![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Japanese Voters Punished the Ruling LDP in the 2024 General Election Amid Political Party Corruption](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20250403154826822722199.jpg)

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Japanese Voters Punished the Ruling LDP in the 2024 General Election Amid Political Party Corruption

Commentary·Issue Briefing | 2024-11-15

Naofumi Fujimura

Professor, Graduate School of Law, Kobe University

Naofumi Fujimura, Professor at Kobe University, examines the background and impact of Japan’s slush fund scandal on the recent general elections and the broader political landscape. The scandal, involving questionable fundraising practices within the ruling party, eroded voter trust and shifted support toward opposition parties. Fujimura emphasizes that, although economic issues remained the primary concern of voters, the scandal intensified demands for political finance reform. Key reforms being discussed include abolishing policy activity funds and requiring legislators to disclose the breakdown of policy research funds, amid intensified public scrutiny.

Leadership Change Amid LDP Slush Fund Scandal

On August 14, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida declared that he would not run in the upcoming Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) presidential election in September and would resign from his role as prime minister. He stated that the main reason for his decision was to take responsibility for the LDP’s “slush fund” scandal.

The term “slush fund scandal” refers to fraudulent practices surrounding political fundraising parties organized by factions within the LDP. These factions, along with individual legislators, have held fundraising parties by selling party tickets, typically priced around 20,000 yen (equivalent to USD 130), to corporations and individuals. Party tickets serve as a de facto political donation, as event expenses (e.g., food, beverages, and venue costs) are kept minimal, and some purchasers do not attend.

The scandal came to light in November 2022, when the Shimbun Akahata, the official newspaper of the Japanese Communist Party (JCP), reported that major purchasers of party tickets from five factions were absent from political fund reports submitted to each prefecture’s election admіnistration commission. In November 2023, it was further revealed that the Tokyo District Public Prosecutor’s Special Investigation Division was pursuing charges related to these political fund issues, which drew considerable attention to the scandal. When political fundraising parties were held, factions required their legislators to sell a specified number of tickets. However, the factions did not disclose ticket sales revenues in political fund reports, nor did legislators report receiving these funds from factions, which constituted a breach of the Political Funds Control Law. In essence, the term “slush funds” refers to the transfer of funds from factions to legislators that is not reported in political fund reports. A total of 85 members from the Abe and Nikai factions received such funds, with the amounts ranging from 40,000 yen (equivalent to USD 260) to 51.54 million yen (equivalent to USD 330,000).[1]

In the LDP presidential election held on September 27, Sanae Takaichi received the highest number of votes, followed by Shigeru Ishiba with the second highest number of votes in the first round. However, as Takaichi were unable to secure a majority, a second-round election was held between Takaichi and Ishiba, resulting in Ishiba’s election as party president.

Lower House Election Results

Ishiba was designated as the new prime minister on October 1. He announced the dissolution of the lower house of parliament a mere eight days after becoming prime minister. Ishiba sought to leverage the high initial approval rating of his cabinet.

The LDP did not nominate 12 legislators who did not report the transfer of funds from their faction in their political fund report (i.e., those who received slush funds) and barred 37 others from running on a proportional representation (PR) list. The lower house employs a mixed electoral systеm comprising single-member districts (SMDs) and PR. This systеm allows candidates to run in both SMD and PR tiers, with those who lose in an SMD still having the opportunity to be elected through a PR list. Legislators who were restricted to running in an SMD were less likely to be reelected.

Nevertheless, this initial move to exclude corrupt politicians soon became tarnished as the election campaign period began on October 15. On October 23, the Shimbun Akahata reported that the LDP headquarters had transferred 20 million yen to the local party branches of candidates who had received slush funds and were not nominated. While these transfers were legal, voters reacted strongly against this de facto support for unnominated candidates. The LDP’s insufficient response to the slush fund scandal further eroded public support for the party.

The results of the October 27 election were striking, with a substantial loss of seats for the ruling LDP and Komeito (see Table 1). The combined total of 215 seats fell short of the 233 seats required for a majority in the 465-seat lower house. In particular, the LDP’s seats dropped from 247 before the election to 191. Among legislators who had accepted slush funds, only four of the twelve who had run as unnominated or independent candidates were elected, while only 14 of the 34 candidates who had run solely in an SMD won a seat.

Komeito also saw its seats reduced from 32 to 24. It is noteworthy that the recently appointed party leader, Keiichi Ishii, who assumed the position on September 28, lost his seat. Additionally, the party was unsuccessful in securing any seats in Osaka Prefecture, a region where it had previously held four seats in the 2012, 2014, 2017, and 2021 elections.

Conversely, certain opposition parties experienced notable gains in their representation. The Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) experienced an increase in its seats from 98 to 148, and the Democratic Party for the People (DPP) saw a notable rise in its representation, increasing from 7 to 28 seats. The Japan Innovation Party (JIP) won all 19 seats in Osaka Prefecture but struggled in other prefectures, resulting in a reduction of its total seats from 44 to 38. Meanwhile, the JCP saw a reduction in its seats from 10 to 8. Additionally, new minor parties made notable advances: Reiwa Shinsengumi from 3 to 9 seats, the Sanseito from 1 to 3, and the Conservative Party of Japan (CPJ) from 0 to 3.

Table 1. Number of Seats in the 2024 Lower House Election

|

|

Before Election |

After Election |

|

Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) |

247 |

191 |

|

Komeito |

32 |

24 |

|

Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) |

98 |

148 |

|

Japan Innovation Party (JIP) |

44 |

38 |

|

Democratic Party for the People (DPP) |

7 |

28 |

|

Japanese Communist Party (JCP) |

10 |

8 |

|

Reiwa Shinsengumi |

3 |

9 |

|

Sanseito |

1 |

3 |

|

Social Democratic Party (SDP) |

1 |

1 |

|

Conservative Party of Japan (CDJ) |

0 |

3 |

|

Others |

22 |

12 |

|

Total |

465 |

465 |

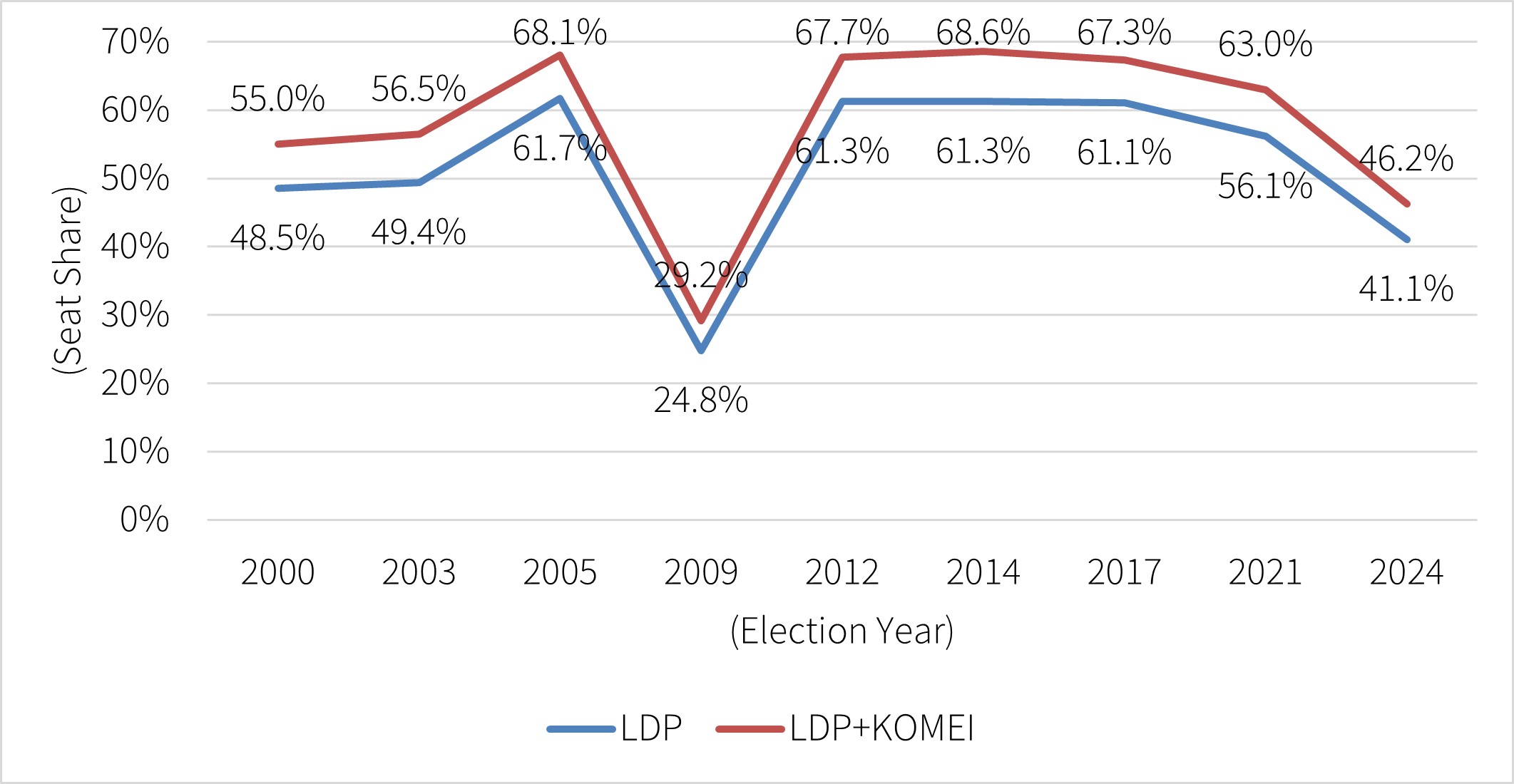

The outcome of this election demonstrates a significant shift from the party systеm that had prevailed in Japan from 2012 to 2024. Since returning to power in 2012, the LDP had enjoyed a period of one-party dominance compatible to its rule from 1955 to 1993, which was known as the “1955 systеm.” In the 2012, 2014, and 2017 lower house elections, the LDP alone secured over 60% of seats, while the LDP-Komeito coalition consistently held a two-thirds majority, thereby enabling them to override upper house rejections in the lower house (Figure 1). The inability of the LDP, even with Komeito, to retain a majority in the 2024 election signifies the end, at least for now, of the LDP’s 12-year period of dominance since 2012.

Figure 1. Seat Share of the LDP and Komeito

What factors contributed to the LDP’s significant seat losses, while the CDP and the DPP experienced an increase in seats? The primary reason was the defection of the LDP’s supporters. According to an exit poll conducted by Kyodo News (Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 2024-10-29: p. 7), 31.8% of respondents identified as LDP supporters, representing a notable decline from the 40.4% recorded in the 2021 election. However, this figure was comparable to the 32% recorded in the 2017 election, during which the LDP secured 61.1% of the seats. This indicates that the decline in LDP supporters did not directly lead to the party’s seat losses in 2024. Instead, a distinctive feature of this election was that only 69% of LDP supporters voted for the party in PR, down from 77% in 2021, 82% in 2017, and 79% in 2014. Significantly, in this election, 7% of LDP supporters voted for the CDP in PR, 6% for the DPP, and 4% for the JIP. The defection of LDP supporters played a significant role in the party’s loss of seats.

In other words, the substantial increase in seats for the CDP did not appear to result from an expansion of its own support base. The Kyodo News exit poll indicates that 17.7% of respondents identified as CDP supporters, representing a slight decline from the 18.1% in 2021. However, the proportion of LDP supporters who voted for the CDP in PR increased from 4% in 2021 to 7.1% in 2024. Once again, the defection of LDP supporters—particularly their votes for the CDP—contributed to the CDP’s seat gains.

While the slush fund scandal was a major issue, economic concerns were the primary focus of voters. As indicated by an exit poll conducted by Jiji Press, the most pivotal policy concern for voters was “economic conditions, employment, and wage increases” (35.8%), followed by “pensions, medical care, and elderly care” (17.6%), and “child-rearing and measures for the declining birthrate” (12.9%). “Politics and money and political reforms” ranked fourth (9.2%) (Jiji Press 2024-10-27). Voters’ dissatisfaction with the LDP government’s economic and social security policies were the primary factors contributing to its electoral defeat. Real wages exhibited a decline for 26 consecutive months from April 2022 to May 2024, partly due to inflationary pressures that imposed economic hardship on individuals. Additionally, voters articulated concerns regarding their future prospects in relation to retirement, healthcare, and child-rearing. In conclusion, the LDP’s defeat cannot be attributed solely to the issue of slush funds alone; rather, it can be seen as a response to public dissatisfaction with living conditions and social security policies.

Weakened Minority Government Pursues Political Financing Reforms

In a press conference held on October 28, Prime Minister Ishiba officially stated that the government is not considering a coalition with any political parties other than Komeito at this time. Similarly, Yuichiro Tamaki, a leader of the DPP, which holds policy positions most closely aligned with those of the LDP, also declared at a press conference on October 29 that the party has no intention of joining the LDP and Komeito coalition. As a consequence, the Ishiba government, operating as a minority government, is likely to face significant political challenges. In order for the government to pass budgets and bills, it will require the support of opposition parties. Additionally, a motion of no confidence in the government could be initiated at any time.

Meanwhile, the major opposition parties, including the DPP, the CDP, and the JIP, are facing intense scrutiny from the public regarding the extent and manner of their cooperation or conflict with the Ishiba government. This stance may have an impact on their future level of public support and seat counts. In light of the forthcoming upper house election scheduled for July next year, it seems inevitable that Japanese politics will experience a period of uncertainty and instability in the run-up to the election.

Prime Minister Ishiba has articulated his commitment to address issues pertaining to the intersection of politics and finance. This includes the proposed abolition of policy activity funds, which are currently allocated to legislators by political parties without a requirement for public disclosure of their use. Furthermore, he advocates for the mandatory disclosure and return of the one million yen granted monthly to legislators as policy research funds. The opposition parties have established these strengthened political finance reforms as a prerequisite for their cooperation with the government. In the context of intense public scrutiny, Prime Minister Ishiba will be compelled to navigate negotiations with the LDP, its coalition partner Komeito, and the opposition parties on these pivotal matters, thereby positioning political finance reform as a central item on the political agenda. It remains to be seen whether he will succeed in these political reform endeavors. ■

References

Jiji Press. 2024. “景気・賃上げを重視 投票先判断、年金も優先―出口調査【24衆院選】” (Emphasis on the economy, wage increases, and pensions prior to voting decisions) October 27. https://www.jiji.com/jc/article?k=2024102700809&g=pol (Accessed November 7, 2024)

Nihon Keizai Shimbun. 2024. “石破内閣支持32%、18ポイント減 共同通信世論調査” (Support for Ishiba Cabinet 32%, down 18 points: Kyodo News poll) October 29.

[1] The LDP had six factions: the Abe Faction (96 members as of January 2024), the Aso faction (55), the Kishida faction (46), the Motegi faction (45), the Nikai faction (38), and the Moriyama faction (8). Five factions—excluding the Aso faction—dissolved by ceasing regular meetings, closing offices, and deregistering as political organizations.

■ Naofumi Fujimura is a Professor at the Graduate School of Law, Kobe University.

■ Edited by Hansu Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | hspark@eai.or.kr

Center for Democracy Cooperation

Asia

Japan

Democracy

Democracy Cooperation

Asia Democracy Research Network

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] India`s State of Emergency at 50: Enduring Lessons for Democracy](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/202507238542964953507(0).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] India`s State of Emergency at 50: Enduring Lessons for Democracy

Niranjan Sahoo | 2024-11-15