[Asia Democracy Issue Briefing] Party Polarization without Party Sorting in South Korea: Centrist Voters in Drift

Democracy Cooperation | Commentary·Issue Briefing | 2020-09-11

Jung Kim

Editor's Note

Since democratization, South Korean party politics has been featured by increasing party polarization and incomplete party sorting. In this issue briefing, Prof. Jung Kim examines several factors that have led to party polarization and incomplete party sorting in the country’s politics. Prof. Kim argues that under the two-and-a-half party system, political representation has been unequal, as it over-represents progressive and conservative voters while under-representing centrists, thereby increasing polarization between progressive and conservative parties. At the same time, Prof. Kim argues that the number of centrist voters who do not fall under the ideological distributions of the major parties remains significant, which indicates that party polarization has not been corresponding with party sorting, leaving centrist voters in drift.

This essay seeks to illustrate party politics in South Korea that has unfolded since its democratic transition that took place in 1987. For starters, it argues that South Korea’s party system has brought about an asymmetric structure of political representation that over-represents progressive and conservative voters while under-representing centrist voters. It also claims that unequal political representation has engendered party polarization in South Korean politics. It further argues that party sorting has been incomplete whereby parties have difficulty shaping political issues in a partisan way to exploit their electoral advantages. Increasing party polarization and incomplete party sorting capture the evolving nature of party politics in South Korea since its democratic transition.

Asymmetric Political Representation

South Korea’s party politics has been gradually stabilized since its democratic transition, producing a two-and-a-half party system. The average number of legislative parties has changed from 2.77 in the 1990s to 2.63 in the 2000s, and 2.41 in the 2010s This two-and-a-half party system consists of ‘two’ parties that have managed to maintain the continuity of partisan brands as progressive and conservative respectively, and ‘half’ parties that have inevitably faced the interruption of partisan brand as centrist. Progressives have altered their party labels from Peace Democratic Party (1987-1991) to Democratic Party (1991-1995), National Congress for New Politics (1995-2000), Millennium Democratic Party (2000-2005), Uri Party (2003-2007), Unified Democratic Party (2007-2011), Democratic Unified Party (2011-2014), and Democratic Party (since 2014). Likewise, party labels for conservatives have changed from Liberal Democratic Party (1990-1995) to New Korea Party (1995-1997), Grand Korea Party (1997-2012), Saenuri Party (2012-2017), Liberty Korea Party (2017-2020), and United Future Party (Since 2020). Despite recurrent relabeling, South Korea’s progressive and conservative voters have acknowledged the succession of partisan brands from one party to another, attaching their partisan loyalty, however tenuous it might be, to the ‘two’ parties.

For South Korea’s centrist voters, no such continuity of partisan brand has been established from United People’s Party (1992-1995) to United Liberal Democrats (1995-2006), Creative Korea Party (2007-2012), People’s Party (2016-2018), and Bareun Party (2017-2018), simply because these parties were not successor parties one another. Consequently, centrist voters have found themselves in a situation in which their efforts to attach partisan loyalty to centrist parties are destined to be interrupted. The National Assembly members are selected by the majoritarian mixed-member electoral system consisting of 85% of seats from single-member districts and 15% from proportional representation lists, which institutionally favors two larger parties at the cost of smaller parties. Under such a ‘winner-take-all’ systemic pressure, centrist voters, which consist of more than 40% of the electorate, according to a recent opinion survey, tend to abstain or to be compelled to cast their ballots for one of the larger parties in order not to waste their votes. Centrist voters with the weak partisan attachment are less likely to have strong incentive to engage in political life. In fact, a study shows that voters with strong partisan identities are more likely to vote than voters with weak partisan identities during recent presidential elections in South Korea.

In sum, South Korea’s two-and-a-half party system has brought about an asymmetric political representation, in which voters with strong partisanship tend to be over-represented, while voters with weak partisanship tend to be under-represented. This is why political scientist Jang Jip Choi claims that the “greatest cleavage in contemporary Korean politics is between a representation system with no social foundation and the nonvoters who resist and cannot gain representation through that system.”

Increasing Party Polarization

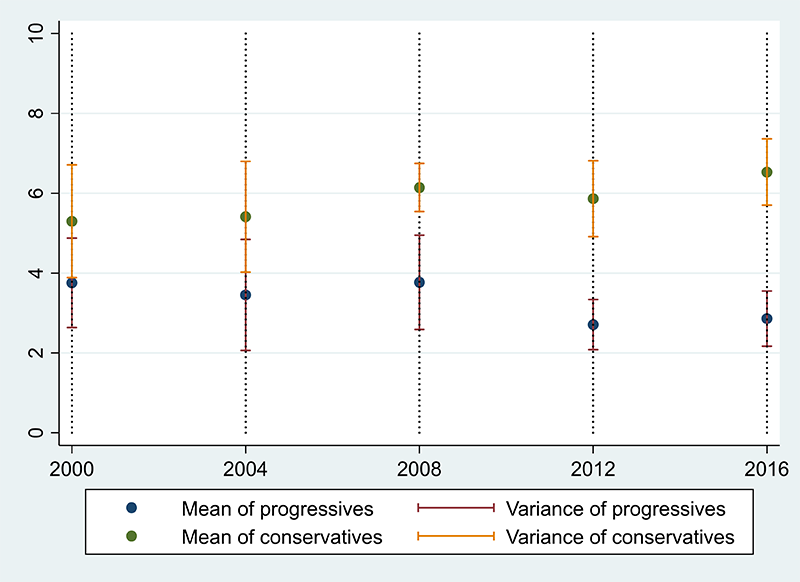

The asymmetric structure of political representation, in which progressive and conservative voters are more actively involved in politics in general and elections in particular than centrist voters are, has made electoral strategies of two large parties depart from the median voter theorem and resort to strategic extremism. To put it differently, the two large parties are more likely to rely on ‘mobilization’ to push for voters with strong partisan identities who will vote for them to go to the polls rather than ‘persuasion’ to convince voters with weak partisan identities who are more predisposed against, but not adamantly opposed to, them to change their opinion. Once the two parties decide to abjure ‘persuasion’ and to embrace ‘mobilization’ as their dominant electoral strategy, then party polarization would kick in. Figure 1 demonstrates this logic of party polarization with the disappearing centrists.

Note: Author’s representation based on the data extracted from Institute of Korean Political Studies,

Seoul National University http://www.ikps.or.kr/board03/list.asp (accessed on August 25, 2020)

Figure 1 represents ideological means and variances of the National Assembly members from progressive and conservative parties from 2000 to 2016. The distance of ideological means between the two parties has clearly inclined from 1.54 in 2000 to 1.96 in 2004, 2.37 in 2008, 3.15 in 2012, and 3.67 in 2016. The average ideological variances that represent the degree of partisan coherence of each party has steadily declined from 1.12 in 2000 to 0.69 in 2016 for progressives and from 1.41 in 2000 to 0.83 in 2016 for conservatives. It is important to note that there were overlapping areas between progressive and conservative parties in the 2000s, in which bipartisan cooperation was expected. Such overlapping areas to expect bipartisan cooperation no longer existed in the 2010s, which indicates that party polarization deepened and widened with increasing intra-party homogeneity and inter-party heterogeneity. In other words, it implies that centrist legislators have disappeared in the National Assembly of South Korea.

Incomplete Party Sorting

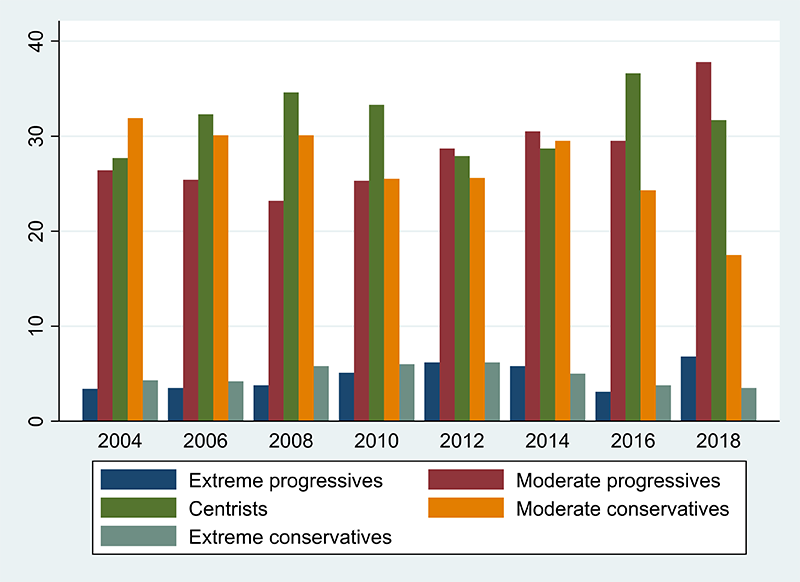

To complete the picture of South Korea’s party politics, it is essential to note that party polarization resulted from the misalignment of representation between politicians and voters. In other words, as ideological distributions of parties have continuously lost correspondence to those of voters over time, progressive and conservative parties have become more distant from each other, leaving the voice of centrist voters unheard. Figure 2 illustrates that such representation misalignment captures part of South Korea’s party politics.

Note: Author’s representation based on the data extracted from Korea Social Science Data Archive https://kossda.snu.ac.kr/ (accessed on August 25, 2020)

In Figure 2, the number of voters who self-identify themselves as centrists is significant among South Korea’s electorate in the 2000s and the 2010s. Specifically, the average share of centrist voters is 32.0 percent in the 2000s and 31.2 percent in the 2010s. The stability of centrist voters in size is remarkable, considering the changes in the average share of moderate progressive voters up from 25.1 percent in the 2000s to 31.6 percent in the 2010s and those of moderate conservative voters down from 29.4 percent in the 2000s to 24.2 percent in the 2010s. In this respect, it is not unreasonable to claim that unlike increasing party polarization, there has been little progress on party sorting – migrating centrists toward progressive or conservative parties – in South Korea.

The finding that the ‘unimodal’ ideological distribution of voters has been at odds with the ‘bimodal’ ideological distribution of parties strongly suggests that party sorting has been incomplete in the country in the sense that centrifugal forces emanated from party polarization are not strong enough to bring about the corresponding party sorting. To simply put, while the two large parties might have become more polarized in the political marketplace, they have not succeeded in polarizing the electorate at large. Compared with the United States where voters’ social identities grow increasingly party-linked and parties become more influential in political decision-making due to escalating party polarization and party sorting, the effect of partisanship on policymaking is less pronounced, which makes voters more open to alternative policy ideas in South Korea.

In conclusion, although the combination of increasing party polarization and incomplete party sorting is far from the best case scenario that helps South Korea’s democracy work, it at least enables the democracy to avoid the worst case scenario that falls victim to the partisan divide in society at large.■

■ Jung Kim is currently an Assistant Professor at the University of North Korean Studies, South Korea. He teaches courses on International Relations in East Asia and Political Economy of the Two Koreas, among others. Prior to this, from 2009-2015, he was a Lecturer at the Underwood International College and Graduate School of International Studies at Yonsei University. During this time, Mr. Kim was also a Chief Researcher at The East Asia Institute. He pursued his Bachelors and Masters in Political Science at Korea University and went on the pursue his Ph.D. at Yale University. His research interests include Comparative Politics and International Relations in East Asia.

■ Typeset by Eunji Lee, Research Associate/Project Manager

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 207) | ejlee@eai.or.kr

The East Asia Institute takes no institutional position on policy issues and has no affiliation with the Korean government. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in its publications are the sole responsibility of the author or authors.

Center for Democracy Cooperation

South Korea Democracy Storytelling

Democracy Cooperation

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20240419123938102197065(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections

Niranjan Sahoo | 2020-09-11

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2024032815145548472837(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?

Ken Godfrey | 2020-09-11