[Asia Democracy Issue Briefing] The Role of Civil Society in South Korean Democracy: Liberal Legacy and Its Pitfalls

Democracy Cooperation | Commentary·Issue Briefing | 2020-08-21

Jai Kwan Jung

Editor's Note

South Korea is regarded as an exemplary case of democratic transition amongst third-wave democracies in Asia. In this issue briefing, Prof. Jai Kwan Jung examines the trajectory of democratic development in South Korea by focusing on the role of civil society in the transition to and the consolidation of democracy in the country. While civil society mainly constituted a ‘contentious’ civil society against authoritarianism during democratic transition, it has transformed itself to a diversified and peaceful civil society since then. Nonetheless, Prof. Jung argues that while strong civil society is a historic legacy of the country’s democratization, there are also pitfalls: when strong civil society is combined with weak political parties and divided along the ideological spectrum, it can turn into a liability for democracy by undermining institutional politics and fuelling populism.

South Korea’s Democratic Development in Comparison

South Korea is one of the most successful cases among 91 cases of democratic transitions since the third-wave of democratization. Using the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) data, Mainwaring and Bizzarro (2019) categorize the outcomes of those 91 cases that transitioned to democracy from 1974 to 2012 as democratic breakdown, erosion, stagnation, and advance. While 23 of 91 cases (25.3%) are classified as democratic advance, only 8 cases (8.8%) have reached the level of liberal democracy. South Korea is one of those 8 successful cases and the second-best case, following Portugal, which has most improved the quality of democracy from the year of regime transition.

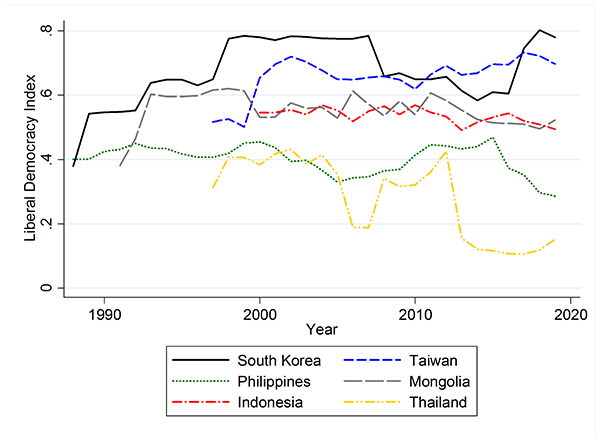

Figure 1 compares South Korea’s post-transition trajectory with five other third-wave democracies in Asia – Taiwan, Mongolia, Philippines, Indonesia, and Thailand. Since its transition to democracy in 1987, South Korea’s quality of democracy consistently increased and reached the level of liberal democracy (i.e., 0.7 in the Liberal Democracy Index) in 1998, when the Kim Dae-jung government was inaugurated. But South Korean trajectory of democratic development is not unilinear. The liberal principles of democracy came to decay substantively from 2008 to 2016 during two conservative governments. This downward trend was most pronounced in 2014 when the Park Geun-hye government faced a governing crisis after the Sewol ferry disaster, in which 304 people, including 250 high-school students on their field trip to Jeju Island, were drowned. This governing crisis was further fueled by the Park Geun-hye and Choi Soon-sil corruption scandal and led to the massive wave of candlelight protests in 2016. A total of 17 million people participated in 6-month long Saturday protests from October 2016 to April 2017. It was a historic moment in South Korea, not just because of the unprecedented size and peacefulness of mass mobilization. For the first time in the history of Korean democracy, the 2016-17 candlelight protests resulted in the impeachment of an incumbent president through due constitutional procedures. The candlelight protests seem to have saved Korean democracy, since its liberal democracy score increased and passed again the cut-point of 0.7 in 2017.

If we look at the post-transition trajectories of other Asian democracies in Figure 1, Taiwan and Mongolia can be also classified as democratic advance. Yet in terms of the level of liberal democracy, only Taiwan is comparable with South Korea. Mongolia’s quality of democracy has been closer to Indonesia, which shows a pattern of stagnation since the transition to democracy. Philippines and Thailand clearly show the vulnerability of third-wave democracies. These two new democracies experienced democratic breakdown in 2004 and 2006 respectively, as 34 of 91 third-wave democracies have done so (37.4%).

Contentious Civil Society and Its Diversification after Democratic Transition

How can we understand South Korea’s successful post-transition trajectory of democratic development? There are many factors that can affect post-transition trajectories in general. One particular factor in South Korea is the role of civil society in the transition to and the consolidation of democracy. Conceptually, democracy puts the state and civil society in a horizontal relationship, while authoritarianism uses the state’s power to control or repress civil society in a vertical manner. As civil society tends to be contentious, if not co-opted, in authoritarianism in transforming the vertical relationship with the state to a horizontal one, it can play a critical role in the transition to democracy. Theoretically, civil society mobilization for democracy can compel authoritarian elites to stop defending the old order and signal the collapse of authoritarian rule by creating a united force for democratic reforms. If civil society successfully mobilized popular pressures for democracy and influenced the bargaining between ruling elites and opposition leaders during democratic transition, it would have an enduring effect in the subsequent period of democratic development. This is because the collective experience of making popular pressures for democracy can shape the public perception about the role of civil society and the significance of citizens’ direct action in advancing democracy. Another reason is that the unified pro-democracy coalition may evolve into a variety of civil society groups in widely open and free political opportunities after democratization. Those various groups constitute a vibrant civil society, which is a key component of advanced democracy.

From the Syngman Rhee government in the 1950s to the Park Chung-hee regime in the 60s and 70s, South Korean civil society had actively resisted authoritarianism. The April 19 Revolution in 1960 toppled the Syngman Rhee government. Liberal intellectuals, journalists, lawyers, pastors and priests as well as college students constituted a contentious civil society, which is called chaeya, and mobilized democratic opposition against the Park Chung-hee regime. This contentious civil society formed a unified democratic coalition along with opposition political elites during the Chun Doo-hwan military dictatorship in the 1980s and eventually brought about the liberalization of the authoritarian rule. After the transition to democracy, the contentious civil society has been diversified into various sectoral movements (e.g., the women’s movement, the environmental movement, etc.) and civic organizations (e.g., the People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy, the Citizens’ Coalition for Economic Justice, etc.). This historic change can be understood as a transformation of South Korean civil society from a contentious and often militant to a varied and peaceful one.

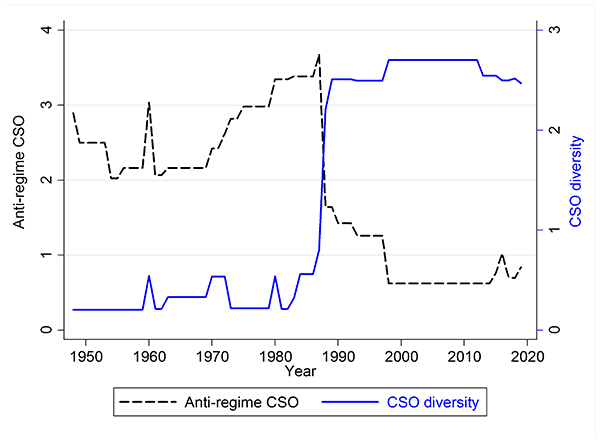

Figure 2 clearly shows the historical transformation of South Korean civil society in terms of its nature and constitution from 1948 to 2019. The V-Dem data include several indicators for civil society organizations (CSOs). By using two of those CSO indicators, Figure 2 presents a historical pattern of change in South Korean civil society. Prior to the transition to democracy, the dominant nature of South Korean CSOs had been “anti-regime” movements, which means that the main purpose and activities of CSOs were to change the political system from authoritarian to a democratic one. This anti-regime nature of South Korean CSOs had increased from the Syngman Rhee government (the average of anti-regime CSO score on the left Y-axis was 2.39) to the Park Chung-hee era (2.53) to the Chun Doo-hwan regime (3.41). After democratization, it dropped substantially. The average anti-regime CSO score became 1.38 for the first 10 years of democratization and 0.66 since 1998. To the contrary, South Korean CSOs became highly diversified after the transition to democracy. Before 1987, the average score for CSO diversity on the right Y-axis was 0.31, which means that most South Korean CSOs used to be state-sponsored and not voluntary with the smaller number of voluntary and anti-regime movement organizations. But since 1988, it jumped into 2.59, which is fairly a high degree of diversification of voluntary CSOs. In essence, the democratic transition in 1987 fundamentally changed the dominant feature and diversity of South Korean CSOs, as we can see vividly in Figure 2.

Pitfalls of Strong Civil Society

South Korea’s vibrant civil society is a legacy of the democratization movement during the authoritarian period. This historic legacy is an important asset and has worked well for democratic development so far. But strong civil society is not always good for democracy, especially if it is divided by a politicized social cleavage and when there is a fierce competition for mass mobilization along that cleavage line. In this respect, there are two pitfalls in the foreseeable future of South Korean democracy.

First, South Korea’s strong civil society has been combined with weak political parties. This combination of strong civil society and weak parties has led to under-development of democratic institutions, such as party and electoral systems as well as institutional politics often swayed by civil society voices and interests. It has in turn generated a serious concern about the stability of South Korean democracy. One particular problem is so-called “emperor-like presidentialism.” If a president mainly relies on vocal demands of strong civil society in his/her decision-making and is unchecked by the under-developed legislative and judicial bodies of the government, presidential power can be more overly concentrated than it is now and a populist rule might be a real possibility in the near future.

Second, South Korean civil society has increasingly mobilized ordinary people along the left-right ideological cleavage. It will be harmful for the future of South Korean democracy, because it can exacerbate the governability problem of its democracy. The 2016-17 candlelight protests and the impeachment of Park Geun-hye has brought about a right-wing counter-movement in the form of Taegukgi (national flag) protests. This ideological polarization in civil society became highly conspicuous in the fall of 2019 when the appointment of Cho Kuk as Minister of Justice brought about the months of street protests by both anti- and pro-Cho citizens. Massive civil society mobilization along the ideological divide has undermined South Korea’s institutional politics further, as major parties and political elites were captured by competing and even hostile claims of the divided civil society. It has also made scholars and pundits worry about the potential instability of South Korean democracy.

In conclusion, South Korea’s strong civil society can turn into a liability for democracy under certain conditions. If it is sharply divided along the ideological spectrum while undermining institutional politics, it can be a fertile ground for populism. South Korean civic groups and political elites should be aware of this caveat and reduce the likelihood of the emergence of populist politics. In order to do so, they need to establish a healthy relationship between parties and civil society by seeking a balance between institutional and non-institutional politics of democracy.

■ Jai Kwan Jung (Ph.D., Cornell University) is Professor in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Korea University. His research interests include social movements and contentious politics, political conflict and violence, and comparative democratization.

■Typeset by Eunji Lee, Research Associate/Project Manager

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 207) ejlee@eai.or.kr

The East Asia Institute takes no institutional position on policy issues and has no affiliation with the Korean government. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in its publications are the sole responsibility of the author or authors.

Center for Democracy Cooperation

South Korea Democracy Storytelling

Democracy Cooperation

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/20240419123938102197065(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Decoding India’s 2024 National Elections

Niranjan Sahoo | 2020-08-21

![[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?](/data/bbs/eng_issuebriefing/2024032815145548472837(1).jpg)

Commentary·Issue Briefing

[ADRN Issue Briefing] Inside the Summit for Democracy: What’s Next?

Ken Godfrey | 2020-08-21