Ⅰ. Introduction

The findings from the East Asia Institute (EAI)’s 2024 East Asia Public Opinion Survey on Japan signal the onset of a new phase in South Korea (ROK)-Japan relations. Public sentiment with a positive impression of Japan has reached its highest level since the survey’s inception in 2013, while a negative impression has fallen to an all-time low. The public’s perception of improvement in bilateral relations is notably strong, and the level of trust in Japan has more than doubled compared to 2023’s. The ROK-Japan relationship is now decisively on a path of recovery.

The improvement in bilateral relations reflects broader patterns shaped by underlying structural dynamics. In the current geopolitical landscape, defined by the U.S.-China competition and North Korea’s ongoing nuclear and missile threats, the strategic importance and necessity of ROK-U.S.-Japan security cooperation continue to grow. Simultaneously, economic interdependence between South Korea and Japan has only deepened. Former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s attempts at supply chain decoupling in 2019—exemplified by Japan’s export controls on three key semiconductor materials and South Korea’s efforts to substitute imports—have largely been neutralized, underscoring the deep interdependence of the two countries’ economies. Furthermore, both nations increasingly share the values of freedom and democracy through the mutual consumption of popular culture and rising tourism. Cooperation between South Korea and Japan in security, economics, and culture is gaining momentum.

Nevertheless, this trend is not irreversible, as historical issues undeniably continue to present significant obstacles. Public opinion on the contentious historical disputes reveals contestation between political forces in both countries, each coalescing around specific beliefs, values, and goals. In South Korea, ideological and partisan division on key issues have intensified. Survey results show that public opinion is divided on major foreign policy agendas, such as the “third-party reimbursement” plan, the handling of the Sado Mine issue, and ROK-U.S.-Japan trilateral security cooperation.

The polarization of South Korea’s policy toward Japan undermines policy rationality and fosters the rise of extreme views. Rather than learning from past mistakes, there is a tendency to rely on partisan or ideological justifications, dismiss opposing opinions, and push forward policies unilaterally. This dynamic risks damaging South Korea’s international credibility and weakening its negotiating power vis-à-vis Japan. Looking ahead, a key challenge for South Korea’s Japan policy will be overcoming this polarization to ensure a more balanced and effective approach.

Ⅱ. Factors Contributing to Positive Perception of Japan

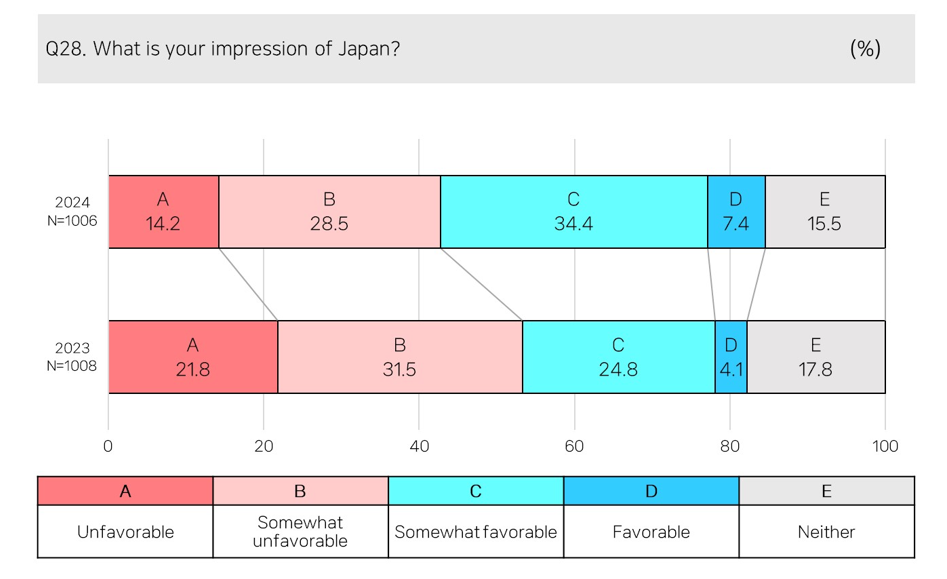

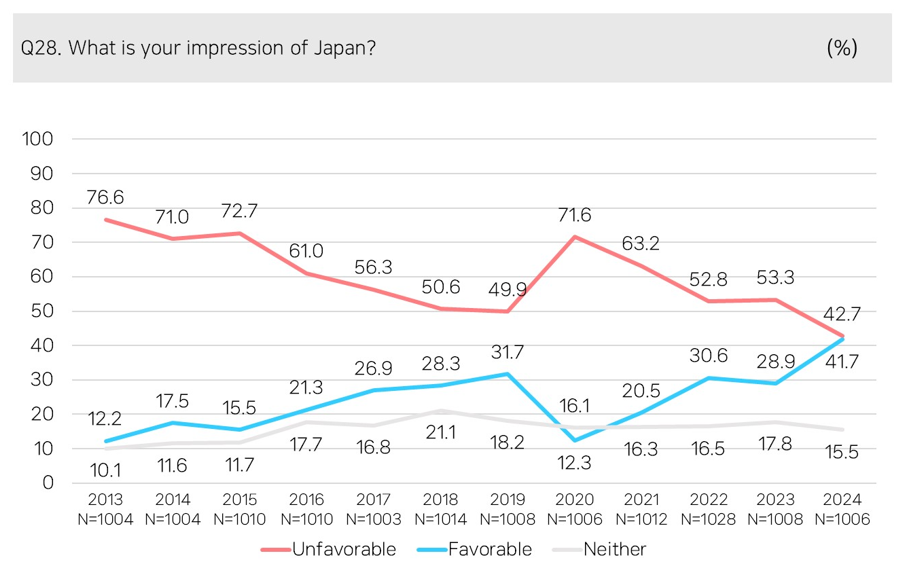

This year’s public survey reveals a significant rise in positive perceptions of Japan compared to last year. According to the results, 41.7% of respondents expressed favorable views (either positive or somewhat positive), while 42.7% held unfavorable views (either negative or somewhat negative), as shown in Figure 1. Positive sentiment increased by 12.9 percentage points, while negative sentiment decreased by 10.6 percentage points. This represents the highest level of positive perception and the lowest level of negative perception since the survey began in 2013 (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Public Perception of Japan

Figure 2: Trends in ROK Public Perception of Japan (2013-2024)

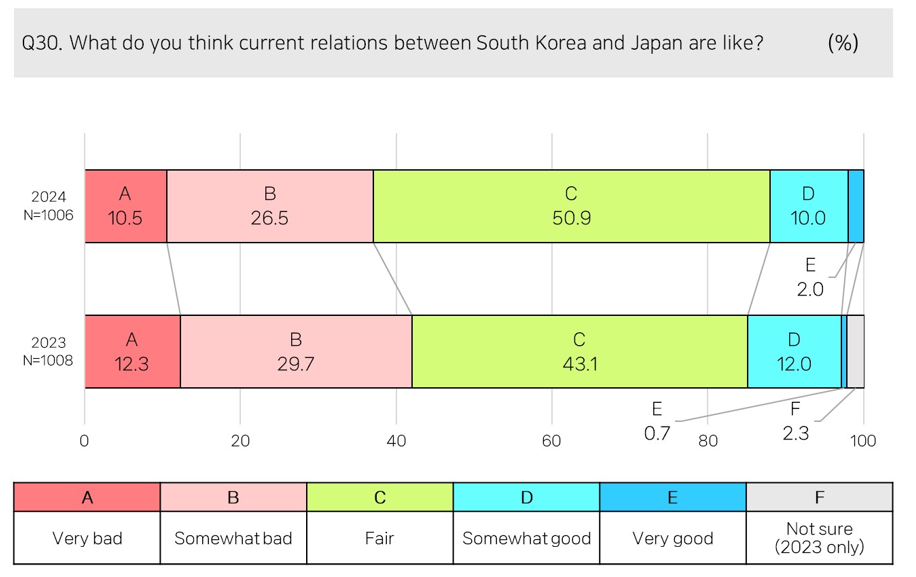

Positive perceptions of Japan have contributed to a more favorable assessment of the current ROK-Japan relationship. When asked about the state of bilateral relations, a majority (50.9%) described it as responded “fair,” while 37.1% rated it as “bad,” and 12.0% said it was “good” (Figure 3). While the percentage of those viewing the relationship as “good” remained relatively unchanged from the previous year (12.7%), there was a notable shift in other responses. The “bad” response decreased by 4.9 percentage points (from 42.0% to 37.1%), while the “fair” response increased by 7.8 percentage points (from 43.1% to 50.9%), suggesting a significant shift from negative to more neutral perceptions.

Figure 3: ROK-Japan Relations Today

Over the long term, positive perceptions of Japan have steadily increased since 2013, reaching an all-time high this year. This marks a recovery from a sharp decline in 2019, which was triggered by heightened ROK-Japan tensions. The upward trend in positive perceptions seems to have a structural foundation. As illustrated in Table 1 of the Appendix, key factors driving this rise include increased cultural exchanges through popular media, tourism, people-to-people interactions, and a growing sense of shared identity as democratic nations.

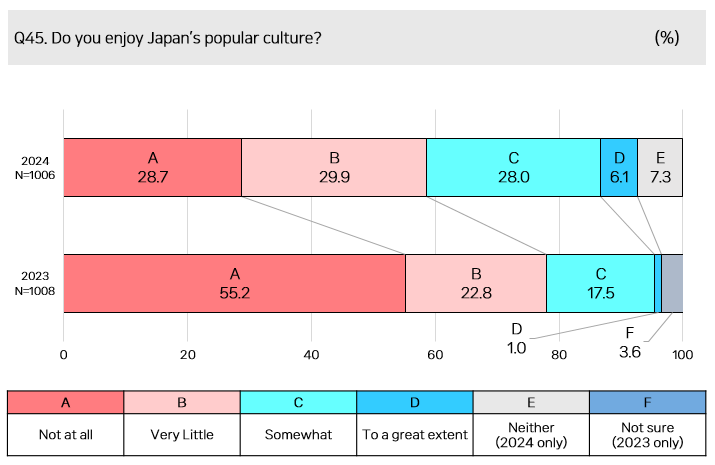

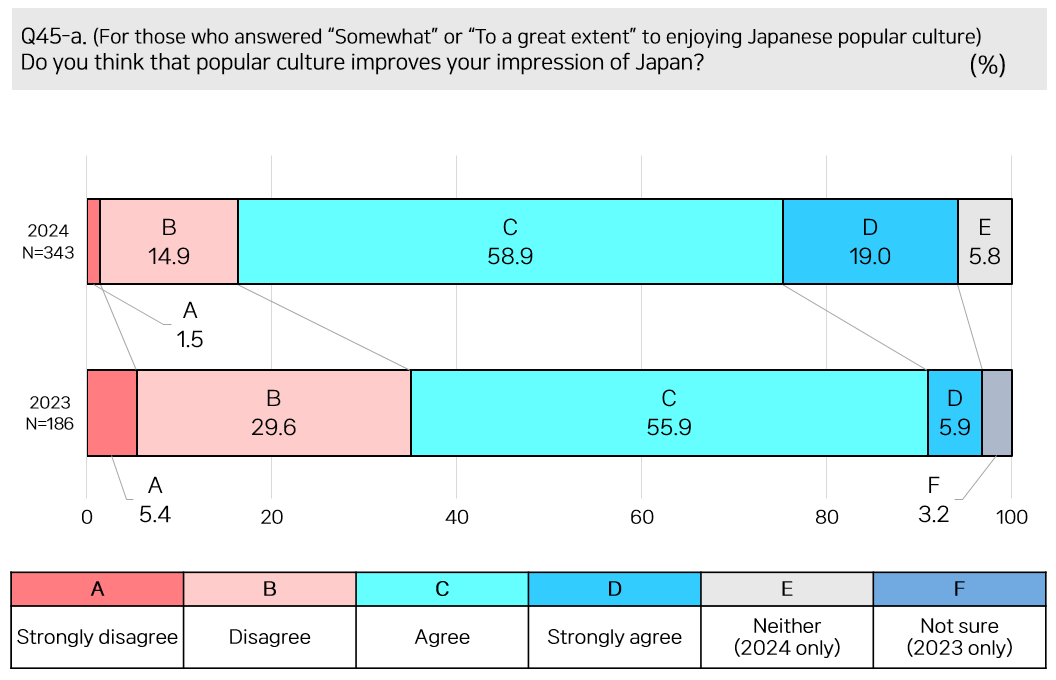

As Figure 4 illustrates, the number of Koreans consuming Japanese popular culture, such as anime, manga, and novels, has been steadily increasing. Additionally, more Koreans are experiencing Japan firsthand, with nearly 6.96 million visiting in 2023 and 5.19 million visiting between January and July 2024 alone. Among these visitors, 55.1% reported that their positive perception of Japan remained the same, while 22.4% stated that their perception had shifted to a more positive one (Figure 5). Furthermore, 77.9% of those who engage with Japanese popular culture said it improved their perception of Japan (Figure 6). In essence, personal experience of Japan tends to enhance positive views.

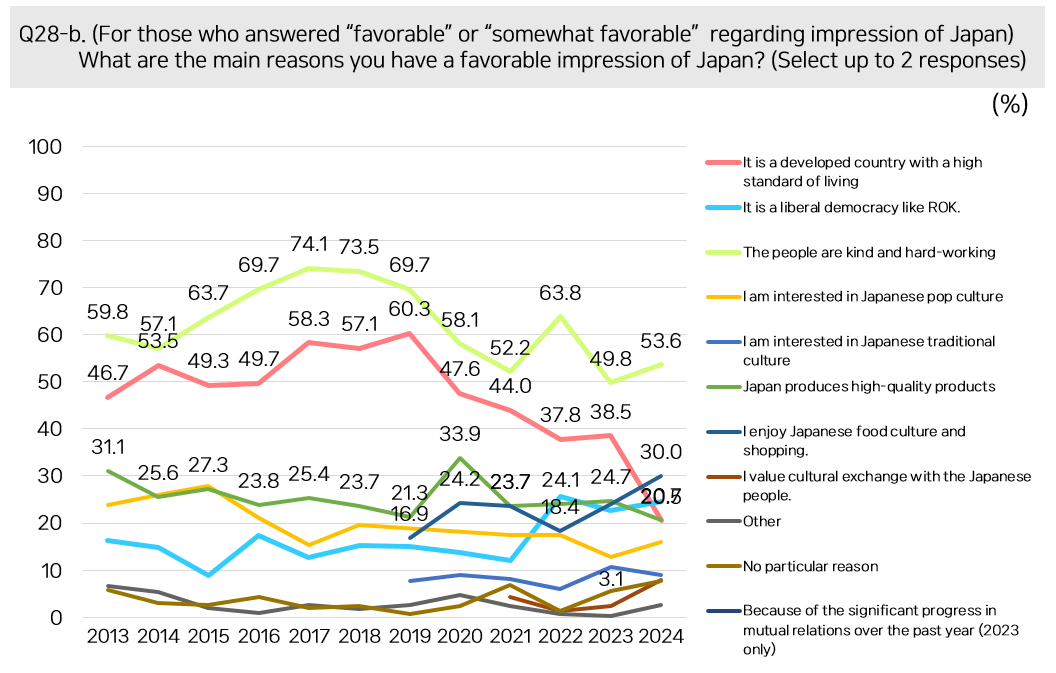

Moreover, as shown in Figure 7, the leading reason for positive feelings toward Japan continues to be its “kind and hardworking people,” followed by “Japanese food culture and shopping” in second place, with “shared values as liberal democracies” rising to third.

Figure 4: Consumption of Japanese Popular Culture

Figure 5: Change in Perception After Visiting Japan

Figure 6: Impact of Popular Culture on Improving Perceptions of Japan

Figure 7: Trends in Reasons for Positive Impressions of Japan (2013-2024)

Overall, the rise in positive perceptions of Japan is partially attributed to the growing sense that South Korea and Japan share security and economic interests. More importantly, however, it is fueled by increased people-to-people exchanges—through popular culture, tourism, and direct interactions—which have enhanced mutual understanding and expanded the sense of shared identity between the two nations. Conversely, the strained ROK-Japan relations over the past 10 years, often dubbed the “Lost Decade,” can be interpreted as the result of “top-down” conflicts among political forces in both nations suppressing the “bottom-up” drive among the people for improving bilateral ties.

Ⅲ. Rise in Criticism of ROK Government’s Japan Policy

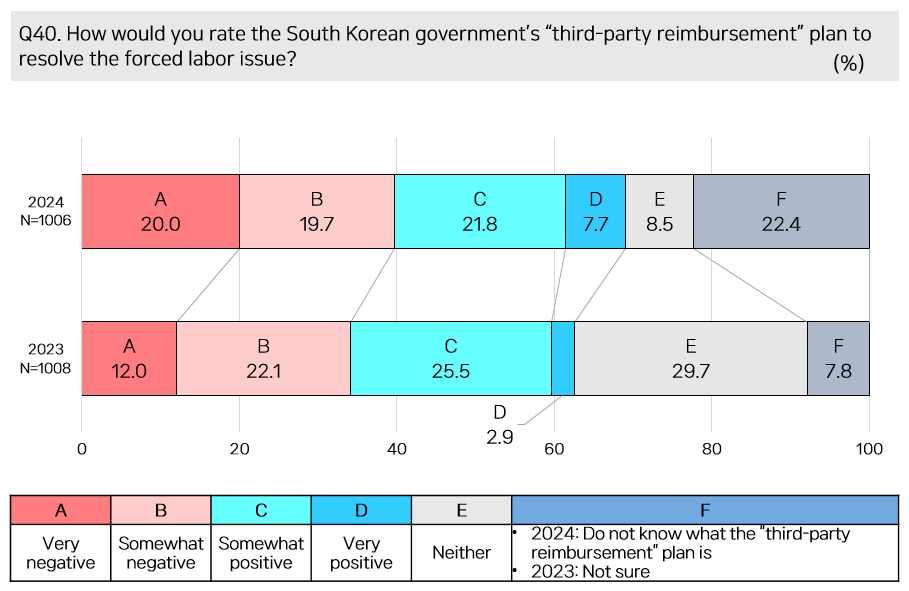

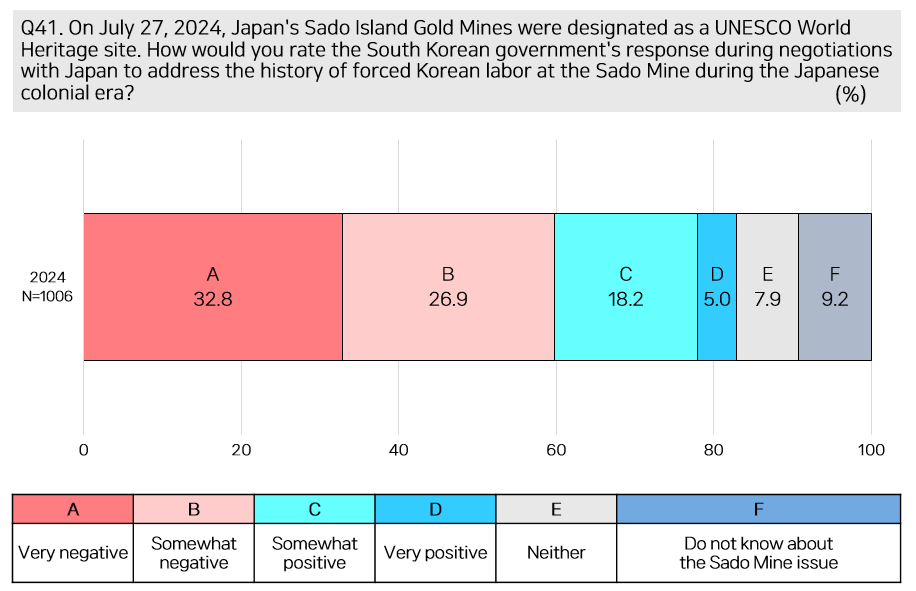

Despite the rise in positive perceptions of Japan and the growing sense of improved bilateral relations, public opinion regarding the South Korean government’s handling of these relations is largely negative. A total of 49.6% of respondents viewed the government’s policy and attitude toward improving ROK-Japan relations unfavorably, compared to 34.5% who assessed it positively (Figure 8). Negative assessments increased by 17.3 percentage points compared to last year. In particular, public discontent far outweighed positive sentiment regarding the “third-party reimbursement” plan for the forced labor issue and the government’s response to the designation of the Sado Island Gold Mines as a UNESCO World Heritage site (Figures 9 and 10).

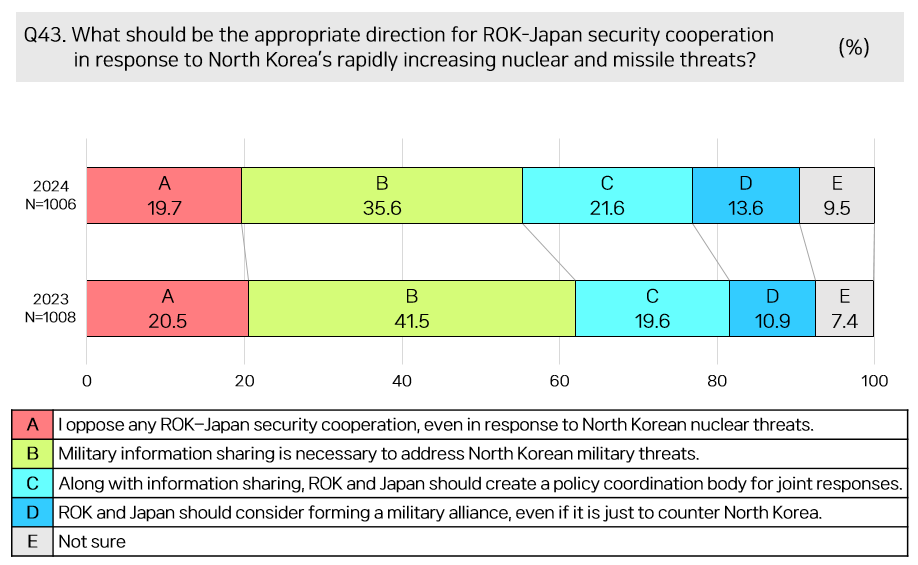

However, public opinion on security cooperation was overwhelmingly positive. A notable 66.5% of respondents supported strengthening trilateral military and security cooperation between South Korea, the U.S., and Japan (Figure 11). Sentiment was also favorable toward bilateral security cooperation with Japan. When asked about the appropriate course for ROK-Japan partnership in response to North Korea’s escalating nuclear and missile threats, 70.8% of respondents indicated that cooperation on information sharing, or beyond, was necessary (Figure 12).

Figure 8: Evaluation of ROK Government’s Attitude Toward Improving ROK-Japan Relations

Figure 9: Evaluation of the “Third-Party Reimbursement” Plan for Forced Labor

Figure 10: Evaluation of ROK Government’s Response to the Designation of Sado Island Gold Mines as a UNESCO World Heritage Site

Figure 11: Opinion on Strengthening ROK-U.S.- Trilateral Cooperation on Military Security

Figure 12: Direction of ROK-Japan Security Cooperation in Response to North Korean Threats

Public evaluation of the Yoon Suk Yeol government’s Japan policy can be summarized as positive regarding efforts to improve relations and foster cooperation in the security sector, but negative in its handling of historical issues. The Yoon government clearly took a proactive approach to breaking the bilateral stalemate by proposing the “third-party reimbursement” plan and holding 12 summits, which significantly contributed to restoring government-level trust. However, the government appears to have relied on an overly optimistic belief that focusing on future-oriented cooperation—particularly in the realm of security, such as ROK-U.S.-Japan cooperation—would eventually lead to the resolution of historical issues as well. This is highlighted by the lack of specific reciprocal measures from Japan following the announcement of the “third-party reimbursement” plan in March 2023, the Yoon government’s lukewarm response to this inaction, and the absence of concrete efforts to address historical disputes, such as the forced labor and comfort women issues.

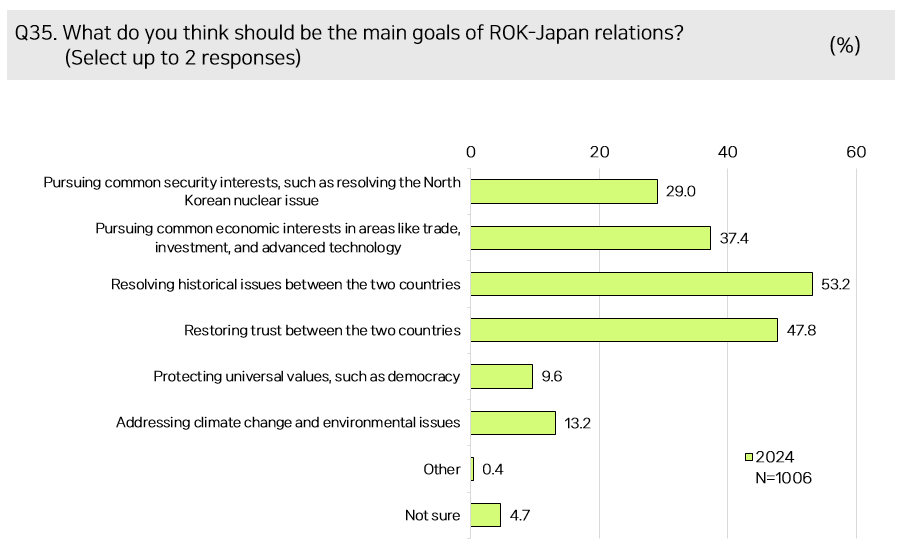

This public opinion survey shows that a majority of South Koreans believe that “a future- oriented cooperative relationship (in areas such as security, economy, culture, and climate change) will be difficult without resolving historical issues” (Figure 13). When asked to identify the top two objectives for ROK-Japan relations, 53.2% selected “resolving historical issues,” while 47.8% chose “restoring bilateral trust” (Figure 14). These results confirm that public perception of the history dispute remains the most critical factor influencing the future direction of ROK-Japan relations.

Figure 13: ROK-Japan Relations and Historical Disputes

Figure 14: Goals for ROK-Japan Relations

Ⅳ. Polarized Perceptions of Japan

The key phenomenon revealed in public opinion on major diplomatic issues is partisan and ideological polarization. On nearly all issues—such as perceptions of Japan, levels of trust, the current government’s Japan policy, and specific policies—supporters of the ruling People Power Party and the conservative bloc gave positive evaluations, while the supporters of the opposition Democratic Party and the progressive bloc gave negative ones. Table 2 in the Appendix clearly illustrates the disparity in opinions between these two groups on various issues. This polarization in South Korean politics is not only dividing public opinion but also hindering the formation of rational policies and affecting the government’s broader foreign policy formulation.

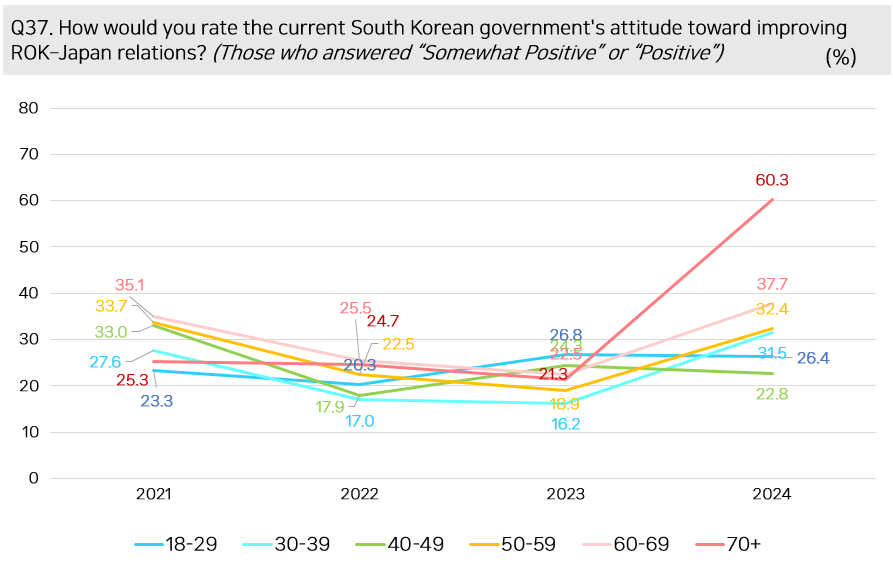

Over the past four years, including a change in presidency, public opinion trends indicate that the gap between conservatives and progressives in their perceptions of Japan has widened since 2023. Conservatives’ evaluations of the South Korean government’s attitude toward improving bilateral relations shifted from negative to positive, while progressives’ assessments shifted from positive to negative (Figures 15 and 16). In other words, support for or opposition to Japan-related issues is becoming increasingly divided along partisan lines.

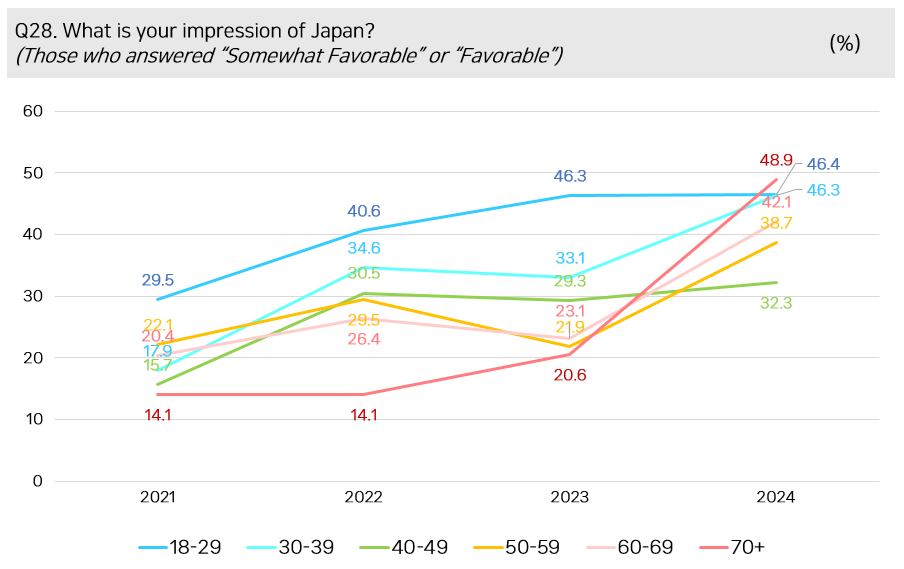

The generational gap is also significant. As discussed in EAI’s ROK-Japan Relations as Seen in Public Opinion 2013-2023 (in Korean), over the past 12 years, younger age groups in their 20s and 30s have been the main drivers of positive perceptions of Japan, while those over 50 and 60 have led negative perceptions. A noteworthy trend in the recent survey is the shift in political attitudes among those in their 60s and 70s. Since 2023, these age groups have developed a more positive perception of Japan, with those in their 70s registering the highest positive impressions among all generations (Figure 17). Similarly, the 70s age group has shown a sharp increase in support for the government’s efforts to improve relations (Figure 18). These changes in the 60s and 70s age groups can be interpreted as a result of partisan alignment with conservative parties. Conversely, the negative attitudes among those in their 40s and 50s can also be understood in terms of their alignment with progressive parties.

In summary, the positive and cooperative attitudes toward Japan revealed in the 2024 survey can be attributed to a combination of the younger generation in their 20s and 30s—who have had direct experiences with Japan through popular culture, tourism, and interpersonal exchanges—and the older generation in their 60s and 70s, who are expressing partisan support.

Figure 15: Positive Perceptions of Japan by Ideological Leaning

Figure 16: Positive Perceptions of ROK Government’s Attitude Toward Improving ROK-Japan Relations by Ideological Leaning

Figure 17: Positive Perceptions of Japan by Age Group

Figure 18: Positive Perceptions of ROK Government’s Attitude Toward Improving ROK-Japan Relations by Age Group

Ⅴ. The Polarization Trap

South Korea is bound to face substantial diplomatic pressure as polarization over Japan policy deepens. First, political forces are prioritizing partisanship over policy rationality. The divisive public opinion reflected in this survey is not driven by individual beliefs or goals, but by the interests and political maneuvering of key leaders. In other words, it is the leaders and political elites who significantly shape public attitudes toward foreign policy. They tend to frame certain foreign policies as polarizing issues, forcing the public into binary choices to weaken their political opponents. A recent example includes last year’s debate over the Fukushima treated water dispute and the Sado Mine controversy, where these issues were framed as “pro-Japan” versus “anti-Japan,” further amplifying public polarization. This trend heightens the risk of extreme voices gaining political influence, while moderate or bipartisan positions are increasingly marginalized.

Second, domestic divisions not only weaken South Korea’s bargaining leverage vis-à-vis Japan, but also hinder the development of a coherent strategy, leading to delays or half-measures in decision-making. Conversely, polarization may prompt the president to bypass opposition from rival parties and unilaterally advance his agendas, relying on unconditional support from his or her constituency. All this undermines democratic accountability.

Third, the ongoing polarization reduces the likelihood of learning from past mistakes in foreign policymaking. Examples include the 2015 comfort women agreement, inaction following the forced labor verdict, and the suspension of the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) extension. In these cases, insufficient efforts to persuade domestic stakeholders, delays in decision-making that triggered diplomatic retaliation, or hardline responses driven by partisan pressure damaged the ROK-U.S. alliance. Instead of using these incidents as lessons to develop a coherent Japan strategy, political leadership tends to focus on partisan justifications.

Fourth, as foreign policy becomes more polarized, disinformation and conspiracy theories proliferate, creating an environment ripe for foreign interference. For instance, false claims that the discharge of Fukushima’s treated water altered the color of the seawater, or baseless accusations that the current government is trying to “erase” Dokdo, have gained traction. The branding of political opponents as pro-Japan “spies” further exacerbates political strife. These developments not only harm South Korea’s soft power but also create opportunities for covert interference from third-party nations.

Last but not least, pursuing policies driven by partisan calculations that exceed the strategic options permitted by the international framework can incur significant costs. For example, the partisan decision to suspend the extension of GSOMIA was blocked by U.S. opposition, which diminished South Korea’s international credibility and ultimately bolstered Japan’s negotiating position.

At a time when geopolitical competition is intensifying and the liberal economic order is in crisis, polarization makes it more difficult for South Korea to effectively address the various structural challenges. It is time to harness wisdom, including pursuing institutional reforms, to ensure that the rational understanding of the ROK-Japan relations held by the majority of South Koreans today is not distorted by partisan polarization. ■

Ⅵ. Appendix

Table 1: Results of Ordinal Logistic Regression Analysis on South Korea’s Perceptions of Japan

|

Variable |

Favorability toward Japan |

Favorability toward Japan |

Favorability toward Japan |

|

Japan visit experience |

1.279*** |

1.250*** |

1.327*** |

|

Degree of engagement with Japanese popular culture |

0.577*** |

0.527*** |

0.499*** |

|

1. Historical Dispute |

|

0.991*** |

0.631*** |

|

2. Historical Dispute |

|

0.525** |

0.455* |

|

North Korean threat |

|

|

0.0755 |

|

Economic relations |

|

|

0.129* |

|

Generation |

|

|

-0.00401 |

|

1.Party |

|

|

0.859*** |

|

2.Party |

|

|

-0.0646 |

|

3.Party |

|

|

0.646* |

|

4.Party |

|

|

-0.0105 |

|

Ideology |

|

|

0.0619 |

|

N |

1,006 |

945 |

669 |

Table 2: Perception of Japan and Policy Views by Party Support

|

|

Total |

Democratic Party Supporters |

People Power Party Supporters |

|

Perception of Japan |

Unfavorable 42.7% |

Unfavorable 55.9% |

Unfavorable 31.4% |

|

Whether Japan is a trustworthy partner |

Distrust 55.1% |

Distrust 71.7% |

Distrust 36.2% |

|

Evaluation of the ROK government’s approach to improving ROK-Japan relations |

Negative 49.6% |

Negative 71.3% |

Negative 20.3% |

|

Evaluation of the “Third-Party Reimbursement” plan |

Negative 39.7% |

Negative 58.5% |

Negative 17.6% |

|

Evaluation of the ROK government’s response to the Sado Mine UNESCO designation |

Negative 59.7% |

Negative 75.4% |

Negative 43.1% |

■ Yul SOHN is the president of EAI and a professor at the Graduate School of International Studies (GSIS) and Underwood International College at Yonsei University.

■ Translated and edited by Jisoo Park, EAI Research Associate

For Inquiries: 02-2277-1683 (ext. 208) jspark@eai.or.kr