack the critical skills necessary to differentiate between reliable information and disinformation, making them more susceptible to manipulation.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge that the rapid proliferation of social media and advancements in AI technology across Asia have also yielded positive outcomes, such as enhanced information accessibility and increased civic engagement. This presents a complex dilemma: stringent regulations aimed at curbing disinformation might inadvertently suppress these beneficial aspects of digital communication. Consequently, finding an effective solution that balances the mitigation of disinformation with the preservation of digital freedoms remains a significant challenge.

Disinformation’s Fertile Ecosystеm

The widespread adoption of social media platforms has led to exceptionally high usage rates of platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp across most Asian countries. A recent study evaluating internet usage in Southeast Asia revealed that adolescents aged 16-24 spend an average of 10 hours per day online (Kemp 2021). This extensive engagement with digital platforms significantly amplifies the risk of exposure to disinformation in the region. In 2023, the Asia-Pacific region accounted for approximately 60% of the global social media user base. With a steady annual growth rate of 2.7%, this region was projected to add over 59 million new users in 2024, surpassing the combined global user growth. The trend of increasing social media subscriptions and usage time is expected to continue into 2025, further exacerbating the potential for disinformation spread (DMFA 2025).

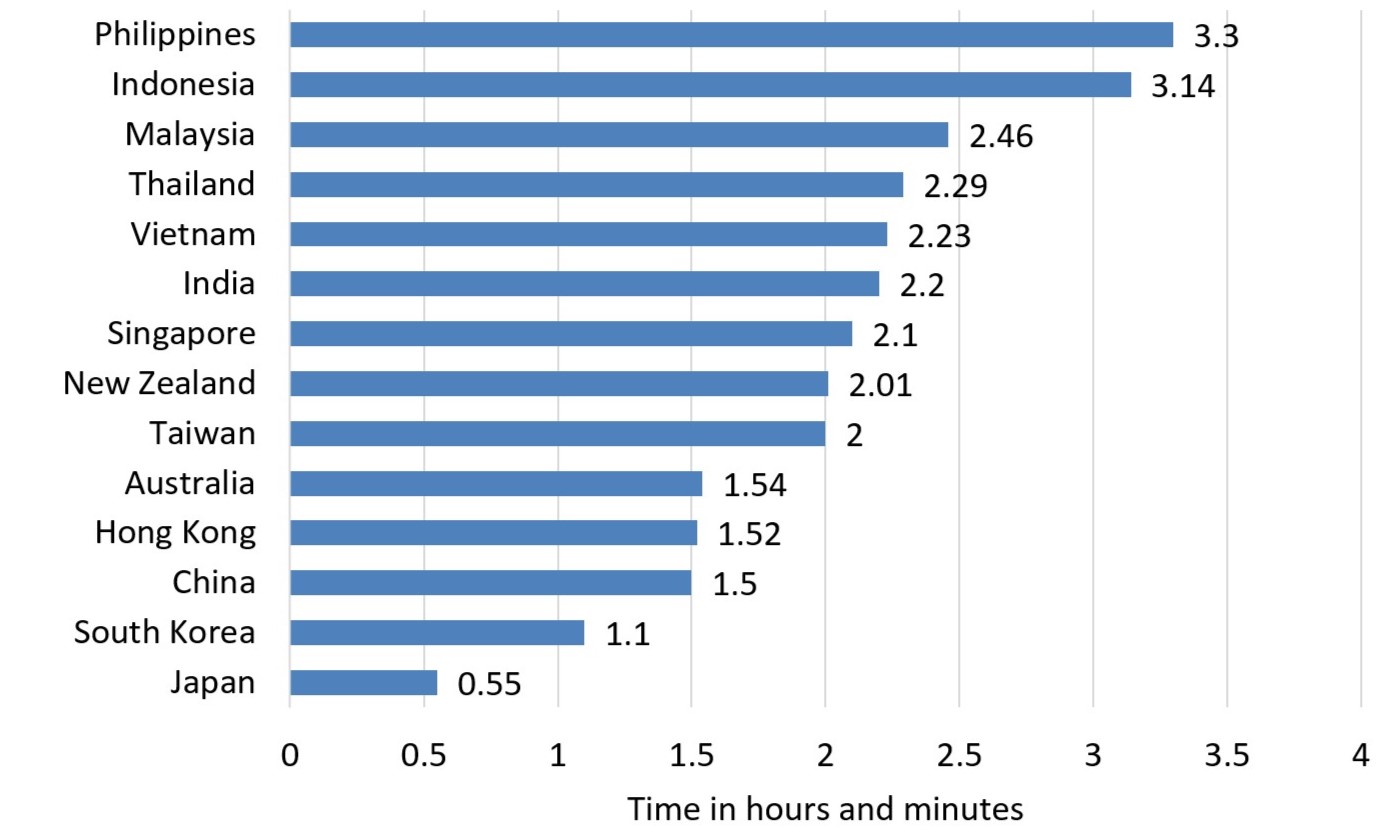

According to DataReportal’s survey of internet users aged 14-64 in the Asia-Pacific region during the fourth quarter of 2023, significant variations in social media usage patterns were observed across different countries (Figure 1). The study, which examined the average daily time spent on social media platforms, revealed that the Philippines led the region in social media engagement. Internet users in the Philippines demonstrated the highest average daily social media usage, spending three hours and 30 minutes per day on these platforms. This finding underscores the substantial role that social media plays in the daily lives of Filipino internet users. Following the Philippines, Indonesia emerged as the second most active country in terms of social media usage. Malaysia and Thailand also exhibited notable levels of engagement, ranking third and fourth respectively in the survey (Statista 2023). The data suggests that social media has become deeply embedded in the daily routines of internet users in these countries, potentially influencing various aspects of social interaction, information dissemination, and consumer behavior.

Figure 1. Average daily time spent using social media in the Asia-Pacific region in the 4th quarter of 2023, by country or territory (in hours and minutes)

Beyond the issues of subscriber numbers and usage time, the network structure of social media platforms presents an additional challenge. Popular social media and messaging apps in Asia such as Facebook, Tiktok, WhatsApp and X (formerly Twitter) predominantly feature closed networks known as “walled gardens.” Information disseminated through these networks tends to resonate strongly, as recipients place greater trust in groups sharing similar perspectives. These “walled gardens” are characterized by restricted user groups, where users primarily connect with individuals holding similar viewpoints. This structure facilitates trust-based information sharing, leading users to place higher confidence in information circulated within their intimate networks. Consequently, this closed network structure creates an environment conducive to the rapid spread of fake news, allowing it to gain credibility without proper verification, thereby increasing vulnerability to the proliferation of false information (Yee 2017). For instance, in the Philippines, disinformation spread by supporters of President Rodrigo Duterte through Facebook pages and groups have been instrumental in shoring up support for the admіnistration’s bloody “war on drugs.”

The Proliferation of Political Disinformation and Foreign Electoral Interference

Political disinformation has emerged as a paramount concern in numerous countries, with its prevalence particularly acute during electoral periods (Kajimoto and Stanley 2018). The extensive utilization of social media platforms by politicians for voter engagement and campaign purposes has led to a significant surge in disinformation targeting sensitive issues such as religion and ethnicity during election seasons. Organized dissemination of false information by cybertroopers has been documented (Iannone 2022). Various political actors and parties have employed digital campaign specialists and engaged entities such as ‘buzzers’ (Indonesia), ‘trolls (Philippines), and ‘IO’ (information operators, Thailand) to propagate manipulated narratives aimed at discrediting political opponents. Some politicians have resorted to exacerbating religious (Indonesia/Thailand) and ethnic tensions (all three countries) within communities in desperate attempts to secure votes. Concurrently, technology platforms, journalists, and fact-checkers are struggling to keep pace with the sophisticated innovations of disinformation architects. Notably, state actors and government legislators in these countries have been implicated not only in failing to mitigate disinformation but also in directly producing political falsehoods. This involvement of official entities in the creation and spread of disinformation presents a significant challenge to information integrity and democratic processes in the region.

Elections in Asia have transcended domestic concerns, evolving into a matter of international significance. Recent evidence has revealed that nations such as Russia, China, and Iran are actively intervening in foreign electoral processes to advance their own geopolitical interests through various means, as a response to the West’s pivot to Asia, and in an effort to assist local allies more sympathetic to their cause. Among these, the dissemination of disinformation has emerged as the most prevalent form of foreign electoral interference. The content of this disinformation is strategically crafted to exacerbate existing societal tensions, targeting fault lines along racial, class, religious, and generational divides. This deliberate amplification of polarization poses a significant threat to democratic institutions and processes. Foreign electoral interference, particularly through disinformation campaigns, represents a complex challenge to the integrity of democratic systеms. These interventions exploit the vulnerabilities inherent in open societies, leveraging digital platforms and social media algorithms to maximize their impact.

According to Wang Chan-Hsi of the Institute for National Defense and Security Research, China’s influence operations are increasingly leveraging algorithms on social media platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, and TikTok to disseminate a high volume of short videos laden with messaging favorable to the Chinese Communist Party. Researchers from Princeton University have found that this content is finely calibrated to target specific demographics, including elderly voters who may be more susceptible to misinformation and younger viewers whose political identities are not yet fully formed. These sophisticated tactics exploit the algorithmic curation of content on social media platforms, which may exacerbate political polarization by amplifying content consistent with users’ existing beliefs while suppressing contradictory information (McCartney 2024).

AI-driven Disinformation

OpenAI’s recent disclosure of five covert influence campaigns utilizing its artificial intelligence (AI) technologies for deceptive manipulation of public opinion worldwide has brought to light the growing concern over AI’s role in disseminating disinformation, particularly during election periods (Metz 2024). This revelation underscores the potential for AI-generated misinformation to significantly impact voter trust, distort perceptions of candidates and issues, and potentially manipulate electoral outcomes. The increasing sophistication of AI tools has facilitated the production of fake news, deepfakes, and misleading narratives with unprecedented ease. Globally, there has been a 245% year-on-year increase in deepfake incidents, with some Asian-Pacific countries experiencing even more dramatic surges: South Korea (1625%), Indonesia (1550%), and India (280%). This trend is particularly alarming given the numerous elections scheduled for 2024 and 2025 across various nations. Indonesia’s recent experience exemplifies the challenges posed by AI-generated misinformation in electoral contexts (Ng 2024).

Deepfake videos featuring presidential candidate Anies Baswedan speaking fluent Arabic and the late president Suharto endorsing a Golkar Party candidate garnered millions of views. The Indonesian Anti-Defamation Society reported a doubling of AI-related disinformation compared to previous elections (Beltran 2024). The rise of AI presents a complex dilemma for democracies across Asia. Governments and politicians from the Philippines to South Korea are grappling with AI’s dual potential: its capacity to improve voter engagement, streamline campaigns, and enhance election admіnistration, juxtaposed against its ability to propagate misinformation and potentially undermine the integrity of democratic processes.

The Critical Role of Media Literacy in Combating Disinformation

In the contemporary digital landscape, the proliferation of disinformation poses a significant threat to democratic processes and social stability. To effectively address this challenge, the development of robust media literacy capabilities among citizens is paramount. Media literacy, defined as the ability to critically analyze, evaluate, and create media content, serves as a crucial defense mechanism against the spread of false or misleading information.

The importance of media literacy is particularly pronounced in Asian countries, where the rapid digitalization of information ecosystеms has outpaced the development of critical media consumption skills among the general population.

The OECD’s 2021 report “21st-Century Readers: Developing Literacy Skills in a Digital World” provides valuable insights into the media literacy capabilities of students across different countries. This study, released in May 2021, offers a comprehensive assessment of 15-year-old students’ ability to navigate and evaluate digital information, with a particular focus on their capacity to distinguish between facts and opinions. The results of this assessment revealed significant disparities in digital literacy skills among OECD member countries. Notably, South Korean students, despite their generally high performance in reading skills, demonstrated a surprisingly low proficiency in distinguishing facts from opinions. Only 25.6% of Korean students successfully identified factual information from opinions, a figure substantially below the OECD average of 47% (OECD 2021).

To address these challenges, a concerted effort to enhance media literacy education across Asia is imperative. This endeavor should encompass formal education systеms, from primary schools to universities, as well as adult education programs and public awareness campaigns. Curriculum development should focus on critical thinking skills, digital literacy, and the ability to verify information sources (EDUtechtalks 2024). Governments and civil society are taking various measures, including legislation, fact-checking, and media literacy education. However, effective measures have been hampered by concerns about infringements on freedom of expression (Kajimoto and Stanley 2018). ■

References

Beltran, Sam. 2024. “Will AI Enhance or Undermine Asia’s Elections?” South China Morning Post. December 15. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3290710/will-ai-enhance-or-undermine-asias-elections (Accessed December 20, 2024)

Digital Marketing for Asia: DMFA. 2024. “Most Popular Platforms Social Media in APAC in 2025.” https://www.digitalmarketingforasia.com/most-popular-platforms-social-media-in-apac-in-2025/ (Accessed December 20, 2024)

EDUtechtalks. 2024. “Strengthening Media Literacy in Southeast Asia: A Collaborative Effort led by USAID.” February 2. https://edutechtalks.com/strengthening-media-literacy-in-southeast-asia-a-collaborative-effort-led-by-usaid/ (Accessed December 20, 2024)

Kajimoto, Masato, and Samantha Stanley. 2018. Information Disorder in Asia. The Journalism & Media Studies Centre. 1-53.

McCartney, Micah. 2024. “China’s Election Interference in Taiwan Explained.” Newsweek. January 4. https://www.newsweek.com/china-election-interference-taiwan-2024-presidential-legislative-elections-1857622 (Accessed December 20, 2024)

Metz, Cade. 2024. “OpenAI Says Russia and China Used Its A.I. in Covert Campaigns.” New York Times. May 30. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/30/technology/openai-influence-campaigns-report.html (Accessed December 20, 2024)

Ng, Victor. 2024. “Combating deepfake fraud during elections.” CybersecAsia. https://cybersecasia.net/features/combating-deepfake-fraud-during-elections/ (Accessed December 20, 2024)

OECD. 2021. 21st-Century Readers: Developing Literacy Skills in a Digital World. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/21st-century-readers_a83d84cb-en.html (Accessed December 20, 2024)

Statista. 2023. “Average daily time spent using social media in the Asia-Pacific region as of 3rd quarter 2024, by country or territory.” https://www.statista.com/statistics/1128147/apac-daily-time-spent-using-social-media-by-country-or-region/ (Accessed December 20, 2024)

Yee, Andy. 2017. “Post-Truth Politics Fake News in Asia.” Global Asia 12, 2: 67–71.

■ Sunghack Lim is a Professor of International Relations at the University of Seoul.

■ Edited by Hansu Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | hspark@eai.or.kr

Center for Democracy Cooperation

Asia

Democracy

Democracy Cooperation

Asia Democracy Research Network

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] India`s State of Emergency at 50: Enduring Lessons for Democracy](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/202507238542964953507(0).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] India`s State of Emergency at 50: Enduring Lessons for Democracy

Niranjan Sahoo | 2025-06-04