![[이슈브리핑] The Great Transformation of Korean Social Movements: Reclaiming a Peaceful Civil Revolution](../images/bg_tmp.jpg)

[이슈브리핑] The Great Transformation of Korean Social Movements: Reclaiming a Peaceful Civil Revolution

대통령의 성공조건 | 논평·이슈브리핑 | 2017-04-14

Suk-Ki Kong

Editor's Note

South Korean social movements can be characterized as a strong civil society against a strong state. Korean civil society played a big part in bringing about the country’s democratization. With political party politics still at the infant stage, Korean civic or social movements have produced “over-socialization of social movements,” wherein social movements reach beyond the arena of civil society and intervene in the political realm. Pointing out that social movements in South Korea in the past have turned into violent demonstrations due to clashes with public authorities, Suk-Ki Kong of Seoul National University Asia Center explores why and how Korean civil society chose the path of peaceful civil revolution through the candlelight vigils in 2016. Kong discusses favorable political opportunities and open space, changes in public perception and awareness, and role of internet space and social media among many others in order to explain the Korean candlelight vigil in 2016, which marked the change in Korean civic and social movements. In conclusion, Kong urges that as South Korean civil society recently experienced great changes that gained peaceful, cross-generational consensus, it must now reflect seriously on how to sustain this momentum in the future.

Reviewing the Korean Social Movement Strategy

Korean social movements can be characterized as a strong civil society against a strong state. Under the master frame of democratization, Korean civil society made a dedicated effort to democratize the previous authoritarian dictatorial regime. These efforts culminated in the June uprising of 1987, which contributed to the creation of a direct presidential election sys-tem. Since then, unfortunately, party politics have struggled to escape the backwardness of the clientelism and regional hegemony that dominated under the leadership of Kim Dae-jung, Kim Young-sam, and Kim Jong-pil. With political party politics still unable to grow beyond the infant stage, Korean civic or social movements have produced a so-called “over-socialization of social movements,” wherein social movements reach beyond the arena of civil society and intervene deeply in the political realm, leading reform.

Even within civil society, there are numerous actors who pursue their own interests rather than advocating for the public good by relying on a kind of ‘swarming strategy’ wherein they pretend to argue for the public interest. In other words, Korean society has become a so-called “social movement society” where people engage in strategies of direct action first rather than turning to insider strategies that rely on the formal channels of institutional politics. We believe that social movements should be an effective alternative when the institutional channels for minorities or the socially vulnerable are obstructed. However, if all members of society adhere to collective action strategies as their primary course of action, social distrust and conflict will become even more prevalent. When contentious politics become more popular, state-society conflicts and the resulting costs are greatly increased.

For more than half a century, the strength and dynamism of Korean social movements in the fight for democratization made a lasting impression on the world. However, when traditional forms of direct action are engaged in repeatedly, citizens may quickly become both fatigued and marginalized from the decision-making process. We have repeatedly watched rallies in downtown Seoul led by the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU) as well as protests led by the Korean Peasants League near the National Assembly in Yeouido, both of which result in violent clashes with the police every year. Even as the protests grow more radical, they rarely earn attention from the media. The response to these protests from law enforcement has framed the protestors as violent forces and has responded in a more coercive way, creating a vicious cycle of violent resistance and repression. As a result, freedom of assembly and association, which civil society should enjoy, has been abused. Government authorities and the conservative media strategically frame these rallies and protests as being led by professional demonstrators, ignoring the voices of the people.

Following the inauguration of the Lee Myung-bak administration in 2007, most of the rallies led by civic and social movement organizations have led to violent clashes and even deaths. For example, the Lee administration implemented the Four Rivers Restoration project, which actively promoted privatization favoring big business groups. Park Geun-hye’s administration criticized history education as left-wing and promoted a controversial state-issued national history textbook, made a unilateral agreement on the comfort women with Japan without consulting with the former victims, and was reluctant to investigate the truth of the Sewol Ferry disaster. These are just some examples of how the government has made unilateral policy decisions over the last decade without seeking or achieving social or political consensus.

Additionally, after the IMF bailout in 1997, neoliberal economic globalization policies were further strengthened, exacerbating economic inequality. Economic polarization has unfortunately become a reality. Job opportunities for young adults are declining exponentially and older retirees are competing with young people for jobs in a hyper-aging society. Due to such disastrous internal and external economic difficulties, citizens are calling their country “Hell-Chosun” as a way to express dissatisfaction with government policies regarding youth unemployment, economic inequality, excessive working hours, lack of social mobility, and irrationality in everyday life. Desperate Korean citizens driven to a dead end are craving cognitive liberation from anger, despair, collapse, and discouragement.

Because political opportunity and space are shrinking, the people are inevitably forced to come out to the streets. In 2008, citizens opposed the U.S. beef import policy promoted by the Lee Myung-bak administration. However, their resistance was soon framed as violent and police forcefully suppressed the demonstrations. In 2015, citizens also gathered in downtown Seoul with the aim of fighting against the nationalization of history textbooks. What started as a peaceful rally quickly turned into a violent demonstration due to clashes with public authorities. Many citizens who had expected a peaceful rally turned away as the movement became violent.

When visiting Hong Kong in January 2015, I had the chance to examine the Hong Kong Umbrella revolution. At that time, I found myself wondering why Korean civic and social movements were seemingly unable to employ peaceful strategies like the Hong Kong umbrella movements. In 2016, Korean citizens employed a peaceful and amazing campaign strategy of their own through the candlelight vigils. In this article, I would like to explore why and how Korean civil society chose the path of peaceful civil revolution through the candlelight vigils in 2016. I will also discuss the practical and policy implications of the success of peaceful protests for both the government as well as civic and social movement organizations in the future.

The Hong Kong Umbrella Movement in 2014 and the Korean Candlelight Vigils in 2016

The precursor to the Candlelight Revolution of 2016 took place one year ago. On November 14, 2015, a candlelight vigil against the nationalization of Korea’s history textbooks was held in downtown Seoul. Unfortunately, at the vigil, a farmer named Baek Nam-Ki was hit by police water cannon and later died. On that same day, many citizens gathered in Gwanghwamun Square to oppose the government's decision to mandate state-issued history textbooks, but the peaceful march was blocked by police buses. As a result, a few leading organizations chose to engage in violent protests. Many citizens reluctant to join the violent resistance left the scene. However, numerous rallies and protests against the history textbooks organized by nationwide network organizations followed the same path of the rallies and marches before them, usually leading to collisions with the police. Why do these organizations rely on routine tactics that can cause violent clashes? Is there any other way?

Interestingly, the neighboring Hong Kong Umbrella Movement differed greatly from the repeated downtown rallies in Seoul, Korea. The Umbrella Movement, which lasted from September 27 to December 15, 2014, was a peaceful democratization movement in Hong Kong demanding direct elections for the office of Chief Executive of the Hong Kong government from 2017. Unlike Korean citizens, participants in the Hong Kong movement chose to utilize nonviolent disobedience tactics. Prior to the Umbrella Revolution, the OCLP (Occupy Central with Love & Peace) made preparations for the protests for over a year, abiding by non-violent principles. Students from 24 universities in Hong Kong actually started off the class boycotting a week earlier than expected. Although students led the Umbrella Revolution, the OCLP helped in mobilizing ordinary citizens from different religions, the labor workforce, and those belonging to the middle class to participate. Similar to the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations, the OCLP originally intended to start a movement at Central Station in the financial district of Hong Kong. In fact, the movement began at Admiralty Station when students made a surprise move and occupied the plaza in front of the Hong Kong Government Building. The Hong Kong police fired 87 tear gas rounds at the demonstrators, which only further fueled their anger. Students tried to block the tear gas with umbrellas, which is how the movement came to be known as the “Umbrella Revolution.”

The Umbrella Movement attracted much attention because it created an open space where parents, children, and youths, including middle and high school students, college students and ordinary citizens, could join together. This space was both an open sphere where participants could experience direct democracy by discussing various issues and a cultural space where cultural and artistic activities could be freely shared and open education was provided for students and ordinary citizens. An open podium allowed anyone to speak on any topic for five minutes if they wished. This was an example of a public sphere where citizens learned, understood, and sympathized with new social problems and experienced direct democracy.

The Hong Kong Umbrella Movement clearly shows the key features of peaceful protests including the rule of law, nonviolence, and mutual respect between the citizens and the police. In addition, the volunteer activities of students and citizens during the occupation of the plaza, such as disposal of garbage, maintenance of traffic order, use of public restrooms, and allocation of donated daily necessities showed mature citizenship. Overall, the Hong Kong Umbrella Revolution was characterized by its civil disobedience and nonviolent tactics, sharing and solidarity, equity, cultural art exchanges, and eco-friendly management. Additionally, to counter negative publicity from the Hong Kong government, protestors constantly posted updates on the situation in real time using social media. Furthermore they pressed the Central government to accept their demands by mobilizing transnational advocacy networks.

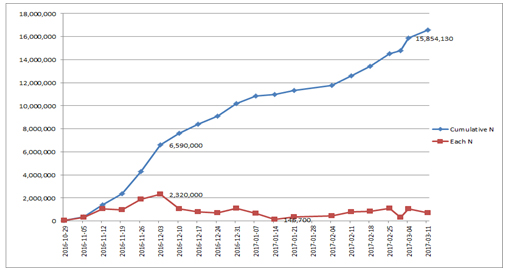

What about the Korean civic and social movements? Starting from the end of October 2016, the peaceful civil revolution through the candlelight demonstration has developed far beyond the Umbrella Movement. First, let us examine the main features of the candlelight protests that allowed citizens to impeach Park Geun-hye. The number of candlelight vigil participants nationally over time is shown below.

Figure 1: Candlelight Vigil Participants (National)

Source:

https://namu.wiki/w/%EB%B0%95%EA%B7%BC%ED%98%9C%20%ED%87%B4%EC%A7%84%20%EB%B2%94%EA%B5%AD%EB%AF%BC%ED%96%89%EB%8F%99,

http://bisang2016.net/

According to Emergency Citizen Action for the Resignation of the Park Geun-hye Administration, the weekly candlelight vigils, which started with just 50,000 people, reached 2,300,000 people nationwide in just one month. In December, the number decreased due to the cold weather, falling to a low of 140,000 on January 14, 2017. However, as people began to fear that the impeachment might be overturned, the number of protestors started to rapidly increase in February. Prior to the impeachment verdict announcement by the Constitutional Court on March 10, 2017, a remarkable number of over 15,000,000 participants came out to protest at the 19th rally. Let’s look at the demographic characteristics of the candlelight vigil participants. In 2008, mostly those in their 20s and 30s participated in the candlelight vigils against U.S. beef imports; however, in 2016, the participation rate of those in their 20s was the highest, followed by those in their 40s and 50s. According to the Pressian News on December 30, 2016, those in their 50s were three times more likely to participate in the candlelight vigil in 2016 than in 2008

(http://www.pressian.com/news/article.html?no=147343).

This means that citizens from all generations participated. Young housewives, the so-called ‘stroller groups’, made up the majority of participants in the 2008 candlelight vigils. But surprisingly, in 2016, many entire families participated. Many parents explained that they came to the plaza with their children in order “not to be a shameful parent.”

The issues dealt with at the rallies were initially tied to calls to impeach President Park Geun-hye, but as the number of rallies increased, the issues addressed extended into the transformation of Korean society as a whole. Among the many issues that caused great domestic shocks under the Park Geun-hye regime, the Sewol Ferry disaster and its aftermath, the tragic death of a 19-year old irregular subway maintenance worker at Guui station, the misogynic murder of a young female near Gangnam subway station, the state-mandated history textbooks, the clandestine agreement of the Korea-Japan ‘Comfort Women’ issue, and the shuttering of the Kaesong Industrial Complex commanded the most attention at the rallies. The people were especially infuriated at the fact that President Park Geun-hye had abused her power by conspiring with a confidante, Choi Soon-sil, to collect tens of millions of dollars from big business groups like Samsung. The accumulated anger of the citizens led them to the plaza to actively engage in peaceful demonstration where they heard and sympathized with each other. Gathering at this public sphere, citizens shared the cognitive liberty of restoring the sovereignty of the people, in which “all the power of the Republic of Korea comes from the people.”

The candlelight vigil became a civic revolution wherein participants encouraged each other and contributed to a nonviolent peace movement. In the beginning, protests were carried out in the traditional way with the slogan ‘Come Together! Let’s get angry! Park Geun-hye step down!’ in order to mobilize the angry public. As the worst parts of the scandal were revealed, the movement spread like wildfire. Rather than just falling into the despairing mindset of “How can this happen in a democratic country?”, people gathered in Gwanghwamun Square and proclaimed “Korea is a democratic republic and all power comes from the people.” Similar to the Hong Kong Umbrella Revolution, the younger generation, ranging from middle and high school students to college students, participated in the candlelight vigils.

As seen in Figure 1, the candlelight vigils spread throughout the country as people held simultaneous rallies in the major cities. In the first week of December, before the vote of the National Assembly to impeach the president, the total number of participants reached more than 2 million. The candlelight vigils based on civil disobedience have become more dominant as opposed to the resistance movements led by strong social movement organizations. Numerous brilliant slogans and songs that included satire and humor were created and shared. The candlelight vigil turned into a kind of festival and cultural space that citizens enjoyed, unlike Korea’s traditional demonstrations. Although some politicians and academics suspected that the candlelit public sentiment and momentum would quickly be defeated, the Candlelight Revolution persisted. In contrast to the peaceful marches in the past that ended in violent clashes with the police, participants strongly requested that nonviolent civil disobedience be the first principle of the candlelight vigil.

Due to the cold weather and the New Year’s holiday, the number of participants in the 12th candlelight vigil on January 14, 2017 declined sharply. Counter-movements from conservative groups opposing the impeachment seized this opportunity to mobilize and gain momentum. They tried to develop a frame of patriotism and security and utilized the Taegeukgi, the national flag of South Korea, as their symbol. As soon as those opposing the impeachment gained power, the citizens supporting it gathered in the square again with a sense of crisis and showed remarkable solidarity with more than one million people attending the 19th rally on March 4, right before the impeachment verdict was announced by the Constitutional Court. Sadly, there appeared to be an extreme ideological discord between the candlelight vigils at Gwanghwamun Square and the Taegeukgi rallies at City Hall. Both groups failed to engage in sound debate on the issues via open discussions and instead denounced each other ideologically, spreading distorted information through social media. The conservative groups sought to maintain peaceful rallies and mobilized cultural symbols and satirical demonstration tactics as well. This can be interpreted as a result of a mutual learning process that violent strategies should no longer be employed to secure the legitimacy of claims and the support of citizens.

Why and How did Korean Social Movements Maintain a Peaceful Demonstration Strategy?

Unlike the candlelight vigil in 2008, the 2016 candlelight vigil went a completely different way: peacefully. I will examine why and how Korean civil society maintained peaceful demonstrations during 2016. First, let us examine why civic and social movement organizations chose a peaceful demonstration strategy. Actually, the movement organizations had no choice but to accept the demand from below for a nonviolent civil disobedience strategy.

In 2016, many participants, especially families, demanded peaceful demonstrations in exchange for their support. In contrast, although the tactics of candlelight vigils were mobilized in 2008, they often led to violent clashes. This occurred because of the social movements’ insistence on the traditional strategy, which called for police suppression tactics that resulted in the destruction of peaceful rallies. The movement groups neglected to prepare a new framework or mobilize cultural exercise tactics. There was a lack of concern about who participated, who cooperated, and who potential supporters for the rallies are.

Why are there people filled with only wrath when you go to a rally? We should raise the question of whether only a few activists would end up in violent clashes with the police. On November 14, 2015, a farmer named Baek Nam-Ki was knocked over by police water cannon during a demonstration against the issuance of state-mandated history textbooks. Many citizens participating desired a peaceful rally, but when the demonstrations became violent, many citizens left. The movement organizations tried to integrate diverse and complex frames and deal with all the problems facing society at the same time. Despite their efforts, however, they failed to take into account the various needs of the citizens and all of the obstacles that impeded the sustainability of the movement.

The 2016 candlelight vigils were clearly very different. Civic and social movement organizations with more favorable political opportunities and open space are more likely to mobilize resources to press the government. In the past, they used to mobilize citizens by drawing upon their anger and demand immediate regime change. However, citizens who came to the plaza in 2016 rejected the candlelight campaign strategies of the past, and poured out various opinions on social issues. If anyone tries to organize and lead this massive participation, it is more likely to prevent the voluntary participation process that started from below. Naturally, movement organizations positioned themselves as coordinators to facilitate a horizontal decision-making process and voluntary participation. Participants ranging from young students to the elderly played a key role in the candlelight vigils. They voluntarily composed funny songs with humor and satire that all the participants were able to enjoy. With Article 21 of the Constitution guaranteeing freedom of speech, and the press, and freedom of assembly and association, citizens were able to experience direct democracy through which they communicated and sympathized with each other.

Initially, there were conflicts with the police, but it was the citizens themselves who stressed the principles of nonviolence and civil disobedience and called for peaceful demonstrations. Participants believed that public authority was no longer an enemy, but a friend. Protestors handed out snacks to the police blocking the march and reaffirmed the peaceful demonstration by attaching flower stickers to the police buses. The movement organizations no longer functioned as leaders, but rather acted as facilitators or coordinators for the peaceful protests. Citizens initiated a peaceful candlelight protest strategy from below and the movement organizations followed their lead. If the movement organizations had tried to lead the participants rather than respond to their demands and act in this facilitating role, they would not have gotten the results of the current civic revolution.

Next, let’s examine how the civic and social movement organizations were able to maintain peaceful rallies. Social movement scholars argue that movements should provide a collective action framework for potential participants. All of the citizens actively accepted the master framework of ‘justice’ in the face of an immensely unjust situation wherein Choi Soon-sil monopolized state affairs. The citizens carrying the candles were asked to strongly confirm the sovereignty of the people in the square and to defeat the forces that had privatized state power. The candlelight vigils also provided a public sphere for democratic learning, allowing citizens to overcome their political apathy. A variety of cultural arts programs were organized voluntarily to enable participants to be proud of themselves for being a part of a direct democracy. In a process such as this, everyone had an opportunity and a sense of belonging through participation.

It also appears that the Internet and social media enabled greater voluntary participation. Thus, we need to pay more attention to the role of internet space and social media in the great transformation of Korean social movements. In an extremely isolated life, individuals struggle to overcome their feelings of frustration, anger and isolation and say, “Perhaps I am the only one? What if there is no one in the square?” However, by meeting online friends and sharing their thoughts in an offline space, they were able to sympathize with each other more easily and join together to advocate for a shared viewpoint in the square. Without understanding, communication and mutual empathy across a variety of socio-economic backgrounds and age groups, the peaceful candlelight vigils would never have lasted. In this way, citizens participated in the so-called social construction process of sharing and reconfiguring social meanings of the candlelight by voluntarily participating in both online and off-line activities.

In addition, we need to pay attention to the institutional approach for sustaining the peaceful candlelight vigils. Some cause of lawyers filed a challenge against the convention that the police have banned demonstrations within 100m of the Blue House, presidential office with reference to the ‘Law on Assembly and Demonstration.’ However, even though the freedom of assembly has already been guaranteed by the Constitution, the police decided to ban all the assemblies because of the risk of safety accidents such as traffic disturbance and the crushing accident.

By highlighting that all the 2016 vigils would be held legally and peacefully, the coordinating groups swiftly set up a legal team to file a court injunction against the police ban. The court accepted the request of the candlelight protesters, and issued a resolution saying, “The freedom of assembly is the right of citizens as is the right to decide the time, place, method and purpose of the assembly.” The court ruled that “the public interest in traffic is hardly comparable to the freedom of assembly and demonstration.” Thus, the coordinators announced the court ruling both offline and on social media to encourage families, lovers, and friends to freely come to this candlelight vigil. This resolution may hopefully act as a significant impetus for movement groups to adhere to the principles of nonviolence and peaceful rallies in the future.

Through this institutional strategy, the movement groups secured the trust of the citizens and the candlelight vigils were able to proceed peacefully. This institutional approach enabled more and more citizens to participate in the peaceful candlelight vigils of 2016. As a result, the citizens themselves have learned that they not only have the right to assemble and rally, but the right to enjoy such activities. Police who have shut down rallies through violent means in the past need to use this judgment as an important basis for persuading counter-movements to the candlelight vigils.

Practical and Policy Implications

First, let us consider the practical and policy implications for social movements and their relationship with the media. The candlelight vigils specifically confirmed the synergic collaboration between online and offline activities. In order to mobilize potential participants who are online, various channels should be set up so that public participation can be done freely in a horizontal manner. It is the online space where individual participants without any organizational affiliation can have the courage to act as mediators to encourage others to come out to the square. Practically, Korean social movement organizations should develop a ‘public sphere’ where anyone can voice their opinions on pressing social issues.

In addition, to promote the principle of peaceful assembly, public authorities should respect and guarantee the freedom of assembly and association. Peaceful rallies and protests can lead to violent conflicts at any time if the police, who symbolize public authority, perceive them as potential offenders and try to coercively suppress them rather than protect the rights of citizens to protest. It is also necessary to punish the spread of distorted information, that is, the group or individual mass-producing fake news, to maintain a healthy public sphere that encourages grassroots democracy.

Second, let us consider the practical and policy implications for enhancing public good among citizens. Not all policy decisions should be made by candlelight citizens who gather in the square. When candlelight citizens return to their daily lives, they are easily isolated and have difficulty resisting against the privileged; thus, their pride as a political entity disappears again. It is a great practical task for movement groups to continuously seek policy alternatives that can advocate for the marginalized. The more the politicians listen to the voices of their citizens, the more the citizens recognize that their voices will be reflected in the policy. This increases political efficacy and the voluntary participation of citizens in promoting social values and public good.

Lastly, let us consider the practical and policy implications for communication and social integration beyond ideology and generation in South Korea. Rapid industrialization resulted in a society of people focused only on their own material success but not the public good as a whole. The older generations who filled the Taegeukgi rallies want to be recognized as the generations that contributed to the country’s modernization, and the younger generation under the pressure of the neoliberal economic sys-tem is losing their voice. Social movement groups should be careful not to promote exclusionary frameworks that neglect the practical task of connecting these two generations. Korean society has witnessed the dangers of being divided by ideologies and generations beyond the economic gap. Conservative groups will also gradually lose public support if they persist in advocating the old-fashioned frameworks of anti-communism, regionalism, and growth-first discourse. The government and civil society should make every effort to link both the candlelight protestors and the Taegeukgi protestors.

In conclusion, as Korean civil society recently experienced great changes that gained a greater peaceful, cross-generational consensus, it must reflect seriously on how to sustain this momentum in the future.■

Author

Suk-Ki Kong is a research professor at the Seoul National University Asia Center. He studied sociology and received his B.A. and M.A. from the Department of Sociology at Seoul National University and his Ph.D. from the Department of Sociology at Harvard University. He is also an adjunct professor at the Graduate School of Public Policy and Civic Engagement at Kyung Hee University. His major fields of research are social movements, NGO studies, and political sociology.

민주주의와 정치혁신

대통령의 성공조건