Editor's Note

Thailand's general election was held on March 24, 2019. Its new electoral rules based on the 2017 constitution remain controversial due to several political issues related to civic trust and majority representation. According to Thawilwadee Bureekul, Director of Research and Development Office at King Prajadhipok’s Institute (KPI), the constitutional amendment has enabled the Thai military to exert stronger influence over the National Assembly. KPI's public opinion polls, administered before and after the 2019 general election, also show that the level of public trust in the Thailand Election Commission has declined consecutively since 2016. On the basis of these observations, Dr. Bureekul argues that "public bitterness with the new electoral process is likely to grow throughout the coming years" and requires government attention.

Introduction

Thailand’s general election held on March 24, 2019 is representative of an ongoing battle between its pro-military and pro-democratic forces, and indicative of yet another culmination to the democratic transition which had preceded the 2014 military coup. While the election rallied 51,239,638 eligible voters and the voter turnout reached 74.69 percent, its modified electoral process on the basis of the 2017 constitution has been a subject of critical debate among democratic scholars and policymakers. With alleged voting irregularities and delays in the release of official results, Thailand’s constitutional amendment raises several important questions. This paper, in particular, expands on whether the changes in the electoral process inflicted by the 2017 constitution enable the Thai public to properly elect Members of Parliament (PM) and the Prime Minister (PM) based on their majority support. It also supplements the overall discussion with findings from public surveys conducted by King Prajadhipok’s Institute before and after the 2019 general election in Thailand.

Do the Elected Members Represent Majority Public Support?

The 2019 general election in Thailand was the first of its kind since the promulgation of the 2017 constitution. Unlike its predecessor from 1997, the 2017 constitution introduces a new voting system where instead of marking two parallel ballots—one for the constituency Member of Parliament (MP) and another for the political party—voters are asked to cast a “mixed-member apportionment” with a single vote for both the candidate and the party.

The constitutional amendment has consequently impacted the proportion of seats allocated to different political parties within the National Assembly. From a total of 500 seats within the Lower House, 350 are determined directly by a casting of vote while the remaining 150 are allocated to the respective political parties of the elected MPs in proportion to their nationwide number of votes. Without separate ballots being cast for party-list seats, the amendment hence provides many smaller parties political advantage while limiting majoritarian parties with higher general public support from gaining access to the reserved 150 seats.

These changes in the electoral process, however, have led to several controversie surrounding the 2019 general election. Firstly, compared to prior elections, the Election Commission (EC) had more difficulties in reviewing and tabulating the votes because they had to determine whether the 350 constituencies complied with the newly adopted constitution. Based on the constituency count, the EC then calculated the 150 seats based on Article 128 of the 2018 Organic Act on the Election of the House of Representatives, whose methods bear uncertainties (Allen Hicken 2020). Official results were finally announced on May 8—45 days following the election—after which the general public still held speculations as to whether the results displayed accurate representation of their votes.

Secondly, due to how the 150 seats were allocated, a coalition government comprised of more than 20 smaller parties was formed whereas other larger parties did not receive as many seats correspondent to their greater and wider public support. For instance, the Pheu Thai party of former PM Thaksin Shinawatra was deemed ineligible for any of the 150 seats since it had won more constituency seats than those available for the party-list. Another example addresses the anti-military and relatively newly formed Future Forward Party (FFP), which was on its track to become Thailand’s third largest political party with 5.3 million vote counts. Unfortunately, however, its leader Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit was disqualified from the elections due to media ownership allegations submitted by the EC. Critics therefore continue to question the implications behind the new electoral rules and whether they have been implemented to prevent larger sized parties from potentially threatening the military’s political leverage.

Another issue that stems from the 2017 Constitution is the way in which the Prime Minister (PM) was elected. According to the new constitution, the PM is elected by the combined National Assembly, which includes both the Upper and Lower Houses. However, the respective electoral amendments also dictate that the 250 senators who comprise the Upper house be appointed by the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) which lies largely under the control of Thailand’s military and the royal family. Such stipulation hence provides 250 non-elected members to exercise significant influence over the election of the Prime Minister (PM), since only 126 Lower House members are needed to determine majority support. With the Lower House comprised of around 20 smaller parties and the Upper House staffed with senators appointed by the military, the pro-military General Prayut Chan-o-cha was elected as PM as a result of the 2019 general election.

Public Perception of the 2019 General Election

As aforementioned, the 2019 general election calls for a critical review of Thailand’s 2017 constitution and its electoral process. These issues are also supplemented by the public’s relatively negative perception regarding the election. For instance, survey findings indicate that a higher number of citizens were skeptical of vote buying behavior occurring at the 2019 general election. According to the 2019 pre-election survey by the King Prajadhipok’s Institution (KPI), 35.3 percent of the respondents believed that there would be vote buying instances in the election compared to the 14.9 percent who responded that there would be no occurrence of such behavior. From the 35.3 percent who believed in vote buying behavior, 14.2 percent stated that it would increase with the coming election (King Prajadhipok’s Institution 2019).

Furthermore, according to the Election Commission, a total of 590 cases of citizen complaints were reported following the general election, from which 79 cases were submitted to the central EC office, 59 cases were reported in Bangkok, and 41 from Nakorn Rajsima. One of the major issues related to the complaints was the qualification of the MP candidates (Election Commission 2020). In fact, according to the 2020 survey by the KPI, 38 percent of the voters based their selection on the political party’s policy while 8.2 percent did so on the candidates’ reputation (King Prajadhipok’s Institution 2020). The results prompt further discussions on how to increase the qualifications of the candidates especially in the context of the new electoral process; without two separate ballots being cast for the constituency and the party, voters are now urged to make a strict selection between their preferred candidate and the political party of their choice.

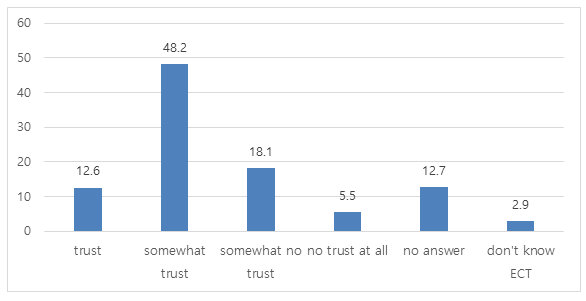

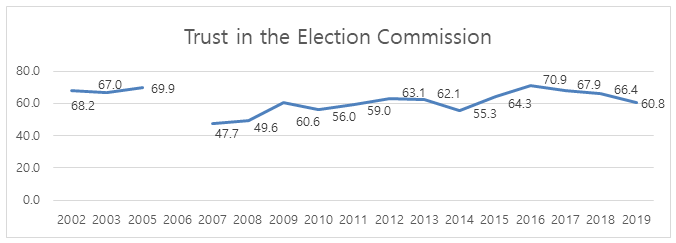

Finally, citizen trust in the Election Commission continues to show a decreasing trend since 2016. While over 60.8 percent of the respondents to KPI’s pre-election survey said that they trust Thailand’s Election Commission (Figure 1), this shows a 5.6 percent point decrease compared to 2018, and a 10.1 percent point fall since 2016 (Figure 2) (King Prajadhipok’s Institute 2019). The findings are also significant in that the citizen trust level showed a continuously rising trend prior to 2016, after which discussions related to the 2017 constitution gained more traction.

Figure 1: Trust in the Thailand Election Commission (2019)

Source: King Prajadhipok’s Institute (2019).

Figure 2: Trust in the Thailand Election Commission (2002-2019)

Source: King Prajadhipok’s Institute (2019).

Conclusion

The 2019 general election in Thailand has significantly altered the nation’s political landscape, which had been under democratic transition prior to the 2014 military coup. With the 2017 constitution as its backbone, the new electoral process has successfully borne a coalition government of smaller-sized parties in the Lower House of the National Assembly that do not possess the capacity to threaten the pro-military government. The government also has strong foundational support from its non-elected, appointed members of the Upper House, as well as from the newly elected pro-military Prime Minister.

In addition to international observers who have questioned the impartiality of the overall election, the Thai public portrays a negative public perception towards the 2019 general election. Most importantly, survey findings by the King Prajadhipok’s Institute before and after the election infer that civic trust in the Thailand Election Commission has been continuously decreasing since 2016 and 2017, which coincide with the promulgation of the 2017 constitution. Furthermore, the Thai public has been noting the lack of qualifications among the political candidates and has not been shy to file complaints regarding their relative inaptitude. Finally, because the 2017 constitution limits their votes to one ballot—for both the constituency and the party—public bitterness with the new electoral process is likely to grow throughout the coming years.

■Thawilwadee Bureekul is Director of Research and Development Office at King Prajadhipok’s Institute, Thailand. She used to serve as the National Reform Steering Committee, the National Reform Council and the Constitutional Drafting Assembly. Her current academic interest lies in the field of good governance and gender equity, such as participatory and gender responsive budgeting, preparation of action plan for leadership development and women’s participation in politics and decision-making, and gender-responsive local development planning and budgeting manual. She has been heavily dedicated to conducting research projects related to democracy, good governance, social quality, public participation, public policy, and voting behaviors. In 2015, she was awarded a prestigious award given to a woman with outstanding performance by the National Council of Women of Thailand. She also succeeded in proposing “Gender Responsive Budgeting” in Thai Constitution and was presented with the “Women of the Year 2018” award from the Association for the Promotion of the Status of Women accordingly.

The East Asia Institute takes no institutional position on policy issues and has no affiliation with the Korean government. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in its publications are the sole responsibility of the author or authors.

"IMG_3855" by Shafquat Towheed is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0