![[Working Paper] Clean at Home, Dirty Abroad: China’s Role in Southeast Asia’s Subcritical Coal Expansion](../images/bg_tmp.jpg)

[Working Paper] Clean at Home, Dirty Abroad: China’s Role in Southeast Asia’s Subcritical Coal Expansion

Rising China and New Civilization in the Asia-Pacific | Working Paper | 2019-05-16

Melanie Hart

Editor's Note

China is the world’s biggest producer and consumer of coals as well as the largest greenhouse gas emitter. Surprisingly, China is also the global leader in clean energy development. Unfortunately, however, this embrace of green energy has not extended to China’s overseas energy infrastructure development projects. Instead, China continues to push forward with building inefficient subcritical coal plants in the less-developed regions rather than helping those nations move toward a low-carbon economy. Melanie Hart uses the Indonesian case to illustrate why China must reconsider its current approach before it becomes a less attractive development partner in the long term.

Quotes from the paper

Introduction

Chinese companies and development banks are playing an increasingly impactful role in global infrastructure development. Domestically, China is reaching the point where economic growth rates are slowing and Chinese firms can often find better infrastructure investment opportunities abroad than they can at home. Through the Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing is providing a mix of diplomatic and financial aid to help Chinese firms find those opportunities in nations ranging from Southeast Asia to Africa to Europe. The types of technologies and projects China brings to those nations will have an outsized impact on the global economy for decades to come.

Chinese firms are particularly active in energy infrastructure. China is the world’s biggest energy consumer, and it is undergoing a massive domestic transition toward cleaner energy sources (Hart, Bassett, and Johnson 2017). Chinese firms are global leaders across multiple renewable energy sectors—particularly wind and solar—as well as in next-generation clean coal technologies. If China leverages its domestic energy innovations to help other nations avoid installing low-efficiency, pollution-intensive coal, that will enable recipient nations to avoid the high economic, social, environmental, and climate costs associated with those projects. At a global level, if China pushes the next wave of energy infrastructure expansion toward more sustainable technologies, that will help the planet avoid some of the most disastrous impacts from global climate change.

Unfortunately, this is not the approach China is taking today. Instead of helping developing nations acquire, install, and operate innovative cleaner energy technologies, China is driving a massive build-out of high-emission subcritical coal plants. Instead of pulling other developing nations up to help them achieve China’s own domestic standards, China is treating many nations as a dumping ground, offloading outdated coal generation technologies that are too inefficient and pollution-intensive to use at home.

Chinese officials and development experts often argue that China is providing the cheapest alternatives because that is what lower-income nations want. That approach is short-sighted. It fails to account for the mid- and longer-term costs associated with sub-standard projects. Indonesia’s experience should serve as a warning for Beijing. After purchasing a first wave of sub-critical coal plants from China, Indonesia is now looking to other nations to support future energy infrastructure expansion. If China does not change its approach, negative impacts from the first wave of Belt and Road energy investments could outweigh the positive impacts. That could be particularly consequential in Southeast Asia, which is one of the fastest-growing energy consuming regions in the world and a key focus for China’s Belt and Road Initiative. This paper will describe China’s current approach to energy development in Southeast Asia and the downside risks associated with that approach.

China’s Approach to Coal-Fired Power Development

Domestically, China is transitioning its coal-fired power fleet from older, high-polluting subcritical coal-fired power units to newer and cleaner supercritical and ultra-supercritical units (Hart, Bassett, and Johnson 2017). Chinese regulators are using a mix of efficiency standards, emission regulations, and mandatory subcritical plant retirements to drive this shift. The regulatory measures are impressive. By 2020, all existing Chinese coal-fired power units must meet an efficiency standard of 310 gce per kilowatt-hour. To put that in comparison with the U.S. coal fleet: no existing U.S. coal-fired power unit is performing at those efficiency levels today (Hart, Bassett, and Johnson 2017).

China’s domestic coal transition is making the nation a world leader in supercritical and ultra-supercritical coal-fired power technologies. If China leverages its growing international role to bring those technologies to other nations, that could help other nations avoid building out more pollution- and carbon-intensive coal plants. China is particularly active in developing nations that are unable to meet the high project standards required to obtain financing from the World Bank and other western-led development banks (IMF 2018). Many of those lower-income nations are currently experiencing the rapid growth rates associated with early-stage economic development and, in order to fuel that growth, rapid energy infrastructure expansion. The generation technologies these nations choose will have an outsized impact on their local environmental conditions and the global climate for decades to come. China is well-placed to push that expansion in a sustainable direction.

Unfortunately, Beijing is thus far taking a different approach. When Chinese banks and firms go abroad, they tend to follow a bifurcated strategy: they bring cutting-edge energy technologies to developed markets and cheap, outdated technologies to developing markets. In the energy sector, that strategy risks saddling developing regions with severe local environmental pollution and skyrocketing carbon emissions. As Beijing tightens China’s domestic coal-fired power standards, Chinese firms can no longer build subcritical plants at home so many of them are sending those technologies abroad. In some cases Chinese firms are actually dismantling outdated coal-fired power plants and exporting them to developing nations. At a global level, if China continues to export outdated energy technologies that will make it harder to slow and reduce global climate change.

Southeast Asia’s Energy Expansion

Southeast Asia is one of the fastest-growing energy consumption regions in the world and is launching a major energy infrastructure boom. The region’s per capita energy use is still relatively low, at 0.13 tons of oil equivalent as of 2013. That consumption rate is expected to more than double by 2035 as economic development expands energy access and consumption ability across the region (ASEAN Center for Energy 2015). Population is also projected to grow rapidly and that will further drive electricity consumption growth. Between 2015 and 2040, the region’s overall energy demand is projected to grow 80 percent and power consumption is projected to triple. By 2025, the region is expected to add around $1.5 trillion in new energy infrastructure to supply its growing demand. Energy technology choices made during this massive infrastructure expansion will have an outsized impact on the region’s energy efficiency, sustainability, and climate emissions for decades to come.

As of 2013, the ASEAN region generates 821 TWh of electricity, of which natural gas accounts for 44 percent, coal 31.5 percent, and oil 4.16 percent (ASEAN Center for Energy 2015). Although natural gas dominates in installed capacity, the region is rapidly shifting toward coal, and coal already outpaces natural gas in new-builds. By 2035, coal is projected to account for around 55 percent of the region’s electricity generation (accounting for 30 percent of total global coal growth through 2035). By 2040, the region will likely consume as much coal as India today. As a result, the region’s energy-related carbon dioxide emissions are projected to double by 2035.

Renewable energy is also growing – as of 2013, installed renewable energy generation capacity totaled 45.7 GW and accounted for around 21 percent of total electricity generation. All ASEAN nations have renewable energy targets and policies, but coal still enjoys substantial policy support, partly because the region is rich in coal resources and partly because coal production interests heavily influence energy policy in many ASEAN nations.

China’s Role in Southeast Asia’s Sub-Critical Coal Expansion

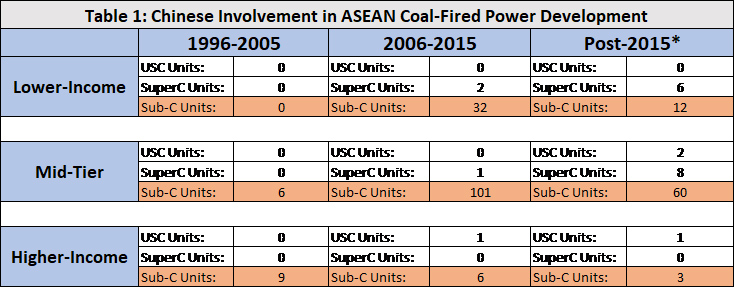

Below, Table 1 tallies the number of coal-fired power units Chinese companies are supporting across all three Southeast Asian income tiers and over time. It is not surprising to see subcritical plants in the 1996-2005 time-frame because cleaner plants were less available. However, the post-2015 project pipeline is a concern, because those plants are under construction in an era when the Southeast Asian region is undergoing a major energy boom, cleaner options are more available, and Beijing is banning sub-critical technologies domestically.

Chinese firms are beginning to bring some cleaner projects to the region. As of 2016, Chinese companies had participated in 4 cleaner-coal projects, with another 17 in the pipeline. However, China is much more active on the subcritical side, with 154 units completed and another 75 in pipeline as of 2016.

Source: Center for American Progress analysis using data from S&P Global Platts.

Note: The “post-2015” category includes plants operating in 2016 and early 2017 but is mostly composed of plants under construction or planned for 2017-2021. This chart does not include plants that were retired or canceled before 2016.

Chinese officials and development experts routinely claim Chinese firms are simply providing what the recipient nations can afford and once those nations can afford cleaner technologies, Chinese companies will be delighted to provide them. However, the reality is that other major development funders are already building cleaner projects in nations where China is still actively promoting subcritical coal. For example, Japan currently has sixteen ultra-supercritical coal-fired power projects underway in the region while China has only three.

Lessons from Indonesia

Indonesian officials and energy experts admit that the Chinese firms who provided subcritical coal-fired power units for the 10,000 MW program were delivering what Indonesia was asking for, which was a low-cost solution. Indonesian officials report that Japanese and South Korean firms tend to walk away and refuse to build plants at ultra-low price points, but Chinese firms are more likely to try to make things work, which sometimes brings bad consequences.

Today, Indonesia recognizes that subcritical coal technology is a bad investment, particularly when subcritical plants are manufactured using out-of-date and/or second-hand components. Under current Indonesian President Joko Widodo, Jakarta has announced a new planned 35,000 MW expansion in generation capacity, which is supposed to include cleaner coal technology as well as renewables. In theory, the 35,000 MW expansion would be great opportunity to bring in China’s more cutting-edge technology solutions. In reality, however, recent field interviews suggest that Indonesian officials are largely avoiding Chinese technology in this round due to the government’s experience with previous Chinese-financed and Chinese-manufactured subcritical coal-fired power expansions. Instead, local officials report that they are looking primarily to Japan and South Korea for cleaner alternatives.

The Indonesian case suggests that when China provides low-cost, high-emission systems to developing markets, medium-to-longer term performance or sustainability problems may not only affect those nations’ climate and emission trajectories but also impact their openness to choosing Chinese technologies as they move up the economic development ladder.

Chinese officials are assuming that, by providing low-cost solutions today, they will have an opportunity to provide cleaner, higher-performing solutions down the road. In reality, negative experiences with first-round Chinese development projects could turn recipient nations away from future Chinese projects. If so, that trend has the potential to undermine China’s position as a low-emission technology provider across the region, despite the fact that China has already developed impressive technology innovations at home and has much to offer, not only in the coal sector but also in renewable energy technology.

Going Forward: Can China Avoid Building a Dirty Belt and Road?

There are two potential pathways for Chinese involvement in Southeast Asia’s energy infrastructure expansion going forward. China could continue with the status quo approach, pushing low-standard technologies in less-developed regions and reserving China’s most innovative energy technologies for higher-income nations that can afford to pay higher up-front project costs. The backlash that China’s subcritical coal projects are already generating across Indonesia suggests that, if China pursues this approach, it will become a less attractive development partner over time. Once recipient nations gain the ability to pay for higher-standard projects, they may follow Indonesia’s example and turn to other nations instead of seeking to upgrade with a new generation of Chinese products. That would be particularly unfortunate in the coal sector because, as China transitions its domestic energy sector toward cleaner coal generation, it increasingly has cutting-edge technology and operational knowledge that could benefit Southeast Asian nations.

Alternatively, China could change its approach and seek to leverage the Belt and Road Initiative and other state-supported programs to help developing nations leapfrog up to the same standards China is implementing domestically. That would require a mix of capacity building—to help recipient nations understand the full array of innovative technologies available and how to deploy them in their own markets—as well as innovative financing to help those nations meet the higher up-front costs associated with cleaner projects. This approach would shift the role China is playing as an international infrastructure developer, providing increasing rather than decreasing opportunities for Chinese investment over time. This approach would also provide broad regional and global benefits, particularly on the climate front.

Author’s Biography

Melanie Hart serves as senior fellow and China policy director at the Center for American Progress (CAP), a leading American think tank based in Washington, DC. She is responsible for formulating CAP policy proposals on China and US-China relations and leading CAP efforts to promote those proposals with political leaders in the United States and Asia. She founded and leads multiple US-China track II dialogue programs at the Center and frequently advises senior U.S. political leaders on China policy issues. Hart also serves as a Senior Advisor on China to The Scowcroft Group, a premier international business advisory firm.

Center for China Studies

Rising China and New Civilization in the Asia-Pacific

![[ADRN Working Paper] Horizontal Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅰ)](/data/bbs/eng_workingpaper/20240305162413775004648(1).jpg)

Working Paper

[ADRN Working Paper] Horizontal Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅰ)

Asia Democracy Research Network | 2019-05-16