![[ADRN Working Paper] Pandemic Crisis and Democratic Governance in Sri Lanka](../images/bg_tmp.jpg)

[ADRN Working Paper] Pandemic Crisis and Democratic Governance in Sri Lanka

워킹페이퍼 | 2021-05-03

Centre for Policy Alternatives

Editor’s note

A national emergency such as the COVID-19 outbreak has urged the Sri Lankan government to pursue new paths in managing the pandemic. However, a series of worrisome developments following the implementation of new structures such as the National Operation Centre for the Prevention of COVID Outbreak (NOCPCO) and other “Presidential Task Forces,” with unclear mandates, have dawned upon the country. The Centre for Policy Alternatives, an independent, non-partisan organization in Sri Lanka explains how the COVID-19 pandemic has posed unprecedented challenges in Sri Lanka, with socio-political effects spanning far beyond the immediate public health and economic crises. The authors state that the political landscape formed following the COVID-19 pandemic has been conducive for democratic backsliding. The involvement of the military and former military officials in COVID-19 management has increased military control over the machinery at the expense of public servants. Sri Lanka was unable to hold elections. The legality of the island-wide lockdown was left unanswered. Political speech was increasingly limited and minorities were oppressed. With the aforementioned events and more unfolding in Sri Lanka upon the outbreak of COVID-19, de-democratization of the government accelerated, resulting in executive aggrandizement and a trend towards militarization. In this regard, the authors call for the government and civil societies to take action to prevent further democratic backsliding in Sri Lanka.

※ 아래는 일부 내용을 발췌한 것입니다. 전문은 상단의 첨부파일을 확인하시길 바랍니다.

The pandemic has posed a number of unprecedented challenges in Sri Lanka, with socio-political effects spanning far beyond the immediate public health and economic crises. Given that the number of issues goes beyond what can be adequately analyzed in a single article, this working paper will focus primarily on an aspect of the pandemic crisis that has particular salience in Sri Lanka and from which lessons can be drawn for other countries in the region. Namely, the challenges to democracy that have emerged during the pandemic period. The paper will look at the ways in which the post-COVID-19 political landscape has been a conducive environment for democratic backsliding, focusing on the period between the beginning of the pandemic response in March 2020 until the time of writing in January 2021. It will look, in particular, at how the policy space opened up by the pandemic has created an ideal context for the acceleration of the processes of executive aggrandizement, militarization as well as the infringement of citizens’ civil liberties.

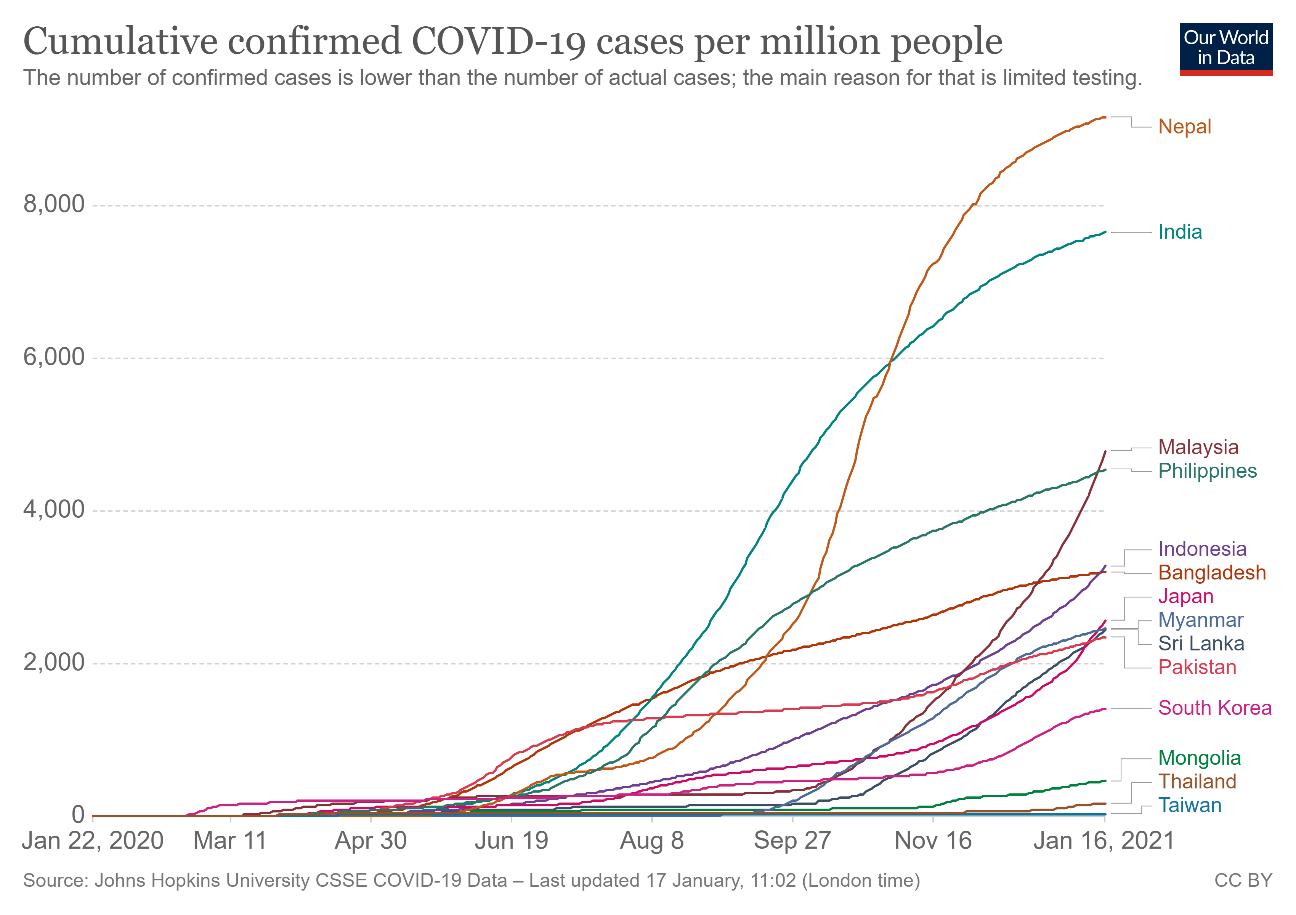

Before discussing the democratic backsliding, the public health background against which it has taken place must be taken into consideration. When this paper was written, the number of cases per million of the population was lower in Sri Lanka than those in the rest of the South Asian region. However, the case rate has been rising rapidly since the beginning of the second wave that occurred in late September. As Figure 1 indicates, while Sri Lanka has not endured the kind of public health crises faced by many other countries in the region, the inability to contain the second wave meant that it has not been able to replicate the kind of success achieved by other Asian countries such as Taiwan, Thailand, Mongolia or South Korea.

Figure 1. Cumulative Confirmed COVID-19 Cases per Million People.

Source: Roser et al. ‘Our World in Data’ (Accessed January 17, 2021) [2]

While initially, the crisis was more of an economic and political one rather than a public health crisis (to the extent that these crises can be separated), the trajectory of increasing cases may bring to the fore the issues in the capacity of the health sys-tem. With 80-90% of cases being asymptomatic, hospital infrastructure and human resources are able to manage the current caseload. However, if the rapid increase in cases continues, it might mean that further investment in hospital capacity may be required. [3]

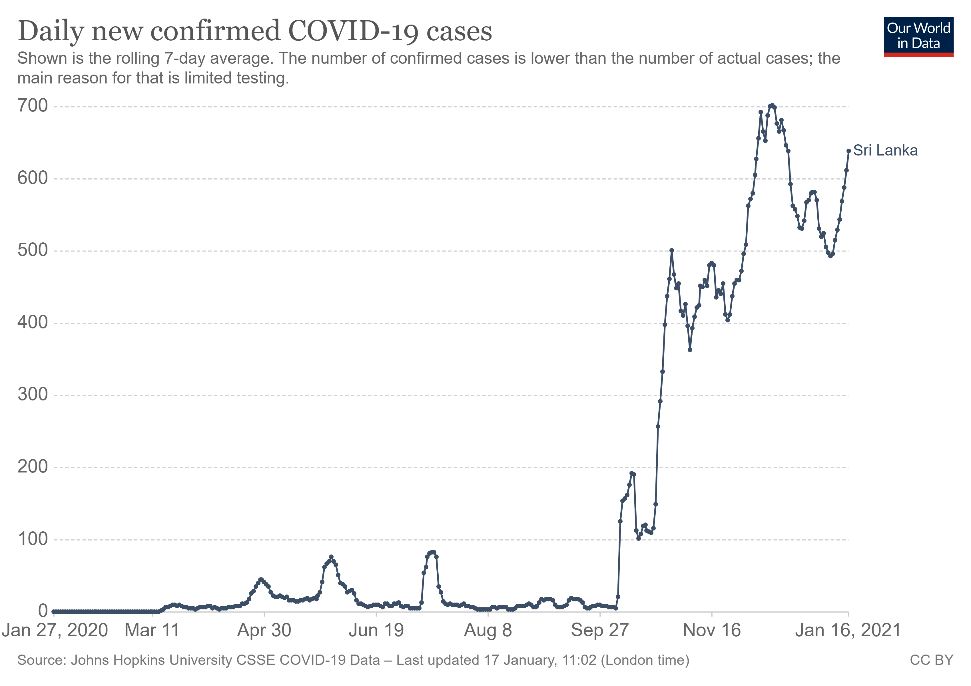

Stringent measures such as the imposition of an island-wide lockdown and restrictions on travel and social gathering account for the initial success in dealing with the first wave. However, these same measures were unable to contain the second wave, as the figures below show.

Figure 2.Daily New Confirmed COVID-19 Cases.

Source: Roser et al ‘Our World in Data’ Accessed 17th January 2021 [4]

The Sri Lanka Government attempted to follow the Chinese model for its pandemic response by focusing on rigorous contact testing but did not prioritize the investment of developing testing capacities. For instance, PCR testing at the initial stages was limited to only test those who came in contact or were involved in identified case clusters, as opposed to random sampling within the population. This created problems down the line as the virus spread in areas outside the cluster cases and created difficulties for tracing the origin of new cases.

In addition to the efforts required to manage the spread of the virus itself, the main challenge during the pandemic has been in dealing with the second-order effects of the lockdown and the measures put in place to curb the spread of the virus (the details of which shall be discussed in the following section). There has been a 27% decrease in average household income during the pandemic period.[5] Food consumption has also decreased by 30% during this time.[6] As such, the need for the provision of necessities, protecting employment, and providing financial relief has become a key challenge during the pandemic. ■

[1] Throughout the year, ADRN members will publish a total of three versions of the Pandemic Crisis and Democratic Governance in Asia Research to include any changes and updates in order to present timely information. The first and second parts will be publicized as a working paper and the third will be publicized as a special report. This working paper is part I of the research project.

[2] Roser et al. “Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19).” OurWorldInData.org, 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus.

[3] “UN Advisory Paper: Immediate Socio-Economic Response to COVID-19 in Sri Lanka” United Nations Sri Lanka, July 2020, https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/LKA_Socioeconomic-Response-Plan_2020.pdf.

[4] Roser et al “Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19).” OurWorldInData.org, 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

아시아 민주주의 협력

아시아민주주의연구네트워크