![[Myanmar Special] ① Spring Revolution’s March towards a New Myanmar and the Promising Future of Democracy in Asia](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2022032316555232100815.png)

[Myanmar Special] ① Spring Revolution’s March towards a New Myanmar and the Promising Future of Democracy in Asia

Commentary·Issue Briefing | 2022-03-24

Eun Hong Park

Sungkonghoe University

Myanmar, which has experienced its first military coup in 33 years, is going through a chaotic time. ASEAN has failed to come up with any countermeasures and China has become obsessed with "vulgar pragmatism." However, Myanmar`s people, who have spent 10 years on reform and democratization, are fighting for the country’s democracy from various angles by leading the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) and establishing a National Unity Government (NUG). Eun Hong Park, a professor at Sungkonghoe University, emphasizes that most countries with implicit alliances with Myanmar`s military have non-liberal governance. Referring to the post-coup phase on "Tatmadaw-democratic camp-international community," He argues that Myanmar`s "Spring Revolution" can become an opportunity to create "new Asian values."

1. The Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) Launches the National Unity Government (NUG), the only Legitimate Government

It has been one year since Myanmar sank into crisis. At dawn on February 1, 2021, the Myanmar military or Tatmadaw, which has been called the “state within the state,” launched a coup d’état. It had been just 33 years since the previous coup d’état. The coup forces, led by Commander-in-chief Min Aung Hlaing, detained several members of the National League for Democracy (NLD) party, including State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint, and declared a year-long state of emergency. The ghostly rumors of a coup d’état following the election on November 8, 2020 suddenly became real, and the NLD government led by Aung San Suu Kyi collapsed just before entering its second term in power.

When the first NLD government (2016-2021) took power on March 30, 2016, it pledged to revise the 2008 Constitution, establish peace through reconciliation with minority populations, and escape poverty through economic revival. Of these promises, it focused primarily on revising the 2008 Constitution, which preserved the authority of the Tatmadaw. There were even rumors in certain corners that the NLD government was trying secure assistance from China to get the Tatmadaw to accept a constitutional amendment. When the NLD took power in 2016, China was the first country that Aung San Suu Kyi visited. As the Rohingya human rights issue soured relations with the West, Aung San Suu Kyi's shift towards China became clear.

However, following the February 1 coup last year, China hid behind the principle of non-interference in domestic affairs before eventually appearing to acquiesce to the military regime. Faith was lost in Aung San Suu Kyi's pro-China path of diplomacy. China's "vulgar pragmatism", its willingness to maintain diplomatic relations with governments severely violating basic human rights if it serves national interests, prevented the UN Security Council from passing a resolution to condemn the military coup. As a result, anti-Chinese sentiment spread rapidly throughout Myanmar to the extent that China was rumored to be behind the coup. However, the country's democratic camp responded quickly. Following the military takeover, members who were elected to Parliament in the general elections on November 8th formed the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), which later launched the parallel National Unity Government (NUG) in April.

Currently, Myanmar is in a state of civil war after the NUG declared a war of resistance against the Tatmadaw in September 2021. The NUG is an underground government within the country that is engaged in all-out war with the Tatmadaw. This is in contrast to the National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma (NCGUB), which was the government-in-exile 30 years ago. The NUG is organizing a number of political forces to replace Min Aung Hlaing's illegal group that brought down the democratically elected government and has announced the building of a true federal democracy through the end of internal ethnic conflicts that have lasted for 70 years. The influence of civil society, which has led the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), in the construction of New Myanmar has proven enormous since the coup.

During the ten-year period of reform and opening, the civic consciousness of the Myanmar people expanded. This is still true a year after the February 1 coup as the people continue to engage in the CDM. As the CDM spread across the country, officers and soldiers increasingly began to leave the barracks, and the youth-led People's Defense Force (PDF) took this opportunity to build momentum for their campaign. As part of the PDF, youths who received military training from outside the city returned and began an armed struggle against the military. One example of this is the attack launched by the PDF against the towers owned by Mytel Telecommunications, a military-owned business. This was the beginning of the organized violent revolt launched in self-defense. The PDF differs from the CDM in that it is expected to replace the Tatmadaw with a federal army comprised of ethnic armed organizations (EAOs).

2. Myanmar’s People Outraged by ASEAN's Incompetence and China’s “Vulgar Pragmatism"

The CPRH, which is composed of MPs who won seats in the November 2020 general election, passed an emergency resolution designating the military forces under Min Aung Hlaing as terrorists immediately following the coup, and asked the international community not to recognize them. The international community, especially ASEAN, of which Myanmar is a member state, faced a heavy burden to respond to this request from the Myanmar democratic camp.

Western nations, including the United States and the European Union, had imposed sanctions on Myanmar in the 20 years prior to the country's political opening in 2011. They suspended arms sales, expelled diplomats who were former members of the military, refused to issue visas for high-level military officers, and suspended all bilateral aid with the exception of humanitarian assistance. The United States designated military-controlled Myanmar an "outpost of tyranny." In contrast, ASEAN, which tends to operate under the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of its member countries, adopted a policy of "constructive engagement," a kind of "change through inclusion," and allowed Myanmar to become a member state in 1997 despite the opposition of Western countries. However, the following year, the Thai Foreign Minister proposed the concept of "flexible engagement" which went beyond the ASEAN policy of non-interference. This proposition was intended to be discussed whenever the policies of one ASEAN member state negatively impacted a fellow member state.

However, following the military coup in Myanmar in 2021, these movements in ASEAN’s norms have not met the expectations of the international community. Most important has been the fact that ASEAN has been unable to cope with the crisis in Myanmar, which is rapidly deteriorating into civil war. For example, in April of 2021, coup leader Min Aung Hlaing went to Jakarta and accepted the Five-Point Consensus to restore peace in Myanmar, but has yet to implement a single point.

Finally, in October of 2021, ASEAN's ten member states aggressively moved to exclude Min Aung Hlaing from participating in ASEAN summits, but Myanmar’s military did not budge. In the beginning of 2022, Hun Sen, Prime Minister of Cambodia and new ASEAN Chair, even visited Myanmar and was warmly received by Min Aung Hlaing. When Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, and several other ASEAN states protested this move, Hun Sen pivoted to a somewhat tougher stance on Myanmar’s military government.

The Tatmadaw's strategy of ignoring the eyes of the international community is not a new one. Even when the United States and other countries increased sanctions against the military following the overturning of the May 1990 election, in which the Aung San Suu Kyi-led NLD won a majority of seats, the Tatmadaw did not change its behavior, nor did it react when Aung San Suu Kyi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her struggles against the military.

This attitude is not unrelated to the friendliness of some members of the international community toward Myanmar’s military government. For example, on March 27, 2021, major powers including China and Russia as well as ASEAN member countries such as Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos sent diplomatic missions to the Armed Forces Day celebration, which was presided over by the military coup government. While the ceremony was being held, members of the Myanmar military and police were slaughtering civilians who were engaged in the CDM.

China's policy of pragmatism, which appeared to overlook the inhumane actions of the Tatmadaw, particularly drew the ire of the Myanmar people. If China actually implemented its policy of non-interference in internal affairs that it emphasized so heavily, then it should have cut ties with the Tatmadaw and engaged in non-intrusive diplomacy that supports neither the military nor the anti-military factions.

During the Cold War, China had no need to be hostile towards Tatmadaw-controlled Myanmar under General Ne Win, who took power through a coup in 1962, as the country walked the "Burmese way to socialism,” unaligned with either the United States or the Soviet Union. Because of this, China remained patient and was not provoked even when the military authorities under Ne Win nationalized much of the country and stole property from Chinese people living in Burma at the time. The nationalization policies enacted by the military elite under Ne Win's leadership belonged to the typical autarky model. Their goals were clear. The first was to end the economic dominance of foreigners, who were building an economic base in mining and commerce even after independence, and achieve the Burmanization of the economy. The other was to prevent the "penetration of neo-colonialism" by creating a fully self-reliant economy that would never again be governed by a foreign power. Although the military revolutionary elites advocated "Burmese way to socialism" as a kind of combination of Buddhism and socialism that distanced itself from materialism and were themselves a kind of non-communist left, their revolutionary line was in fact quite similar to the communist model.

3. Asia's Illiberal Governance and Creeping Sinicization

Looking back now on the early days of Myanmar, it seems as though Jeane Kirkpatrick, a right-wing diplomat in the early days of the Reagan administration, was correct in her cold-blooded assessment of government systems when she said "an anti-communist right-wing dictatorship is preferable to a totalitarian leftist dictator."

In essence, the Tatmadaw's proclaimed revolutionary line of the Burmese way to socialism became the typical political model of military-rule totalitarianism and degenerated into an economy of shortage due to the failure of the state. In contrast, even as anti-communist ASEAN member states Singapore, Indonesia, and Thailand once led to the organization being ridiculed as a "dictator's club," these states managed to succeed in achieving catch-up growth. For example, the Singaporean government's ability to launch the "Asian values" discourse stemmed from its confidence in having achieved an economic miracle. There is a culture of obedience to governmental discipline at the heart of "Asian values" or "Asianness" here, as well as public recognition of and support for illiberal governance's triumphalism based on economic performance. As the end of the Cold War approached, the Asian values discourse challenged liberal triumphalism expressed as "the end of history." The Asian values discourse, which advocates for illiberal governance, asserts "more discipline and less freedom" as a virtue.

However, the illiberal governance put forth by Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore and Mahathir in Malaysia clearly differs from the illiberal governance of the Tatmadaw. If the former achieved strong economic success on the basis of an open policy externally and efficient bureaucracy internally, the latter dragged the state down to the depths of poverty through widespread nepotism and preferential treatment for the military elites while pursuing isolationism.

Thein Sein's government (2011-2016), which pursued a policy of opening and reform that went beyond expectations, accordingly anticipated performance legitimacy. However, the roadmap to “discipline-flourishing democracy” that underlies the 2008 Constitution and controls the majority of Myanmar’s administrative system posed an obstacle to reformation of the system to one that was meritocracy-based. When Aung San Suu Kyi's NLD government took over, it was not easy to simply reform the illiberal military governance of the previous 50 years. This was especially true because the 2008 Constitution stipulates that the Minister of Home Affairs must be from the military. Because of this, Myanmar could not be normalized without a major reform of the 2008 Constitution. Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD's insistence that Myanmar could not have peace and prosperity without changing the 2008 Constitution was another reason that they had the continued absolute support from the public in every election.

Of course, this "NLD syndrome" was perceived by the Tatmadaw as a challenge to discipline-flourishing democracy, an attempt to cross “the red line that should not be crossed.” In the end, the Tatmadaw responded by engaging in the anachronistic military action of a coup. The 2008 Constitution is what enabled the Tatmadaw to engage in a constitutional coup to protect their privileges as the self-styled "fathers of the nation."

Following the coup one year ago, the CDM has become a symbol of the Spring Revolution. The concept of civil disobedience first emerged in the West, where liberalism is a universal value. However, most Western powers actually gave rise to anti-colonial illiberal nationalist movements due to their two-faced attitude of only permitting liberalism within their borders while ignoring the right to liberty of colonized peoples. One example of this is how the illiberal extreme nationalist line of the Tatmadaw was formed in the process of the struggle for independence from British colonialism, which had a policy of divide and rule. In colonial Indonesia, a strong alliance formed between the Japanese fascists and Indonesian nationalists in the struggle for national independence against the Netherlands as an imperial power. Nationalists in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos also turned to illiberal governance as an alternative while they struggled against the colonialism of major powers like France and the United States that hypocritically claimed to advocate liberalism as a universal value. It is within this context that China, as a source of illiberalism, continues to hugely influence the ASEAN countries currently categorized as non-democracies. Although Asian countries have a shared background of liberation from statism as internal colonialism, in the process of decolonization, the difference in the level of acceptance of illiberal governance has created a "multi-speed Asia" as countries move toward liberal democratic rule at different speeds.

Although the Chinese Communist Party has a history of bloodshed as shown in the suppression of the June 4, 1989 Tiananmen Square democracy protests, it continues to survive without any meaningful challenges from civil society. In this way, the Chinese communist model is becoming a manual for how to oppose democracy in Asia. China is a friendly factor in the expansion and maintenance of illiberal governance in Asia. For example, when the United States and other Western countries criticized the Thai military’s coup in May 2014, China gave a free pass to the military that committed the action. This is the "creeping Sinicization" phenomenon threatening democracy in Asia.

The Tatmadaw was the main fighting force against Myanmar’s colonization, but it has become a colonizing force over its own people during the past half century. Before Thein Sein's government began to pursue reform and opening in March 2011, the people of Myanmar were trapped under a "military guardianship" that thoroughly undermined their right to freedom.

However, since the February 1 coup, the Myanmar people have been fighting an all-out war against the military, who seek to return to this nightmare state. The NUG has proclaimed federal democracy as liberal governance that greatly guarantees the autonomy of ethnic minorities. CRPH published a Federal Democracy Charter toward the construction of a federal democracy and simultaneously declared the repeal of the 2008 Constitution. This federal democracy has some distinct differences from the NLD-centered governance structure which has been unable to break free of Burman centralism and remained mired in the charisma of Aung San Suu Kyi alone. This change will be pursued by the National Unity Consultative Council (NUCC), which consists of representatives from CRPH and NUG, civil society organizations, all political parties, the General Strike Committee (GSC), the CDM, Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs), and others. The NUCC, which includes numerous organizations that have led the Spring Revolution, is a sort of revolutionary council and constituent assembly. In addition, they are experimenting with the communication politics of deliberative democracy as an alternative to majority rule democracy, which has the flaw of the tyranny of the majority. It is the central organization that will create New Myanmar and is expected to recreate the Panglong Conference, which agreed to build a federal state after independence and the unified struggle for liberation from British colonial rule.[1]1

4. The Spring Revolution Inducing “New Asian Values” to Open Up New Horizons with Cross- National Significance

Most countries that are silent allies with the Tatmadaw are illiberal and control the right to resistance internally. At the forefront of these allies is China. However, even as NUG Minister of Foreign Affairs Zin Mar Aung emphasized the importance of neighboring countries taking a friendly stance towards Myanmar’s democratic faction, she said that China appears to be attempting to strike an unbiased balance between NUG and the Tatmadaw.[2] This shows that NUG sees China diplomatically as a target for persuasion rather than ostracism.

In connection with this active diplomacy, it is worth noting that illiberal countries such as Singapore have shown "cultivated pragmatism" in their approach by calling for an immediate halt to the violence in the country. Malaysia has also expressed disapproval regarding the coup despite not being fully liberal itself. Even though both of these illiberal countries engage in diplomacy focused on their national interests, they have demonstrated a tendency toward pragmatic diplomacy that is not reluctant to criticize governments that seriously infringe the basic rights of their citizens.

It may thus only be natural that Indonesia, which singularly among the members of ASEAN has a relatively stable liberal government, has been relatively friendly towards the Myanmar democratic camp. As such, these three ASEAN members, Singapore (S), Indonesia (I), and Malaysia (M) have taken the lead within the association in pressuring the Tatmadaw.

SIM cards are a crucial means of communication in the information age. SIM cards first became popular during Myanmar’s reform and opening up period and grew the sphere of public debate that forms the basis of democracy. The cumulative effect exploded into the CDM following the 2021 coup d’état.

The diplomatic power of the NUG is essential to ensure that the three SIM countries can play a role like that of SIM cards in the restoration of democracy in Myanmar. The NUG should develop its diplomatic power so that ASEAN and the three SIM countries refuse to recognize the coup government and pressure the Tatmadaw to retreat to the barracks. The NUG must convince them that Min Aung Hlaing's coup forces are destroying the ASEAN connectivity achieved by the ten member countries. Further, since Min Aung Hlaing's coup forces are the main culprit disrupting the regional value chain, the full diplomatic power of the NUG with the like-minded SIM countries should be unleashed so that large countries like India and China can appreciate this fact.

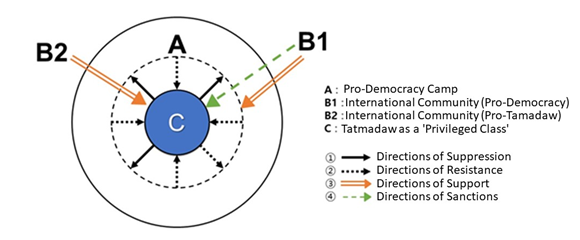

<figure 1>Post-Coup and the Tatmadaw-Democratic Camp-International Community

The European Parliament has taken the official position that the CRPH, representing the MPs who were ousted in the February 1 coup, and the NUG are the only legitimate representative body reflecting the will of the Myanmar people. The United States has joined the European Union in calling for sanctions targeted at Min Aung Hlaing, the leadership, and their enablers, as well as the release of political prisoners including Aung San Suu Kyi. South Korea is the only country in Asia since the coup to have joined the Western camp in levying sanctions against the dictatorship.

As shown in <figure 1> above, B1 includes Western countries such as the United States, the European Union, and South Korea that have decided to impose sanctions on the Tatmadaw. In contrast, B2 shows large countries such as China, India, and Russia that have maintained friendly relations with the Tatmadaw. ASEAN is also divided into countries that are friendly or unfriendly towards the military.

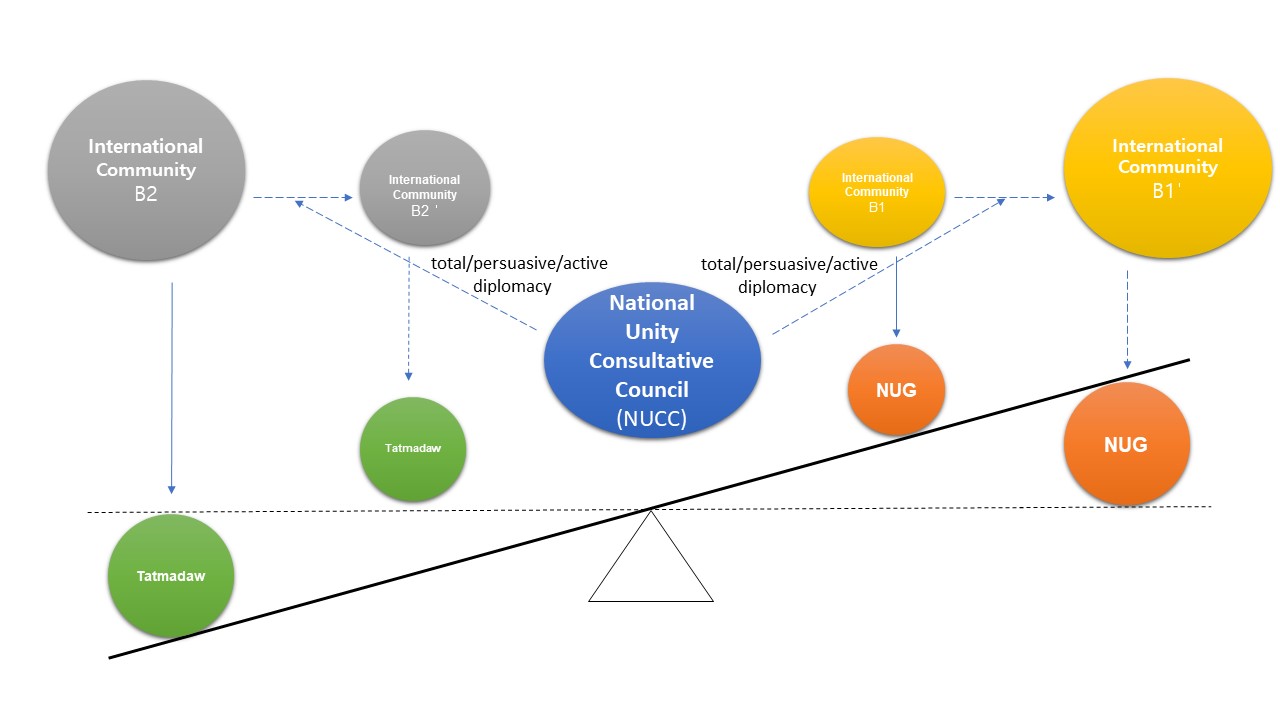

As shown in <figure 2> below, in order to change from B1 to B1' and B2 to B2', the NUCC, which is the broadest platform for political dialogue and includes all political forces in Myanmar's pan-democratic camp, must use its total diplomacy, persuasive diplomacy, and active diplomacy to shift the balance and reduce the influence of the members of the international community that have positive attitudes towards the Tatmadaw and instead increase the influence of those who have positive attitudes towards the NUG.

<figure 2>Power Relationships of the Tatmadaw and Pan-Democratic Forces in the Post-Coup Phase

The coup is an irrational act by the Tatmadaw to usher in a return to the nightmare totalitarian state while disregarding the political chaos and economic ruin that existed before Thein Sein's administration. The people of Myanmar are uniting in the face of the Tatmadaw’s recklessness beyond the differences of generation, sex, class, and ethnicity. In contrast, General Min Aung Hlaing, who serves as the chairman of the Myanmar military's highest decision-making body, the State Administration Council (SAC), with absolute authority, initially declared a state of emergency lasting one year before later extending the period until the year 2023. The military's reappearance on the political front, as it was prior to the reform and opening up of 2011, reveal its commitment to protecting discipline-flourishing democracy.

Following the coup in 1962 led by General Ne Win, who was one of the leaders of the anti-British and anti-Japanese struggles, the Tatmadaw opposed the realization of a federal state that would guarantee the rights to equality and self-determination for minorities and imposed a kind of internal colonial rule on ethnic minorities. Because of this, the Myanmar democratic camp, which is currently preparing a federal democratic constitution and a federal army on the premise of ending discrimination against minorities, has no other path forward.

If Myanmar’s Spring Revolution ends in failure like the 8888 revolution 34 years earlier, it will return to being "the land where time has stopped" as it was under General Ne Win. Sinicization, which promotes illiberal governance, will further quicken and prevent the rooting of liberal democracy in Asia. The future of Asian democracy depends on the success of the Spring Revolution and construction of a new Myanmar. The Asian way put forth by the Spring Revolution goes beyond the basic illiberal “Asian values” paradigm to open new horizons with cross-national significance. ■

* In 1989, the year following the 8888 Democratic Resistance, the Tatmadaw unilaterally changed the name of the country from Burma to Myanmar. Until the NLD decided to participate in the by-election on April 1, 2012, the democratic camp adhered to the national name of Burma in order not to recognize the military government. In this article, considering the context of the times, I will mix the two national names of Burma and Myanmar.

[1] The first people’s assembly was held by the NUCC from January 27 to 29, 2022, and included 38 organizations with a total of 388 attendees.

[2] Please see Minister of Foreign Affairs Zin Mar Aung’s keynote speech at a meeting organized by the NUG representative to the Republic of Korea on January 23, 2022.

■ Eun Hong Park is a Professor in the Division of Social Sciences and the Master of Arts in Inter-Asia NGO Studies (MAINS) at Sungkonghoe University and the Director of the Center for Asian NGO at the university. His major book publications include "Transformation of East Asia: Beyond the Developmental States" and his articles on Myanmar (in Korean) include "Myanmar's Spring Revolution: The Narrative of the Tatmadaw’s Pathway to the Collapse of Guardianship," "Myanmar as Model of ‘Orderly Transition’: The Evolution from ‘Change within Regime to ‘Change of Regime,” “Myanmar 2018: ‘ Rohingya Crisis’ and Democratic Consolidation at Crossroads ,” “National Revolution vs. Civil Revolution: The Comparison between Thailand and Myanmar,” “The Coloniality of Socialism of Our Style as a Post-Colonial Regime Focusing on the Revolution Era of Sukarno and Ne Win,” “South Korean Democracy and Human Rights Diplomacy: The Legitimacy of Diplomatic Sanctions against Burma’s Military Government”. Professor Park studied political science at Thammasat University in Thailand as a visiting Ph.D. student. He was also a visiting researcher at the Political Economy Centre, Faculty of Economics, Chulalongkorn University. He is currently acting as an advisor to the Presidential Commission on Policy Planning, Republic of Korea. He also serves as a counselor of the National Unity Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar Representative to the Republic of Korea.

■ Typeset by Juhyun Jun Head of the Future, Innovation, and Governance TeamㆍResearch Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | jhjun@eai.or.kr

Center for Democracy Cooperation

Strengthening Civil Society Organizations in Myanmar

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20240419123938102197065(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections

Niranjan Sahoo | 2022-03-24

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2024032815145548472837(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?

Ken Godfrey | 2022-03-24