![[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability in the Case of South Korea (Interim Report)](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250403182747822722199.jpg)

[ADRN Working Paper] Vertical Accountability in the Case of South Korea (Interim Report)

Working Paper | 2024-08-23

Sunkyoung Park

Professor in the Division of Global Korean Studies, Korea University

Sunkyoung Park, Professor at Korea University, examines the mechanisms of vertical accountability in South Korea, emphasizing the alignment between formal institutions and their actual performance. Park’s analysis reveals that South Korea’s electoral accountability mechanism functions effectively, with no significant discrepancies between legal frameworks and practical outcomes. However, the study identifies areas for improvement in the democratic process, such as addressing scandals involving the intelligence service’s attempts to manipulate public opinion and the electoral management body’s susceptibility to political pressure.

1. Introduction

To what extent do political institutions in South Korea meet the democratic norm of vertical accountability? Do they actually demonstrate accountability to voters? If the de jure institutions of vertical accountability do not align with the de facto performance of such accountability, where are the discrepancies? Despite the theoretical and practical importance of accountability in the political systеm, few studies have provided empirical evidence on both the de jure institutions of vertical accountability and their de facto performance.

To address this gap, this project examines the de jure institutions of vertical accountability and the de facto performance of vertical accountability in South Korea. Specifically, the study addresses four research questions: (1) Which constitutional and legal mechanisms hold the Korean government accountable? (de jure accountability) (2) To what extent do these accountability mechanisms function effectively? (de facto accountability) (3) Are there discrepancies between the de jure and de facto accountability? (4) What short-term remedies and long-term reforms could address these discrepancies? As a first step toward answering these questions, this memo reviews electoral accountability in South Korea.

In terms of methodology, this memo employs mixed methods. A review of de jure accountability is based on articles and chapters of the constitution and relevant laws.[1] To evaluate de facto accountability, I use Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) data from 1980 to 2022. Cross-national comparisons will also be conducted to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the Korean case. The mean performance of three sets of countries is used as a comparison: (1) OECD countries, (2) ADRN participants, and (3) 18 third-wave democracies: Indonesia, Mongolia, the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. These 18 cases consist of the six largest third-wave democracies in each region. The selection criterion follows Kim (2022).

The structure of this memo is as follows. The next chapter defines vertical accountability and describes its subtypes, domains, and the items used to assess each. Chapter 3 reviews de jure and de facto electoral accountability in Korea, while Chapter 4 discusses diagonal accountability. The concluding chapter discusses short-term remedies and long-term reforms that could mitigate the discrepancies between de jure and de facto accountability in South Korea.

2. Definitions and Subtypes of Vertical Accountability

As accountability is at the center of democratic governance and policymaking, numerous studies have defined accountability and its subtypes. For example, Luhrmann et al. (2020) define accountability as “de facto constraints on the governments use of political power through requirements for justification of its actions and potential sanctions” (Luhrmann et al. 2020, 811). Subtypes of accountability are organized according to the spatial relationship between the government and voters, bodies within the government, and the government and civil society. Firstly, the accountability between the government and voters is referred to as vertical accountability or electoral accountability. Schedler and colleagues define it as “the ability of a state’s population to hold its government accountable through elections and political parties” (Schedler et al. 1999). Thus, the level of electoral accountability is contingent upon the quality of elections and political parties.

The second subtype is horizontal accountability, where state institutions hold the executive branch of the government accountable. This type of accountability consists of the checks and balances between the executive body and the legislative body, as well as judicial oversight of the executive body. This may include demands for information and punishment of improper behavior (O’Donnell 1998; Rose-Ackerman 1996).

The third subtype is diagonal accountability, in which civil society holds the government accountable, for example, by providing information about the government or pressuring it to change its policies (Grimes 2013; Malena and Forster 2004; Peruzzotti and Smulovitz 2006). Electoral accountability describes citizens’ power to hold the government accountable by participating through formal channels such as elections. In contrast, diagonal accountability denotes the ability or power of citizens to hold the government accountable via non-electoral and informal tools.

It should be noted that this memo conceptualizes vertical accountability in a broad manner, encompassing both electoral accountability and diagonal accountability. This is based on the premise that vertical accountability should capture both citizens’ formal and informal avenues through which citizens can hold the government accountable.

Each vertical accountability subtype has several domains. Electoral accountability has two domains: the quality of elections and the quality of political parties. This is because the primary mechanism through which citizens hold the government accountable is by voting. The evaluation of the quality of elections is typically concerned with the eligibility of voters, the ease of the voting process, the fairness and competitiveness of elections, the regularity and peaceful conduct of elections, and the supervision of electoral processes by a capable and autonomous electoral management body. The evaluation of the quality of political parties focuses on party formation and the independence of the opposition from the ruling regime. To evaluate the de jure and de facto characteristics of elections using empirical evidence, items that reflect these two domains are selected from the V-Dem variables, as indicated in Table 1.

The domains of diagonal accountability concentrate on the extent to which citizens can engage in policy-making processes that extend beyond electoral participation. They are evaluated by observing media freedom, civil society organizations (CSOs), freedom of expression, and citizens’ engagement in politics. The items that assess diagonal accountability are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Domains and Items to Assess Vertical Accountability

|

|

Domain |

Item |

|

Electoral Accountability |

Quality of elections |

Voting rights restrictions |

|

Accuracy of the voter registry |

||

|

Free and fair elections |

||

|

Multi-party elections |

||

|

Intentional irregularities |

||

|

Intimidation and harassment |

||

|

Autonomy of the EMB |

||

|

Capacity of the EMB |

||

|

Quality of parties |

Barriers to party formation |

|

|

Independence of the opposition |

||

|

Diagonal Accountability |

Quality of media freedom |

Media censorship |

|

Quality of CSOs |

Citizens’ voluntary participation in CSOs |

|

|

Quality of freedom of expression |

Citizens’ freedom to discuss political issues and the freedom of academic and cultural expression |

|

|

Quality of engagement of citizens in politics |

The width and depth of public deliberations |

3. De Jure and De Facto Electoral Accountability in Korea

3.1. De Jure Quality of Elections

In South Korea, the de jure quality of elections is secured via the Constitution and electoral laws. Firstly, voting rights are the primary measure of election quality, such as whether there are restrictions on voting rights and how accurate the voter registry is. Article 15 of the Public Official Election Act states that all Korean citizens over the age of 18 have equal voting rights. Furthermore, the voter registry is uncomplicated; all Korean citizens over the age of 18 are automatically registered as voters in accordance with Chapter 5 of the Public Official Election Act.

Secondly, the democratic process of elections is well institutionalized in Korea. Multi-party elections are dictated by Article 8 of the Constitution, which states that “the establishment of political parties shall be free, and the plural party systеm shall be guaranteed.” Free and fair elections are also secured by Articles 41 and 67 of the Constitution, which declare free, fair, and direct elections for the legislature and the President, respectively.[2] The Public Official Election Act defines the principles and rules for all elections. The Act’s Article 1 declares that the goal of the law is to make all elections free, fair, and democratic. Article 7 stipulates that candidates and parties should compete fairly and abide by laws.

Any intentional interference with the electoral process is subject to legal sanction. Articles 237 to 239 of the Public Official Election Act delineate the actions deemed to be obstructions to the freedom of elections and prescribe the penalties for such actions.

Thirdly, the quality of elections is determined by the autonomy and capacity of the Electoral Management Body (EMB). To determine the de jure autonomy of the EMB, an evaluation of the regulations pertaining to the appointment of members, term limits, and the protection of the EMB from political pressure must be conducted. The Constitution defines the establishment and purpose of the EMB. Article 114, Paragraph 2 describes the process of appointing nine members to the EMB, three by the President, with three appointments made by the National Assembly, and three by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Their six-year terms are secured under Article 114, Paragraph 3. It is also noteworthy that the members’ terms are protected unless they commit a serious crime.[3] Article 114, Paragraph 6 and Article 115, Paragraph 1 provide a legal basis for enhancing the capacity of the EMB, citing the EMB’s legal authority to establish regulations and issue instructions regarding the admіnistration of elections.[4] Additionally, Article 5 of the Public Official Election Law permits the EMB to request assistance from any government office with priority. This confers additional capacity upon the EMB. The second row of Table 1 provides a summary of the de jure and de facto qualities of elections in Korea.

3.2. De Facto Quality of Elections

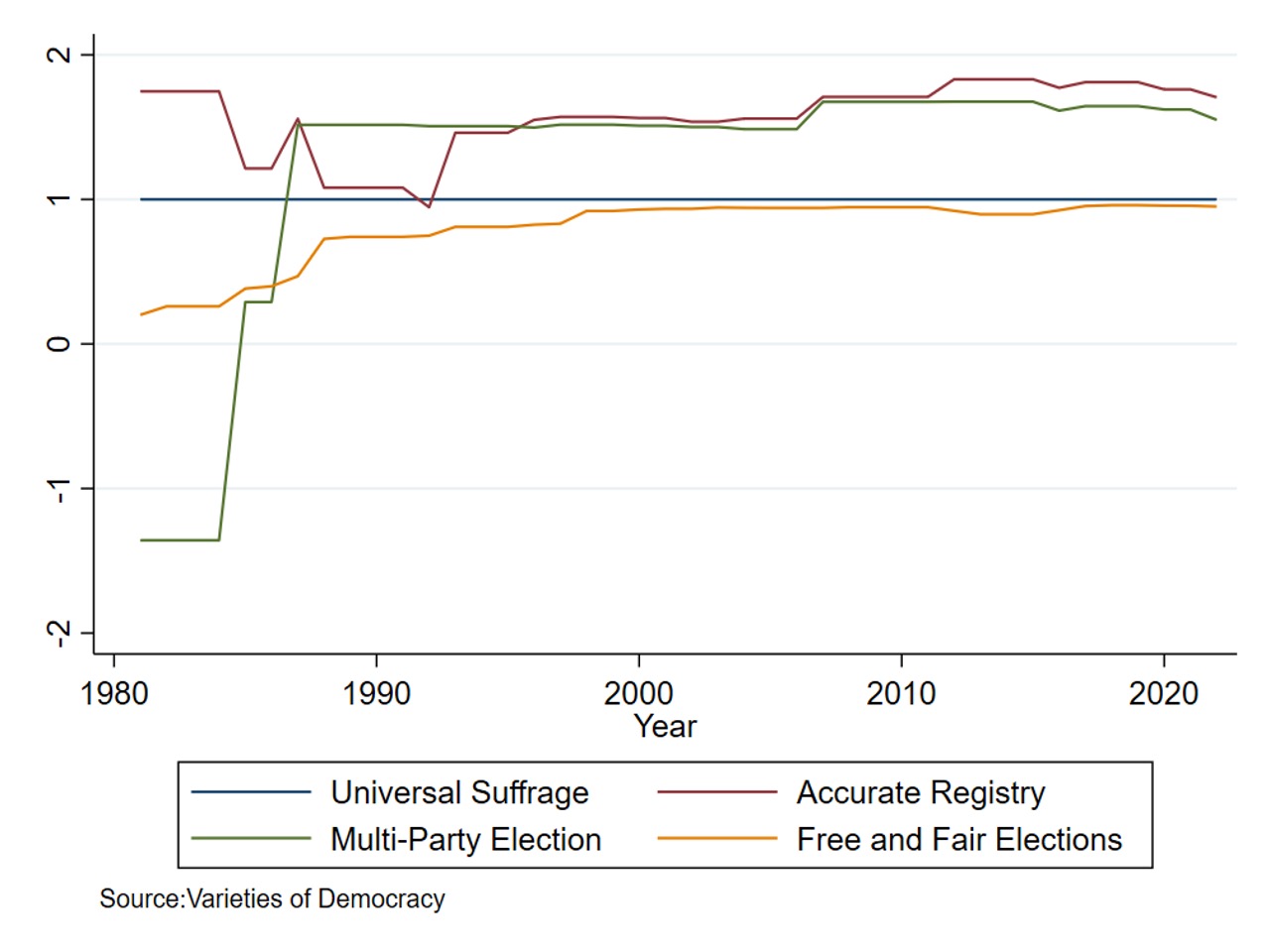

The evaluation of the de facto quality of elections in South Korea is based on eight variables from V-Dem, as illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. The figures show the temporal trajectory of eight variables from 1981 to 2022. Universal suffrage was instituted beginning with the first elections in 1948. Universal adult enrollment on the voter registry is easy and clear. Elections have been conducted in a free and fair manner since the country’s democratization in 1987.

Prior to the 1970s, elections conducted under authoritarian regimes had been competitive, with significant opposition parties. However, the opposition parties became weak after dictator Park Chung-hee’s auto-coup in 1972, which resulted in the dissolution of all parties and the legislature (Kim 2008). A jump in the quality of multi-party elections transpired in 1985, when the 12th legislative elections ended with the unexpected victory of a nascent opposition party. A second jump occurred in 1987, when the inaugural fully democratic presidential elections were held. Since then, South Korea has scored highly on the multi-party election item.

Figure 1. De facto Quality of Elections

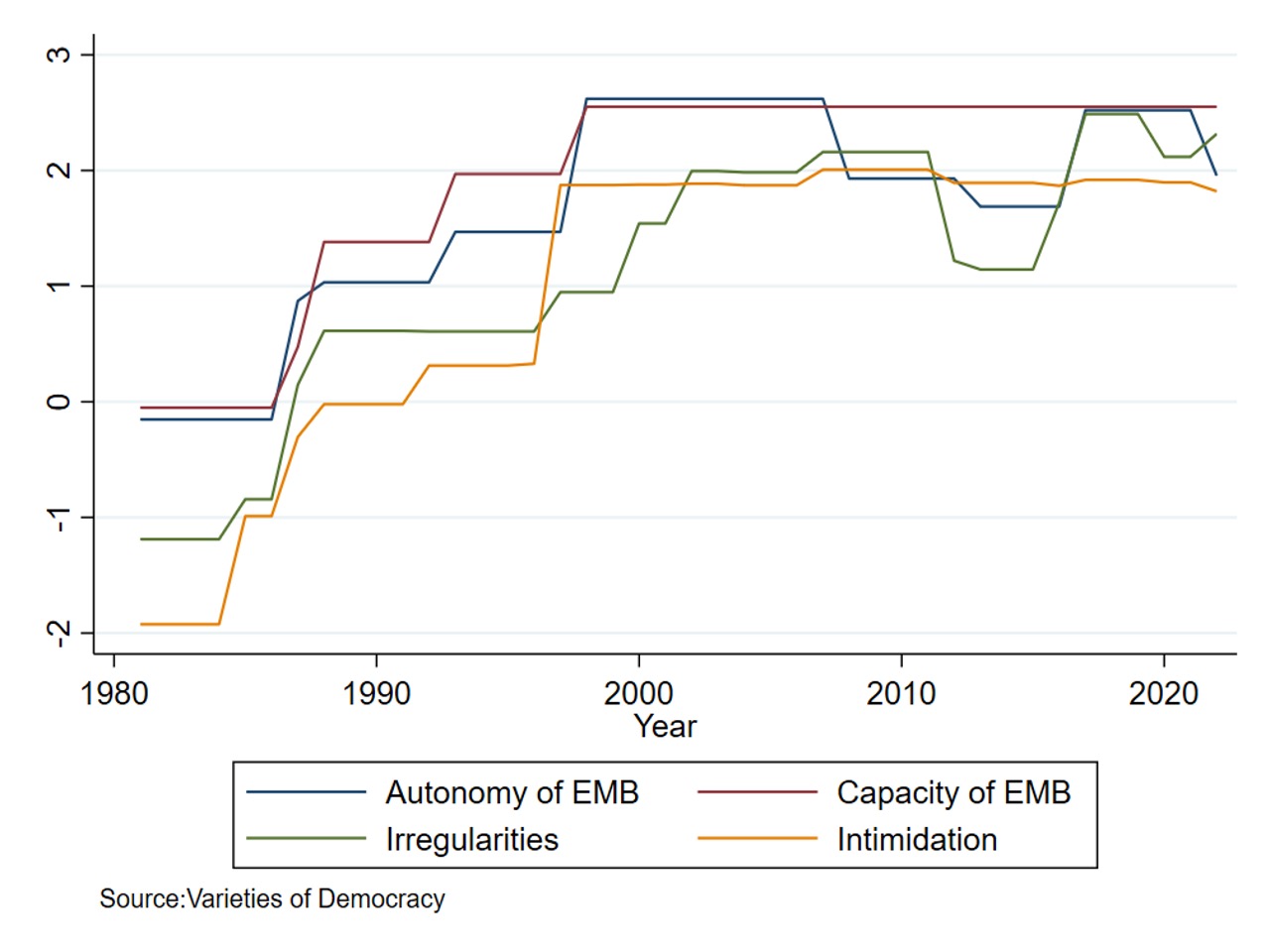

Intentional irregularities are defined as cases where the incumbent and/or opposition parties engage in intentional actions that interrupt the electoral process. These actions may include the use of duplicate IDs, an intentional lack of voting materials, ballot-stuffing, misreporting of votes, or false collation of votes. While some irregularities observed prior to the year 2000, there have been few instances of such occurrences since that time, with a notable exception. The sudden drop in the irregularities score between 2012 and 2015 reflects the National Intelligence Service (NIS) public opinion manipulation scandal. In this scandal, agents of the NIS, working on behalf of then-incumbent presidential candidate Park Geun-hye, engaged in illegal surveillance of some opposition politicians and posted pro-government opinions on social media to sway public opinion.[5]

Intimidation and harassment refer to situations in which opposition parties are subjected to repression, intimidation, violence, or harassment by the government or the ruling party. Such incidents were frequent under the authoritarian regime, but became less frequent following democratization. Since 1996, there have been no documented incidents of intimidation and harassment.

Figure 2. De facto Quality of Elections

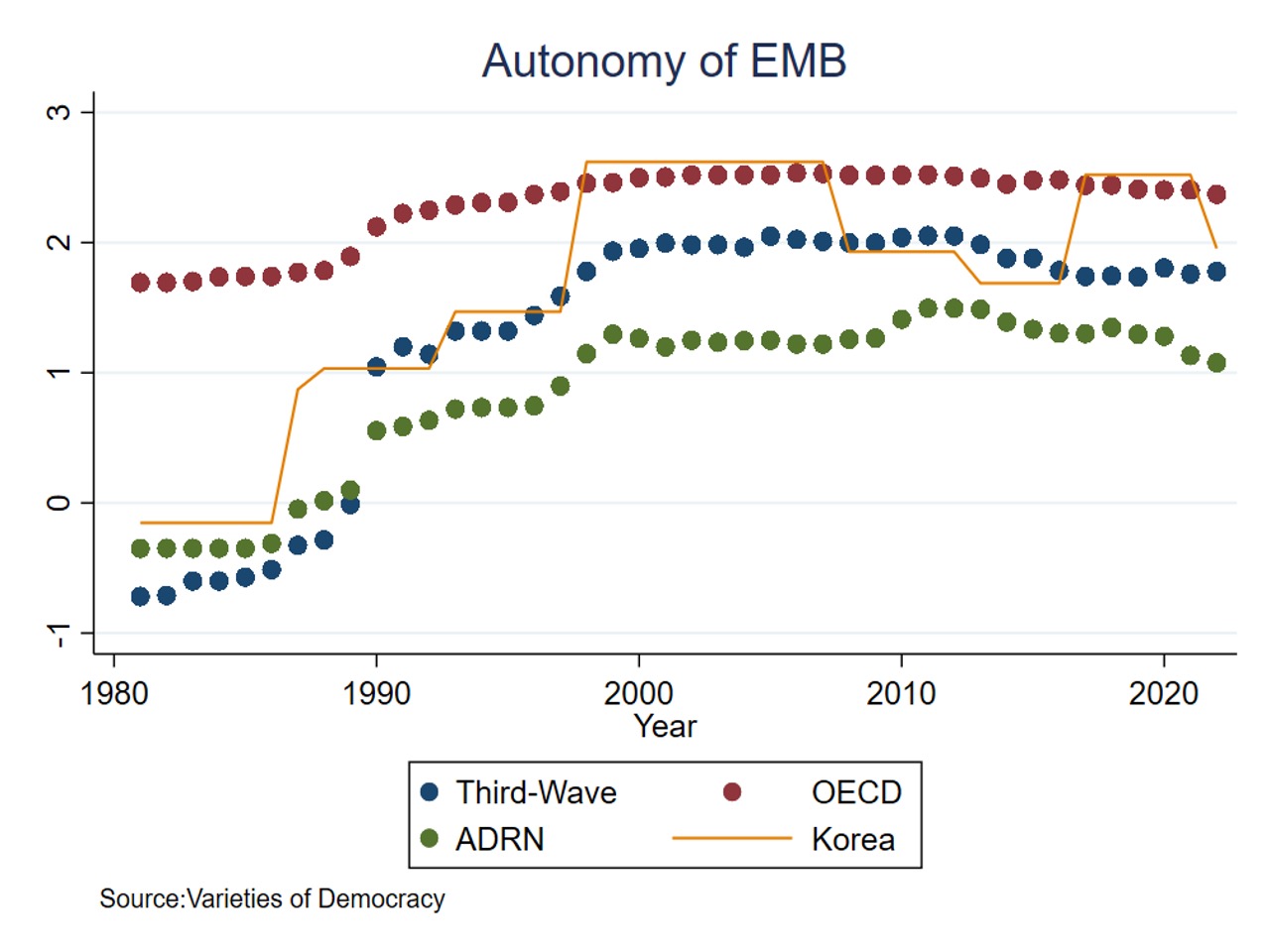

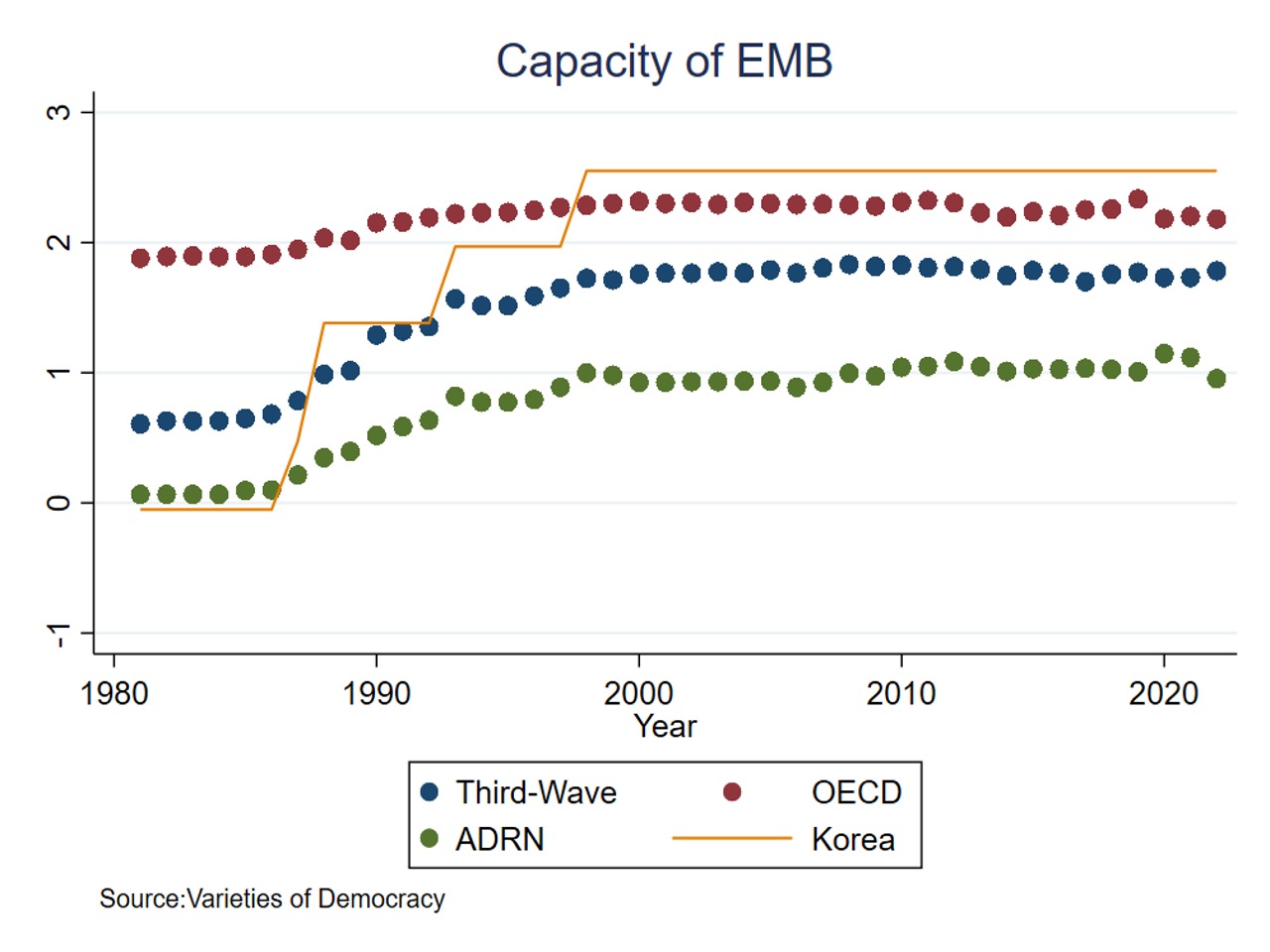

A crucial yet understudied aspect of electoral quality in Korea is the autonomy and capacity of the EMB. Since democratization, the EMB has gradually increased its capacity and autonomy. To evaluate the increase in the capacity and autonomy of the EMB, Figures 3 and 4 present a comparison between the autonomy and capacity of Korea’s EMB with the mean values for third-wave democracies, OECD countries, and ADRN participants, respectively. As a consequence of the democratization occurred in numerous countries during the late 1980s, the level of autonomy increased in third-wave countries and ADRN participants, including South Korea.

Figure 3. Comparison of the Autonomy of EMBs

Figure 4. Comparison of the Capacity of EMBs

An interesting point of increase occurred in 1998. The gradual expansion of the EMB’s legal authority and experience contributed to an increase in its autonomy and capacity. In 1992, a new law was enacted that allowed members of the EMB to issue suspensions or warnings and to request investigations into violations of election laws under Article 14, Paragraph 2 of the Election Commission Act.[6] In 1994, the Public Official Election Act merged several existing electoral laws, thereby reinforcing the EMB’s capacity to oversee the electoral process and to investigate any illicit activities connected with it. In accordance with this legal authority, the EMB assumed responsibility for monitoring all electoral processes, preventing any violations of election law, and punishing illegal election tampering. The National Election Commission (NEC) has on numerous occasions requested that prosecutors file criminal charges using their investigation records regarding election crimes committed by high-ranking politicians, both within the government and in opposition parties.

An analysis by Choi and Cho (2020) posited an additional rationale for the EMB’s elevated degree of autonomy and capacity. In a comparative analysis of 35 countries based on ELECT data from 2016, the South Korean EMB was found to have the fourth largest staff and the second largest budget. The substantial investment in human capital and financial resources would serve to enhance the power of the EMB.

Table 2 provides a summary of the de jure and de facto quality of elections in Korea.

Table 2. De Jure and De Facto Quality of Elections

|

Item |

De Jure Quality |

De Facto Quality |

|

Voting rights restrictions |

Election Act, Article 15 |

No restrictions |

|

Accuracy of the voter registry |

Election Act, Chapter 5 |

Easy and clear |

|

Free and fair elections |

Constitution, Article 8, 41, 67 |

Highly free and fair |

|

Multi-party elections |

Constitution, Article 8 |

Highly competitive |

|

Intentional irregularities |

|

Rarely observed |

|

Intimidation and harassment |

Election Act, Articles 237 to 239 |

Rarely observed |

|

Autonomy of the EMB |

Constitution, Article 114 |

High |

|

Capacity of the EMB |

Constitution, Article 114-115 |

High |

3.3. De Jure Quality of Parties

The quality of parties assesses the independence of the opposition and the existence of any barriers to the formation of political parties. The de jure quality is ensured by Article 8 of the Constitution. Article 8, Paragraph 1 states that the establishment of political parties shall be free, and the plural party systеm shall be guaranteed. Additionally, the Political Parties Act, Chapter VI, provides a legal basis guaranteeing the activities of political parties. The Political Parties Act, Article 37, Paragraph 1 states that political parties shall have freedom in the activities provided for in the Constitution and statutes.

Both the Constitution and the Political Parties Act provide a legal basis for securing the independence of parties by requiring that the government support their activities. Constitution Article 8, Paragraph 3 grants the protection of the State to political parties and also requires government to provide parties with financial support. Such support provides financial independence to opposition parties. The Political Parties Act, Article 37, Paragraph 2 enshrines the freedom of party activities, stipulating that activities such as the recruitment of party members and the promotion of policies and current issues through printed materials, facilities, and advertisements should be guaranteed as normal activities of political parties.[7]

The Constitution does not impose any restrictions on the formation of political parties, except in cases where a party’s actions are deemed to be in violation of the democratic order. Paragraph 4 defines a condition for party dissolution, stating that the Constitutional Court can dissolve a party whose purpose or activities are contrary to the fundamental democratic order.[8]

3.4. De Facto Quality of Parties

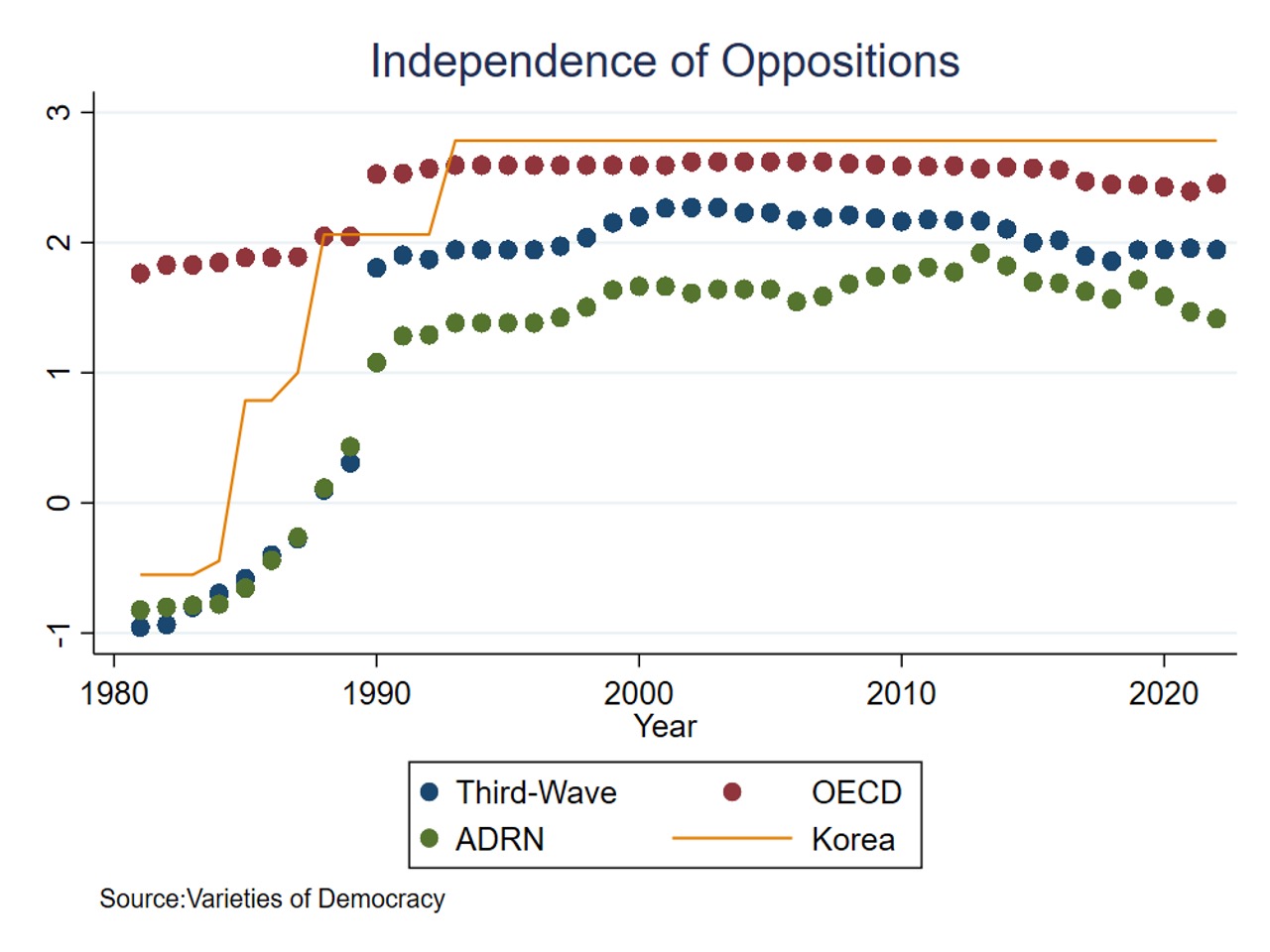

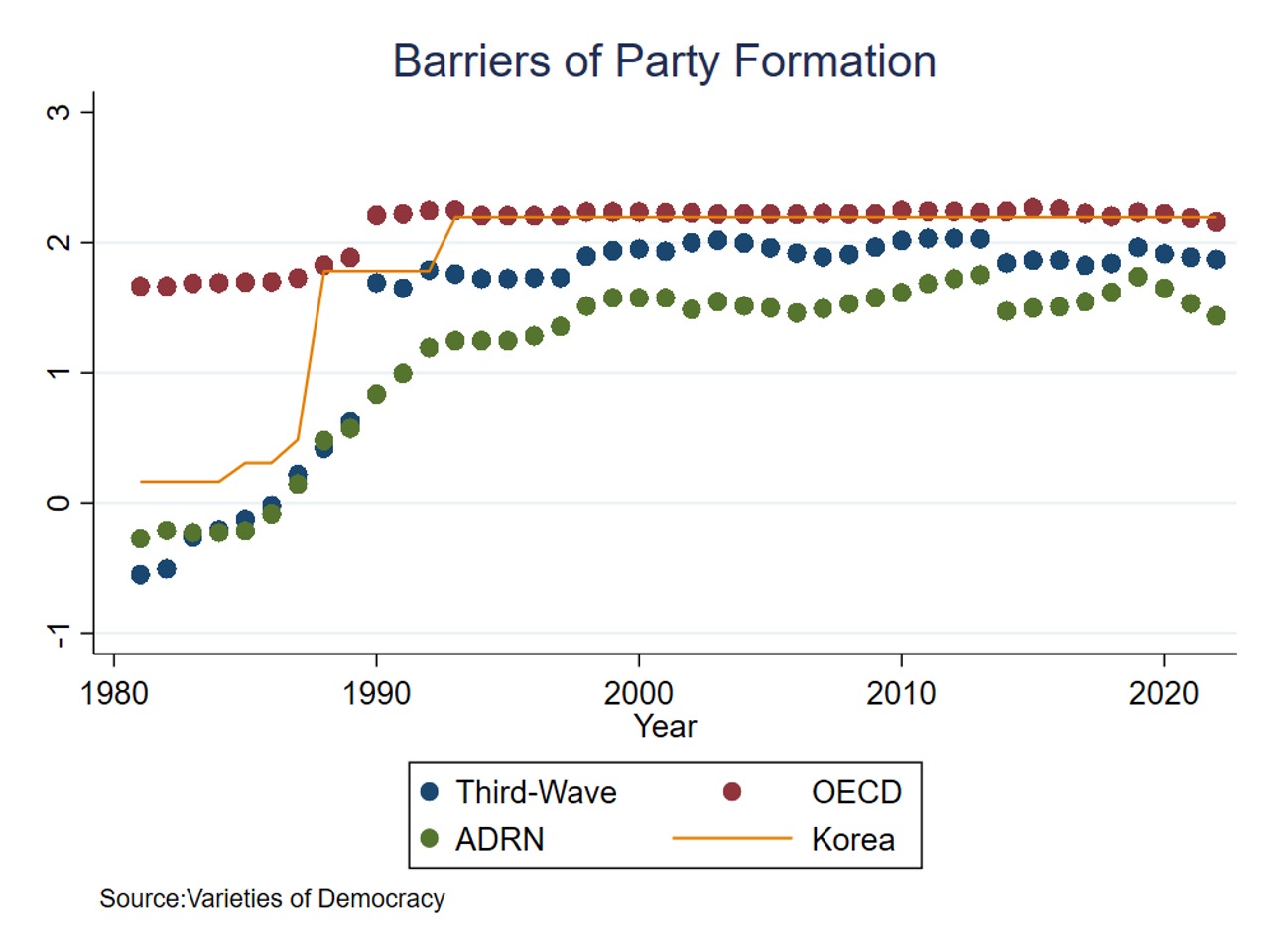

The de facto quality of political parties in Korea can be evaluated using eight variables from V-Dem, as illustrated in Figures 5 and 6. Since the advent of democracy, there has been a notable increase in the autonomy of opposition parties. This has resulted in a relatively stable level of party independence, which is slightly above the mean for OECD countries, as shown in Figure 5. Figure 6 depicts the extent of obstacles to party formation, with higher scores indicating a lack of barriers. Since the country’s transition to democracy, there have been no discernible impediments to the formation of political parties in South Korea. As illustrated in Figure 6, the country’s score for this variable is in close alignment with the mean among OECD countries.

Figure 5. Comparison of the Independence of Opposition Parties

Figure 6. Comparison of Barriers to Party Formation

Table 3 provides a summary of the de jure and de facto quality of parties. With regard to the independence of opposition parties and the question of party formation, it can be concluded that there is no threat to vertical accountability in Korea based on the quality of the parties in question.

Table 3. De Jure and De Facto Quality of Parties

|

Item |

De Jure Quality |

De Facto Quality |

|

Barriers to party formation |

Constitution Article 8, Paragraph 4 |

No restrictions |

|

Independence of the opposition |

Constitution Article 8, Paragraphs 1 and 3, The Political Parties Act Article 37, Paragraphs 1 and 2 |

Very independent |

4. Concluding Remarks

The objective of this project is to address the following subjects regarding the constitutional and legal mechanisms of vertical accountability in South Korea: the de facto performance of accountability, any discrepancies between the de jure and de facto accountability, and solutions that could resolve such discrepancies. As the first step to achieve this objective, this memo has initially examined the de jure institutions of electoral accountability and the de facto performance of electoral accountability in South Korea. The de jure institutions of electoral accountability are well-designed and secured by the Constitution and relevant legislation, including the Election Act and the Political Parties Act. Furthermore, the de facto performance of electoral accountability in South Korea is comparable to or exceeds the mean values observed among OECD countries. In certain instances, South Korea’s performance surpasses the mean values observed among third-wave democracies and ADRN countries. No evident discrepancies are observed between the de jure and de facto dimensions of accountability in Korea. With respect to electoral accountability, the democratic systеm in Korea is functioning effectively.

In light of these findings, the subsequent memo will undertake a comparative analysis of the de jure and de facto diagonal accountability mechanisms in Korea. ■

References

Choi, Jaedong, and Jinman Cho. 2020. “Do National Election Commission’s Institutional Design and Workforces Have an Impact on Electoral Integrity?” Journal of Parliamentary Research 15, 2: 145-170.

Forster, Reiner, Carmen Malena, and Janamejay Singh. 2004. “Social Accountability: An Introduction to the Concept and Emerging Practice.” World Bank Working Paper No. 31042. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/327691468779445304/social-accountability-an-introduction-to-the-concept-and-emerging-practice (Accessed August 14, 2024)

Grimes, Marcia. 2013. “The Contingencies of Societal Accountability: Examining the Link between Civil Society and Good Government.” Studies in Comparative International Development 48, 4: 380-402.

Kim, Jung. 2023. “Horizontal Accountability and Democratic Resilience: The Case of South Korea in Comparative Perspective.” ADRN Working Paper Series. May 11. http://www.adrnresearch.org/publications/list.php?cid=3&idx=312 (Accessed August 14, 2024)

Kim, Soo Jin. 2008. “A Study of Opposition Party in Park Chung Hee Era.” Korea and World Politics 24, 4: 27-59.

Luhrmann, Anna, Kyle Marquardt, and Valeriya Mechkova. 2020. “Constraining Governments: New Indices of Vertical, Horizontal, and Diagonal Accountability.” American Political Science Review 114, 3:811-820.

O’Donnell, Guillermo A. 1998. “Horizontal Accountability in New Democracies.” Journal of Democracy 9, 3: 112-126.

Peruzzotti, Enrique, and Smulovitz Catalina, eds. 2006. Enforcing the Rule of Law: Social Accountability in the New Latin American Democracies. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Rose-Ackerman, Susan. 1996. “Democracy and ‘Grand’ Corruption.” International Social Science Journal 48, 149: 365-380.

Schedler, Andreas, Larry Diamond, and Marc Plattner. 1999. The Self-restraining State: Power and Accountability in New Democracies. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

[1] For the English translations of Korean laws, I rely on the Korean Law Translation Center founded by the Korea Legislation Research Institute, https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/main.do.

[2] Article 41 Paragraph 1 states that “the National Assembly shall be composed of members elected by universal, equal, direct and secret ballot by the citizens.” Article 67 Paragraph 1 states that “the President shall be elected by universal, equal, direct and secret ballot by the people.”

[3] Paragraph 5 of Article 114 states that “No member of the Commission shall be expelled from office except by impeachment or a sentence of imprisonment without prison labor or heavier punishment.”

[4] Paragraph 6 of Article 114 states that “The National Election Commission may establish, within the limit of Acts and decrees, regulations relating to the management of elections, national referenda, and admіnistrative affairs concerning political parties and may also establish regulations relating to internal discipline that are compatible with the Act.” Paragraph 1 of Article 115 states that “Election commissions at each level may issue necessary instructions to admіnistrative agencies concerned with respect to admіnistrative affairs pertaining to elections and national referenda such as the preparation of the pollbooks.”

[5] See this news article for more details: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-40824793 (Accessed on March 2, 2024).

[6] Article 14, Paragraph 1 (Suspension, Warning, etc. for Violations of Election Laws) states that where a member or staff of each election commission discovers a violation of an election law in the course of performing his/her duties, he/she shall halt the violation, issue a warning or corrective order, and may request a competent investigation authority to launch an investigation or file a criminal charge if such violation is deemed significantly detrimental to the impartiality of an election or an order of suspension, warning, or correction is not complied with.

[7] The Political Parties Act, Article 37, Paragraph 2 states that the activities of political parties promoting their own policies and current political issues without supporting and recommending the specific political parties or the candidates for election to public offices (including persons intending to become the candidates) or opposing them by utilizing printed materials, facilities, advertisements, etc., and activities for recruiting party members (excluding door-to-door visits) shall be guaranteed as normal activities of political parties.

[8] The Political Parties Act, Article 37, Paragraph 4 states that if the purposes or activities of a political party are contrary to the fundamental democratic order, the Government may bring an action against it in the Constitutional Court for its dissolution, and the political party shall be dissolved in accordance with the decision of the Constitutional Court.

■ Sunkyoung Park is a Professor in the Division of Global Korean Studies at Korea University.

■ Edited by Hansu Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | hspark@eai.or.kr

Center for Democracy Cooperation

Asia

South Korea

Democracy

Democracy Cooperation

Asia Democracy Research Network

![[ADRN Working Paper] Democratic Backsliding in South Korea](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20250702151055558995988(0).jpg)

Working Paper

[ADRN Working Paper] Democratic Backsliding in South Korea

Asia Democracy Research Network | 2024-08-23

![[ADRN Working Paper] The Impact of the Millennials and Gen Z on Democracy in Northeast Asia](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/202505231731371005535793(0).jpg)

Working Paper

[ADRN Working Paper] The Impact of the Millennials and Gen Z on Democracy in Northeast Asia

Asia Democracy Research Network | 2024-08-23