![[ADRN Issue Briefing] The Pandemic Situation in Myanmar is Getting Worse Under the Military Government](../images/bg_tmp.jpg)

[ADRN Issue Briefing] The Pandemic Situation in Myanmar is Getting Worse Under the Military Government

논평·이슈브리핑 | 2021-08-10

Khine Win

[편집자 주]

Amid the ongoing military rule in Myanmar, the public health crisis has been reaching new heights. According to Khine Win, founder and director of Sandhi Governance Institute, hopes were high among citizens in Myanmar for a healthcare sys-tem that could aptly combat the COVID-19 pandemic upon the election of the NLD in November 2020. However, progress has been reversed and is yet stalled under the elongated military rule. Despite dire civil health and poverty predictions issued by the UNDP, World Food Programme, and other international organizations, the military government turned a blind eye to their warnings, exacerbating the ongoing health crisis. COVID-19 cases have been increasing exponentially, with the number of actual COVID-19 cases expected to be higher than official numbers. News that military rule is expected to continue into 2023 paints a dull future for the public health situation in Myanmar.

The Third Wave of COVID-19 and Myanmar

Since June 2021, the third wave of COVID-19 has been raging wildly in Myanmar and untold sufferings of the general public cannot be measured in merely the number of infection and fatality rates. Official data on infection and fatality mask the extent of the pandemic and the havoc wreaked by it. The contrast between infection and fatality rates and the military’s State Administration Council (SAC)’s response and deposed NLD government’s during the first and second wave of the pandemic is reflected in the news media reporting on oxygen shortages, long queues in front of pharmacies to purchase life-saving medicines for the loved ones and dead bodies at the crematorium. This article will analyze how changes in regime type and governance can have a huge impact on the socio-economic lives of ordinary people.

2020 was a critical year for Myanmar’s democratization as the multi-party general election was scheduled to be held for the third time. If the ruling NLD and democratic parties won, it would be in line with the democracy theory of two turnovers respecting the outcomes of free and fair elections’ results. It was also crucial that the NLD-led government renew legitimacy and strengthen public mandate. Most of the people held high hopes in the post-election period because NLD was implementing Myanmar Sustainable Development Plan (2018-30) and believed improvement of socioeconomic conditions in terms of infrastructure, health and education would be accelerated.

Unfortunately, Myanmar could not avoid the scourge of the global pandemic and on March 23, 2020, the Government of Myanmar announced the first two cases of COVID-19 and alerted the public to prepare to overcome it. Surprisingly, all cases were imported from the West and not from China, where the pandemic started in late Dec 2019 and whereby Myanmar shares a long border.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought on simultaneous crises. In order to control the spread of the virus mobility and social contacts had to be limited. However, this negatively affected the economy. Therefore, governments around the world need to flatten both the pandemic and economic recession curves as advised by Pierre Olivier Gourinchas (2020)[1] depending on the resources that can be mobilized by the respective country’s government.

NLD Government’s Response to COVID-19

Developing countries have faced greater challenges in dealing with the pandemic than developed countries due to their limited fiscal space, debt burden, and fragile healthcare infrastructure. Myanmar is not an exception and because of the perennial underinvestment in the health sys-tem, Myanmar has one of the poorest healthcare sys-tems in the Asia-Pacific region. One can only imagine how difficult it is to respond to a national-scale health crisis when Myanmar has less than 1 physician per 1000 and 9 hospital beds per 10,000 people.[2] In addition, although government expenditure on health has increased between fiscal year 2011/12 and 2017/18 from 0.19 percent to 1.1 percent of GDP, it is still low compared to neighboring countries. Additionally, private expenditure accounts for 76% of total expenditure on health which led caused poor households to fall into poverty. Therefore, if health resources are reprioritized to COVID-19 response, millions of citizens will be left without access to essential health services.[3]

On the economic front, although Myanmar’s public debt to GDP ratio was not at a distress level and one of the fastest-growing countries in the region, the government had limited fiscal space and monetary tools due to military rule that lasted for over two decades. The banking sector had a high level of Non-performing loans (NPLs) even before the COVID-19 pandemic despite substantial growth within the sector and despite the fact that the Central Bank of Myanmar was initiating prudential regulations to strengthen and liberalize the financial market.

Taking these sys-temic risks and structural vulnerabilities into consideration, the NLD had initiated COVID-19 and economic response policies. As a general principle, the government adopted the “No One Left Behind” mantra. The National-level Central Committee on Prevention, Control and Treatment of Covid-19 chaired by the State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was formed on Jan 30, 2020, and on March 13, 2020, The Covid-19 Control and Emergency Response Committee led by military-appointed Vice-President Myint Swe was formed together with working committees to alleviate the negative economic impact on businesses. Initially, most people thought Myanmar would be more hit hard economically than health-wise. This is due to its limited participation in globalization and limited connectivity despite its porous borders with India, China, Thailand, Laos, and Bangladesh. World Bank also downgraded the economic growth rate of Myanmar from 6.8 percent in fiscal year 2018/19 to 0.5 percent in fiscal year 2019/20.[4]

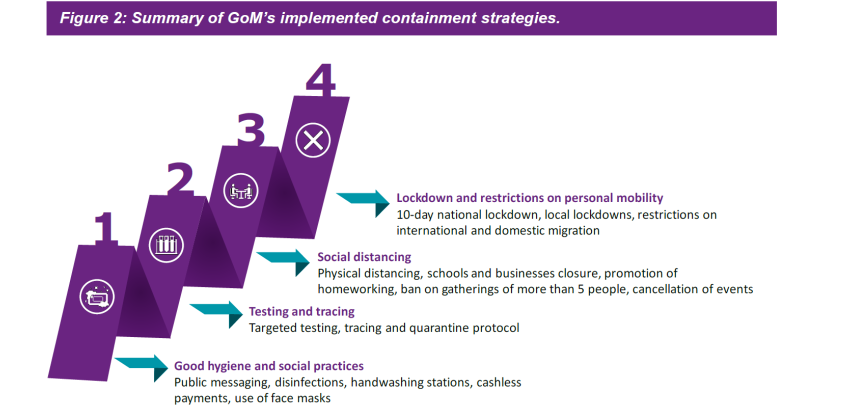

Figure 1: Containment Strategies and CERP (Covid-19 Economic Response Plan) by NLD Government

Source: Emanuele Brancati et al (2020), Coping with Covid-19, International Growth Center

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Myanmar, the NLD took a holistic approach in responding to the health crisis The containment strategies were focused on controlling the infection while CERP was focused on economic recovery. Even before CERP, the government of Myanmar had initially announced an economic stimulus package worth nearly $70 million which included loans and deferral of tax payments and tax exemptions for businesses that were hit the hardest by the pandemic such as travel and tourism businesses and restaurants.[5]

Although CERP is known as an economic relief plan, it also includes steps to strengthening the healthcare sys-tem through procurement and importation of key medical products, recruitment of medical personnel, upgrading health facilities, and extending/improving quarantine centers, and increasing access to COVID-19 funding. Goals 3 and 4 focused on easing the impact of laborers/workers and households. Under the aforementioned goals, in-kind, cash, and social transfers were distributed to poor households and unemployed laborers who were Social Security Board (SSB) members, workers in formal sectors. Universal electricity tariffs subsidies of up to 150 units were implemented to alleviate the impact on household incomes. Although there were challenges and obstacles when trying to reach the target groups, CERP attempted to address issues in all sectors that were impacted by the COVID-19 and implemented both monetary and fiscal policies.

As a follow-up to CERP, the government announced the Myanmar Economic Recovery and Reform Plan (MERRP) in October 2020. It was a medium to long-term response to the economic damage caused by COVID-19. It was launched during the peak of the second wave in Myanmar but exuded the sense of sanguine views and confidence in the society’s resilience to recovery and continue on the path of reforms and democratization for a prosperous, peaceful, democratic country.

Social Mobilization and Leadership

Aware of the fact that the pandemic could not be effectively controlled without public participation, the NLD and State Counselor initiated mass mobilization strategies. Such strategies were releasing videos showing the State Counselor washing her hands and activating her Facebook page on 1 April 2020. Other strategies included holding dialogues with key stakeholders including frontline healthcare workers and volunteers on Facebook live, and holding a mask-knitting competition.

Due to high public trust in the government, social mobilization was very effective and could be attributed to the success of controlling the second wave within 4 months despite weak health infrastructure and limited resources. The accusation by the coup council that infection and mortality rates increased considerably due to the holding of elections in November was unfounded as the number of cases started to decrease since that time.

Yangon, the former capital and commercial city of Myanmar, was hit hardest during the second wave, and therefore implemented the containment strategy of test, trace, isolate, and treatment. During this time. quarantine centers and public hospitals needed thousands of volunteers and subsequently, food, accommodations/hotel facilities, and essential drugs donations were made.

On account of social trust in the governemnet and unity of the people, like the title of CERP of “overcoming as one,” individuals and civil society members cooperated and made donations. Of the civil participation, the largest was “We Love Yangon” that was led by famous philanthropist Daw Than Myint Aung, and it donated and contributed to the quarantine centers. Additionally, during the tracing stage, medical students volunteered to participate. The public was aware that unity and oneness with the NLD government were crucial in order to reduce the risk of the military which was seeking opportunities to take over power from the civilian-led government.

Therefore, social trust and leadership are important in containing the pandemic and in Myanmar’s case, although the second wave was a lot more severe with the positivity rate of 9.5 percent and fatality rate of 2.4 percent until mid-Nov 2020, well above the WHO recommended 5% positivity rate for relaxation of restrictions, Myanmar could, at last, reduce the number of cases to low number and few fatalities.[6] It was predicted that the economy would recover and many firms were planning to resume their activities and make new investments in 2021, particularly after the new civilian government was formed in April 2021.[7]

Post-Coup Myanmar and Third Wave of COVID-19

COVID-19 second wave, despite the fact that it could been overcome, had weakened the economy much more than the first wave. However, the World Bank estimated that it would recover gradually and was projected to achieve a 2 percent growth rate in the 2020/21 fiscal year. However, political stability and international assistance for vaccinations, and economic recovery are two of the most important factors for both medium and long-term development of the country. Mobilizing all the available resources to roll out effective vaccination programs for the majority population in the shortest time possible and make investments in infrastructure and productive sectors are very crucial for Myanmar's sustainable development. Therefore, the NLD had introduced CERP and MERRP while increasing the capacity of the healthcare sys-tem to respond to current and future pandemics effectively and to improve health outcomes. People were also looking forward to the post-pandemic era and the next term of the civilian-led government. The military should not have conducted the coup during this fragile stage of the country. Currently, Myanmar is suffering from multiple crises.

The hope people held for their lives and country came crashing down in February 1, 2021. The country descended into chaos and some analysts prophesied that Myanmar is on the path to become a failed state.[8] Medical doctors led the civilian disobedience movement (CDM) against the military coup soon after SAC took over power from the civilian government and mass protests had occurred (and are still occurring) in Yangon, Mandalay, and almost all over the country. Nearly 50 percent of the healthcare workers are still on CDM (some are in hiding, some are in prison and some are in liberated areas), and as a result, the healthcare sys-tem has almost completely collapsed.[9] Due to internet blackouts, CDM of private banks’ staff, and withdrawal restrictions led to the loss of trust in banks which in turn is pointing to a possible banking crisis. People are short of cash and have to queue for long hours to withdraw less than $350 from ATMs. People could not pay attention to the COVID-19 situation as the military’s brutal crackdowns on the protestors caused vulnerable groups to flee their towns and villages.

Two months after the coup, many reports warned of the dire humanitarian crisis and economic collapse. UNDP published a report titled “Covid-19, Coup D’ Etat and Poverty” in April, and it predicted that poverty would double in 2022, and half of the population would likely fall into poverty.[10] The World Food Program (WFP) estimated that more than 3 million poor people might face hunger and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank downgraded the growth rate from a positive 2 percent in the 2020/21 fiscal year to around -10 percent within two months. Currently, the World Bank’s most recent report further downgraded the Myanmar economy to 18 percent contraction this year compared to 2019/20 due to multiple crises.

The military regime, despite these warnings, refused to acknowledge the risks and decided to ease COVID-19 restrictions and opened schools in June 2021 during the height of the second wave in India and when the Delta variant, a highly transmissible and more severe type, was spreading quickly in neighboring Southeast Asia countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. The military’s coup council SAC single-mindedly focused on consolidating power and intended to show the world that they have the capacity to govern. They intended to prove that they are better than the NLD in containing COVID-19 and managing the economy. Hence, SAC decided to open schools and public places, even amusement parks.

However, the opposite was seen to be true. Since June, new COVID-19 cases were found in the India-Myanmar border town of Kalay in the Sagaing region and gradually spread to other states and regions. The number of cases and fatalities have risen exponentially in July and the positivity rate even reached to more than 38 percent on certain days. Many health experts stated that the actual number of cases and fatalities could be 4-5 times more than official data as the junta’s ministry of health only counted the deaths at hospitals. The worst-hit was Yangon and anecdotal evidence suggests that a large number of households were infected with COVID-19 and many families lost their loved ones due to lack of oxygen, shortage of medicine, and limited access to hospital care.

Compounded to these difficulties is SAC’s seizure of oxygen that was either imported or from private distributors. They also required supplies to receive recommendations from the ward and township level authorities. Their actions can be considered as criminal negligence and deliberate manipulation of policies to utilize COVID-19 for their political legitimacy. Only after the situation became out of control did SAC imposed strict restrictions and closed schools and public offices starting from July 17.

Conclusion

The cumulative infection has more than doubled to over 300,000 cases and according to official data, daily death tolls as of current is nearly ten times the daily mortalities of the second wave. Taking informal data into consideration, total infections might be in the millions and deaths in tens of thousands.

Most of the deaths can be attributed to the lack of hospital care and proper treatment. SAC’s ministry of health does not have the capacity to test, trace, isolate and treat. As mentioned above, the military’s seizure of oxygen, arrest of CDM doctors who tried to provide medical assistance to the infected persons, restraining civil society groups have made the situation worse.

The social trust that binds society and government together has been broken completely since the coup d’etat and people do not care about social distancing rules as they face difficulties in withdrawing money, avoiding military checkpoints, and the looting of the soldiers and arrests. Even though they are infected with COVID-19, the infected are shunned from hospitals and instead die at home. Limited facilities and volunteers at the hospitals and quarantine centers are one reason why very few infected people reported, took tests, and sought hospital care, therefore making tracing almost impossible. The only solution for Myanmar is mass vaccinations but Myanmar’s low level of vaccination of more than 3% of the population does not bode well.

The tragic death tolls caused by the pandemic are largely attributable to the military government’s responses not caring about public health as a priority and people’s mistrust toward this illegitimate government. Accordingly, the right way for Myanmar to recover from the pandemic and worsening economic conditions is to restore democracy. However, General Min Aung Hlaing, who staged the coup with the promise of holding an election within this year, has announced that the military rule will continue into 2023. This is depressing news for both the public health and the democracy of the country. ■

[1] Gourinchas, Pierre Olivier. “Flattening the Pandemic and Recession Curves,” Mitigating the Covid Economic Crisis; Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes, Centre for Economic Policy Research (2020): 31-39.

[2] UNESCAP. Beyond the Pandemic – Building back better from crises in Asia and the Pacific, United Nations Publications, 2021.

[3] “Myanmar Economic Monitor December 2020: Coping with COVID-19,” The World Bank, December 15, 2020.

[4] “Myanmar Economic Monitor June 2020: Myanmar in the Time of COVID-19,” The World Bank, June 25, 2020

[5] Lwin, Nan. “Timeline: Myanmar’s Government Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic,” The Irawaddy, May 26, 2020.

[6] “Myanmar Economic Monitor December 2020: Coping with COVID-19,” The World Bank, December 15, 2020.

[7] Ibid

[8] “The Cost of the Coup: Myanmar Edges Towards State Collapse,” International Crisis Group, April 1, 2021.

[9] “Myanmar Economic Monitor July 2021: Progress Threatened; Resilience Tested,” The World Bank, July 23, 2021.

[10] COVID-19, Coup d'Etat and Poverty: Compounding Negative Shocks and Their Impact on Human Development in Myanmar, UNDP Asia and the Pacific, April 30, 2021.

■ Khine Win is the founder and director of Sandhi Governance Institute, which is organizing public policy and governance trainings for political parties and civil society organizations. Sandhi also conducts research on socioeconomic issues, public procurement, public services. He earned his B.A (English) from Yangon University in 1987 and his Master’s in public policy (MPP) in 2004 from Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore.

■ 담당 및 편집: 백진경 EAI 연구실장

문의: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 209) | j.baek@eai.or.kr

아시아 민주주의 협력

민주주의 협력

아시아민주주의연구네트워크

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?](/data/bbs/kor_issuebriefing/2024032814595548472837(1).jpg)

논평·이슈브리핑

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?

Ken Godfrey | 2024-03-28